Lyonel Feininger, In a Village Near Paris (Street in Paris, Pink Sky), 1909. Oil on canvas, 39 3/4 x 32 in. (101 x 81.3 cm) University of Iowa Museum of Art, Iowa City; gift of Owen and Leone Elliott 1968.15 © Lyonel Feininger Family, LLC./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

From the University of Iowa Museum of Art:

Cartoon-like characters appear to be hurrying down a village street at dusk in late autumn. Implausible colors and a variety of perspectives define the composition. Lyonel Feininger’s fantastical representation of urban street life seems to capture a moment in time much as a photograph does—it is an embodiment of the distinctive characteristics of modern life.

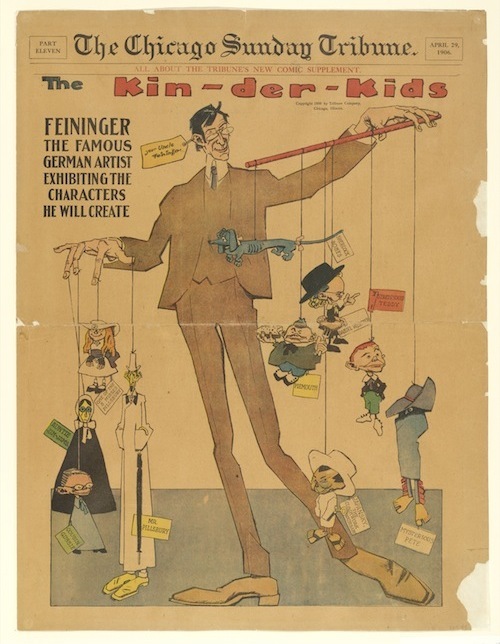

The distorted figures seen in the painting recall Feininger’s 1906–1907 Chicago Tribune comic series The Kin-der-Kids and Wee Willie Winkie’s World. Like his comic characters, the figures in the painting are strangely elongated with small heads on large bodies or squat and rotund, with very little detail on their faces.

Feininger’s multi-vantage point composition and Fauvist color scheme encourages a sensation of ambiguity. Buildings seem tilted and irregular, almost as if they are on the verge of toppling. The scale is reordered—some of the human figures appear more substantial than the buildings—and the color, of the sky in particular, is brash and unnatural. Yet, in spite of the confusing scene, In a Village Near Paris emerges as a vibrant, harmonious, and almost cheerful painting that reflects an advancing modern world.

Lyonel Feininger has long been recognized as a major figure of the Bauhaus, renowned for his romantic, crystalline depictions of architecture and the Baltic Sea. Yet the range and diversity of his achievement are less well known. Lyonel Feininger: At the Edge of the World, the artist’s first retrospective in the United States in forty-five years, is the first ever to incorporate the full breadth of his art by integrating his well-known oils with his political caricatures and pioneering Chicago Sunday Tribune comic strips; his figurative German Expressionist compositions; his architectural photographs of Bauhaus and New York subjects; his miniature hand-carved, painted wooden figures and buildings, known as City at the Edge of the World; and his ethereal late paintings of New York City.

Curated by Barbara Haskell with the assistance of Sasha Nicholas, the exhibition debuted at the Whitney Museum of American Art from June 30 to October 16, 2011, and subsequently traveled to The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, January 16 –May 13, 2012.

Born and raised in New York City, Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956) moved at the age of sixteen to Germany to study music. Instead, he became a caricaturist and eventually a leading member of the German Expressionist groups Die Brücke and Die Blaue Reiter and, later, the Bauhaus. In the late 1930s, when the Nazi campaign against modern art necessitated his return to New York after an absence of fifty years, his marriage of abstraction and recognizable imagery made him a beloved artist in the United States.

Having spent fifty years of his life in Germany, Feininger is most often considered a German artist. This exhibition and its accompanying catalogue illuminate his dual national loyalties and their reverberations in his art. As Haskell notes in her catalogue essay: “(Feininger’s) complex and contradictory allegiances—to American ingenuity and lack of pretension on the one hand, and to German respect for tradition and learning on the other—rendered him an outsider in both countries. Always yearning for one world while living in the other, he never stopped longing for the ‘lost happiness’ of his childhood.”

Before he began to paint in 1907, at the age of thirty-six, Feininger had built a career as one of Germany's most successful caricaturists. When he turned to painting, he fused the whimsical figuration of his comic strips and illustrations with the high-keyed color of German Expressionist painting. Just at the moment that Feininger's oils began to earn him widespread recognition, World War I broke out. He spent the war in Germany as an enemy alien, never having relinquished his American citizenship.

In 1919, Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus, appointed Feininger as the school's first professor and commissioned him to design the cover of the Bauhaus manifesto. Feininger's expressionist woodcut, depicting a tripartite cathedral surrounded by shooting stars, symbolized the school's idealistic unification of fine art, architecture, and crafts.

Feininger remained at the Bauhaus until it was closed by the Nazis in 1933, revered as a teacher and head of the school's graphics workshop. The monumental compositions of architectural and seascape subjects that he produced at the Bauhaus gained him national renown, culminating in his receipt in 1931 of Germany's highest honor for an artist: a large-scale retrospective at Berlin's National Gallery.

When the Nazi Party came to power in 1933, the situation became unbearable for Feininger and his wife, who was Jewish. They moved to America in 1937, just months before his work was featured in the Nazi's infamous Degenerate Art exhibition.

Readjusting to the changed landscape of New York was difficult after such a long absence; not until 1939 did Feininger begin painting again. In America, as in Germany, he employed geometric forms to invest the modern world with a secular spirituality. Art, for him, was a "path to the intangibly Divine,” a way of expressing what he called the “glory there is in Creation." At the same time, Feininger continued in his last years to call upon the playful figurative vocabulary of his early illustrations and comics to evoke the harmony and innocence of childhood.

Feininger's 1944 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, which traveled for two years to major American cities, established him as a major artist in his native country during his final years.

Lyonel Feininger is considered one of the pioneers of modern comic art. His short-lived Chicago Tribune comic strips, The Kin-der-Kids and Wee Willie Winkie’s World, “achieved a breathtaking formal grace unsurpassed in the history of the medium,” as Art Spiegelman noted.

From Huffington Post:

Lyonel Feininger, Carnival in Arcueil, 1911. Oil on canvas, 41 3/10 × 37 8/10 in (104.8 × 95.9 cm). Art Institute of Chicago; Joseph Winterbotham Collection 1990.119, © Lyonel Feininger Family, LLC./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Photograph © The Art Institute of Chicago

..Paintings such as "Carnival in Acrueil," 1914, acquired early on by the Art Institute of Chicago, represent a distinct advancement in Feininger's already proficient caricature technique while showcasing his abilities as a colorist. Centered on an elongated trumpet player, the painting captures a snapshot of a carnival or procession in a small town. The vibrant yellows overshadow the striking linearity of the sky and newly heightened tensions. The tone remains severe in this picture when compared to "Green Bridge," 1909 and others placed in physical conjunction with it.

...As the war began, Feininger embarked on a series of cityscapes focusing on a fairyland of aberrations; worn-down figures in transit, some with facial distortions and others caked in makeup. Feininger's early compositions have an almost stifling effect that leaves the viewer continuously guessing about the circumstances surrounding his actors. Time and motive play a crucial role in an Oatesian fashion almost as if to whisper "where are you going...where have you been?" The pictures function as Pop antecedents, an outgrowth of the comic practice nuanced to a point of differentiation not mere appropriation. Reaching both backwards and forwards, each picture tells a story, a sort of repressed Kentridgesque chronicle in which the tensions and stresses of the current political reality resonate but are simultaneously masked by each figure's anonymity.

In "The Green Bridge II," 1916, Feininger creates a denser, sharper version of his 1909 picture "Green Bridge." Rigid angles and the muted pastel tones vary as analytic cubism begins to play a more prominent role in his work. Still fixated on figuration, this painting remains one of the more pictorially unified of the group. By the end of World War I, Feininger's work had become increasingly abstract with an emphasis on pure color and the "crystalline" structures over genre. Images such as "Bridge V,"1919, a dashing landscape or conflagration of cold grey, yellow, and green, evidence this stylistic alteration in which the artist re-collages a landscape in a Cézannesque fashion yet fills the canvas factoring in negative space as a waste of time and precious canvas. The palette and piercing vectors jutting in every direction collapse into central vortex, dark and impenetrable.

In the late 1920s onto the early 1930s, the Bauhaus' lingering influence in conjunction with his affinity for the Baltic village of Deep altered the compositional structure of Feininger's paintings which appeared to extend off the picture plane. The presence of fog and glimmers of light that drift on and off the canvas play an allegorical role recording the Nazi ascension. The cooler palette of these sparser works captures lonely cityscapes and projections of the sea. The absence of human agents reflects what can only be described as Feininger's longing for stability which he allegedly found, at least in part, when summering in Deep.

What becomes so clear from the exhibition is Feininger's innate ability to assimilate stylistic variations and reassemble them in pictorial form as well as the distinctly German element that pervades his early work on through the First World War. The coarse, sometimes muted colorations of the later, more abstract paintings reveal an increasingly confidence and independence of vision but also express a level of sensitivity and a certain indescribable pain in landscapes void of human actors...

Lyonel Feininger, "The Kin-der-Kids," from The Chicago Sunday Tribune, April 29, 1906, Commercial lithograph, 23 3/8 x 17 13/16 in. (59.4 x 45.3 cm), The Museum of Modern Art, New York; gift of the artist 260.1944.1 © 2011 Lyonel Feininger Family, LLC./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photograph © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Lyonel Feininger, The White Man, 1907, Oil on canvas, 26 7/8 x 20 5/8 in. (68.3 x 52.3 cm), Collection of Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza, © 2011 Lyonel Feininger Family, LLC./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York