In the late 19th century, American artists by the hundreds – including such luminaries as James Abbott McNeill Whistler, John Singer Sargent, Mary Cassatt, Thomas Eakins, and Winslow Homer – were drawn irresistibly to Paris to learn to paint and to establish their reputations. The world's artistic epicenter, Paris inspired decisive changes in American painters' styles and subjects, and stimulated the creation of newly sophisticated art schools and professional standards back in the United States.

At The Metropolitan Museum of Art October 24, 2006–January 28, 2007, the landmark exhibition Americans in Paris, 1860-1900 featured some 100 oil paintings by 37 Americans whose accomplishments proclaim the truth of Henry James's 1887 observation: "It sounds like a paradox, but it is a very simple truth, that when to-day we look for 'American art' we find it mainly in Paris. When we find it out of Paris, we at least find a great deal of Paris in it." Representing the breadth of artistic activity in Paris, the exhibition includes artists who were aligned with vanguard tendencies – particularly Impressionism – as well as those who espoused academic principles. The showing at the Metropolitan Museum was the exhibition's final stop in an international three-city tour.

The exhibition was organized by the National Gallery, London, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in association with The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

"Paris became the world's most beautiful metropolis in the late 19th century, and one of its most dynamic," noted Philippe de Montebello, Director of the Metropolitan Museum. "Filled with the best of the old and the new – from the Louvre's magnificent collections to Haussmann's grand boulevards – the French capital attracted hundreds of American art students and artists, along with their international counterparts. They all found themselves plunged into a vibrant cultural milieu, a city that a Boston painter described as 'one art studio.' Although the lure of Paris for late 19th-century American artists is now widely recognized, Americans in Paris, 1860-1900 breaks new ground as the first-ever treatment of this subject in a major exhibition in leading museums."

Exhibition overview

Picturing Paris

The exhibition began with depictions of popular Parisian sites, from its handsome parks and boulevards to its glittering theatres and cafés. Three scenes portray the elegant Luxembourg Gardens on the Left Bank.

An alluring 1879 canvas by John Singer Sargent (1856-1925)

captures a well-dressed couple on a romantic twilight stroll (Philadelphia Museum of Art).

A panel painting of 1889 by Charles Courtney Curran (1861-1942) focuses on a solitary young woman quietly feeding birds that gather at her feet, while more lively activities take place in the distance (Terra Foundation for American Art).

And women playing with a baby while seated on a bench are the subject of the 1892-94 panel painting by Maurice Brazil Prendergast (1858-1924), a study of texture, pattern, and color (Terra Foundation for American Art).

The audience at a matinee at the Théâtre Français is the focus of the intriguing 1878 canvas

In the Loge (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) by Mary Cassatt (1844-1926).

A fashionable woman peers through opera glasses – at the stage or, perhaps, at the other theatregoers – while a man in a nearby box gazes through his opera glasses at her. Like the pictures of Parisian parks, this image conveys the importance of the city's social spaces in which one could see and be seen.

Artists in Paris

Through more than a dozen portraits, the exhibition introduces some of the painters – American art students and the prominent teachers with whom they studied – who participated in the Parisian art community.

The unconventional 1875 self-portrait of Thomas Hovenden (1840-1895)

shows him every inch the bohemian in his cramped Paris studio, where he slouches, dissolute and disheveled, with a violin in his hand and a cigarette in his mouth, as he stares at a canvas on an easel (Yale University Art Gallery).

In contrast, the bold 1885 self-portrait of Ellen Day Hale (1855-1940)

communicates forthrightness, strength of character, and an independent spirit – in short, the personality traits of a modern young professional woman (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).

In his 1886 portrait of William Walton, James Carroll Beckwith (1852-1917) signals the migration of French styles to America by placing his dapper subject – a former colleague in Paris – against a background of Impressionist landscapes in Beckwith's New York studio (The Century Association).

The influence of James Abbott McNeill Whistler, who was then living in Paris, is evident in the muted tones, thin paint application, and monogrammed signature in the

circa 1896 portrait by Hermann Dudley Murphy (1867-1945) of his fellow student Henry Ossawa Tanner,

who would become the era's foremost African-American artist (The Art Institute of Chicago).

Highly praised when it appeared in the 1879 Paris Salon,

John Singer Sargent's portrait of Carolus-Duran

was painted shortly after the young American had left his renowned teacher's atelier and captures both the master's self-assurance and his famously elegant attire (Sterling and Francine Clark Institute).

The dignified 1898 portrait by Anna Elizabeth Klumpke (1856-1942) of the esteemed animal painter Rosa Bonheur

depicts the elderly artist in the year before her death, seated at the easel, paintbrush in hand, her white hair transformed into a halo by the play of sunlight (The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

At Home in Paris

About one-third of the Americans who studied art in Paris in the late 19th century were women, of whom one of the most distinctive and successful was Mary Cassatt. One of the principal American expatriate painters in Paris and the only American to show with the Impressionists, Cassatt was devoted to recording the world of women like herself. Living in the company of her parents and sister, who moved to Paris in 1877 to be with her, she often portrayed them and their visiting relatives.

Reading Le Figaro (Portrait of a Lady), painted in 1878,

shows Cassatt's mother, who was fluent in French and interested in current affairs, intently reading the French daily newspaper (private collection).

The Tea, painted by Cassatt about 1880,

depicts a young woman in the family's well-appointed Paris apartment playing hostess to a visitor in the daily afternoon ritual (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).

Paris as Proving Ground

Key to the professional ambitions of most late 19th-century American painters, even those who never studied in Paris, was recognition by the Parisian art world. The largest and most prestigious showcases were the annual Salons, immense juried exhibitions organized by the Société des Artistes-Français. In 1863, a separate exhibition – the infamous Salon des Refusés – presented works that had been rejected by the Salon jury. In 1890, a second, less conservative Salon, held under the auspices of the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, was added to the annual calendar. Huge Expositions Universelles, scheduled toward the end of every decade, offered further opportunities to make one's mark, as did displays in commercial art galleries.

The international reputation of James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) for boldness and controversy was launched by his captivating

_1862.jpg/235px-Whistler_James_Symphony_in_White_no_1_(The_White_Girl)_1862.jpg)

Symphony in White, No. 1: The White Girl (National Gallery of Art, Washington), painted in 1862.

The model – who was also Whistler's mistress – stands before a white drapery in a white dress, her long red hair falling loosely, as she holds a white flower in her hand. Rejected by London's Royal Academy in 1862, and then by the 1863 Paris Salon, the enigmatic painting was shown at the Salon des Refusés – where it attracted much notoriety – and in the American section of the 1867 Exposition Universelle.

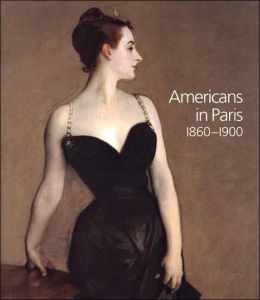

The portraitist John Singer Sargent hoped to garner success by selecting a dazzling subject – the celebrated American beauty Virginie Avegno, who had entered Parisian society by marrying Pierre Gautreau, a wealthy banker. Painted in 1883-84 and shown in the 1884 Salon, the portrait conveys her haughty demeanor as she poses, her head in profile, in a daring black dress. Instead of the hoped-for acclaim,

,_John_Singer_Sargent,_1884_(unfree_frame_crop).jpg/300px-Madame_X_(Madame_Pierre_Gautreau),_John_Singer_Sargent,_1884_(unfree_frame_crop).jpg)

Madame X (Madame Pierre Gautreau)

created a scandal that effectively ended Sargent's career in Paris. He moved to London in 1886, and made it his headquarters for the rest of his life. The painting – which he considered to be his best work – remained in his possession until 1916, when he sold it to the Metropolitan Museum.

Rural Retreats in France

Although they had been drawn to Paris by its schools, museums, and exhibitions, artists almost always fled the city in summer, seeking relief from summer heat and respite from professional pressures. Traveling by railroad, then by horse-drawn carriage, and finally, sometimes, on foot, they sought out rural retreats – usually not too distant from the capital. Such places offered opportunities for camaraderie, picturesque subjects, and vestiges of earlier, simpler times, as well as cheap accommodations and modest living costs. While some painters spent time in several of the art colonies that flourished during the period – Barbizon, Pont-Aven, and Grez-sur-Loing, for example – others visited only one, and a few even purchased homes in hospitable locales, built studios, and remained for years.

John Singer Sargent and Claude Monet were lifelong friends. In 1885, the year after the failure of Madame X in the Salon, Sargent visited the Norman village of Giverny, where Monet had been living for two years. There the American created his

Claude Monet Painting by the Edge of a Wood (Tate, London),

which shows the French master immersed in nature, working en plein air. An important art colony, populated mainly by Americans, would begin to develop in Giverny by 1887.

Emerging from this community of artists was Theodore Robinson (1852-1896), one of the very few Americans from Giverny's art colony with whom Monet became friendly. Robinson painted his unique canvas,

The Wedding March (Terra Foundation for American Art),

in 1892 to commemorate the marriage of American painter Theodore Butler to Monet's stepdaughter in Giverny, a union that Monet opposed.

Childe Hassam (1859-1935) depicted another bucolic site in 1888 in his painting Geraniums (The Hyde Collection).

The setting is the garden at the home of friends in Villiers-le-Bel, just north of Paris. Hassam's wife can be seen through the open window, partially obscured by blossoms, as she tends to her sewing.

Rural Retreats in the United States

When American artists returned home, they sought out rural retreats that resembled those they had frequented in Europe. These places, which were often in New England, provided a welcome change from modern urban life, connection with old-fashioned values, and opportunities for outdoor painting. The vivid 1888 canvas

Chrysanthemums (Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum) by Dennis Miller Bunker (1861-1890) –

among the first Impressionist canvases made in the United States – shows the riotous floral display in the greenhouse at Green Hill, the Massachusetts summer home of the art patrons John L. and Isabella Stewart Gardner.

Three Sisters – A Study in June Sunlight (Milwaukee Art Museum), painted in 1890 by Edmund Charles Tarbell (1862-1938),

was the artist's first important work in the Impressionist style. The artist's wife (holding her daughter) and her sisters sit in a sun-dappled New England garden, probably in Dorchester, a historic village that had been annexed recently to Boston.

Catalogue and Related Programs

The exhibition was accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue. It was written by the exhibition's curators Kathleen Adler (Director of Education, National Gallery, London), Erica E. Hirshler (Croll Senior Curator of Paintings, Art of the Americas, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), and H. Barbara Weinberg (Alice Pratt Brown Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture, The Metropolitan Museum of Art), with contributions from David Park Curry, Rodolphe Rapetti, and Christopher Riopelle, and with the assistance of Megan Holloway Fort and Kathleen Mrachek. The book was published by the National Gallery Company.

The exhibition was organized at the Metropolitan Museum by H. Barbara Weinberg, the Alice Pratt Brown Curator of American Paintings and Sculpture, with assistance from Elizabeth Athens, Research Assistant.