Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Madison, WI January 25, 2014 to April 27, 2014.

Real/Surreal is a circulating loan exhibition organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. The exhibition explores the interconnections between the real and the imagined in early modern American art, with an emphasis on Surrealism and Magic Realism. The exhibition includes paintings, drawings, and prints by Thomas Hart Benton, Charles Burchfield, Paul Cadmus, Philip Evergood, Jared French, Marsden Hartley, Edward Hopper, Man Ray, Charles Sheeler, George Tooker, John Wilde, and Grant Wood among others. MMoCA has added works from its own permanent collection, including a major watercolor by Andrew Wyeth and a significant painting by Marsden Hartley.

George Tooker, The Subway, 1950. Egg tempera on composition board, 18½ x 36½ inches. Collection of Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Juliana Force Purchase Award.

Edward Hopper, Cape Cod Sunset, 1934. Oil on canvas, 29 1⁄8 x 36 ¼ inches. Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Josephine N. Hopper Bequest 70.1166. © Heirs of Josephine N. Hopper, Licensed by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Andrew Wyeth, "Winter Fields", 1942. Tempera, oil, ink, and gesso on composition board, 175/16 × 41 inches. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Benno C. Schmidt in memory of Mr. Josiah Marvel, first owner of this picture 77.91 © Andrew Wyeth.

Jared French, State Park, 1946. Tempera on composition board, 247/16 x 24½. inches. Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. R. H. Donnelley Erdman 65.78. Photography by Sheldan C. Collins.

Federico Castellón, The Dark Figure, 1938. Oil on canvas, 17 3/8 x 26 ¼ inches. Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Purchase 42.3. Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, NY. Photography by Sheldan C. Collins.

Henry Koerner, Mirror of Life, 1946. Oil on composition board, 36 x 42 inches. Collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Purchase 48.2. Courtesy of Joseph and Joan Koerner. Digital Image © Whitney Museum of American Art.

Man Ray (1890–1976), La Fortune, 1938. Oil on canvas, 24 × 29 in. (61 × 73.7 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase with funds from the Simon Foundation Inc. 72.129. © 2009 Man Ray Trust / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris

From a NY Times Review (images added):

Edward Hopper’s “Early Sunday Morning” (1930), his famous picture of storefronts bathed in sunlight, captures an experience of urban life with uncanny vividness. Yet a mood of aching loneliness and suspenseful mystery tilts it toward Surrealism. The Italian visionary Giorgio de Chirico may come to mind, as he does in the instances of

George Ault’s “Hudson Street” (1932),

a haunting view of an eerily quiet Manhattan industrial area, and of

Francis Criss’s “Astor Place” (1932),

in which two nuns enveloped in black habits ominously converse on a corner of a deserted city square. Notice the nearby sign (which says) : “Keep Right.”George Tooker’s “Subway” (1950) shifts the balance further toward surreal dream. An anxious woman in a red dress pauses in an underground corridor with suspicious-looking men in long coats lurking in the background. But Tooker’s careful rendering of New York’s subterranean architecture grounds the nightmare firmly in a familiar, concrete reality...While there is little here in the vein of Social Realist protest, disaffection from the mainstream of American life prevails.

Joe Jones’s “American Farm” (1936), a distant view of farm buildings on a high plateau surrounded by a deathly landscape of earth eroded into deep gullies and ravines, alludes overtly to the Dust Bowl, which added ecological insult to the injuries of the Great Depression. But it also conveys feelings of isolation and despair whose roots extended to a psychic geography reaching far beyond the borders of the so-called American Breadbasket...

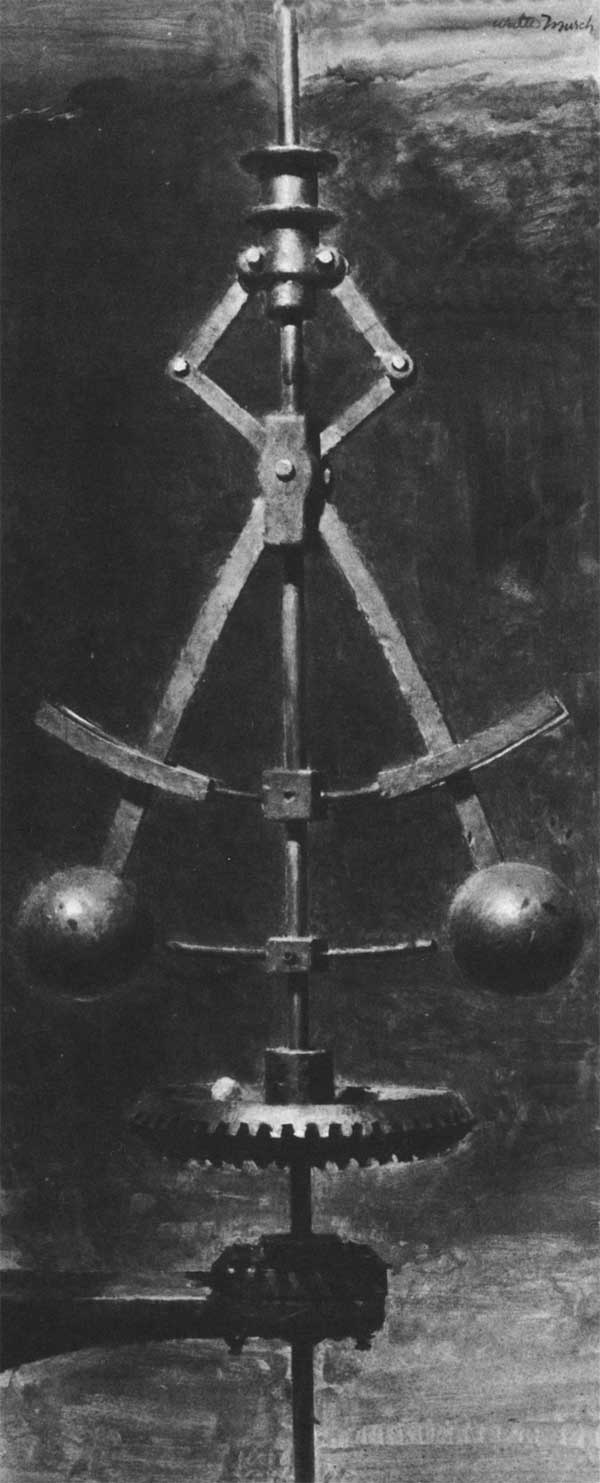

Walter Murch’s soft-focus, hyperrealistic grisaille painting “Governor, II” (1952)

turns the works of an antique timepiece into a numinous, Newtonian metaphor. John Wilde’s 1943 self-portrait, drawn in pencil with exquisite refinement, resembles the work of a Renaissance neo-Platonist.What is the spiritual catastrophe that seems to have almost all these artists in its grip, driving so many of them into morbid withdrawal from the can-do business of modern life?

Consider

Peter Blume’s “Light of the World” (1932),

a compact, nearly square panel painting made in the crystalline style of a Northern Renaissance master. Three rotund people gaze up at a bizarre rooftop construction: a central pole with decorative architectural fragments attached, topped by a cut-glass globe with glowing light bulbs inside. The title may be taken literally: electricity does light our world, after all. But it also invokes Jesus’ declaration “I am the light of the world,” and you do not have to be a Christian to appreciate how the promises of technology supplanted those of religion early in the 20th century, leaving a secularized world unmoored from spiritual foundations.

“Winter Fields,” a painting that Andrew Wyeth made in 1942 when he was leaning toward Magic Realism, puts it more succinctly. With the exacting touch and the pagan religiosity of a Pre-Raphaelite, he pictured a dead crow among dry, brown grasses, a baleful symbol for civilization at war with itself, a silent scream against the violent idiocy of man.