Through 30 December 2016

Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK

Dazzling

treasures combining gold and precious pigments-some of the finest illuminated

manuscripts in the world-are on display in celebration of the

Fitzwilliam Museum’s bicentenary.

The majority of the exhibits are from the

Museum’s own rich collections, and those from the founding bequest of Viscount

Fitzwilliam in 1816 can never leave the building and can only be seen at the Museum.

For the first time, the secrets of master illuminators and the sketches hidden

beneath the paintings are revealed in a major exhibition presenting new art

historical and scientific research.

Spanning the 8th to the 17th centuries, the 150 manuscripts and fragments in COLOUR: The Art andScience of Illuminated Manuscripts guide us on a journey through time, stopping at leading

artisticcentres of medieval and Renaissance Europe. Exhibits highlight the

incredible diversity of the Fitzwilliam’s collection: including local treasures,

such as the Macclesfield Psalter made in East Anglia c.1330-1340, a leaf

with a self-portrait made by the Oxford illuminator William de Brailes c.1230-1250, and a

medieval encyclopaedia made in Parisc.1414 for the Duke of Savoy.

Four years of cutting-edge

scientific analysis and discoveries made at the Fitzwilliam have traced the creative

process from the illuminators’ original ideas through their choice of pigments

and painting techniques to the completed masterpieces.

Detail: Jean Corbechon, Livre des proprietés des choses, Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, France, Paris, 1414, Master of the Mazarine Hours (act. c.1400-1415)

Leading artists of

the Middle Ages and early Renaissance did not think of art and science as

opposing disciplines,” says curator, Dr Stella Panayotova, Keeper of Manuscripts

and Printed Books. “Instead,drawing on diverse sources of knowledge, they

conducted experiments with materials and techniques to create beautiful works

that still fascinate us today.”

Merging art and science, COLOUR shares the

research of MINIARE (Manuscript Illumination: Non-Invasive Analysis, Research

and Expertise), an innovative project based at the Fitzwilliam. Collaborating with

scholars from the University of Cambridge and international experts, the

Museum’s curators,scientists and conservators have employed pioneering

analytical techniques to identify the materials and methods used by

illuminators.

A popular misconception is that all manuscripts were made by

monks and contained religious texts, but from the 11thcentury onwards professional scribes and artists were

increasingly involved in a thriving book trade, producing both religious and

secular texts. Scientific examination has revealed that illuminators sometimes

made use of materials associated with other media, such as egg yolk, which was

traditionally used as a binder by panel painters.

Other discoveries include

pigments rarely associated with manuscript illumination– such as the first ever

example of smalt detected in a Venetian manuscript. Smalt, obtained by grinding

blue glass, was found in a Venetian illumination book made c.1420. Evidently, the artist who painted it had close links with

the famed glassmakers of Murano. This example predates by half a century the

documented use of smalt in Venetian easel paintings.

Analyses of sketches lying

beneath the paint surfaces, and of later additions and changes to paintings help

to shed light on manuscripts and their owners. One French prayer book, made c.1430, was adapted over three generations to reflect the

personal circumstances and dynastic anxieties of a succession of aristocratic

women. Adam and Eve were originally shown naked in an ABC commissioned c.1505 by the French Queen,Anne of Brittany (1476-1514) for

her five-year-old daughter. However, a later owner, offended by the nudity, gave

Eve a veil and Adam a skirt. Infrared imaging techniques and mathematical

modelling have made it possible to reconstruct the original composition without

harming the manuscript.

The Museum’s treasures will be displayed alongside

carefully selected loans —celebrated manuscripts from Cambridge libraries as

well as other institutions in the UK and overseas. These include an 8th century Gospel Book from Corpus Christi College, the

University Library’s famous Life of Edward the Confessor, magnificent

Apocalypses from Trinity College and Lambeth Palace, London, and a unique model

book from Göttingen University.

Catalogue entries and

essays by leading experts offer readers insight into all aspects of colour from the

practical application of pigments to its symbolic meaning.

Detail:The Macclesfield Psalter

From The Arts Desk Ltd:

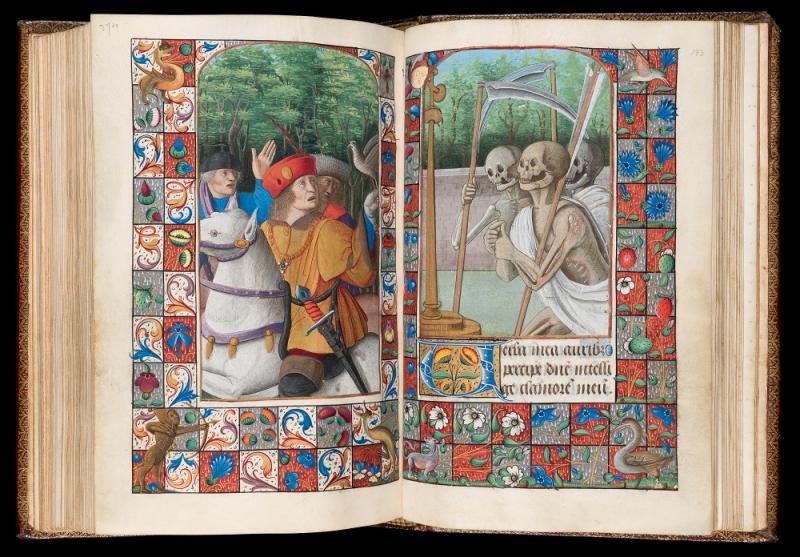

Book of Hours, Use of Rome, 'The Three Living and the Three Dead', Western France, c. 1490-1510All images © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Safely tucked away in libraries, illuminated manuscripts have survived in far greater numbers and, as such, form the most substantial, if most easily overlooked, legacy of medieval and Renaissance visual culture. The bland anonymity of a bound volume shelved amongst thousands was not much of a draw for the vandals and looters of the past, and served to shield the richly decorated pages from light and the elements.

Of the world’s many illuminated manuscript collections, that of the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge is reputedly the finest, the books cocooned in fenland isolation, the terms of the founder’s bequest ensuring that much of the collection remains forever inside the museum (pictured above: The Macclesfield Psalter, c.1330-1340).

In this spellbound state, the Fitzwilliam perpetuates the conditions that have kept these books safe for centuries, and the knowledge of this makes looking at them a strangely timeless experience. In galleries darkened to protect light-sensitive pigments, pages embellished with gold and silver leaf twinkle convincingly, just as they must have done when seen by candlelight...

In another beguiling example, an eagle marks the beginning of an eighth-century St John’s Gospel, the intricate but spare design with large areas of blank parchment typical of manuscripts made at Lindisfarne. We are told that the organic purple used to colour the eagle’s head is derived from a lichen found locally, over which yellow orpiment has been applied in dots. The contrast between the local purple, and the rare, imported yellow is evocative, and shows that for all its isolation Lindisfarne was part of an international trade network. But it also shows the technical expertise of the Lindisfarne illuminators, who knew that the organic purple base would prevent the deterioration of the orpiment, an unstable pigment that would otherwise tend to turn black....