Political, economic, and social turmoil shaped Germany's short-lived Weimar Republic (1919–1933). These pivotal years also became a most creative period of 20th-century German culture, generating innovation in literature, music, film, theater, and architecture. In painting, a trend of matter-of-fact realism took hold in Germany like nowhere else in Europe. Disillusioned by the cataclysm of World War I, the most vital German artists moved towards a Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), in particular its branch known as Verism. These artists looked soberly, cynically, and even ferociously at their fellow citizens and found their true métier in portraiture, as seen in the 40 paintings and 60 works on paper featured in Glitter and Doom: German Portraits from the 1920s, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, November 14, 2006 – February 19, 2007, included gripping portraits by ten renowned artists: Max Beckmann, Heinrich Maria Davringhausen, Otto Dix, George Grosz, Karl Hubbuch, Ludwig Meidner, Christian Schad, Rudolf Schlichter, Georg Scholz, and Gert H. Wollheim.

This landmark presentation was the first anywhere to focus on the portraiture of the Weimar period. In these gripping images, the rootless society that flourished or floundered during these years in metropolises such as Berlin, Düsseldorf, and Dresden jolts back to life.

Although memorialized in song and story for the escapist thrills of erotic cabaret shows, wild dancing, frenzied jazz, and sexual licentiousness, German cities of the 1920s were in the throes of rampant unemployment, hyperinflation, and social panic. After the initial patriotic fervor, followed by the crippling devastation of World War I, the Verists questioned their own involvement in this war and focused on the country's quickly changing social landscape and uncertain political future.

Forgoing new modes of abstraction, the artists found worthy subjects in urban denizens of all walks of life, from the war wounded to the art dealer. With a marked abhorrence of idealization, the Verists' portraits captured the stark existence of a populace through an incisive and often satiric form of realism. Their psychological portraits do not attempt to reproduce likenesses, as in the conservative painting styles popular at the time. Rather, with savage distortions of the face and the figure, the artist turns the sitter into an exaggerated type that reflects the extremes of a turbulent era: wealth and poverty, glamour and violence, decadence and banality.

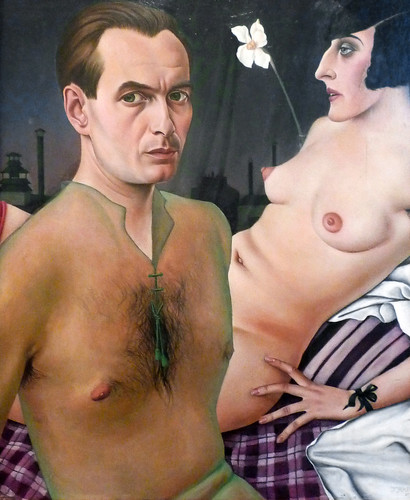

People of vastly different backgrounds came together in the common pursuit of pleasure as Germany's traditional class structure and moral strictures collapsed. Christian Schad's portraits depict the modern individual caught between debauchery and ennui. In

Count St. Genois d'Anneaucourt (1927),

Schad places the jaded and aging Count between the cold profile of a mannish woman and the willowy figure of her rival, a transvestite.

Many of the artists suffered from the lingering trauma of the war, and their portraits convey a pervasive malaise.

In Max Beckmann's Dance in Baden-Baden (1923),

stylishly dressed couples go through the motions of living the high life, their expressions indifferent and weary. Even the artists themselves seem be to role-playing, as seen in Beckmann's forced pose as a bon vivant in

Self-Portrait with Champagne Glass (1919).

Social criticism also took more pointedly political forms, when artists filled with anger and distrust satirized corrupt individuals in scathing portraits.

George Grosz's The Pillars of Society (1926)

mocks politicians, military men, and priests, who grit their teeth and puff their cheeks while violence and destruction loom in the background.

The exhibition also featured

Grosz's large painting Eclipse of the Sun (1926),

which was on extended loan from the Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington, New York. In this major work, Grosz attacks the incompetence and weakness of German political leaders and foretells of the demise of the Weimar Republic.

Although their subjects were purely contemporary, artists such as Otto Dix and Christian Schad were inspired by 16th-century German masters, such as Cranach, Dürer, Holbein, and Grünewald. Otto Dix adhered most closely to their painting techniques, while exploring the particular vices of the Weimar era. Dix sought out a brutal truth by looking unflinchingly at the most grotesque, violent, and debased aspects of society. Typical of his subject matter is

The Salon I(1921),

which portrays four elderly prostitutes in cheap finery that fails to hide their decrepitude.

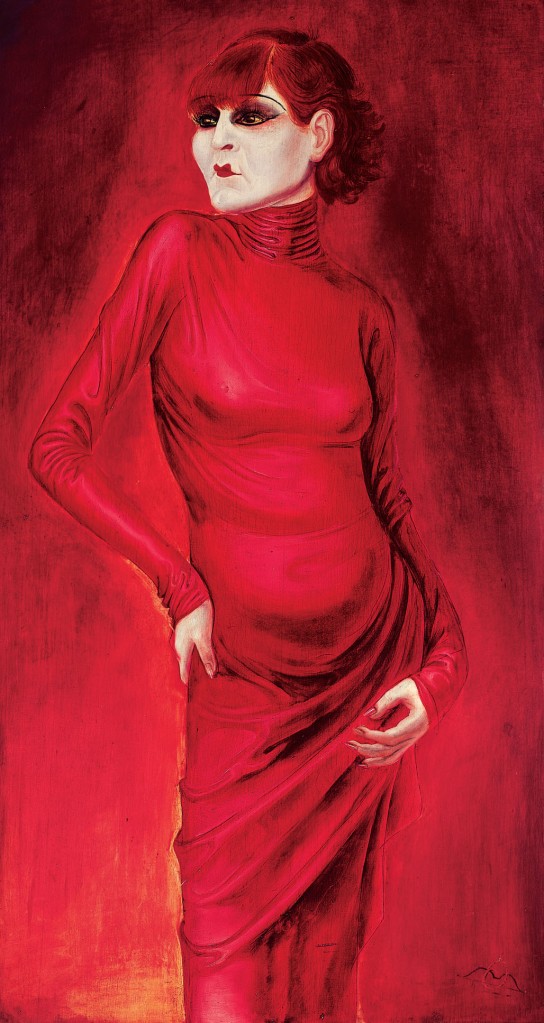

Dix's 1925 portrait of Anita Berber

immortalizes the infamous dancer, nude performer, actress, seductress of men and women, and cocaine addict, who, in her brief career (1916-28), distilled the excesses, glamour, and misery of the Weimar Republic. With more than 50 works by Otto Dix, this exhibition was the first major presentation of the artist's work in the U.S.

With harsh candor and biting humor, the portraits in the exhibition dissect a Weimar demimonde of prostitutes and profiteers, war veterans and war widows, performers and poets. The Verists themselves were part of this shattered world, mingling in the crowd with former aristocrats, middle-class doctors, and businessmen. Their powerful images serve as mirrors to a glittering yet doomed society. With Hitler's rise to power in 1933 and the end of the Weimar Republic, artists lost their teaching positions, their work was banned, and many of them went into exile.

German museum collections in Berlin, Cologne, Dresden, Düsseldorf, Hamburg, Frankfurt am Main, Mannheim, Münich, Stuttgart, and Wuppertal lent works to the exhibition. Additional portraits will be on loan from museums in Paris, Madrid, New York, and Toronto, as well as from private collections in Germany, Australia, New York, and Chicago.

The exhibition was organized by Sabine Rewald, Jacques and Natasha Gelman Curator in the Department of Nineteenth-Century, Modern, and Contemporary Art.

She is also the author of the exhibition catalogue, published by the Metropolitan Museum and distributed by Yale University Press. The publication includes essays by Ian Buruma and Matthias Eberle.

From an outstanding review (images added):

In the past two months I've returned a dozen times, on each occasion seeing something completely different: the heady influence of cabaret; of wacky doctors and modern medicine; of Neue Sachlichkeit and the tortuous realism of the Weimar Republic; and numerous other influences from the magic Realists to the demi-monde of prostitutes and their johns. Here sleek elegance meets tattered old whores, and scads of twisted and contorted figures underscore so much of the depravity and grotesqueness of the era. Early this morning, for example, I encountered a guard staring transfixed at George Grosz's "Pillars of Society" (1926); she offered the most prescient comment before the exhibition rooms began to fill up: "At first, it wasn't so crowded, but word of mouth spread like wildfire." And indeed, within 30 minutes once again the galleries were packed, with patrons examining the hideous figures, ominous scenes, and deeply insightful views on war.

As with his "The Eclipse of the Sun" (1926, on loan from the Heckscher Museum in Huntington), Grosz deftly attacks the inept Hindenburg government, making no secret of his obvious detestation of the evil forces at work in Weimar society. Hideous, twisted veterans figure in various paintings, less prominently in

Grosz's "Gray Day" (1921)

than in Dix's utterly wrecked "Skat Players" (1920, photo above).

With their nearly-innumerable prosthetic devices, one figure holds cards with a foot, another holds a card in his teeth.

Otto Dix's portraiture is also unforgiving of the aging figures of Berlin.

Poet Iwar von Lücken (1926)

is depicted in rumpled and shabby clothes, with huge, rake-like hands, a head with huge, bulging veins, craggy face and sunken eyes. Poor von Lücken starved in Paris during the first winter of World War II.

Sadness seems transformed into rapaciousness in Dix's portrait of the art dealer

Alfred Flechtheim (1926),

whose enormous and similarly rake-like hands suggest the money-grubbing inherent to his art business; in addition to the enormous nose, tweed suit and Cubist (i.e. dated) painting on the wall, all the elements crudely and succinctly reduce Flechtheim to the archetypical greedy Jew.

Dix had two years earlier painted the art dealer

Johanna Ey,

whose unflattering portrait features this enormous, full-bodied figure in a fur-trimmed purple dress, here appearing almost aristocratic with a tiara, ruby earrings, huge eyes and elongated chubby face.

Rotundness also figures in a painting of

Dr. Mayer-Hermann (1926),

where the portly doctor's bulbousness seems magnified by the all cylindrical objects surrounding him.

Dix's portrait of

Dr. Heinrich Stadelmann (1922),

meanwhile, reduces this patron of Dada to a possessed freak with Svengali-like, hypnotic eyes. In a sharp suit with flowing hair and a greenish-grayish face, the clenched hands of Stadelmann lend an additional otherworldly if not demonic demeanor.

Twisted and contorted hands also figure prominently in Dix's cruel portrait of the

Jeweler Karl Krall (1923),

where vibrant tones highlight this dandy with a birdlike chest, standing in an effeminate pose, with reddish-gray cherubic face and hands splayed suggestively on his hips. Little wonder Krall quickly gave the portrait to the Nationalgalerie in Berlin!

Manicured and lacquered claws also figure prominently in paintings of females; Dix paints Anita Berber (1925) as rather spent from years of drug use—she died three years later—in a wild red dress, tightly shaped around her otherwise supple body. Though the paunch of this aging starlet is obvious, her face is haunting, with pursed red lips, green eyes, outlandish mascara, thin penciled-in eyebrows and wild red hair. All these reds—as with Krall—seem additionally vampirish against the red background. Stated differently, the lady is a vamp?

Similarly, Grosz's portraits are no less haunting:

Max Herrmann-Neisse (1925)

depicts the writer as wrinkled, with sagging features, an enormous skull, sunken eyes and huge protruding veins.

A somewhat more gentle and less dramatic version from 1927

hangs inconspicuously in the rather hidden third-floor staircase at the Museum of Modern Art. The latter portrait nevertheless still depicts a grotesque and veiny skull, though sans enormous ruby ring that figures so prominently in the Mannheim painting.

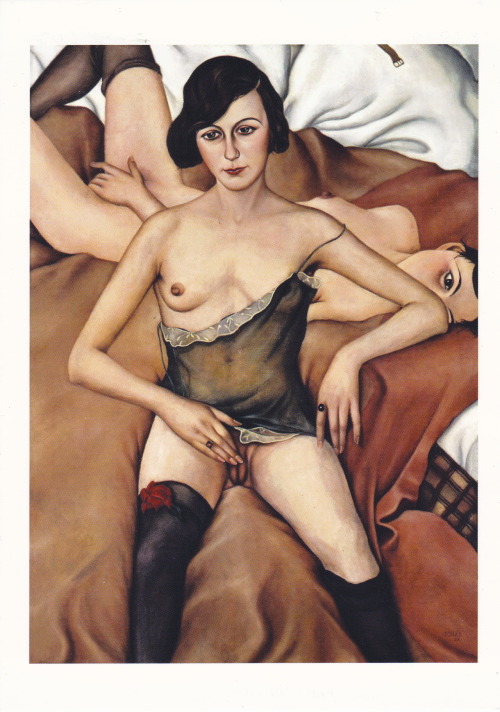

There is no shortage of hideousness in the Weimar depiction of women, ranging from youngish whores to elderly whores. Dix's The Salon 1 (1921) prominently portrays one aging prostitute squeezing her right breast while the other three seated together at the table stare off into space. The wallpaper, drapery and white lace contrast sharply with these chalk-colored painted ladies. Indeed one could probably write a doctoral thesis comparing the milieu of this painting with that of Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon fifteen years earlier.

Christian Schad's "Two Girls" (1928) features a rather lush masturbation scene;

his "Agosta, the Pigeon-Chested Man, and Rasha, the Black Dove" (1929) offers the contrasting sideshow freaks of a busty black woman at front and the hideously deformed Agosta at rear;

and heady sexuality impregnate both "Baroness Vera Wassilko" (1926)

and "Count St. Genois d'Anneaucourt" (1927).

Do additionally inspect the female hands as portrayed in

"The Old Actress" (1926) by Max Beckmann

plus his portrait of Fridel Battenberg (1920).

Then perhaps contrast these females with the wild decadence seen in Beckmann's "Self Portrait with Champagne Glass" (1919)

and Dix's "To Beauty" (1922),

wherein Dix poses next to a wild-looking black jazz musician. (Note Dix's clenched left fist on the telephone, right hand in pocket.)

Coupled with Schad's dreamlike and hypersexual

"Self-Portrait" (1927),

it seems the artists' self-indulgence or wallowing in whoring allows them to depict these women as their accessories in a slightly more flattering milieu. Nevertheless, all three self-portraits show deeply conflicting emotions, the pain simultaneously felt with pleasure.

More images:

%20by%20Max%20Beckmann.jpg)