The Städel Museum hosted an exhibition on

Sandro Botticelli (1444/45–1510) from 13 November 2009 to 28 February 2010.

Taking the artist’s monumental

Idealized Portrait of a Lady,

one of the Städel

Museum collection’s highlights, as its starting point, the exhibition presented

numerous works from all productive periods of this great master of the

Renaissance in Italy about 500 years after his day of death (17 May 1510).

The

exhibition opened with portraits and allegorical paintings that illustrate the

degree of sophistication with which Botticelli drew on this highly developed

genre and enriched it with new impulses. While the second section centered on

his famous mythological representations of goddesses and heroines of virtue,

the third part iwa dedicated to his abundant religious oeuvre.

With

a total of more than forty works by Botticelli and his workshop, the show

presented a comprehensive selection of his work surviving worldwide. Forty

further exhibits, among them works by such contemporaries as Andrea del

Verrocchio, Filippino Lippi, and Antonio del Pollaiuolo, will allow to

understand Botticelli’s precious creations in the historical context of their

genesis.

The

presentation was supported by outstanding loans from the most important

collections of paintings in Europe and the United States. These include the

Uffizi Gallery in Florence, the Louvre in Paris, the National Gallery London,

the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, and the Old Masters Picture Gallery in Dresden,

as well as the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the National Gallery of Art

in Washington.

Sandro

Botticelli’s painting has become a landmark of Italian Renaissance. The

delicate beauty, elegant grace, and unique charm of his frequently melancholic

figures make his work the epitome of Florentine painting in the Golden Age of

Medici rule under Lorenzo the Magnificent. Initially trained as a goldsmith and

then apprenticed to Fra Filippo Lippi, Sandro Botticelli soon ranked among the

most successful painters in Florence in the second half of the quattrocento

next to Verrocchio, Ghirlandaio, and the Pollaiuolo brothers. From 1470 on, he

received prestigious public commissions and established himself as a painter of

large altarpieces.

Throughout his life, Botticelli was in the ruling Medici

family’s and their supporters’ good graces. Fulfilling their wishes for innovative

decorative paintings, the master could not only rely on his personal knowledge

of Florentine traditions and of ancient art, but also on definite suggestions

and concepts from the circle of humanists gathered around Lorenzo de’ Medici.

Held in equally high esteem as both a panel and a fresco painter, Botticelli

enjoyed a high standing beyond his native Florence and was thus one of the artists summoned to

decorate the walls of the Sistine Chapel in Rome by Pope Sixtus IV in 1481. It was

particularly his much-discussed late work that brought out the characteristic

features of his original style in an extreme manner.

Guided

by the art of drawing – the exhibition includedan outstanding selection of

preparatory sketches – Botticelli followed his penchant for presenting his figures

with sharp contours, strong movements, and abundant gestures, grounding his

compositions on textures of lines and surfaces rather than on spaces and

volumes. In this respect, his painting had already stood out against his

competitors’ works and current theoretical demands in his early years.

The

starting point and center of the cross-genre exhibition was provided by a main

work from the collection of the Städel Museum not only very well known in

Frankfurt: the master’s idealized portrait of a young lady, who is probably to

be identified with Simonetta Vespucci, the beloved jousting tournament lady of

Lorenzo’s brother Giuliano de’ Medici. This portrait is less aimed at a true-to-life

likeness of the subject than at the ideal of a woman characterized by perfect

beauty and equally perfect virtuousness, an ideal also reflected in the poetry

of that time. Such an ideal defines itself not least through its rapport with

antiquity: thus, the beautiful female wears a piece of jewelry round her neck

which is obviously based on an ancient cameo showing Apollo and Marsyas, which wasalso

be on display in the exhibition.

In

the Städel Museum,

Botticelli’s famous portrait of Giuliano from the National Gallery of Art in Washington

offered itself for comparison with his beloved Simonetta’s likeness. Both paintings make up the center of the first part of the presentation, which is devoted to Botticelli’s art of portraiture and, drawing on prominent examples, illustrates the interplay between social norm and artistic form as well as the different genre conventions of the male and the female portrait.

Botticelli’s famous portrait of Giuliano from the National Gallery of Art in Washington

offered itself for comparison with his beloved Simonetta’s likeness. Both paintings make up the center of the first part of the presentation, which is devoted to Botticelli’s art of portraiture and, drawing on prominent examples, illustrates the interplay between social norm and artistic form as well as the different genre conventions of the male and the female portrait.

The

second section of the exhibition dealt with Botticelli’s mythological pictures,

which number among the artist’s most original creations. The Uffizi Gallery in

Florence, which safeguards the most comprehensive and significant collection of

works by the artist in the world, supported the exhibition in Frankfurt with

one of its most popular works among others loans: the famous

Pallas and the Centaur,

one of Botticelli’s monumental mythological paintings, to be seen in the context of Medicean self-presentation.

Together with Botticelli’s

Primavera,

it once adorned the walls of a bedchamber in a Florentine palace owned by the family of bankers. We see Pallas taming the wild centaur indulging in his passions through her wisdom and virtue. The control and cultivation of emotions was a central issue in ancient philosophy and – combined with Christian thought – of the Renaissance, too; among the painters of the time, Botticelli offered himself as a congenial interpreter for such subjects. The political dimension and the reference to the patron family are symbolically present in the form of two intertwined diamond rings on Pallas’s gown, which were an emblem of the Medici family.

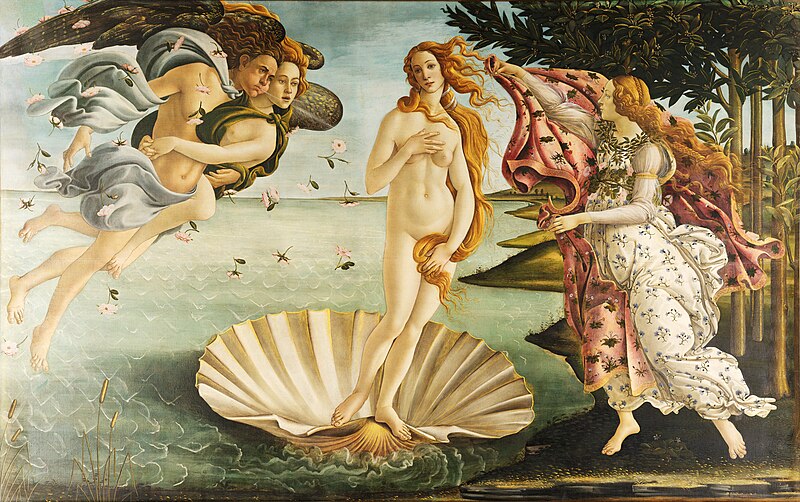

Another great female figure featuring in the Florentine artist’s oeuvre is the goddess Venus. His life-size

Venus from the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin

is a repetition of the central figure of (the unloanable)

Birth of Venus in the Uffizi Gallery,

which he isolated from the context of the scene and set off against a black background. This work is one of the first monumental nudes of postancient painting.

Pallas and the Centaur,

one of Botticelli’s monumental mythological paintings, to be seen in the context of Medicean self-presentation.

Together with Botticelli’s

Primavera,

it once adorned the walls of a bedchamber in a Florentine palace owned by the family of bankers. We see Pallas taming the wild centaur indulging in his passions through her wisdom and virtue. The control and cultivation of emotions was a central issue in ancient philosophy and – combined with Christian thought – of the Renaissance, too; among the painters of the time, Botticelli offered himself as a congenial interpreter for such subjects. The political dimension and the reference to the patron family are symbolically present in the form of two intertwined diamond rings on Pallas’s gown, which were an emblem of the Medici family.

Another great female figure featuring in the Florentine artist’s oeuvre is the goddess Venus. His life-size

Venus from the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin

is a repetition of the central figure of (the unloanable)

Birth of Venus in the Uffizi Gallery,

which he isolated from the context of the scene and set off against a black background. This work is one of the first monumental nudes of postancient painting.

The

third and last section of the exhibition was devoted to Botticelli’s religious

pictures. Next to his portraits and mythological works, Botticelli has owed his

continuing fame to his Madonnas. According to theological thinking, Mary stands

out as the ideal woman among the saints: she is the most virtuous and the most

beautiful female, the bride of the Song of Songs. Besides many other works

spanning from Botticelli’s earliest works still revealing the influence of his

teacher Fra Filippo Lippi to examples of his late style, the exhibition in

Frankfurt shows one of the artist’s most beautiful Madonnas:

The Virgin Adoring the Sleeping Christ Child.

The Madonna’s physiognomy of this painting from the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, whose brilliant colorfulness has only been uncovered through restorative measures some years ago, is rendered in the vein of the same female model which the painter developed for his idealized portraits and pictures of ancient goddesses. This chapter also includes a number of narrative pictures, such as a removed Annunciation fresco once to be found in the vestibule of the hospital of San Martino alla Scala in Florence and preserved in the Uffizi Gallery today. Not only the enormous size of the fresco (243 x 550 cm), but also its qualities as a painting testify to Botticelli’s extraordinary importance in this medium. Four panels depicting scenes from the life of St. Zenobius, an early bishop and patron of Florence, offer a further highlight, with which the exhibition ends. Usually scattered to museums in London, Dresden, and New York, they have been brought together for the first time in Frankfurt again. Ranking not only among his most significant late works, but also among his very last, the panels are to be considered as Botticelli’s legacy as an artist.

The Virgin Adoring the Sleeping Christ Child.

The Madonna’s physiognomy of this painting from the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, whose brilliant colorfulness has only been uncovered through restorative measures some years ago, is rendered in the vein of the same female model which the painter developed for his idealized portraits and pictures of ancient goddesses. This chapter also includes a number of narrative pictures, such as a removed Annunciation fresco once to be found in the vestibule of the hospital of San Martino alla Scala in Florence and preserved in the Uffizi Gallery today. Not only the enormous size of the fresco (243 x 550 cm), but also its qualities as a painting testify to Botticelli’s extraordinary importance in this medium. Four panels depicting scenes from the life of St. Zenobius, an early bishop and patron of Florence, offer a further highlight, with which the exhibition ends. Usually scattered to museums in London, Dresden, and New York, they have been brought together for the first time in Frankfurt again. Ranking not only among his most significant late works, but also among his very last, the panels are to be considered as Botticelli’s legacy as an artist.

Curator:

Dr. Andreas Schumacher (Städel Museum)

Research

assistants: Gabriel Dette M.A. and Dr. Bastian Eclercy (Städel Museum)

Exhibition

architecture: Nikolaus Hirsch & Michel Müller Architekten, Michiko Bach

Catalogue:

On the occasion of the exhibition, a comprehensive catalogue edited by Andreas Schumacher and comprising an introduction by Max Hollein and texts by Cristina Acidini, Gabriel Dette, Bastian Eclercy, Hans Körner, Lorenza Melli, Ulrich Rehm, Volker Reinhardt, Anna Rühl, and Andreas Schumacher was published by Hatje Cantz. German and English editions.

On the occasion of the exhibition, a comprehensive catalogue edited by Andreas Schumacher and comprising an introduction by Max Hollein and texts by Cristina Acidini, Gabriel Dette, Bastian Eclercy, Hans Körner, Lorenza Melli, Ulrich Rehm, Volker Reinhardt, Anna Rühl, and Andreas Schumacher was published by Hatje Cantz. German and English editions.