Tuesday, April 3, 2012

Gauguin and Polynesia: An Elusive Paradise

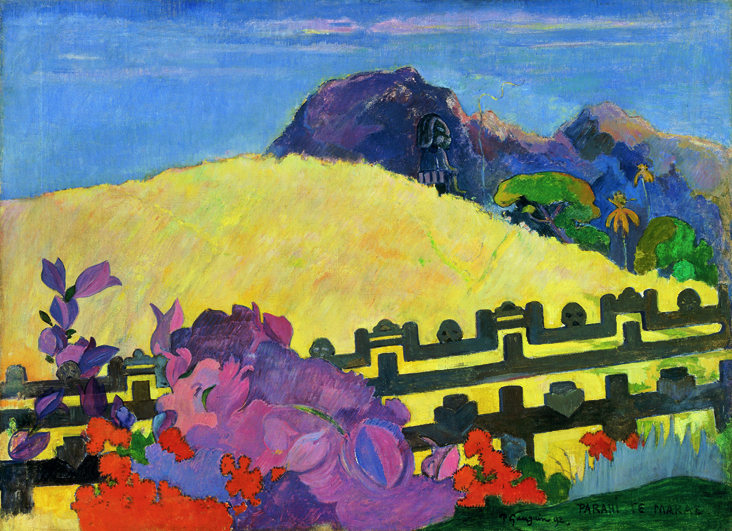

Parahi te Marae (The Sacred Mountain), (1892)

Seattle Art Museum (SAM) presents the only United States stop for Gauguin and Polynesia: An Elusive Paradise, (February 9–April 29, 2012) a landmark show highlighting the complex relationship between Paul Gauguin's work and the art and culture of Polynesia. The exhibition, on view February 9 through April 29, 2012, includes nearly 60 of Gauguin's brilliantly hued paintings, sculptures and works on paper, which are displayed alongside 60 major examples of forceful Polynesian sculpture. Organized by the Art Centre Basel the show is comprised of works on loan from some of the world’s most prestigious museums and private collections.

Recognized for his distinctive palette and the evocative symbolism of his subject matter, Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) is one of the most influential and celebrated artists of the late nineteenth century and was a leader in the Post-Impressionist movement that rejected Impressionism’s emphasis on visual observation. Along with Vincent van Gogh, Emile Bernard and others, Gauguin sought to bring timelessness and poetry into painting. From very early in his career, Gauguin yearned for the exotic in both his life and his work, leading to two significant sojourns in French Polynesia – a two-year stay in Tahiti beginning in 1891 and a second trip to Tahiti, and later, to the even more remote Marquesas Islands, where he would spend the final years of his life searching for the elusive, perfectly primitive life.

Gauguin’s Polynesian experience was a defining factor in both his art and his posthumous reputation, but most exhibitions have treated Polynesian art itself as merely a stylistic tool for the artist. Gauguin and Polynesia aims to contribute not only to a deeper understanding of Gauguin’s work, but also to further an understanding of Polynesian culture. Gauguin and Polynesia traces Gauguin’s journey from bourgeois stockbroker to full-time artist, while at the same time tracing Polynesia’s artistic evolution during the 18th and 19th centuries. Providing a balance of Polynesian art alongside Gauguin’s works, the exhibition offers a solid analysis of how this one artist enacted his own quest for the Polynesian past and reacted to the changes evident in Polynesia during his lifetime. Distinctive sculpture and ornamentation in wood, shell and other natural materials from Tahiti, Easter Island, the Marquesas and elsewhere, will be featured near many of Gauguin’s most iconic canvases including Women of Tahiti (Femmes de Tahiti), 1891; Faaturuma (Melancholic), 1891; Arearea no Varua ino (Words of the Devil, or Reclining Tahitian Women), 1894 and Tehamana Has Many Parents, 1893. Such juxtapositions underscore the complex collision of traditional Polynesian art forms with French colonial pressures, and Gauguin’s distinctly European romanticizing of a simpler and more “natural” way of life.

“The Seattle Art Museum presents its collections in ways that encourage you to look at history while breaking down barriers of time and culture,” said Chiyo Ishikawa, Deputy Director for Art at SAM. “For us, this exhibition provides a wonderful opportunity to continue our mission, fostering a deeper understanding of seemingly disparate cultures through the art that brought them together.”

GAUGUIN’S EARLY YEARS

Paul Gauguin’s biography reveals a complicated personal journey. Born June 7, 1848, to Clovis and Aline Gauguin, the yearning for adventure was likely fueled by an early experience in Peru. In 1849, the Gauguin family left Napoleonic France due to a political climate hostile to the liberal leanings of Gauguin’s journalist-father. En route to Peru, Clovis died of a heart attack, leaving Aline and their two children to complete the journey alone. In Peru, the young Paul Gauguin would have been influenced by both a different natural environment, and by the diverse, upper class Peruvian culture that surrounded him, including relationships with domestic employees from Africa and China.

Returning to France in 1857, Aline Gauguin struggled to support her children, and Paul was eventually enrolled in a prestigious boarding school in Orléans. At the age of 17, the young man joined the merchant marines and, later, the French Navy, in positions that would take him to Brazil, India, the Arctic Circle, the United Kingdom, and many points in between.

He eventually settled into a position as a stockbroker in Paris, where he met and married a young Danish woman named Mette Sophie Gad and had five children in quick succession. Gauguin showed an interest in painting, and collected art in the 1870s, but it was with the collapse of the stock market in 1882 that he decided to pursue his own career as an artist. Mette and the children returned to her native Copenhagen and, apart from a six-month period in which Gauguin joined them there, he established himself as an artist in France.

GAUGUIN’S CAREER IN FRANCE

Gauguin and Polynesia opens with a look at early paintings and sculptures Gauguin created in the late 1880s when he lived in Brittany. Through his life in Brittany and a five-month trip to the Caribbean island of Martinique, Gauguin sought a less costly and simpler lifestyle to fuel his artistic practice. Paintings such asCoastal Landscape from Martinique (1887) and Breton Girl (1889) exemplify the painter’s newfound personal style inspired by these places. Rejecting the Impressionists’ focus on momentary observation, Gauguin sought to impart a decorative timelessness through the “primitive” people and places he encountered both in the Caribbean and in rural France, far from the worries of city life in Paris.

It was during this period that Paul Gauguin developed a short-lived working relationship with Vincent van Gogh which would help define the direction Gauguin’s life and art would take from the 1890s through the end of his life. Gauguin’s involvement in Van Gogh’s Studio of the South – a quixotic attempt to create a rural, artistic community in the town of Arles – led to his own extension of this idea and a desire to found a Studio of the Tropics, even further removed from the bustling European centers and the familiar trappings of modern life.

POLYNESIAN ART IN FRANCE

In 1889, the World’s Fair came to Paris. The Eiffel Tower was erected to show off France’s ingenuity, nationalism and colonial power, and the art and culture of peoples from across the globe were on display. For political reasons, the cultures of the French colonies, including those of French Polynesia, were particularly highlighted.

It is known that Paul Gauguin visited the World’s Fair and encouraged others to do so. References in the artist’s sketchbooks and letters indicate that he returned several times. Gauguin and Polynesia includes a gallery of Polynesian sculptures similar to those that Gauguin would have seen at the World’s Fair. The Moai Kavakava or Cadaverous Male figure, for example, carved of wood and inset with obsidian and bone, represents an evocative art form that had largely disappeared by the time Gauguin reached the South Pacific. The mysterious figure-type, possibly meant to be “inhabited” by an influential ancestor, directly influenced Gauguin’s work, as evidenced in his Christ on the Cross, carved in wood in 1894. Gauguin and Polynesia includes a rubbing made of the sculpture by a friend of Gauguin and published many years after his death.

This brief exposure to the cultures of French Polynesia as well as that of other European colonies, notably Cambodia and Java, provided Gauguin with the final nudge he needed to pursue his idea of creating a Studio of the Tropics, where he and other artists could live and work without the constraints of financial hardship or the formality of life in Western Europe. Very shortly after the Fair, he made several unsuccessful attempts to secure government posts in present-day Vietnam and Madagascar before he successfully received a grant to visit Tahiti, and he left France on April 1, 1891, to “study and paint the customs and landscapes of Tahiti.”

“I’m leaving so that I can be at peace and can rid myself of civilization’s influence. I want to create only simple art. To do that, I need to immerse myself in virgin nature, see only savages, live their life, with no other care than to portray, as would a child, the concepts in my brain using only primitive artistic materials, the only kind that are good and true.” (Paul Gauguin, interviewed before leaving for Tahiti February 23, 1891)

POLYNESIA’S VOLUPTUOUS ARTISTIC PAST; GAUGUIN’S COLONIAL REALITY

By 1500 BC, Polynesian people had begun their epic voyage across the central and eastern Pacific Ocean to settle in what is now known as the Polynesian triangle – a journey that would take European explorers another thousand years to complete. By the time French explorers arrived in the 18th century, Polynesian culture had reached a level of “voluptuousness,” as noted by explorer Antoine-Louis de Bougainville and as evidenced in the works in Gauguin and Polynesia. Polynesian artists developed an evocative aesthetic system which can be seen in patterned wood carvings, ceremonial attire, intricately decorated weapons, and exceptional tattooing. For example, the exhibition includes a Pa’e Kaha from the early- to mid-19th century in the Marquesas Islands. Meant to adorn the head, the most sacred part of the body, this piece includes turtle shell panels that were skillfully curved by wrapping them in leaves and heating them over a fire, and then carved before affixing them to a band of woven coconut palm along with panels of white clam shell. The shallow relief designs mirror those found in Marquesan tikis, petroglyphs and tattoos.

When Paul Gauguin arrived in Papeete, Tahiti in June 1891, he expected to find himself immersed in just such a “voluptuous” culture, a paradise of gentle populations set in nature’s abundance. In fact, what he found was a local culture that had been in decline for more than a century, due to disease, famine, warfare and a prohibition on traditional art forms enforced by the Catholic Church, along with the difficult dealings of a colonial bureaucracy much like that he had left behind in France.

Deeply disappointed at finding so much of what he had sought to escape and so little of the paradise he had expected, Gauguin enacted his own, restless search for Polynesian art, and introduced his imperfect notions of Polynesian religion and culture into the works of art he sent back to Europe. Gauguin and Polynesia balances examples of his interpretation of Tahitian and Marquesan culture with the Polynesian side of the story, presenting art forms that illustrate what he was seeing and providing reflection on what he was not able to comprehend.

Gauguin and Polynesia includes paintings and sculptures that chronicle this search in a number of ways. In some of his earlier, almost documentary paintings, the contrast between the lush beauty of his subject matter and the stark reality of current conditions creates an air of melancholy that is impossible to ignore. For instance, in Vahine no te tiare (Tahitian Woman with a Flower) of 1891, the dignity of the represented woman overwhelms the dowdiness of her prescribed, missionary clothing.

In others, Gauguin co-opts disparate symbols and passages from Polynesian art, combining them in compositions that portray his own imaginings of the culture in which he was living. Arii matamoe (The Royal End), from 1892 is one of the most striking images in the exhibition, portraying the severed head, presumably of a king. The death of Tahiti’s King Pomare V shortly after his arrival in 1891 was incredibly symbolic to Gauguin, indicating to him the death of traditional Polynesian culture. There was, however, no history of such a ritualistic presentation of the king’s head. Rather, Gauguin has created a composition full of Tahitian architectural details and art objects, in which he has re-imagined the biblical scene of the severed head of John the Baptist, a popular theme in late 19th-century France.

The exhibition includes numerous paintings in which Gauguin created the environment he had hoped to find. A motif from a small set of Marquesan ear ornaments, for example becomes a fence keeping viewers from entering a sacred precinct in Parahi te Marae (The Sacred Mountain), (1892), where a tiki is installed on a Tahitian hillside where heightened colors prevail. Gauguin and Polynesia includes specific Polynesian art alongside Gauguin’s unique permutations of their imagery and meaning, allowing a more fully informed investigation of the tension between Gauguin’s representations and the true evolution of the Polynesian cultures in which he lived.