Musée

Jacquemart-André

18 March - 25 July 2016

This

spring, the Musée Jacquemart-André is presenting an ensemble of some fifty or

so prestigious artworks—from both private collections and major American and

European museums—that retrace the history of Impressionism, from the

forefathers of the movement to the Great Masters.

The 19th century saw the

emergence of a new pictorial genre: ‘plein-air’ or outdoor landscape painting.

This pictorial revolution, born in England, would spread to the continent in

the 1820s and over the course of a century, Normandy would become the preferred

destination of many avant-garde painters. The region’s stunning and diverse

landscapes, coupled with the wealth of its architectural heritage, had much to

please artists.

Furthermore, the growing fashion for sea-bathing attracted many wealthy individuals and families who could easily access Normandy by either boat or stage-coach, and later by train. Its popularity was also increased due to its enviable location—halfway between London and Paris, the two art capitals of the period.

Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, British landscape artists such as Turner, Bonington, and Cotman travelled to Normandy, with their boxes of watercolours, while the French—Géricault, Delacroix, Isabey—made their way to London to discover the English school.

From these exchanges, a French landscape school was born, with Corot and Huet at the helm. In their wake, another generation of painters would in turn explore the region (Delacroix, Riesener, Daubigny, Millet, Jongkind, Isabey, Troyon), inventing a new aesthetic. This artistic revolution truly began to take form at the beginning of the 1860s, the fruit of lively discussions and exchanges at the Saint-Siméon Farm in Honfleur on Normandy’s Flower Coast, increasingly popular with the crème de la crème of this new school of painting. These included Boudin, Monet and Jongkind—an inseparable trio—but also their friends: Courbet, Daubigny, Bazille, Whistler, and Cals...And of course, Baudelaire, who was the first to celebrate in 1859, the ‘meteorological beauties’ of Boudin’s paintings.

Not far away, in the hedgerows and woodlands of the Normandy countryside, Degas painted his first horse races at Haras-du-Pin and Berthe Morisot took up landscape painting, while at Cherbourg, Manet would revolutionize seascapes. For several decades, Normandy would be the preferred outdoor or ‘plein-air’ studio of the Impressionists. Monet, Degas, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, Boudin, Morisot, Caillebotte, Gonzales, and Gauguin would all experiment with their art here in a constant quest for originality and innovation.

The aim of this exhibition is to evoke the decisive role played by Normandy in the emergence of the Impressionist movement, through exchanges between French and British landscape painters, the development of a school of nature and the encounters between artists at Saint-Siméon. From a historical to a geographic approach, the exhibition then shows how the Normandy landscape, especially the quality of its light, were critical in the attraction that the region had on the Great Impressionist Masters

Furthermore, the growing fashion for sea-bathing attracted many wealthy individuals and families who could easily access Normandy by either boat or stage-coach, and later by train. Its popularity was also increased due to its enviable location—halfway between London and Paris, the two art capitals of the period.

Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars, British landscape artists such as Turner, Bonington, and Cotman travelled to Normandy, with their boxes of watercolours, while the French—Géricault, Delacroix, Isabey—made their way to London to discover the English school.

From these exchanges, a French landscape school was born, with Corot and Huet at the helm. In their wake, another generation of painters would in turn explore the region (Delacroix, Riesener, Daubigny, Millet, Jongkind, Isabey, Troyon), inventing a new aesthetic. This artistic revolution truly began to take form at the beginning of the 1860s, the fruit of lively discussions and exchanges at the Saint-Siméon Farm in Honfleur on Normandy’s Flower Coast, increasingly popular with the crème de la crème of this new school of painting. These included Boudin, Monet and Jongkind—an inseparable trio—but also their friends: Courbet, Daubigny, Bazille, Whistler, and Cals...And of course, Baudelaire, who was the first to celebrate in 1859, the ‘meteorological beauties’ of Boudin’s paintings.

Not far away, in the hedgerows and woodlands of the Normandy countryside, Degas painted his first horse races at Haras-du-Pin and Berthe Morisot took up landscape painting, while at Cherbourg, Manet would revolutionize seascapes. For several decades, Normandy would be the preferred outdoor or ‘plein-air’ studio of the Impressionists. Monet, Degas, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, Boudin, Morisot, Caillebotte, Gonzales, and Gauguin would all experiment with their art here in a constant quest for originality and innovation.

The aim of this exhibition is to evoke the decisive role played by Normandy in the emergence of the Impressionist movement, through exchanges between French and British landscape painters, the development of a school of nature and the encounters between artists at Saint-Siméon. From a historical to a geographic approach, the exhibition then shows how the Normandy landscape, especially the quality of its light, were critical in the attraction that the region had on the Great Impressionist Masters

For

a long time, the history of Impressionism has been understood as having a

relatively short chronology, beginning in 1863 with the Salon des Refusés and

ending in 1886 with the 8thExposition Impressioniste. This approach assigned a

crucial role to Paris and the Île-de-France region but very little to other

areas of France and to foreign influences.

Research carried out over the past thirty or so years has led us to reconsider the history of the movement and to situate it within a longer time frame which puts the origins or roots of Impressionism at the beginning of the 1820s. This new approach also underlines the influence of the English School in the birth of a French Landscape School and assigns Normandy a decisive role in the emergence of the Impressionist movement.

Several factors may explain why Normandy was the birthplace of Impressionism

• its geographical location, half-way between London and Paris, the two artistic epicentres of the time

(Courbet, L’Embouchure de la Seine also known as Vue prise des hauteurs de Honfleur, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille).

• the region’s rich architectural heritage at a time when artists played an active role in its preservation and promotion

(Corot, Jumièges, Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton) ;

in 1820 Isidore Taylor published his Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l’ancienne France, with the first two volumes devoted to Normandy. In 1825, Victor Hugo published an essay on the preservation of French patrimonial monuments entitled Guerre aux démolisseurs.

• the fashion for sea-bathing, imported from England, which became popular in Dieppe circa 1820, before spreading along the Channel coastline.

• the beauty and diversity of the region’s landscapes, as well as the subtlety and versatility of the light, in an era when landscape painting became a genre in its own right and when painters began to leave their studios to paint nature as they saw it, outdoors and in natural light.

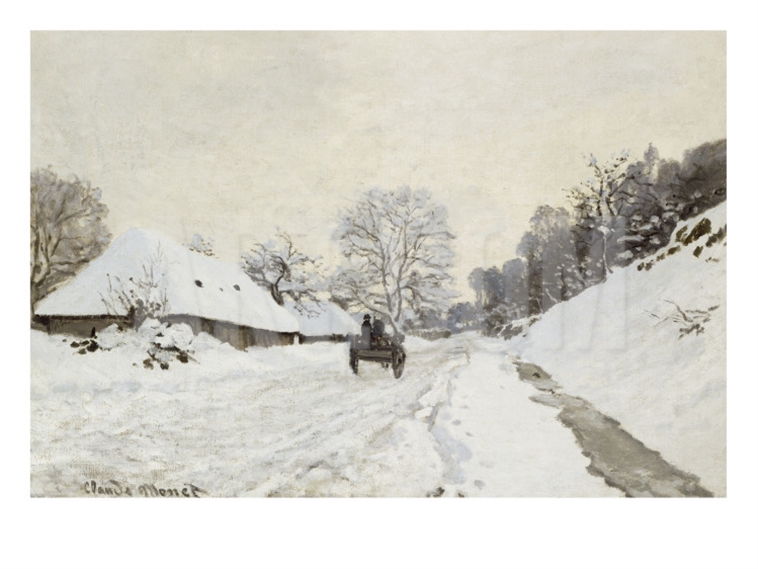

(Monet, La Charrette. Route sous la neige à Honfleur avec la ferme Saint-Siméon, Musée d’Orsay, Paris).

• ease of access by river and later by train. Railway lines between Paris and the Normandy coast were amongst the first to be created, facilitating the growing popularity of seaside resorts.

Research carried out over the past thirty or so years has led us to reconsider the history of the movement and to situate it within a longer time frame which puts the origins or roots of Impressionism at the beginning of the 1820s. This new approach also underlines the influence of the English School in the birth of a French Landscape School and assigns Normandy a decisive role in the emergence of the Impressionist movement.

Several factors may explain why Normandy was the birthplace of Impressionism

• its geographical location, half-way between London and Paris, the two artistic epicentres of the time

(Courbet, L’Embouchure de la Seine also known as Vue prise des hauteurs de Honfleur, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille).

• the region’s rich architectural heritage at a time when artists played an active role in its preservation and promotion

(Corot, Jumièges, Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton) ;

in 1820 Isidore Taylor published his Voyages pittoresques et romantiques dans l’ancienne France, with the first two volumes devoted to Normandy. In 1825, Victor Hugo published an essay on the preservation of French patrimonial monuments entitled Guerre aux démolisseurs.

• the fashion for sea-bathing, imported from England, which became popular in Dieppe circa 1820, before spreading along the Channel coastline.

• the beauty and diversity of the region’s landscapes, as well as the subtlety and versatility of the light, in an era when landscape painting became a genre in its own right and when painters began to leave their studios to paint nature as they saw it, outdoors and in natural light.

(Monet, La Charrette. Route sous la neige à Honfleur avec la ferme Saint-Siméon, Musée d’Orsay, Paris).

• ease of access by river and later by train. Railway lines between Paris and the Normandy coast were amongst the first to be created, facilitating the growing popularity of seaside resorts.

William Turner (1775-1851) Lillebonne, 1823 Watercolour, gouache, brown and black ink13,4 x 18,5 cm Oxford, The Ashmolean Museum. Presented by John Ruskin, 1861© Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

The

Open-Air Studio The Impressionists in Normandy

The

coastline was traditionally the preserve or domain of fishermen. This was where

they unloaded their cargo or mended their nets, or where their wives would wash

laundry or collect shellfish.

(Boudin, Marée basse à Trouville, pêcheurs de crevettes, Association Peindre en Normandie, Caen).

(Boudin, Marée basse à Trouville, pêcheurs de crevettes, Association Peindre en Normandie, Caen).

With

the fashion for sea-bathing, the coastline was transformed into a beach, a

place now shared between the workers of the sea and summer holidaymakers at

seaside resorts.

(Monet, Sur les planches de Trouville, hôtel des Roches noires, collection particulière).

On the one hand, there existed a working class that was increasingly sidelined, and on the other hand, an aristocracy and upper middle class who came to the Normandy coast to take advantage of the fresh air and sea-bathing, with a social life akin to the capital’s. Hence the creation of promenades (the famous wooden boardwalks in Trouville and Deauville); race tracks

(Degas, Course de gentlemen. Avant le départ, Musée d’Orsay, Paris);

bandstands where concerts were held; casinos for betting, and attending operettas or plays. Soon tennis clubs based on the English model would open up all along the coast. All of these venues were places of conviviality and a means of social segregation.

(Monet, Sur les planches de Trouville, hôtel des Roches noires, collection particulière).

On the one hand, there existed a working class that was increasingly sidelined, and on the other hand, an aristocracy and upper middle class who came to the Normandy coast to take advantage of the fresh air and sea-bathing, with a social life akin to the capital’s. Hence the creation of promenades (the famous wooden boardwalks in Trouville and Deauville); race tracks

(Degas, Course de gentlemen. Avant le départ, Musée d’Orsay, Paris);

bandstands where concerts were held; casinos for betting, and attending operettas or plays. Soon tennis clubs based on the English model would open up all along the coast. All of these venues were places of conviviality and a means of social segregation.

Under

the Second Empire (1852 – 1870), a period of industrialization during which

many families amassed large fortunes, the concept of summer holidays became

hugely popular. New seaside resorts sprung up all along the Flower Coast (Côte

Fleurie) between Deauville and Cabourg. The emergence of a ‘lifestyle of

leisure’ chronicled by the painters of the time was a godsend to many artists

who had previously struggled to sell their ‘seascapes’ and who could now

command high prices for their ‘beach scenes’. This genre, invented by Eugène

Boudin in 1862 would be imitated by all of his Impressionist friends

(Boudin, Crinolines à Trouville, collection particulière).

(Boudin, Crinolines à Trouville, collection particulière).

Claude Monet(1840-1926) Sur les planches de Trouville, hôtel des Roches noires, détail 1870 50 x 70 cm, oil on canvas Collection particulière © Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images

Rooms

2 & 3

Beaches,

leisure and society life

The

coastline of the English Channel, with its tumultuous tides and impressive

storms, had long inspired a romantic vision of the sea, as skilfully depicted

in the work of both Eugène Isabey and William Turner. However as seaside

resorts grew, painters devoted themselves to a new vision of their marine

environment. They became less interested in the sea itself and more in its

natural and human environment

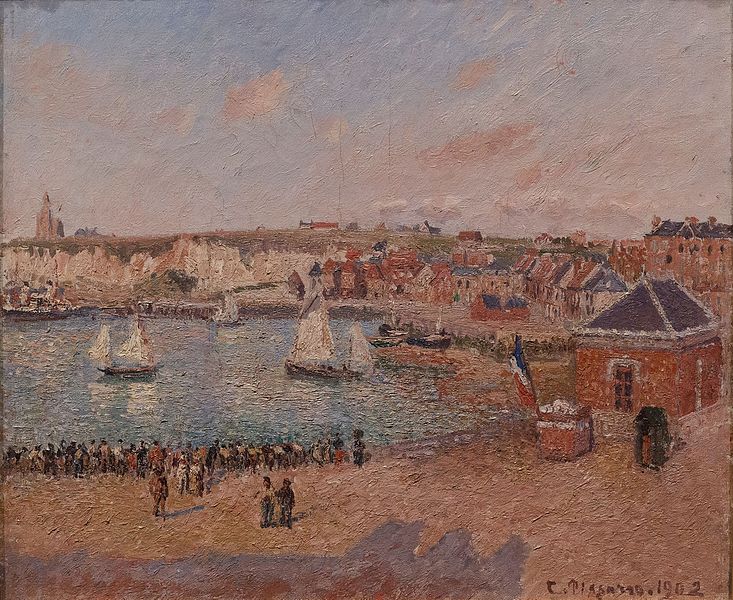

(Pissarro, Avant-port de Dieppe, après-midi, soleil, Château-Musée de Dieppe).

With its ports teeming with boats, stretching from Tréport to the bay of Mont-Saint-Michel, and its sheer cliffs, where the whiteness of the chalk contrasted with the verdant grass covering, the Channel coastline offered an infinite variety of subjects and motifs to be painted

(Gauguin,Le Port de Dieppe, Manchester City Galleries).

Dieppe, which was the first seaside resort to be created in the 1820s, attracted many of the leading figures of this new style of painting (Monet, Renoir, Degas, Boudin, Pissarro and Gauguin) following the War of 1870, as well as artists Blanche, Gervex and Helleu, referred to as ‘society painters’ (one should of course pay little heed to such artificial classifications). It also attracted other unclassifiable artists like Eva Gonzalès, Manet’s only student and last but not least, a large number of Anglo-Saxon artists

(Pissarro, Avant-port de Dieppe, après-midi, soleil, Château-Musée de Dieppe).

With its ports teeming with boats, stretching from Tréport to the bay of Mont-Saint-Michel, and its sheer cliffs, where the whiteness of the chalk contrasted with the verdant grass covering, the Channel coastline offered an infinite variety of subjects and motifs to be painted

Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) Le Port de Dieppe, around 1885 60,2 x 72,3 cm, oil on canvas Manchester, Royaume-Uni, Manchester City Galleries© Manchester Art Gallery, UK / Bridgeman Images

(Gauguin,Le Port de Dieppe, Manchester City Galleries).

Dieppe, which was the first seaside resort to be created in the 1820s, attracted many of the leading figures of this new style of painting (Monet, Renoir, Degas, Boudin, Pissarro and Gauguin) following the War of 1870, as well as artists Blanche, Gervex and Helleu, referred to as ‘society painters’ (one should of course pay little heed to such artificial classifications). It also attracted other unclassifiable artists like Eva Gonzalès, Manet’s only student and last but not least, a large number of Anglo-Saxon artists

room

4

From

ports to cliffs – Dieppe

For

artists in search of subject matter to paint, Normandy’s Alabaster Coast

provided plenty of examples of stunning natural architecture: immense

panoramas, a rugged coastline of estuaries and valleys, and huge white chalk

cliffs, eroded by the sea and the wind. Maupassant would compare the natural

cliff arches of Manneport d’Étretat to an ‘enormous cave through which a ship

with all its sails unfurled could pass’ and the Porte d’Amont to ‘the huge

figure of an elephant’s trunk plunged into the waves’.But above all what

Courbet, Monet, Renoir and Berthe Morisot sought in this section of the coast

were the incredible chromatic variations of the sea and the sky, connected to

the ebb and flow of the tides, the passing wind and the clouds, and the sea

spray. These continuous atmospheric changes were for them a powerful stimulus

to work quickly, without getting too bogged down in detail, so as to be able to

render the smallest nuances in the light

(Monet, Falaises à Varengeville also known as Petit-Ailly, Varengeville, plein soleil, Musée d’art moderne André Malraux, Le Havre).

The central place given to the treatment of the light would bring Courbet, in 1869, to experiment with the process of making series of paintings, depicting for example the cliffs at Étretat in different light

(Courbet, La Falaise d’Étretat, Van der Heydt-Museum, Wuppertal).

In the 1880s and 1890s, Monet would also use this process, painting numerous depictions of cliffs, from those at Petites-Dalles in Fécamp to ones at Étretat, Varengeville, Porville and Dieppe

(Monet, Falaises à Varengeville also known as Petit-Ailly, Varengeville, plein soleil, Musée d’art moderne André Malraux, Le Havre).

The central place given to the treatment of the light would bring Courbet, in 1869, to experiment with the process of making series of paintings, depicting for example the cliffs at Étretat in different light

(Courbet, La Falaise d’Étretat, Van der Heydt-Museum, Wuppertal).

In the 1880s and 1890s, Monet would also use this process, painting numerous depictions of cliffs, from those at Petites-Dalles in Fécamp to ones at Étretat, Varengeville, Porville and Dieppe

Claude Monet Etretat, la porte d’Aval, bateaux de pêche sortant du port, around1885 60 x 80 cm, oil on canvas Dijon, Musée des Beaux-Arts© Musée des beaux-arts de Dijon Photo François Jay

room

5

From

ports to cliffs - The Alabaster Coast

Towards

the middle of the century a new means of transport appeared: the train, which

would completely revolutionize travel. Railway lines between Paris and the

Normandy coast were amongst the first to be created. The Paris-Rouen line was

opened in 1843, extended to Le Havre in 1847, to Dieppe the following year, and

in 1856 to Fécamp. In the 1860s, trains stopped at Deauville-Trouville and all

the other seaside resorts along the Flower Coast. In their advertising

campaigns, railroad companies highlighted the fact that travellers could reach

the coast in two to three hours. There were even special trains running for

certain events, such as the naval battles of the American Civil War fought off

the coast of Cherbourg, attended by Manet in 1864.The train was not only used

by Parisian artists (Morisot, Degas, Manet, Caillebotte, etc.) seeking to leave

the capital and to soak up the fresh sea air at the coast in their quest for

new subject matter to paint. It was also used by painters from Normandy

(Boudin, Monet, Dubourg, Lépine, Lebourg, etc.) who travelled to Paris to

exhibit their work at the Salon, visiting exhibitions, meeting with fellow

artists, as well as art dealers and collectors during their stay.

Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) La Plage des Petites-Dalles, around 1873 24,1 x 50,2 cm, oil on canvas Richmond, Virginie, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Collection of Mr and Mrs Paul Mellon © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts/Katherine Wetzel

room

6

The

railroad

Claude Monet(1840-1926) Barques de pêche, Honfleur, around 1866 46 x 55 cm, oil on canvas Collection particulière© Collection particulière

Like

the Alabaster Coast, the ports and coastline stretching from Le Havre to

Cherbourg would equally captivate Boudin, Monet and Pissarro, as well as Berthe

Morisot, Degas, Signac, Seurat and many other landscape artists. Amongst them,

was a practically unknown painter: Charles Pécrus, converted by his friend

Boudin to the art of landscape painting and whose very lively port scenes would

owe a lot to Boudin’s influence (Pécrus, Le Port de Honfleur, Association

Peindre en Normandie, Caen).Towards the end of his life, Boudin would adopt an

even brighter palette and an even bolder and freer brushstroke. Pursuing his

passionate quest for light, he would focus on the shimmering reflections of the

water, the vibrations of the air, and the clouds as they raced across an

enormous sky (Entrée du port du Havre par grand vent, Collection particulière,

Courtesy Galerie de la Présidence, Paris).

This sensitive, delicate art is completely removed from the vigorous representations—heralding the Expressionist and Fauvist movements—which Monet, at the beginning of his career, would produce of fishing boats moored in the port of Honfleur (Barques de pêche, collection particulière, et Bateaux de pêche, Muzeul National de Arta al României, Bucarest).

To capture the comings and goings of the boats and the strollers, Pissarro and Berthe Morisot preferred to make use of slightly plunging perspectives, from an elevated viewing point. Berthe was especially interested in the effects of perspective, which she skilfully mastered (L’Entrée du port de Cherbourg, Yale University Art Gallery), while Pissarro attempted to capture the passage of time and atmospheric variations, delivering a superb series of port views of Le Havre which form part of his artistic legacy (L’Anse des Pilotes et le briselames est, Le Havre, après-midi, temps ensoleillé, Musée d’art moderne André Malraux, Le Havre).

This sensitive, delicate art is completely removed from the vigorous representations—heralding the Expressionist and Fauvist movements—which Monet, at the beginning of his career, would produce of fishing boats moored in the port of Honfleur (Barques de pêche, collection particulière, et Bateaux de pêche, Muzeul National de Arta al României, Bucarest).

To capture the comings and goings of the boats and the strollers, Pissarro and Berthe Morisot preferred to make use of slightly plunging perspectives, from an elevated viewing point. Berthe was especially interested in the effects of perspective, which she skilfully mastered (L’Entrée du port de Cherbourg, Yale University Art Gallery), while Pissarro attempted to capture the passage of time and atmospheric variations, delivering a superb series of port views of Le Havre which form part of his artistic legacy (L’Anse des Pilotes et le briselames est, Le Havre, après-midi, temps ensoleillé, Musée d’art moderne André Malraux, Le Havre).

room

7

From

ports to cliffs - From Le Havre to Cherbourg

If

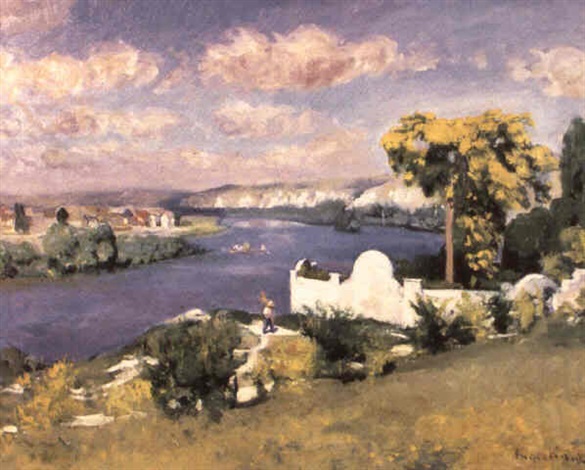

throughout the course of the 19thcentury, Rouen attracted so many landscape

painters from Turner, Boninton and Corot to Monet and Pissarro, it was because

of the town’s remarkable architectural heritage. Rouen was celebrated by Victor

Hugo as the ‘city of a hundred bell towers’ and was immortalized by Monet (La

Rue de l’Épicerie à Rouen, Collection particulière, courtesy of the Fondation

Pierre Gianadda, Martigny). The destination was made even more attractive due

to its topography, which Flaubert compared to an amphitheatre. Nestled between

the river and the surrounding hills, the town not only offered ‘the most

splendid landscape that a painter could ever dream of’ (Pissarro) but above all,

the effects of fog and rain and the constant atmospheric variations proved to

be a source of great pleasure to all those in search of the ephemeral. The

liveliness of the port and its industrial landscape, where the tall factory

chimneys on the left bank echoed the bell towers on the right bank, would draw

Pissarro to make this enthusiastic comparison: ‘It’s as beautiful as Venice’

(Le Pont Boieldieu, Rouen, effet de pluie, Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe,

room 7). Many of the Impressionist masters (Monet, Pissarro, Sisley, Gauguin)

would stay in Rouen. This, coupled with the presence of several important

collectors (François Depeaux, Léon Monet, Eugène Murer) would favour the birth

of a Rouen School to cite the expression of art critic, Arsène Alexandre. Monet

in Giverny Claude Monet lived for 43 years in his house in Giverny from 1883 to

1926. Passionate about gardening, he designed his gardens as veritable

paintings. In 1893, he put in a pond which he had covered with lily pads and

created a Japanese-style garden ‘for the pleasure of the eye but also with the

intention of providing subject matter for painting’. Until his death, his

garden proved to be his most fertile source of inspiration. Indeed, he once

said : ‘My most beautiful masterpiece is my garden’.

Monet began painting waterlilies in 1895 and his Japanese bridge would be the object of some fifty canvases. Taking out the horizon and the sky, he narrowed his focus on the bridge, the water and the reflections. From 1918 onwards, the pictorial elements or details would give way to an explosion of colours, with the density of the brushstrokes bordering on abstraction. The water and the sky seem to merge and under these fireworks of colour, the bridge appears little by little, providing a landmark or a point of reference to the composition.

As Daniel Wildenstein, author of the catalogue raisonné of the artist, would say, the exceptional series of the Pont japonaisrepresents the culmination of Monet’s oeuvre where the vibration of the colour is enough to evoke a world of sensation and powerful emotion

Monet began painting waterlilies in 1895 and his Japanese bridge would be the object of some fifty canvases. Taking out the horizon and the sky, he narrowed his focus on the bridge, the water and the reflections. From 1918 onwards, the pictorial elements or details would give way to an explosion of colours, with the density of the brushstrokes bordering on abstraction. The water and the sky seem to merge and under these fireworks of colour, the bridge appears little by little, providing a landmark or a point of reference to the composition.

As Daniel Wildenstein, author of the catalogue raisonné of the artist, would say, the exceptional series of the Pont japonaisrepresents the culmination of Monet’s oeuvre where the vibration of the colour is enough to evoke a world of sensation and powerful emotion

Room

8

If

throughout the course of the 19th century, Rouen attracted so many

landscape painters from Turner, Boninton and Corot to Monet and Pissarro, it

was because of the town’s remarkable architectural heritage. Rouen was

celebrated by Victor Hugo as the ‘city of a hundred bell towers’ and was

immortalized by Monet (La Rue de l’Épicerie à Rouen, Collection particulière,

courtesy of the Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Martigny). The destination was made

even more attractive due to its topography, which Flaubert compared to an

amphitheatre. Nestled between the river and the surrounding hills, the town not

only offered ‘the most splendid landscape that a painter could ever dream of’

(Pissarro) but above all, the effects of fog and rain and the constant

atmospheric variations proved to be a source of great pleasure to all those in

search of the ephemeral. The liveliness of the port and its industrial

landscape, where the tall factory chimneys on the left bank echoed the bell

towers on the right bank, would draw Pissarro to make this enthusiastic

comparison: ‘It’s as beautiful as Venice’ (Le Pont Boieldieu, Rouen, effet de

pluie, Staatliche Kunsthalle, Karlsruhe, room 7). Many of the Impressionist

masters (Monet, Pissarro, Sisley, Gauguin) would stay in Rouen. This, coupled with

the presence of several important collectors (François Depeaux, Léon Monet,

Eugène Murer) would favour the birth of a Rouen School to cite the expression

of art critic, Arsène Alexandre.

Monet in Giverny

Claude Monet lived for 43 years in his house in Giverny from 1883 to 1926. Passionate about gardening, he designed his gardens as veritable paintings. In 1893, he put in a pond that he had covered with lily pads and created a Japanese-style garden ‘for the pleasure of the eye but also with the intention of providing subject matter for painting’. Until his death, his garden proved to be his most fertile source of inspiration. Indeed, he once said: ‘My most beautiful masterpiece is my garden’. Monet began painting waterlilies in 1895 and his Japanese bridge would be the object of some fifty canvases. Taking out the horizon and the sky, he narrowed his focus on the bridge, the water and the reflections. From 1918 onwards, the pictorial elements or details would give way to an explosion of colours, with the density of the brushstrokes bordering on abstraction. The water and the sky seem to merge and under these fireworks of colour, the bridge appears little by little, providing a landmark or a point of reference to the composition.

Monet in Giverny

Claude Monet lived for 43 years in his house in Giverny from 1883 to 1926. Passionate about gardening, he designed his gardens as veritable paintings. In 1893, he put in a pond that he had covered with lily pads and created a Japanese-style garden ‘for the pleasure of the eye but also with the intention of providing subject matter for painting’. Until his death, his garden proved to be his most fertile source of inspiration. Indeed, he once said: ‘My most beautiful masterpiece is my garden’. Monet began painting waterlilies in 1895 and his Japanese bridge would be the object of some fifty canvases. Taking out the horizon and the sky, he narrowed his focus on the bridge, the water and the reflections. From 1918 onwards, the pictorial elements or details would give way to an explosion of colours, with the density of the brushstrokes bordering on abstraction. The water and the sky seem to merge and under these fireworks of colour, the bridge appears little by little, providing a landmark or a point of reference to the composition.

As

Daniel Wildenstein, author of the catalogue raisonné of the artist, would say,

the exceptional series of the Pont japonais represents the culmination of

Monet’s oeuvre where the vibration of the colour is enough to evoke a world of

sensation and powerful emotion (Pont

japonais, Collection Larock-Granoff, Paris).

Louis Anquetin (1861-1932) La Seine près de Rouen, 1892 79 x 69 cm, oil on canvas Collection particulière© Collection particulière / Tom Haartsen

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) Le Pont Boieldieu, Rouen, effet de pluie,1896 73 x 92 cm, oil on canvasKarlsruhe, Staatliche Kunsthalle© BPK, Berlin, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Image Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen

COMPLETE CREDITS

RENOIR Pierre-Auguste (1841-1919) La Côte près de Dieppe - 1879 - Oil on canvas - 49,5 x 60,6 cm Montclair, New Jersey, Kasser Mochary Foundation © Photo Tim Fuller © Kasser Mochary Foundation, Montclair, NJ

CAILLEBOTTE Gustave (1848-1894) Régates en mer à Trouville - 1884 - 60,3 x 73 cm - Oil on canvas - Toledo, Ohio. Lent by the Toledo Museum of Art. Gift of The Wildenstein Foundation © Photograph Incorporated, Toledo

MONET Claude (1840-1926) Etretat, la porte d’Aval, bateaux de pêche sortant du port - around 1885 - Oil on canvas - 60 x 80 cm - Dijon, Musée des Beaux-Arts © Musée des beaux-arts de Dijon. Photo François Jay

RENOIR Pierre-Auguste (1841-1919) La Cueillette des moules - 1879 - Oil on canvas - 54,2 x 65,4 cm - Washington D.C., National Gallery of Art. Gift of Margaret Seligman Lewisohn in memory of her husband, Sam A. Lewisohn © Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

GAUGUIN Paul (1848-1903) Le Port de Dieppe - around 1885 - Oil on canvas - 60,2 x 72,3 cm - Manchester, Royaume-Uni, Manchester City Galleries © Manchester Art Gallery, UK / Bridgeman Images

SIGNAC Paul (1863-1935) Port-en-Bessin. Le Catel - around 1884 - Oil on canvas - 45 x 65 - Collection particulière © Collection particulière

CALS Félix (1810-1880) Honfleur, Saint-Siméon -1879 - Oil on canvas - 35 x 54 cm - Caen, Association Peindre en Normandie © Association Peindre en Normandie

BOUDIN Eugène-Louis (1824-1898) Scène de plage à Trouville - 1869 - 28 x 40 cm - Oil on panel - Collection particulière. Courtesy Galerie de la Présidence, Paris © Galerie de la Présidence, Paris

MONET Claude (1840-1926) Camille sur la plage à Trouville - 1870 - Oil on canvas - 38,1 x 46,4 cm - New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, Collection of Mr. and Mrs John Hay Whitney, B.A. 1926, Hon. 1956 © Photo courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery

PISSARRO Camille (1830-1903) Avant-port de Dieppe, après-midi, soleil - 1902 - Oil on canvas - 53,5 x 65 cm Dieppe, Château-Musée © Ville de Dieppe - B. Legros

MONET Claude (1840-1926) L’Église de Varengeville à contre-jour - 1882 - Oil on canvas - 65 x 81,3 cm - Birmingham, The Henry Barber Trust, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham © The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham

BONINGTON Richard Parkes (1802-1828) Plage de sable en Normandie - around 1825-1826 - Oil on canvas - 38,7 × 54 cm - Trustees of the Cecil Higgins Art Gallery Bedford (The Higgins Bedford) © Trustees of the Cecil Higgins Art Gallery, Bedford

MONET Claude (1840-1926) Falaises à Varengeville also known as Petit-Ailly, Varengeville, plein soleil - 1897 - Oil on canvas - 64 x 91,5 cm - Le Havre, Musée d’art moderne André Malraux © MuMa Le Havre / Charles Maslard 2016

BOUDIN Eugène-Louis (1824-1898) Entrée du port du Havre par grand vent - 1889 - Oil on canvas - 46 x 55 cm - Collection particulière. Courtesy Galerie de la Présidence, Paris © Galerie de la Présidence

COURBET Gustave ( 1819-1877) La Plage à Trouville - around 1865 - Oil on canvas - 34 x 41 cm - Caen, Association Peindre en Normandie © Association Peindre en Normandie

MONET Claude (1840-1926) La Rue de l’Épicerie à Rouen - around 1892 - Oil on canvas - 93 x 53 cm - Collection particulière. Courtesy Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Martigny (Suisse) © Claude Mercier photographe

ANQUETIN Louis (1861-1932) La Seine près de Rouen - 1892 - Oil on canvas - 79 x 69 cm - Collection particulière © Collection particulière / Tom Haartsen

MORISOT Berthe (1841-1895) La Plage des Petites-Dalles - around 1873 - Oil on canvas - 24,1 x 50,2 cm Richmond, Virginie, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Collection