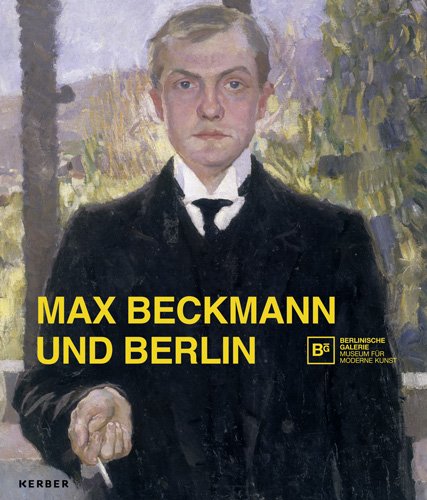

To mark its 40th anniversary, the Berlinische Galerie presents "Max Beckmann and Berlin“. This is the first major Beckmann exhibition in Berlin in 30 years, and the first devoted to the decisive role the city played in the artist ́s life and work. There are 50 exhibits from the period between 1905 and 1936, including numerous self-portraits and key works loaned by eminent institutions or drawn from the museum‘s own collection, including

“The Flood” (1908),

“Women’s Bath” (1919),

Alongside them hang paintings by celebrated contemporaries such as Edvard Munch, Max Lieberman, Franz Marc and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. “Max Beckmann is the new Berlin,” declared the art historian Julius Meier-Graefe in 1924. The exhibition illustrates Beckmann’s journey to become one oft he leading protagonistis of modern art. It recounts how the young and unknown artist fought off crises and failures in Berlin, developed a style of his own, and ultimately made his mark not only the city, but across the world. The works on display were produced in Berlin, are thematically associated with the city, or were chosen for its great exhibitions and set their stamp on its art scene. The self-portraits from very different creative periods reveal how the artist saw himself and his circumstances at the time.

Works by contemporaries cast spotlights of their own on Berlin’s vibrant and versatile artistic output from the turn oft he century until the 1920s.

Max Beckmann (1884 –1950) lived initally in Berlin for 10 years (1904 until 1914). After studying art in Weimar and a staying shortly in Paris, he obtained his first studio here in the autumn of 1904. At 20 years old, the ambitious artist tried to distinguish himself in the capital city, one of the most important modern centers.

His first Berlin work

Max Beckmann,

Junge Männer am Meer, 1905, Klassik Stiftung Weimar, © VG BILD-KUNST Bonn, 2015, Repro: Renno, Weimar

“Young Men by the Sea” (1906) already brought him much attention and acknowledgements. Henceforth Beckmann was sponsored by the Weimar museum director and patron Harry Graf Kessler, whose portrait by Edvard Munch can be seen in the exhibition. “Young Men by the Sea”also impressed the gallery owner Paul Cassirer, who then included Beckmann in his program and promoted his works for many years. His works were regularly displayed in the Berliner Secession as well. To Beckmann’s disappointment, his trainedImpressionism style could not prevail over the newly emerged Expressionism.

It was in Berlin in 1919 that Max Beckmann’s lithographic series

Die Hölle (Hell) was published, one of the seminal print cycles of the early Weimar years. It was followed in 1922 by the portfolio

Max Beckmann,

aus dem Mappenwerk "Berliner Reise", Blatt 4: Nackttanz, 1922, Berlinische Galerie, Leihgabe des Landes Berlin, © VG BILD-KUNST Bonn, 2015, Repro: Kai-Annett Becker

Berliner Reise 1922 (Trip to Berlin 1922), which the Berlinische Galerie has just acquired for its own collection. These two cycles were pictorial commentaries on recent history and they contain many references to Berlin.

The painter entered World War I as a medic, which unsettled him greatly. Backmann moved to Frankfurt am Main and stayed there for many years, mentally ailing and disappointed from the Berlin art scene. He gathered new strength and found a new style here. He wanted to conquer Berlin and the world, as stated in letters written in 1926: “Berlin, Dresden, Munich, and then Paris and New York.” It was in this year that Beckmann’s first important works found their way into the collection of the Berliner Nationalgalerie. Included was the painting

“Mardi gras parisino” (1930),

which a contemporary described in its first year as “one of the greatest achievements of contemporary art.”

A last, and for Beckmann overdue, success could be celebrated in Berlin in 1933: Ludwig Justi, the director of the Nationalgalerie Berlin, devoted him a room entirely to his work in the New Department of the Nationalgalerie. Shortly before, Adolf Hitler was named Chancellor of the Reich. Then unfortunately in the summer of 1933, the National Socialist Regime temporarily ordered to close the Kronprinzenpalais.

Beckmann’s works were found “entartet” (degenerate) and the artist was released from his office at the Städelschule in Frankfurt am Main. He moved with his second wife Mathilde, called “Quappi” from Frankfurt back to Berlin. There, prior to emigrating to Amsterdam in 1937, he produced motifs of the city, portraits of his wife,

Max Beckmann,

Quappi mit Papagei, 1936,

Kunstmuseum Mülheim an der Ruhr,

© VG BILD-KUNST Bonn, 2015

“Quappi with Parrot” (1936), and also his earliest triptychs and mythologically inspired works like

“The Hurdy-Gurdy Man” (1935), and also – for the first time – sculptures. After leaving for Amsterdam in July 1937, Beckmann never returned to the country of his birth.

The exhibition is accompanied by a detailed catalogue in German and English reflecting the latest research on the theme of Max Beckmann and Berlin.

More images from the exhibition:

Max Beckmann,

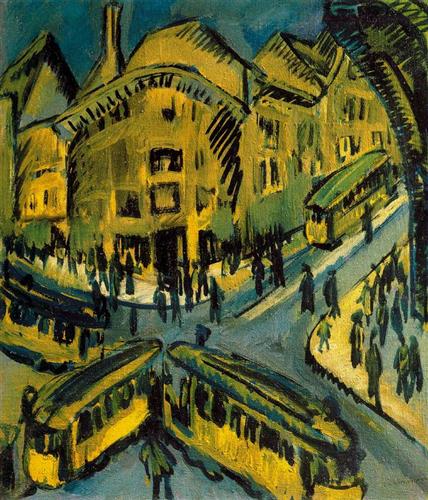

Blick auf den Nollendorfplatz, 1911, Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin, © VG BILD-KUNST Bonn, 2015

From an outstanding review (read the whole thing);{images added}

Max Beckmann,

Die Straße (Teil einer großformatigen Straßenszene, die Beckmann 1928 zerschnitten hat), 1914,

Berlinische Galerie, © VG BILD-KUNST Bonn, 2015

Die Straße (Teil einer großformatigen Straßenszene, die Beckmann 1928 zerschnitten hat), 1914,

Berlinische Galerie, © VG BILD-KUNST Bonn, 2015

Max Beckmann,

Blick auf den Nollendorfplatz, 1911, Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin, © VG BILD-KUNST Bonn, 2015

From an outstanding review (read the whole thing);{images added}

Straight away, you’re bound to get drawn into the first painting Beckmann made in Berlin, “Young Men by the Sea” (1906), (above) a large-scale, picturesque scene of nude, muscular men loitering on the beach, choppy waters and dramatic clouds in the distance. Right next to it is a very similar image,

Max Liebermann’s “Bathing Boys” (1907). The theme, use of colour modulation and similarities between the two make a great case for the influence German Impressionism (Liebermann’s camp) had on Beckmann as a young painter.

In the same room is a pairing that is stylistically dissimilar yet closely related:

Beckmann’s “Small Death Scene” (1906)

and Edvard Munch’s lithograph “The Death in the Sickroom” (1896), each depicting quietly distraught mourners, with their deceased loved ones in the background. Comparing the two is interesting in its own right, but make sure to glance back at “Young Men by the Sea,” painted the same year, yet astonishingly different. Beckmann’s artistic agility, employing diverse sets of colours, brushstrokes and compositions, is already vivid in the first room.

“The Flood” (1908) commands the second room of the exhibition, exemplary of his controversial push back against the burgeoning Expressionism of the day. This work could not be more different in style and mood than

“Girl with Cat II” (1912) by Franz Marc, who had a heated public debate with Beckmann over the new movement...

The third room is dedicated to the bustling metropolis Beckmann temporarily called home. Other paintings provide comparisons to the Berlin of today –

“Kaiserdamm” (1911), a peaceful, snowy European boulevard scene with a decadent purple sky

and “Tauentzienstraße” (1913), which offers a view of the pre-war Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche, as if seen from the front door of the recently opened KaDeWe.

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s “Nollendorfplatz” (1912) brings you back from the delight of studying the Berlin of the past, to considering the dramatic variations in depicting it....

Turning the corner out of the last room, you are met with Beckmann himself, in the form of several self-portraits made throughout his life, for which he is much celebrated. Here, too, a major jump occurs in

Max Beckmann,

Selbstbildnis mit Sektglas, 1919, Privatsammlung, Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main, Dauerleihgabe, © VG BILD-KUNST Bonn, 2015

“Self-Portrait with Champagne Glass” (1919).

Max Beckmann,

Selbstbildnis Florenz, 1907,

Hamburger Kunsthalle, Leihgabe aus einer Privatsammlung,

© VG BILD-KUNST Bonn, 2015, Foto: Elke Walford

Seen alongside “Self-Portrait, Florence” (1907), you wouldn’t guess they were painted by the same man.

_-_1906.jpg/421px-Max_Beckmann_-_Kleine_Sterbeszene_(Small_Death_Scene)_-_1906.jpg)