Also see People Come First

Centre Pompidou –

5 October, 2022 – 16 January, 2023

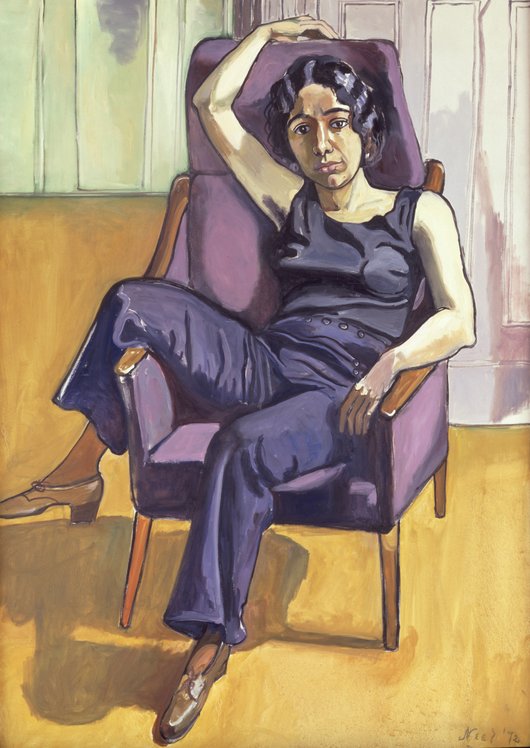

Image: Alice Neel, Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis), 1972

Image: Alice Neel, Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis), 1972

59 3/4 x 42 in

Also see People Come First

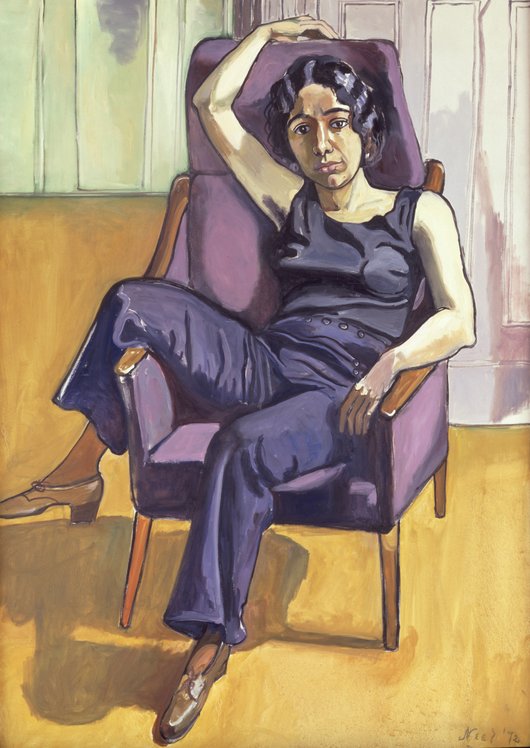

Image: Alice Neel, Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis), 1972

Image: Alice Neel, Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis), 1972

Hammer Museum

October 1 – December 31, 2022

The Hammer Museum at UCLA presents Picasso Cut Papers, an exhibition about an important yet little-known aspect of the practice of Pablo Picasso (1881-1973). This exhibition features some of Pablo Picasso’s most whimsical and intriguing works made on paper and in paper, alongside a select group of sculptures in sheet metal. Cut papers were created as independent works of art, as exploratory pieces in relation to works in other mediums, as models for Picasso’s fabricators, and as gifts or games for family and friends.

Pablo Picasso, Female nude, Barcelona or Paris, 1902–03. Pen and sepia ink on paper pasted onto electric-blue glazed paper. 7 5/8 × 13 5/16 in. (19.3 × 33.8 cm). Museu Picasso, Barcelona. Gift of Pablo Picasso, 1970 © 2022 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York;

Although the artist rarely sold or exhibited them during his lifetime, he signed, dated, and archived them just as he did his works in other mediums. Many examples have been stored flat or disassembled in portfolios until now and will regain their original three-dimensional forms when presented in the exhibition. This survey spans Picasso’s entire career, from his first cut papers, made in 1890, at nine years of age, through the 1960s, with works he made while in his eighties. Picasso Cut Papers will be on view from October 1 to December 31, 2022.

There are approximately 100 works in the exhibition, many of which have never before been displayed in public, with loans coming principally from the Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte, the Picasso estate, and the Musée national Picasso in Paris. Major loans have also been granted by the Museu Picasso in Barcelona; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; and the collection of Gail and Tony Ganz.

“Given our major collection of works on paper from the Renaissance to the present, the Hammer has a long-standing commitment to presenting both historical and contemporary exhibitions of works on paper. We are thrilled to be organizing the first exhibition devoted solely to Pablo Picasso’s inventive cut papers, many of which have never been exhibited. Picasso Cut Papers will also be the first international loan exhibition to occupy our new Works on Paper Gallery.” said Hammer Museum director Ann Philbin.

Picasso played with the versatility of paper and its ability to be folded and molded, attempting to create volume where it is not otherwise perceived. The cut papers embody the artist’s ongoing experiments in breaking down the traditional barriers between drawing, painting, and sculpture, extending into the fields of photography, moving images, and live performance. Picasso Cut Papers is organized loosely chronologically, according to the following sectios:

• Silhouettes • Contours • Cut, Pinned, and Pasted Papers • Torn and Perforated Papers • Shadow Papers • Sculpted Papers • Divertissements • Masks • Diurnes

CREDITS

Picasso Cut Papers is organized by Cynthia Burlingham, deputy director, curatorial affairs, and Allegra Pesenti, independent curator, former associate director and senior curator, Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts. The exhibition is organized with the exceptional support of the Musée national Picasso–Paris.

CATALOGUE

The first publication to focus solely on Picasso’s cut papers, this book features many works reproduced for the first time with newly commissioned photography, alongside new scholarship on a little-known aspect of one of the 20th century’s most pivotal practices. It contributes to the ongoing discourse surrounding innovation and abstraction at the roots of modern art. Also featured is a photo section that surveys Picasso’s engagement with cut paper and sculpture over the decades and documents his practice of cutting paper, both in and out of the studio, with family, friends, and collaborators.

The book features a text by Allegra Pesenti and is edited by Cynthia Burlingham and Pesenti. It is published by DelMonico Books • D.A.P and designed by Miko McGinty and Rita Jules.

That is Linda Stone-Ferrier’s conclusion after analyzing a range of 17th-century Dutch paintings in a new context: that of the neighborhood. Her book, “The Little Street: The Neighborhood in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Art and Culture,” is just out from Yale University Press after a 14-year process of research, writing and editing.

A professor of 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art in KU’s Kress Foundation Department of Art History, Stone-Ferrier realized she would begin research for a book like “The Little Street” when, by chance, she read an article about 17th-century Netherlandish neighborhoods by the sociologist Herman Roodenburg.

“I knew no art historian had ever talked about the neighborhood, which Roodenburg made very clear was a significant organizing unit for social control and social exchange,” Stone-Ferrier said. “No art historians of Dutch art had ever addressed the neighborhood as an interpretive context for the study of Dutch paintings.”

In the book’s introduction, she writes that studies by art historians tend to silo works by subject matter, like landscapes or scenes of daily life, “presum(ing) that each category raises interpretive issues distinct from the others. In a revision of that paradigm, I argue that certain seemingly diverse subjects share the neighborhood as a meaningful context for analysis.”

In addition, Stone-Ferrier writes, her book challenges scholars’ assumptions that categorize “imagery in paintings within a binary construct of ‘private,’ understood as the female domestic sphere, versus ‘public,’ synonymous with the male domain of the city ...”

The neighborhood was a “liminal space” between home and city that encompassed people of every gender, religion, social class, nationality and political persuasion, she writes. In fact, Dutch citizens of the 1600s were required to officially belong to and participate in their neighborhood organizations – much like today’s homes associations – which collected membership dues, enforced neighborhood rules, and hosted mandatory meetings and annual group meals. Thanks to some exquisite recordkeeping from centuries ago and today’s digital resources, Stone-Ferrier was able to research, among other things, relevant subjects of paintings and the identity and professions of Dutch citizenry who owned them that informed her research. Art collecting was important, Stone-Ferrier said, to a broad and deep urban middle class whose wealth was generated by such trading enterprises as the Dutch East and West India companies.

And it's clear, from an analysis of that art and an array of documents, that what was going on down the street and around the corner was important to Dutch people of that time – just as it is to people in neighborhoods around the world today.

“Honor is the word the Dutch used in in their neighborhood regulations and in other contexts, too,” Stone-Ferrier said. “Honor had to do with how one behaved. To act honorably in all endeavors -- personally, at home, in your business -- was valued highly. An individual's honor or dishonor reflected on that of the whole neighborhood. That was an integral tie. That's why there was gossip and documented witness statements regarding the behavior of one’s neighbors.”

One chapter is subtitled “Glimpses, Glances, and Gossip” because — like today -- not only are people curious about what the neighbor across the street is doing in his driveway, or what is going on with those Rottweilers around the corner, but they want to make sure people are not misbehaving or breaking communal rules.

Paintings showing scenes of people upholding neighborhood virtues both reflected and reinforced those values, Stone-Ferrier writes.

On the centenary of its status as the first public museum in the United States to purchase a painting by Vincent van Gogh, the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA) presents a landmark exhibition that tells the story of the artist’s rise to prominence among American audiences. Van Gogh in America features paintings, drawings, and prints by the Dutch Post-Impressionist artist.

The exhibition’s presence in Detroit – and more generally, in the Midwest – holds special significance. The DIA’s 1922 purchase of Self-Portrait (1887) was the first by a public museum in the United States. Notably, the next four Van Gogh paintings purchased by American museums were all in the Midwest, where audiences were galvanized by Van Gogh’s rugged aesthetic, featuring subjects from modern, everyday life; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri; Saint Louis Art Museum; and Toledo Museum of Art. These important purchases – Olive Trees (1889; Kansas City);

Stairway at Auvers (1890; Saint Louis); Houses at Auvers (1890; Toledo); and Wheat Fields with Reaper, Auvers (1890, Toledo) – are all featured in the exhibition.

“One hundred years after the DIA made the bold decision to purchase a Van Gogh painting, we are honored to present Van Gogh in America,” said DIA Director Salvador Salort-Pons. “This unique exhibition includes numerous works that are rarely on public view in the United States, and tells the story – for the first time – of how Van Gogh took shape in the hearts and minds of Americans during the last century.”

One of the most influential artists in the Western canon, Van Gogh amassed a large body of work: more than 850 paintings and almost 1,300 works on paper. He began painting at the age of 27, and was prolific for the next 10 years until his death in 1890.

Works by Van Gogh appeared in more than 50 group shows before he finally received a solo exhibition in an American museum in 1935 at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City. Reflecting and fanning the excitement among American audiences for Van Gogh was Irving Stone’s novel Lust for Life (1934), and Vincente Minnelli’s film adaptation starring Kirk Douglas (1956), which helped shape Americans’ popular understanding of the artist.

“How Van Gogh became a household name in the United States is a fascinating, largely untold story,” said Jill Shaw, Head of the James Pearson Duffy Department of Modern and Contemporary Art and Rebecca A. Boylan and Thomas W. Sidlik Curator of European Art, 1850 –1970, at the DIA. “Van Gogh in America examines the landmark moments and trajectory of the artist becoming fully integrated within the American collective imagination, even though he never set foot in the United States."

The Exhibition

Van Gogh in America is arranged in a narrative fashion spanning 9 galleries, starting with Van Gogh’s Chair (opens in a new tab)(1888; The National Gallery, London):

Starry Night (1888) – on loan from the Musée d'Orsay in Paris – is the newest addition to its Van Gogh in America exhibition, which will run from October 2, 2022 to January 22, 2023 only at the DIA. Featuring more than 70 works by the famed artist, the groundbreaking exhibition is the first ever devoted to Van Gogh’s introduction and early reception in America. Tickets will go on sale this summer.

Starry Night – also known as Starry Night Over the Rhône – is one of two iconic paintings including the nighttime sky that Van Gogh created while living in the French city of Arles from 1888 to 1889. The beloved work captures a clear, star-filled night sky and the reflections of gas lighting over an illuminated Rhône(opens in a new tab) River in Arles with a couple strolling along its banks in the foreground. Starry Night is important to the introduction of Van Gogh’s work to the United States for its pivotal role in the iconic film Lust for Life (1956; directed by Vincente Minnelli). The masterpiece will be on view in the U.S. for the first time since 2011, and is one of three Van Gogh works on loan from the Musée d'Orsay for the DIA exhibition.

Van Gogh in America will be the largest-scale Van Gogh exhibition in America in a generation, featuring paintings, drawings, and prints by Van Gogh from museums and private collections worldwide. Visitors will also “journey” through the defining moments, people, and experiences that catapulted Van Gogh’s work to widespread acclaim in the U.S.

Van Gogh in America reveals the story of how America’s view of Van Gogh’s work evolved during the first half of the 20th century and his rise to cultural prominence in the United States. Despite his work appearing in over 50 group shows during the two decades following his American debut in the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art (commonly known as the Armory Show), it was not until 1935 that Van Gogh was the subject of a solo museum exhibition in the United States. Around the same time, Irving Stone’s novel Lust for Life was published, and its adaptation into film in 1956 shaped and began to solidify America’s popular understanding of Van Gogh.

Major highlights include:

"Two Peasants Digging," 1889, Vincent van Gogh, Dutch; oil on canvas. Stedelijk Musuem, Amsterdam, A411.

Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853–1890). Lullaby:Madame Augustine Roulin Rocking a Cradle (La Berceuse), 1889. Oil on canvas; 36 1/2 x 28 5/8 in. (92.7 x 72.7 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, bequest of John T. Spaulding, 48.548.

Vincent van Gogh

Zundert 1853 – 1890 Auvers-sur-Oise

WALLRAF-RICHARTZ-MUSEUM & FONDATION CORBOUD

The Drawbridge

1888, Oil on canvas, 49.5 x 64.5 cm

Acquired in 1911

Inv. no. WRM 1197

Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

A full-length, illustrated catalogue with essays by Rachel Esner, Joost van der Hoeven, Julia Krikke, Jill Shaw, Susan Alyson Stein, Chris Stolwijk, and Roelie Zwikker, and a chronology by Dorota Chudzicka will accompany the exhibition.

A fascinating exploration of the introduction of Vincent van Gogh’s work to the United States one hundred years later

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890) is one of the most iconic artists in the world, and how he became a household name in the United States is a fascinating, largely untold story. Van Gogh in America details the early reception of the artist’s work by American private collectors, civic institutions, and the general public from the time his work was first exhibited in the United States at the 1913 Armory Show up to his first retrospective in an American museum at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, in 1935, and beyond. The driving force behind this project, the Detroit Institute of Arts, was the very first American public museum to purchase a Van Gogh painting, his Self-Portrait, in 1922, and this publication marks the centenary of that event.

Leading Van Gogh scholars chronicle the considerable efforts made by early promoters of modernism in the United States and Europe, including the Van Gogh family, Helene Kröller-Müller, numerous dealers, collectors, curators, and artists, private and public institutions, and even Hollywood, to frame the artist’s biography and introduce his art to America.