October 9, 2016–January 16, 2017

International Gallery of Modern Art in Venice

February 2017

William Merritt Chase (1849–1916) was a brilliant colorist, inventive designer and engaging storyteller. Praised for his observations of contemporary life, he was a leading American Impressionist, influential teacher and prominent international figure at the turn of the 20th century. William Merritt Chase, the first retrospective of the artist’s career in more than three decades, features approximately 80 of Chase’s finest works in both oil and pastel, drawn from public and private collections across the US.

The show opens with a glimpse into the artist’s studio, which served as a stage for his imagination and became a colorful backdrop for many of his paintings. Thematic groupings in the galleries explore his range of subjects—from jewel-like landscapes and urban park scenes to portraits of modern women and shimmering still lifes. Examining all four decades of his career, the exhibition offers a fresh look at Chase’s role in shaping American modern art—not only as a charismatic mentor to thousands of students, including Georgia O’Keeffe, Edward Hopper and Joseph Stella, but also as a pioneering, cosmopolitan artist in his own day. As O’Keeffe later remarked, “there was something fresh and energetic and fierce and exacting about him that made him fun.”

The son of a shoe salesman in Indiana, Chase studied art in Europe and then centered his career in New York—although his first solo exhibition took place at the Boston Art Club in 1886. He worked from the 1870s into the 1910s, adapting Impressionism to depict modern American subjects and helping to elevate the status of American art on the world stage. A devoted father of eight, Chase taught throughout his life in order to support his large family. He offered classes in New York City in the winter and on Long Island in the summer, took students to Europe, and in 1896 opened the Chase School of Art, now the Parsons School of Design.

While Chase is less well-known than his contemporaries Mary Cassatt, John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler, his work and position at the heart of the American art world at the turn of the last century are gaining renewed attention from scholars and the public. William Merritt Chase was organized by four scholars of American art: Erica Hirshler, Croll Senior Curator of American Paintings at the MFA; Elsa Smithgall from The Phillips Collection; Katherine M. Bourgignon from the Terra Foundation of American Art; and Giovanna Ginex, an independent scholar for the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia.

“Chase became a champion both for American art and the art of his time,” said Hirshler. “But he believed that a painter should have great respect for the art of the past. Inspired by the old masters and excited by the beauty he found in the world around him, Chase created bold compositions of everyday subjects, family and friends.”

The exhibition opens with a key work,

Portrait (later titled The Young Orphan [An Idle Moment], 1884, National Academy Museum, New York), depicting a young girl seated in a red armchair against a red background. Chase sent it to the first exhibition of Les Vingt (The Twenty), an avant-garde group of Belgian artists, held in Brussels in 1884. He was one of only three American artists featured, alongside Whistler and Sargent. European critics praised Chase’s portrait, firmly establishing his place within the international art circle.

Studio as Theater

Chase turned his studio into a stage. From 1878 to 1895, he rented the two largest rooms in New York’s Tenth Street Studio Building, transforming them into one grand space used for both work and entertainment. He filled his studio with hundreds of objects from around the world—old master paintings, Japanese parasols, Renaissance furniture, Islamic lamps, fabrics, rustling chimes, great copper pots and dozens of exotic shoes. Assembled into harmonious arrangements, they appear as backdrops in more than a dozen interiors from the 1880s that showcase the artist’s glamorous and evocative space.

Chase’s studio scenes combine still life with real life. Fabrics and furnishings are depicted with great attention to texture and sheen, walls are crammed with paintings and porcelains, shelves are laden with miscellaneous ornaments. At times, unfinished pictures sit on easels and completed paintings in heavy gold frames rest on the floor. Sitters enliven these sets—often they are women, as seen in the canvases

Studio Interior (about 1882, Brooklyn Museum), in which a woman examines a book of prints, and

Tenth Street Studio (1880, Saint Louis Art Museum), where an elegantly dressed female figure reclines in a deep blue armchair. A dog sleeps on the rug below her, its paw resting on the train of her dress, while Chase himself appears in a shadowy corner of the composition, leaning forward to engage the woman in conversation.

Chase’s Self-Portrait (about 1883, An MFA Honorary Trustee and Her Spouse) is on view exclusively at the MFA. With the jaunty tilt of his head, palette in hand and a red note on his jacket, he refers to an old master he greatly admired, drawing inspiration from

Velázquez’s self-portrait in Las Meninas. Chase’s self-portrait, however, is rendered in pastel—a modern medium revived by avant-garde artists in the late 19th century. Considering pastel equal to oil, Chase co-founded the American Society of Painters in Pastel in 1882. The group’s monogram, stamped in red, can be seen in the upper right corner of the work.

The section also introduces Chase’s most frequent model—his wife Alice Gerson. Painted a year before their marriage in 1887,

Meditation (1886, Willard and Elizabeth Clark) is one of Chase’s most prized pastels. The portrait depicts Gerson in a hat, gloves and heavy jacket, holding a fur muff in her lap. Ready to go out, she has paused, losing herself in a moment of contemplation, chin in hand. Her eyes are fixed on the viewer and engage with the world—a recurring feature in Chase’s many depictions of modern women, who were reshaping society in the decades following the Civil War.

A European Education

Chase left his modest boyhood home in Indiana to study briefly in New York and then, in 1872, at the Royal Munich Academy. There, he developed a rich, dark and sculptural painting style and cultivated a lifelong passion for the old masters. With his portraits of modern women, however, Chase invented a genre for his own age.

At first sight, the MFA’s recently acquired Ready for the Ride (1877) recalls numerous portraits by Rembrandt, Hals, Rubens and Van Dyck. Painted in a three-quarter-length format with a restricted palette, the female subject is depicted in a Dutch-style tall hat and white collar. Two elements identify the work as a modern-day canvas: the woman’s straightforward gaze and the riding crop she holds. Her severely tailored dress and sturdy gloves are designed for riding sidesaddle in a fashion called en amazone—a reference to the legendary warrior horsewomen of Greek mythology. She glances back over her shoulder, ready to embark on an adventure. Marked by Chase as his “turning point,” Ready for the Ride was the first of the artist’s modern old masters to depict a new woman—a combination that would appear frequently throughout his career.

In 1877, Chase spent nine months in Venice with his American friends and fellow Munich students Frank Duveneck and John Twachtman. During the sojourn, Chase created at least 20 paintings and drawings, using a realist approach on a range of subjects. His scenes of Venice’s distinctive water-bound architecture and the riches of its fish markets are on view in the exhibition.

A Fish Market in Venice (The Yield of the Waters) (1878, Detroit Institute of the Arts) displays an uncompromising realism, seen especially in the gleaming texture of the fish. The original composition featured a fisherman unloading his basket, but Chase painted over the figure about a decade later, transforming the work into a pure still life—a format for which he became recognized and praised.

Modern Conditions

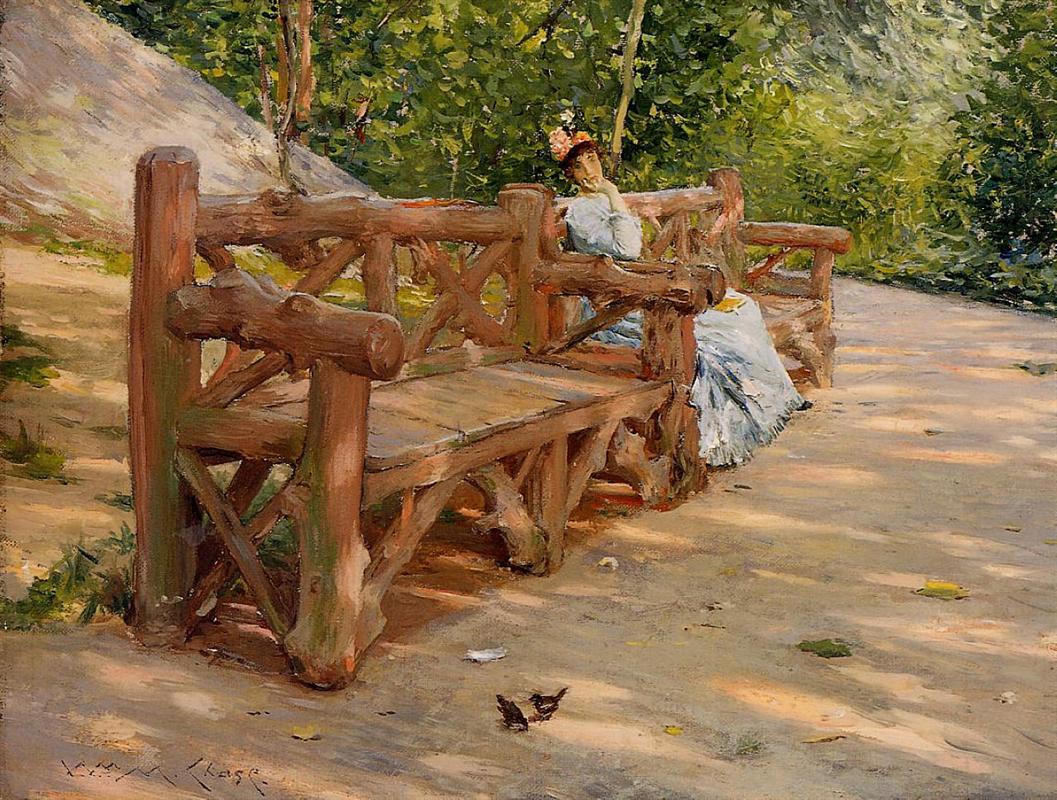

The 1880s marked transitions in Chase’s personal life, as well as a new direction in his art, with a move away from his dark Munich manner. After their marriage in 1887, Chase and his wife Alice moved in with his parents in Brooklyn and had their first child—Alice, nicknamed Cosy—the oldest of six daughters and two sons. The setting inspired new subject matter for Chase—the beauty of everyday life, depicted with an increasingly brighter color palette. Working en plein air, or outdoors, like the French Impressionists, Chase began to paint scenes of leisure in urban parks. A City Park (about 1887, Art Institute of Chicago) depicts a well-dressed young woman on a bench in Tompkins Park. Her features are blurred, perhaps in acknowledgement of contemporary etiquette that advised women never to catch the eye of a stranger in public places. Nevertheless, she is alert and facing the viewer—the model, like her setting, is modern.

The MFA’s Park Bench (about 1890) depicts another young woman, lost in thought in Central Park, her novel forgotten in her lap.

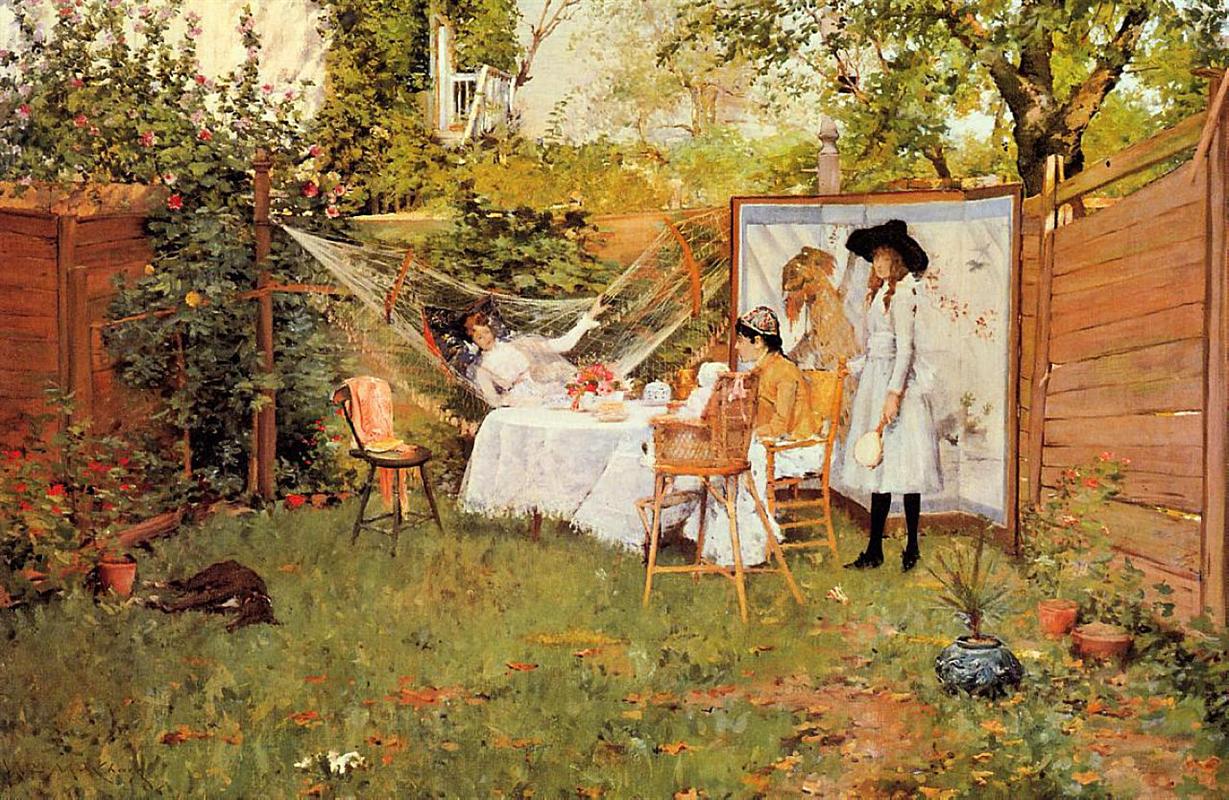

Chase also found new inspiration within his growing family.

The Open Air Breakfast (about 1888, Toledo Museum of Art) presents a scene of a casual morning meal in the garden of the extended Chase family home in Brooklyn. Alice tends to Cosy, seated in a high chair. Chase’s sister Hattie stands with a racquet, Alice’s sister Virginia lolls in a hammock, and Fly, the family greyhound, sleeps in the shade. The painting is a celebration of modern suburban leisure, rendered in a bright palette with a light touch.

Posing and Composing

Chase produced a large number of portraits throughout his career, in which he combined the lessons he learned from the old masters he admired with a distinctly new perspective. These works celebrate the forthright stance of modern women, experiment with color contrasts and harmonies, and showcase the artist’s great joy in the glistening properties of paint.

Chase’s most successful and compelling likenesses were not commissions, but portraits he solicited, intending to use them as entries in major exhibitions. His sitters were often his wife, friends, fellow artists or students.

Chase’s arresting Portrait of Dora Wheeler (1882–83, The Cleveland Museum of Art) depicts his first student, a painter and illustrator who studied with him in the late 1870s, in a meditative pose in her own studio. Wheeler’s blue dress is juxtaposed with the vibrant yellow of the embroidered Chinese (or Chinese-inspired) textile in the background.

Chase sent the painting to the prestigious Paris Salon in 1883, where it was shown with

Sargent’s The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (1882), now in the MFA’s collection and on view in the Art of the Americas Wing.

In 1885, Chase met and befriended Whistler while traveling in London. At Whistler’s suggestion, they painted each other’s portraits.

Chase’s James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1885, Metropolitan Museum of Art) captures the artist’s cultivated theatrical persona. Whistler was not amused—he called Chase’s painting a “monstrous lampoon” and broke off their friendship. Still, Chase greatly admired Whistler. After their meeting, he made a series of paintings of women in shimmering monochromatic color schemes that pay homage to Whistler’s aesthetic.

Others pay homage to the past—among them is Chase’s striking portrait of his student,

Lydia Field Emmet (1892, Brooklyn Museum), which presents her in a commanding pose often used in old master portraits of men, investing her with authority as she embarked on her own career.

Another large-scale work—Portrait of Mrs. C (Lady with a White Shawl) (1893, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts)—combines dark, rich colors with confident brushwork. It was described by Chase as his “greatest picture.”

Chase’s engagement with texture, sheen and arrangement of forms in space was not unique to his portraits of people. He explored the same qualities in his still lifes. This section features three of them, including the MFA’s

Still Life—Fish (about 1908), one of Chase’s most admired works and the first of his paintings to enter the Museum’s permanent collection.

Chase and Japonisme

Following the opening of trade between Japan and the West in the 1850s, a fad for all things Japanese swept both artistic circles and popular culture in Europe and the US—a movement referred to as japonisme. Japanese prints, ceramics, textiles, furniture and decorative arts flooded the Western market, intriguing artists and inspiring them to incorporate them into their work.

Chase’s studio was filled with a number of items from Japan: umbrellas, kimonos, fans, prints, books and costume dolls. Paintings featuring these objects not only highlight his penchant for accumulating an eclectic array of objects, but also reveal his fascination with Asian design.

The setting of A Comfortable Corner (about 1888, Parrish Art Museum) includes a Japanese screen and a large bronze vessel, along with Asian textiles. The model, wrapped in a blue kimono over Western petticoats, shoes and stockings, holds a fan and rests on a red Western-style divan. Chase uses the edges and borders of the rug, sofa and screen to provide an underlying geometrical structure to his composition. The pose of the model, the solidity of his forms and animation of his brushwork, however, prevent the composition from looking anything but Western.

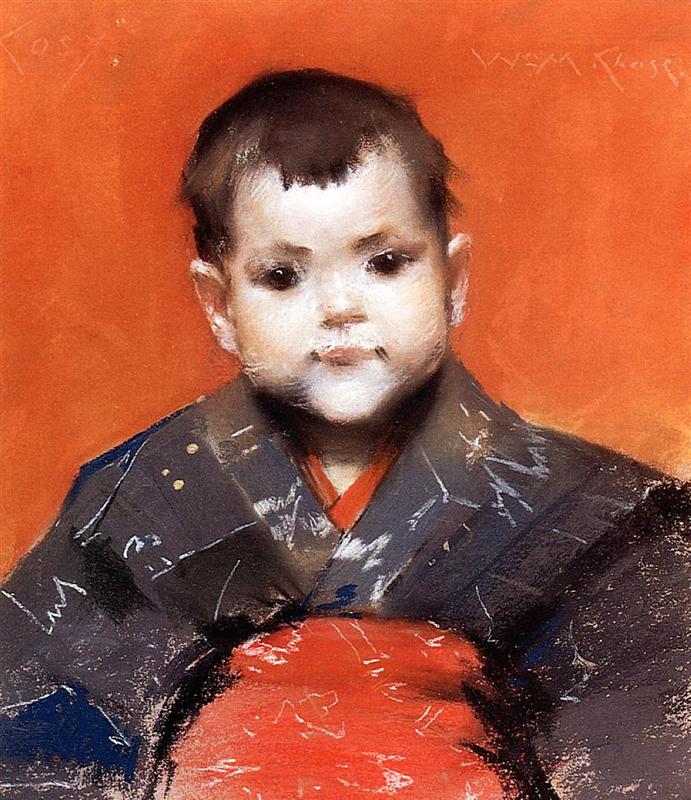

My Baby Cosy (1888, Private Collection) is a pastel that depicts Chase’s oldest daughter in a blue-gray garment, with a tightly wrapped red obi holding her in place like a swaddling band.

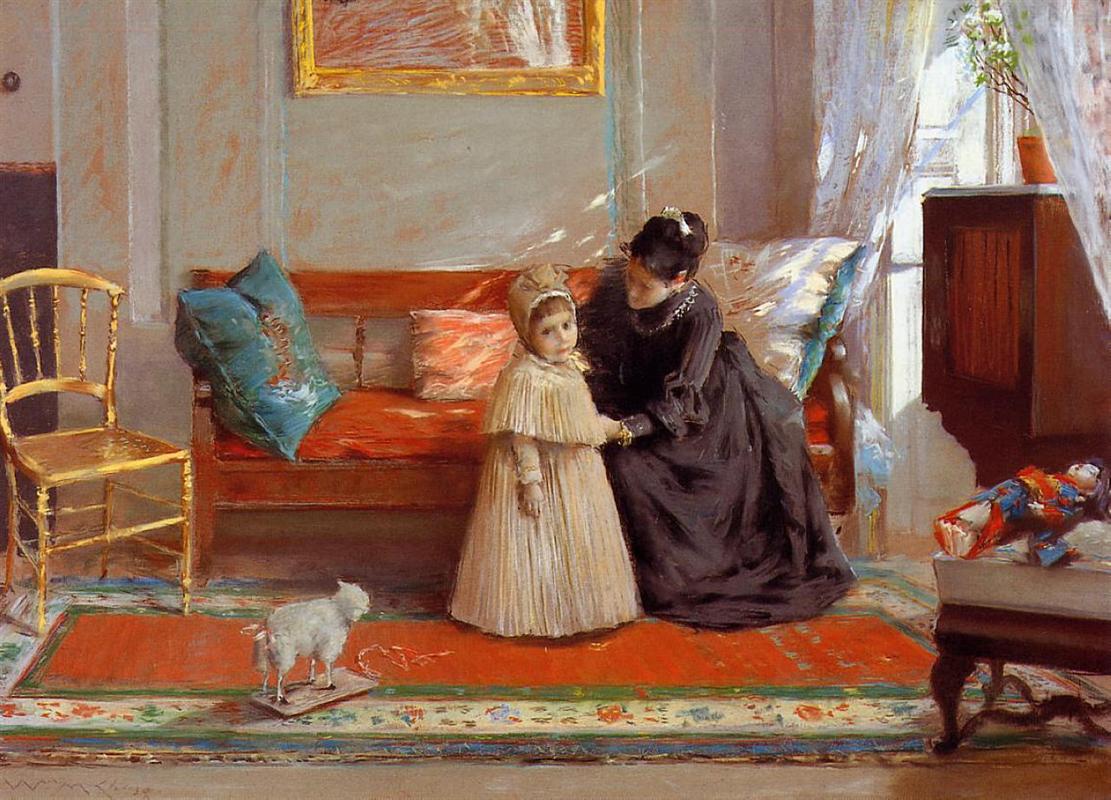

Cosy also appears in the full-length

Mother and Child (The First Portrait) (about 1888, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston)

and Shinnecock: Studio Interior (1892, Terra Foundation for American Art), where she examines a Japanese album on the floor of her father’s studio.

Chase’s interest in Japan was both aesthetic and personal—he deeply admired Japanese goods and in 1888, he named his second daughter Koto, after the Japanese painter Koto House, who had been one of his favorite students.

Art in the Open Air

From 1891 to 1902, Chase and his family spent summers at Shinnecock, on Long Island, where he was the founding director and star attraction of the Shinnecock Summer School of Art—the first American school devoted to plein air painting. He welcomed hundreds of students every summer, teaching two days a week and spending the rest of the time with his family and at his own work. The rural setting encouraged more casual pursuits—picking flowers, digging in the sand and collecting seashells—and Chase continued to celebrate leisure within his paintings.

Idle Hours (about 1894, Amon Carter Museum of American Art) encapsulates the joy of the family’s seaside summers, depicting Alice immersed in a book and one of the girls gazing up at the sky.

In The Big Bayberry Bush (about 1895, Parrish Art Museum), three of the girls—Cosy, Koto and Dorothy—are scattered in the wild grass and scrub surrounding their house, which appears in the distance. All of them wear white dresses, but their sashes, ribbons and stockings add notes of blue, yellow and red to the composition—their father plays with these primary colors just as his daughters play in the sandy dunes. Praised for their fresh depiction of light and cheerful subjects, the works—although not entirely Impressionist—point to Chase’s knowledge of European trends and desire to experiment with a brighter palette.

The Shinnecock Summer School of Art closed in 1902. Almost annually from 1903 until 1913, Chase organized summer classes in Europe, immersing himself and his students in old master paintings at museums, as well as contemporary art. Sunlit views of Florence and Venice from this period are featured.

Life in the Studio

Home and studio remained inseparable throughout Chase’s career. His famous space in the Tenth Street Studio Building had served as a place for work, sales and entertainment, but in 1895, Chase closed it and auctioned off the contents.

His later studios also served as family spaces. The lack of boundary between Chase’s public and private worlds is most evident in his home at Shinnecock. The house had a designated studio, but it also served as a living area where his wife and children could lounge and play.

The Ring Toss (about 1896, The Halff Collection) depicts an older Cosy taking the lead in an indoor game, ready to throw a rope ring around a standing pin, while her sisters Koto and Dorothy await their turn.

At times, the entire ground floor of the Shinnecock house became a temporary studio. The large pastel

Hall at Shinnecock (1892, Terra Foundation for American Art) captures Alice and two of the daughters in the elaborately decorated great hall. Chase’s own reflection can be seen in the mirrored black armoire. Alice appears in Chase’s Shinnecock studio in

For the Little One (about 1896, Metropolitan Museum of Art), a portrait of her sewing a long white garment for one of their children. The image, although modern in style, presents a comforting image of conventional family life—as does the double portrait

Mrs. Chase and Child (I’m Going to See Grandma) (about 1889, San Antonio Museum of Art), which shows Cosy wistfully turning away from play as Alice fusses over her two-year-old daughter’s coat.

Several solo portraits of Alice, created during their marriage, are featured.

An Artist’s Wife (1892, Private Collection) catches her studying one of her husband’s paintings. Alice appears in a Dutch costume, turning to look over the back of her chair. The conceit recalls 17th-century portraits by Frans Hals, although Hals most often used it for depictions of men.

Self-Portrait in 4th Avenue Studio (1915–16, Richmond Art Museum) is one of Chase’s last efforts. The artist shows himself at work, palette in hand. The canvas on his easel bears only the earliest traces—an enthusiastic nod to work yet to come.

Publications

An illustrated MFA Publications volume, William Merritt Chase, written by Erica Hirshler, Croll Senior Curator of American Paintings, provides a compact introduction to Chase’s paintings and pastels.

Hirshler also contributed to William Merritt Chase: A Modern Master, the fully illustrated exhibition catalogue published by Yale University Press in association with The Phillips Collection. The publication features essays by Hirsher and her co-curators Elsa Smithgall from The Phillips Collection; Katherine M. Bourguignon from the Terra Foundation of American Art; and Giovanna Ginex, an independent scholar for the Fondazione Musei Civici di Venezia. It also includes an essay by John Davis, the Terra Foundation’s Executive Director of Global Academic Programs; and a foreword by Frederick Baker, an expert on the artist and co-author of the Chase catalogue raisonné.

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)