Daumier (1808-1879): Visions of Paris at the Royal Academy, London, to Jan 26; will be the first major exhibition of the prolific artist and social commentator, Honoré Daumier, to be held in Britain for over fifty years. Admired by the avantgarde circles of 19th century France and described by Baudelaire as one of the most important men ‘in the whole of modern art,’ the exhibition will explore Daumier’s legacy through 130 works, many of which have never been seen in the UK before, with a concentration on paintings, drawings, watercolours and sculptures.

Daumier lived and worked through widespread political and social change in France during his lifetime, which encompassed the upheavals of the revolutions to establish a republic, in the face of continued support for the monarchy.

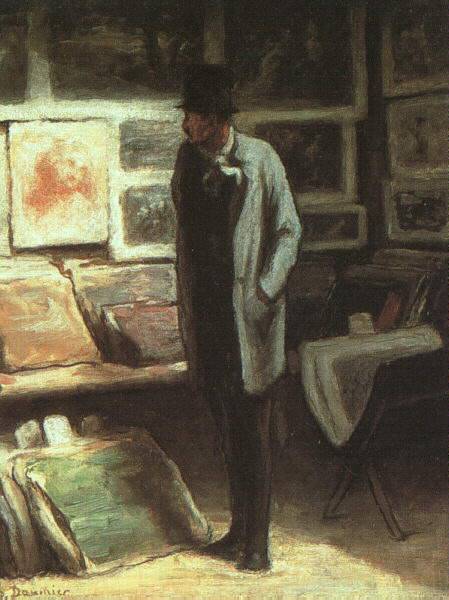

Daumier (1808-1879): Visions of Paris will be displayed chronologically, spanning the breadth and variety of his often experimental artistic output and exploring themes of judgement, spectatorship and reverie. One of Daumier’s favourite subjects became the silent contemplation of art, as seen in

The Print Collector, 1857-63 (The Art Institute of Chicago)

and in the terrified performer alone on the stage in What A Frightful Spectacle c.1865 (Private Collection).

Daumier’s extraordinary visual memory allowed him to recall and portray many facets of everyday life in both sympathetic and critical observations.

Daumier (1808-1879): Visions of Paris will exhibit works depicting his working class neighbours on the Quai d’Anjou on the Ile Saint-Louis, as well as topical issues such as fugitives of the cholera epidemics or the experience of travellers in

A Third Class Carriage, 1862-64 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York).

Daumier also drew parallels between the abuse of power by lawyers in

The Defence, c. 1865 (The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London)

and the silent vulnerability of those on the margin in

Clown Playing A Drum, 1865-7 (British Museum, London).

A staunch Republican, Daumier was particularly renowned for his daring and uncompromising caricatures of the manners and pretensions of his era, including the corruption of the government of Louis-Philippe, the King of France from 1830-1848. Drawn with an unforgettable energy and expressiveness, the majority of these works were published as lithographs in newspapers. At the end of Daumier’s life he created scenes and allegories of the link between nationalism and military action: the ideal female figures of France and Liberty, contrasted with the jester or Don Quixote, two characters Daumier closely identified with.

Daumier believed artists should ‘be of their times’, and his work drew praise from his contemporaries Delacroix and Corot, and those of the next generation, Degas, Cézanne and Van Gogh.

BIOGRAPHY

Honoré Daumier was born in 1808 to a working class parents in Marseilles. In 1815 the family joined his father, by now an aspiring writer, in Paris, where Daumier began work as a bailiff’s assistant and bookkeeper’s clerk. Daumier received little formal artistic training as a painter. In 1822 he briefly took lessons with father’s friend, the artist Alexander Lenoir and met other painters and sculptors at the Academy Suisse and Academy Boudin where he attended untutored life drawing classes during the 1820s. In 1825 he was apprenticed to Zepherin Belliard, a specialist in lithographic portraiture.

The start of Daumier’s career as a press caricaturist coincided with a freedom of press law in 1830, but by 1832 Daumier found himself imprisoned for his uncompromising lithographs of King Louis- Philippe and his government. Over the course of forty years, he contributed on a weekly basis to the satirical journals edited by Charles Philipon, La Caricature and Le Charivari. Daumier became famous for his humorous caricatures of subjects political and - during times of strict censorship – social.

Daumier made a memorable group of small sculpted busts as models for caricatures in the mid- 1830s and began painting in the 1840s. In 1846 Daumier married the seamstress Marie-Alexandrine Dassy and they lived in the Quai d’Anjou, where they remained until c.1861. Neighbours included Charles Baudelaire, Théophile Gautier and artists who were good friends, such as Camille Corot and Adolphe-Victor Geoffroy-Dechaume. He exhibited paintings in the Salons of 1849 and 1850/51, however, his work as a fine artist was shown very little in his lifetime and he was perpetually in debt.

In 1870 Daumier was nominated for the Légion d’honneur, which he declined to accept. Daumier died, nearly blind, at his house in Valmondois, in the Ile-de-France region on February 10, 1879. His total output of 4000 lithographs, 1000 drawings for woodcuts and a remarkable body of paintings, drawings and watercolours, has been continually reappraised since his death, most especially by artists.

ORGANISATION

Daumier (1808-1879): Visions of Paris has been organised by the Royal Academy of Arts, London. The exhibition has been curated by Catherine Lampert, independent Curator and Art Historian with Ann Dumas, Curator, Royal Academy of Arts.

CATALOGUE

The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue, with contributions from Catherine Lampert, Michael Pantazzi, T.J. Clark, John Berger and others.

From a review in The Guardian (and see links to more images):

Daumier barely survived as the greatest cartoonist of his age – hired, fired, censored, atrociously underpaid; he never thought to sell his sculptures and painted almost as a private experiment. This gives a freedom to his pictures that cannot be found among many of his contemporaries.

Take Man on a Rope, in which the eponymous man dangles in thin air, neither up nor down, with no context to limit the freedom. The figure – high energy embodied in a form unqualified by anything so distracting as face or hair – is like Spider-Man contained in his outline. And the picture has been scraped, gouged, scratched and generally assaulted like some Anselm Kiefer canvas. Nobody seeing it in the Royal Academy could fail to be startled.

Man on a Rope, c.1858: ‘the eponymous man dangles in thin air, neither up nor down, with no context to limit the freedom’. Photograph: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Tompkins Collection - Arthur Gordon Tompkins Fund

Most moving of all are the mother and child to whom Daumier returns over and again, each time with increasing empathy. She is a laundress with a terrible load, pressing on through life and labour. The child holds on to the woman, the woman struggles to hold up the immense burden of her laundry, while clearly talking to the child, day after day and into the long night. It would be impossible to overstate the mounting pathos of these works.

The Laundress, 1861-63. Photograph: © The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

Daumier is a master of light and dark. There are patches of pure light – a lit stage, a distant window, a glowing doorway to freedom – and obliterating darkness. Don Quixote has become fused with his own horse: a dark giant wandering through the blackest hell. A man lugging a sack on to a boat is Sisyphus on a gangplank in the fog. These figures pass into the proverbial, but they always retain their own personalities no matter how close to archetype.

More images from the exhibition:

Honoré Daumier, Lunch in the Country, c. 1867-1868, Oil on panel, 26 x 34 cm, National Museum of Wales, Cardiff, Photo © National Museum of Wales

Honoré Daumier, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, c. 1855, Oil on oak, 40.3 x 64.1 cm, The National Gallery, London. Sir Hugh Lane Bequest, 1917

Another excellent review with links to images.