From 15 June to 23 September 2018, the Musée Fabre de Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole will be presenting the Picasso – Donner à voir exhibition, in association with ‘Picasso-Méditerranée’, an international cultural event launched by the Musée National Picasso-Paris. Montpellier – a Mediterranean metropolis located halfway between Catalonia and Provence – is involved in this programme.

The Musée Fabre is presenting a major exhibition encompassing the artist’s entire career and offering an overview of the creation of a prodigious oeuvre with a particular focus in the selection and presentation of the works. The exhibition is structured around his pivotal years, experimentation and departures from previous work, reflecting the continuous movement of his metamorphoses. The works will be presented in an open-plan exhibition format that lends itself well to formal comparisons between periods.

Fourteen key dates

While the idea of change governs all of Picasso’s artistic creation, we can nevertheless identify certain paroxysmal moments.

The exhibition’s perspective is rooted in fourteen key dates that highlight formal and technical departures from Picasso’s oeuvre; yet it is also deliberately distanced from the artist’s biography. It covers 900 m 2 and is designed with no physical separation between the different sections, meaning the works can be compared, contrasted and viewed from different perspectives.

Each section brings together a variety of different works completed over a short time period: one or several seasons, a single year. The selected works thus reflect the artist’s ability to explore several formal hypotheses at the same time, sometimes even within the same work.

A ‘self-destructive’ artist

The open-plan format challenges the idea of ‘evolution’ in Picasso’s work and deconstructs any overly linear interpretation of his oeuvre. None of his departures are ever definitive. The physical changes in Picasso’s work reflect a series of round trips within his own career path.

While several recent exhibitions have helped highlight the external points of reference used or ‘cannibalised’ by the artist (Picasso and the Masters, Picasso and Folk Art and Traditions), Picasso – Donner à voir demonstrates how Picasso drew inspiration from his own work.

The exhibition explores the period from 1895 to 1972: 77 years of artistic creation!

In addition to masterpieces of painting, sculpture, etching and drawing, records, sketchbooks and preparatory drawings have been included that reveal these moments of intense experimentation and bring us closer to the creative process.

Musée Fabre will display over 120 pieces within the exhibition, including a remarkable set of works loaned by the Musée National Picasso-Paris, representing ‘all the breakthroughs, all the key pieces that Picasso kept to himself in order that he could continue living with them and seeking out what it was that his painting or sculpture had achieved at a given point – something that he would perhaps only understand much later, in the light of other works or in a different era’. (Pierre Daix).

These are joined by works on loan from other prestigious museums in France and elsewhere, including Picasso Museum Barcelona; Musée Picasso, Antibes; Kunsthaus Zurich; Museum Berggruen, Berlin; Metropolitan Museum, New York; National Gallery of Art, Washington; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Lyon; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Grenoble; Musée d’Orsay, Paris; Musée de l’Orangerie, Paris; Bibliothèque Nationale de France; Médiathèque Emile Zola de

![Image result for [[["xjs.sav.en_US.y5vqFNLwkD0.O",5]],[["id","type","created_timestamp","last_modified_timestamp","signed_redirect_url","dominant_color_rgb","tag_info","url","title","comment","snippet","image","thumbnail","num_ratings","avg_rating","page","job"]],[["dt_fav_images"]],10000]](https://pbs.twimg.com/media/DgroWPkXcAY8fx5.jpg)

Pablo Picasso, Vollard Suite: Faun Unveiling a Sleeping Girl (Jupiter and Antiope, after Rembrandt), 12 June 1936, sugar-lift aquatint with varnish, scraper and burin on copper. Sixth state, Montpellier, Musée Fabre, photo © Musée Fabre de Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole / Frédéric Jaulmes, press office / Musée Fabre, © Succession Picasso 2018

In its collection of graphic works, the Musée Fabre possesses a remarkable copy of the Vollard Suite (1930-1937) by Picasso, thanks to the generosity of Frédéric Sabatier d’Espeyran. The diplomat and bibliophile donated his entire library to the city of Montpellier in 1965, all in all over 600 publications and albums illustrated by the greatest artists of the 20 th century. (Two years later, his wife, née Renée de Cabrières, donated the private mansion which today houses the Musée Fabre’s decorative arts department.) Thanks to this remarkable legacy, now shared between the Médiathèque Emile Zola and the Musée Fabre, the museum is one of the rare establishments in the world to hold a complete, signed copy of the Vollard Suite .

The Sabatier d’Espeyran collection contains other engravings and lithographs by Picasso, including another series also published by Ambroise Vollard, Les Saltimbanques , as well as more recent illustrated books, such as Toros and Les Bleus de Barcelone , published for the opening of the Picasso Museum in Barcelona.

The exhibition Picasso, Donner à voir will be a rare opportunity for the Musée Fabre to showcase the Vollard Suite in its entirety, as part of its permanent collection. A selection of other engravings, publications (mostly from the Sabatier d’Espeyran collection housed in the Médiathèque Zola) and copper plates will also be on display to evoke the artist’s studio, opposite a presentation about the donor.

The

exhibition is structured around fourteen key dates, pivotal moments in

Picasso’s career.

SECTION I – 1895-1896: ON THE ROAD AGAIN

The exhibition opens with the itinerant nature of Pablo Ruiz Picasso’s life, which took him from LaCorogne to Barcelona, via Madrid and Malaga. This travel with his family was motivated by his father’s appointment as a teacher at the school of fine arts in Barcelona.

The moving around is presented as a metaphor for the numerous shifts and transformations between styles and techniques practised by the artist throughout his life.A series of academic works allude to Picasso’s traditional training at the LaCorogne school followed by the prestigious LaLlotja school in Barcelona.

In parallel, two more personal paintings reflect Picasso’s early artistic maturity and his mastery of the conventions of the Spanish realist tradition:

Portrait of a Young Girl, Barefoot (early 1895, LaCorogne) and Self-portrait (1896)

SECTION II – 1901: PARISIAN MODERNITY AND THE BLUE PERIOD

Picasso visited Paris for the first time in 1900 for the Exposition Universelle, the world’s fair where he had the opportunity to see the most recent artworks produced by the Parisian avant-garde, completing the survey opened up to him by Catalan modernism. He moved to Madrid in spring 1901 where he was appointed artistic director of the Arte Joven review that reflected the artist’s ambition, namely to import Catalan and Parisian modernism to the city.

Picasso then returned to Paris, where art dealer Ambroise Vollard dedicated a solo exhibition to the artist. This proved to be an occasion for Picasso to demonstrate his ability to assimilate the vocabulary of modernism. In the run-up to this exhibition, he was invited to exhibit in a collective exhibition in France for the first time, organised by the Société des Beaux-Arts de Béziers.Picasso’s enthusiastic response to the City of Lights and the distractions it offered was somewhat overshadowed, however, by the suicide, just months later, of his close friend Carlos Casagemas.

The colourful exuberance of his earlier paintings was replaced by an ethereal monochrome tone that faithfully represented feelings of misery. Pierre Daix described the shift as ex abruptoor ‘violent’.

SECTION III – 1906: ARCADIA AND ARCHAISMP.

Picasso’s search for exoticism was sparked by his discovery, on the one hand, of

The Turkish Bath, a painting by Ingres, in autumn 1905 and, on the other hand, of Gustave Fayet’s collection, which included several works by Gauguin, in 1906.

With these indirect allusions and through the mediation of works by other artists, frequent exchanges with André Derain and Henri Matisse prompted Picasso to familiarise himself with ‘Negro art’, a term which encompassed all art produced outside of Europe. Picasso’s trip to Gósol, a village in the Catalan Pyrenees, in the summer of 1906, resulted in the artist’s combining of exoticism and archaism. He drew inspiration from traditional mountain costumes and attitudes as well as Romanesque sculpture. He modified his vocabulary in light of a stricter repertoire seemingly drawn from an imaginary Arcadia.

William Rubin identified this moment with ‘the shift from gentle lyricism to a hardening of shapes and a more sculptural precision of forms.’ This section will include an ensemble of paintings and sculptures in which these different concerns were manifested in the theme of the woman at her dressing table: between eroticism mixed with exoticism and dreams of a primitive society.

SECTION IV – 1907-1908: SPOTLIGHT ON LES DEMOISELLES D’AVIGNON

Inspired by his first visit to the Musée du Trocadero in spring 1907 and his rivalry with Derain and Matisse, Picasso undertook an ambitious painting project that would pass into posterity under the name Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Picasso produced a substantial volume of preparatory works which gave the artist the time to plan for every aspect of a complex composition, the final outcome clearly a direct result of the thoroughness of his preceding studies.

This intense period of research in spring is examined by presenting notebooks and sketches, drawings and painted studies rounded out by a multimedia installation which lends a tangibility to the creative process at work.The final piece in this section, Three Figures Under a Tree, painted in winter 1907, provides some understanding of the connection between the ‘geometric monstrosity’ (André Salmon) of

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and cubism.

SECTION V – 1911-1912: CUBISMS

Man with a Guitar (autumn 1911) and Still Life with Chair Caning (spring 1912) are two masterpieces that provide a window into the ‘mountain rope’ that tied Picasso and Georges Braque, whom the artist met in 1907, together. The two founders of cubism then explored different methods, not for representation but the suggestion of reality. The image, firstly fragmented almost to the point of abstraction, was then recomposed using new processes, like the introduction of printed block letters to the composition and collages with motifs (e.g. chair caning, newspaper and wallpaper) produced in series.

At the same time as Still Life with Chair Caning opened the way to papier colléand prefigured the question of theready-made, the work also heralded a method that would prove fundamental in the next stages of Picasso’s artistic practice: the association of different forms of representation in a single work.

SECTION VI – 1914: ‘BAROQUE CUBISM’ AND A NEW INGRISM

The summer of 1914 was a pivotal moment in Picasso’s career. He initially continued exploring the potential afforded by cubism with the association of several geometric or other naturalistic elements in the same work, or indeed the representation of a single subject in several compositions in visual registers that at first glance seemed conflicting.

His Man Leaning on a Table series helps us to understand this process.The reappearance of Ingres-style drawing in the artist’s work suggests neither a rupture nor a ‘return to order’ but rather the introduction of an additional element that allowed the artist to play with forms of representation and the evocation of reality. This approach finds its iconographic equivalent in the omnipresent theme of the six-sided dice. The pointillist technique also re-emerged, echoing Picasso’s experimentations during the years 1900 and 1901. Picasso then drew subtly on all the registers he invented or made his own.

From 1914 emerged a double movement in his creative process: he further enriched the range of pictorial options available to him at the same time as he borrowed, self-referenced, subverted and combined others.1914 was also the year in which Picasso, a Spanish artist, was separated from his French friends who were either sent to the front line like Braque and Derain, or enlisted voluntarily like Apollinaire. The gallery owned by his art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler was also confiscated.

SECTION I – 1895-1896: ON THE ROAD AGAIN

Picasso, Self-portrait, 1896 Oil on canvas, 32 x 23.5 cm. Barcelona, Musée Picasso © Succession Picasso 2018

The exhibition opens with the itinerant nature of Pablo Ruiz Picasso’s life, which took him from LaCorogne to Barcelona, via Madrid and Malaga. This travel with his family was motivated by his father’s appointment as a teacher at the school of fine arts in Barcelona.

The moving around is presented as a metaphor for the numerous shifts and transformations between styles and techniques practised by the artist throughout his life.A series of academic works allude to Picasso’s traditional training at the LaCorogne school followed by the prestigious LaLlotja school in Barcelona.

In parallel, two more personal paintings reflect Picasso’s early artistic maturity and his mastery of the conventions of the Spanish realist tradition:

Portrait of a Young Girl, Barefoot (early 1895, LaCorogne) and Self-portrait (1896)

SECTION II – 1901: PARISIAN MODERNITY AND THE BLUE PERIOD

Picasso, The Death of Casagemas, summer 1901, Oil on wood, 27 x 35, Musée national Picasso-Paris © Succession Picasso 2018

Picasso visited Paris for the first time in 1900 for the Exposition Universelle, the world’s fair where he had the opportunity to see the most recent artworks produced by the Parisian avant-garde, completing the survey opened up to him by Catalan modernism. He moved to Madrid in spring 1901 where he was appointed artistic director of the Arte Joven review that reflected the artist’s ambition, namely to import Catalan and Parisian modernism to the city.

Picasso then returned to Paris, where art dealer Ambroise Vollard dedicated a solo exhibition to the artist. This proved to be an occasion for Picasso to demonstrate his ability to assimilate the vocabulary of modernism. In the run-up to this exhibition, he was invited to exhibit in a collective exhibition in France for the first time, organised by the Société des Beaux-Arts de Béziers.Picasso’s enthusiastic response to the City of Lights and the distractions it offered was somewhat overshadowed, however, by the suicide, just months later, of his close friend Carlos Casagemas.

The colourful exuberance of his earlier paintings was replaced by an ethereal monochrome tone that faithfully represented feelings of misery. Pierre Daix described the shift as ex abruptoor ‘violent’.

SECTION III – 1906: ARCADIA AND ARCHAISMP.

Picasso, Woman with Comb, 1906, gouache on paper, 139 x 57, Paris, Musée de L’Orangerie© Succession Picasso 2018

Picasso’s search for exoticism was sparked by his discovery, on the one hand, of

The Turkish Bath, a painting by Ingres, in autumn 1905 and, on the other hand, of Gustave Fayet’s collection, which included several works by Gauguin, in 1906.

With these indirect allusions and through the mediation of works by other artists, frequent exchanges with André Derain and Henri Matisse prompted Picasso to familiarise himself with ‘Negro art’, a term which encompassed all art produced outside of Europe. Picasso’s trip to Gósol, a village in the Catalan Pyrenees, in the summer of 1906, resulted in the artist’s combining of exoticism and archaism. He drew inspiration from traditional mountain costumes and attitudes as well as Romanesque sculpture. He modified his vocabulary in light of a stricter repertoire seemingly drawn from an imaginary Arcadia.

William Rubin identified this moment with ‘the shift from gentle lyricism to a hardening of shapes and a more sculptural precision of forms.’ This section will include an ensemble of paintings and sculptures in which these different concerns were manifested in the theme of the woman at her dressing table: between eroticism mixed with exoticism and dreams of a primitive society.

SECTION IV – 1907-1908: SPOTLIGHT ON LES DEMOISELLES D’AVIGNON

Picasso, Three Figures Under a Tree, winter 1907-8, oil on canvas, 99 x 99, Musée National Picasso-Paris © Succession Picasso 2018

Inspired by his first visit to the Musée du Trocadero in spring 1907 and his rivalry with Derain and Matisse, Picasso undertook an ambitious painting project that would pass into posterity under the name Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Picasso produced a substantial volume of preparatory works which gave the artist the time to plan for every aspect of a complex composition, the final outcome clearly a direct result of the thoroughness of his preceding studies.

This intense period of research in spring is examined by presenting notebooks and sketches, drawings and painted studies rounded out by a multimedia installation which lends a tangibility to the creative process at work.The final piece in this section, Three Figures Under a Tree, painted in winter 1907, provides some understanding of the connection between the ‘geometric monstrosity’ (André Salmon) of

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and cubism.

SECTION V – 1911-1912: CUBISMS

P. Picasso, Still Life with Chair Caning, spring 1912, Oil and oilcloth on canvas framed with rope, 29 x 37, Musée National Picasso-Paris© Succession Picasso 2018

Man with a Guitar (autumn 1911) and Still Life with Chair Caning (spring 1912) are two masterpieces that provide a window into the ‘mountain rope’ that tied Picasso and Georges Braque, whom the artist met in 1907, together. The two founders of cubism then explored different methods, not for representation but the suggestion of reality. The image, firstly fragmented almost to the point of abstraction, was then recomposed using new processes, like the introduction of printed block letters to the composition and collages with motifs (e.g. chair caning, newspaper and wallpaper) produced in series.

At the same time as Still Life with Chair Caning opened the way to papier colléand prefigured the question of theready-made, the work also heralded a method that would prove fundamental in the next stages of Picasso’s artistic practice: the association of different forms of representation in a single work.

SECTION VI – 1914: ‘BAROQUE CUBISM’ AND A NEW INGRISM

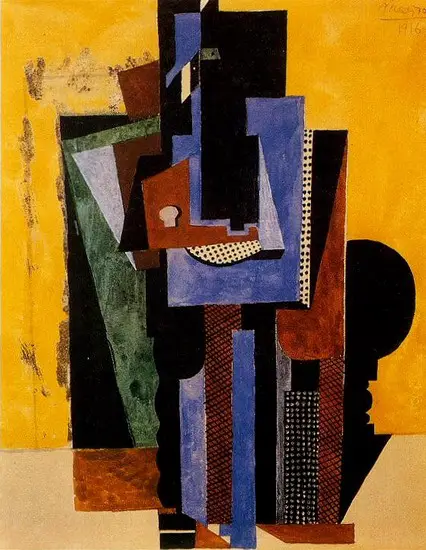

The summer of 1914 was a pivotal moment in Picasso’s career. He initially continued exploring the potential afforded by cubism with the association of several geometric or other naturalistic elements in the same work, or indeed the representation of a single subject in several compositions in visual registers that at first glance seemed conflicting.

Pablo Picasso. Man leans on a table, 1915

Pablo Picasso. Man leans hands CROSS has table, 1916

His Man Leaning on a Table series helps us to understand this process.The reappearance of Ingres-style drawing in the artist’s work suggests neither a rupture nor a ‘return to order’ but rather the introduction of an additional element that allowed the artist to play with forms of representation and the evocation of reality. This approach finds its iconographic equivalent in the omnipresent theme of the six-sided dice. The pointillist technique also re-emerged, echoing Picasso’s experimentations during the years 1900 and 1901. Picasso then drew subtly on all the registers he invented or made his own.

From 1914 emerged a double movement in his creative process: he further enriched the range of pictorial options available to him at the same time as he borrowed, self-referenced, subverted and combined others.1914 was also the year in which Picasso, a Spanish artist, was separated from his French friends who were either sent to the front line like Braque and Derain, or enlisted voluntarily like Apollinaire. The gallery owned by his art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler was also confiscated.

SECTION VII – 1918-1923: A BULIMIA OF STYLES

The Pipes of Pan, 1923, oil on canvas, MP79,Musée National Picasso-Paris © RMN-Grand Palais / Jean-Gilles Berizzi © Succession Picasso 2018

In this section, we take the year 1917 as the starting point to describe the method employed by Picasso which seems to have taken shape from this moment: metamorphosis versus evolution (Jean Leymarie).

The year 1917 was firstly one of new discoveries: Italy – Rome for the classical tradition and Naples and Pompeii for Antiquity – as well as his collaboration with the Ballets Russes company which introduced Picasso to an art from anchored in the present. Indeed, it was the present that governed all of the artist's choices, as he himself declared in an interview with Mexican critic Marius de Zayas in 1923. The notion of the present allowed Picasso to banish any idea of progress from his work.

In 1917, he demonstrated his freedom from any evolutionist interpretation of his work by reviving themes and processes seen more than a decade earlier during a trip to Barcelona where he depicted bullfights and women in traditional dress sometimes represented in the pointillist style. The figure of Harlequin that re-emerged in 1915 adopted new metaphorical significance: ‘While Harlequin was diversity personified, Picasso considered himself, after Rome, as painting personified.’ (Yve-Alain Bois).

This opinion confounds the idea that Picasso’s career was punctuated by a series of departures from his previous work. Thus, instead of focusing on a single year for this section, the collection presented is less restricted by time, between 1917 – the year when Picasso discovered Italy for the first time and returned to his Spanish roots – and 1923 when Picasso told Marius de Zayas: ‘The different techniques I have used in my art must not be considered as an evolution, or as steps toward an unknown ideal of painting. All I have ever made was made for the present and with the hope that it will always remain in the present.’

SECTION VIII – 1924-1930: ‘SURREALISMS’

Picasso, Head of a Man,1930, iron, brass and bronze, 83.5 x 40 x 36, Musée National Picasso-Paris © Succession Picasso 2018

The appearance of aggressive figures in Picasso’s works from 1924 interrupted the apparent tranquillity that set the tone during the course of preceding years in which his painting was inhabited by harlequins and giants. This was the year in which André Breton published his surrealist manifesto, stating: ‘Picasso is hunting in the environs.’

Picasso’s rapprochement with the surrealist group was confirmed the following year when the artist agreed to have studies he created in the summer of 1924 in Juan-les-Pins reproduced in reviews La Révolution Surréaliste(issue 2) and later La Danse (issue 4).

Picasso also participated in the first surrealist exhibition at the Pierre gallery in Paris. Later, in 1928, he became close with sculptor Julio Gonzalez who introduced him to the soldering technique that allowed Picasso to pursue his destruction/recomposition of the human figure by creating anthropomorphic sculptures with everyday objects, a technique not dissimilar to surrealist processes

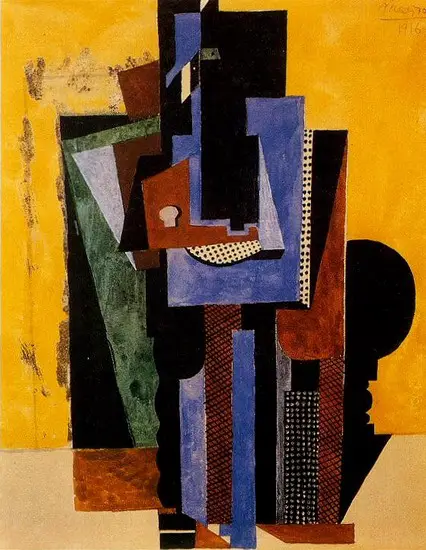

Picasso, Painter Picking up his Brush, 1927, etching, 46 x 50, illustration for H. de Balzac, Le Chef-d’œuvre inconnu, Paris, Vollard, 1931© Succession Picasso 2018

Picasso’s renewed interest in sculpture prompted by his meeting Gonzalez flourished in June 1930 when he purchased the Château de Boisgeloup which he converted into a spacious studio. Concurrently, Picasso signed up to several ambitious editorial projects which gave him the opportunity to step up his engraving work.

In autumn 1930, Albert Skira commissioned Picasso to produce a suite to illustrate Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The book was published in October 1931 with 32 etchings. The diversity of the styles employed, at times in the same plate, was a direct echo of the theme of Metamorphoses. The same year, Ambroise Vollard published Le Chef d’œuvre inconnu (The Unknown Masterpiece) by Balzac, which featured engravings on wood based on drawings by Picasso.

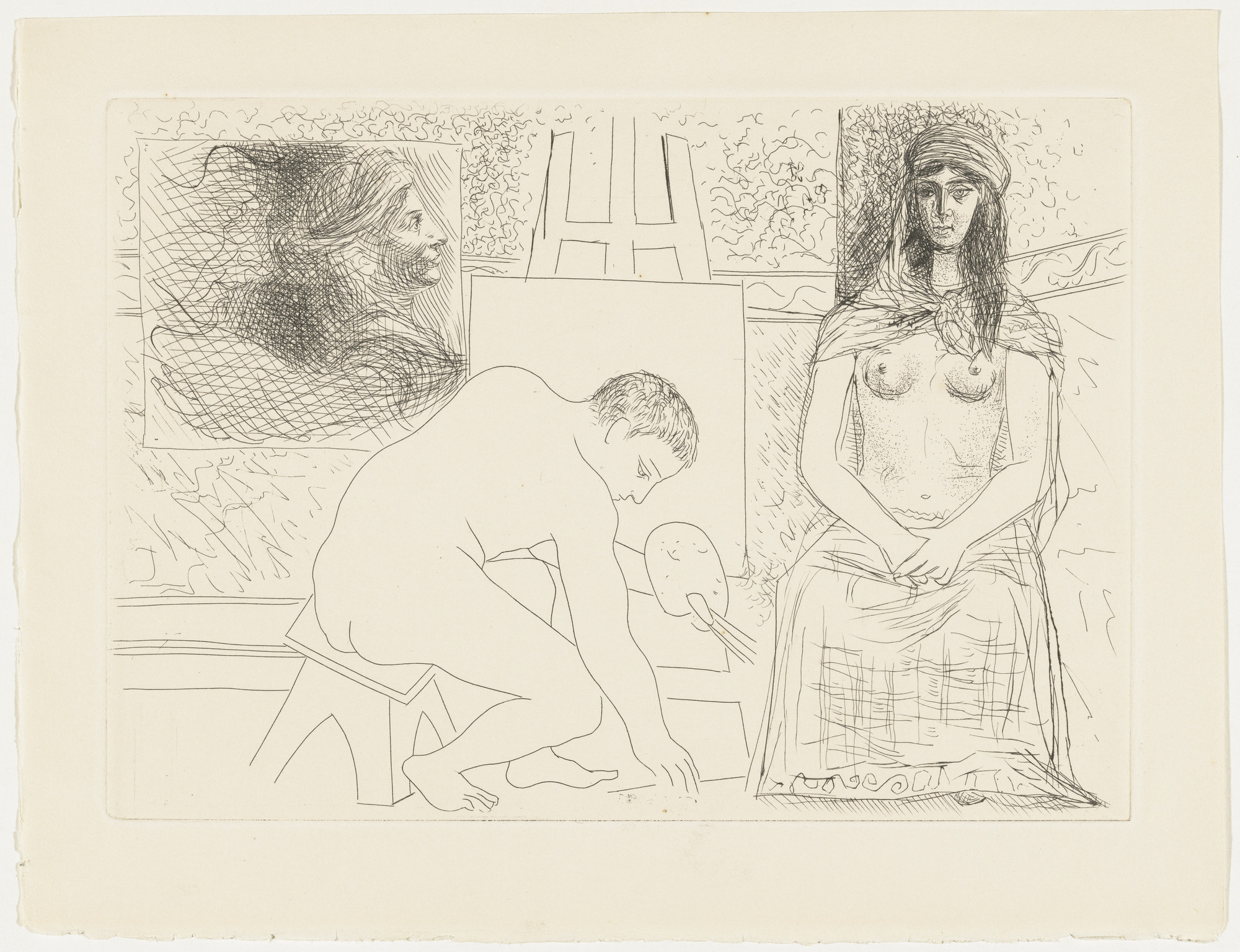

SECTION X – 1937: SPOTLIGHT ON GUERNICA

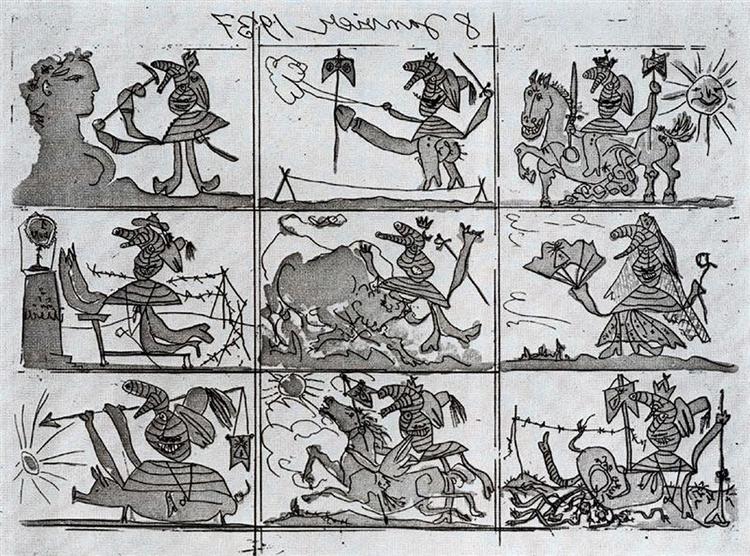

P. Picasso, Dream and Lie of Franco, 1937, etching and sugar-lift aquatint on copper, 31.7 x 42.2 cm Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France© Succession Picasso 2018

The beginning of 1937 was marked by the eruption of politics at the heart of Picasso’s work. In January, he received a commission from the Spanish government for the country’s pavilion at the Exposition Internationale in Paris. The bombing of the city of Guernica on 28 April prompted Picasso to completely change the theme of his project which he had begun with a series of studies on the theme ‘The Studio: the painter and model’.

However, the coexistence of the intimate register of studio scenes and the representation of the miseries of war becomes striking from January. To show this, the Portrait of Marie-Thérèse– produced on 6 January – is presented beside the two prints forming the Dream and Lie of Franco, engraved on 8 January and whose theme was inspired by the events of the bombardment of Madrid. The contrast between the curves and pastel colours of the portrait and the parodic and monstrous register of the engravings echoes something Picasso said to Marius de Zayas in 1937: ‘If the subjects I want to express happen to lend themselves to different forms of expression, I never hesitate to adopt them.’

This combination of new elements and the re-use of other, older elements is characteristic of the way in which Picasso worked. Furthermore, the very theme of the publication reflected Picasso’s approach: the relentless attitude of the artist Frenhofer who modified over a decade the same composition, in permanent metamorphosis. The conclusion of the book, in which the ideal model seems to defeat the painter, echoes the Picassian iconography of the painter and his model. Sometimes the model is the object of the painter's gaze and desire, other times it takes its revenge and turns into a menacing figure.

Such as the case in Woman Throwing a Stone, which appears to aim at the painter/sculptor his tools or even a fragment of his own unstructured body.

The copies of Metamorphoses and Chef d’œuvre in connu presented in the exhibition come from the collection owned by Frédéric Sabatier, a collector and bibliophile from Montpellier, who will feature in a display structured around the copy of the Vollard Suite which he bequeathed to the city of Montpellier, currently held at the Musée Fabre.

SECTION XI – 1946-1947: THE MEDITERRANEAN REDISCOVERED

![Image result for [[["xjs.sav.en_US.sjmJ-Qqmk9Q.O",5]],[["id","type","created_timestamp","last_modified_timestamp","signed_redirect_url","dominant_color_rgb","tag_info","url","title","comment","snippet","image","thumbnail","num_ratings","avg_rating","page","job"]],[["dt_fav_images"]],10000]](http://museefabre.montpellier3m.fr/var/storage/images/media/images/expositions/2018_picasso_-_donner_a_voir/taureau_debout/99075-1-fre-FR/Taureau_debout.jpg)

Picasso, Bull, faience, 37 x 40 x 30, Antibes, Musée Picasso© Succession Picasso 2018

In the autumn of 1946, the curator of Château Grimaldi in Antibes invited Picasso to set up there to work with Françoise Gilot. Picasso, who was first introduced to this area on the Côte d’Azur in 1920, had spoken of the imaginary bond he felt united the port of Antibes and the evocation of Antiquity. During his stay he produced a considerable number of works that ‘reflected the classic Mediterranean tradition in a new vision, at once childlike and complex.’ (Roland Penrose). This revival was an opportunity to ‘bequeath a sort of anthology of the latest problems he had encountered, through a hymn to Françoise who changed his life.’ (Pierre Daix)

While Picasso revived certain visual statements and a Mediterranean iconography and geography, he also reappropriated two techniques he had not used for several years. In 1945, he met printer Fernand Mourlot and took up lithography again. During the summer of 1946, he met Georges and Suzanne Ramié who worked at the Madoura pottery in Vallauris, which signalled the start of a long collaboration from the following summer.

SECTION XII – 1953-1954: FROM INTIMATE CHRONICLES TO PAINTING PAINTINGS

Verve, cover by P. Picasso, 1953, Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale de France© Succession Picasso 2018

Late 1953 was described by Marie-Laure Bernadac as the pivotal episode that set the artist’s late period in motion. The moment was characterised by an urgency to paint and a period of hyper-production during which Picasso increased his experimentation. This section focuses on three groups in which the notion of metamorphosis is central. In drawings from the series inspired by the painter and his model published in the magazine Verve. Picasso once again reinvented the theme of the artist’s studio through representations in various styles.

Next, the series on Women of Algiers opened a succession of citations and variations inspired by paintings by the masters. Picasso then worked in series mode, seeming to explore each composition through multiple interpretations: ‘What interests him is what happens from one version to another, the changes, the metamorphoses, the toing and froing, the constants. “You understand”, he said to Kahnweiler, “it’s not about time regained, but time for discovery”.’ (Marie-Laure Bernadac).

The progression of a subject through time and space depicted across multiple representations is envisaged alternatively in three dimensions with his first sculptures made from folded sheet metal. The staccato succession of planes infers a new relationship with the space, about which Werner Spies remarked that there is ‘something dramatic in this impossibility to grasp and comprehend, yet at the same time we can see this art’s underlying rule, its variability and refusal to set the expression in stone and see the formal solutions as optimal and definitive.’

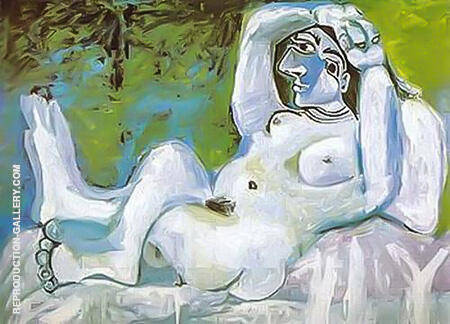

SECTION XIII – 1963-1964: ‘PAINTING IS STRONGER THAN ME’

P. Picasso, Large Nude, 1964, oil on canvas, 140 x 195, Zürich Kunsthaus© Succession Picasso 2018‘By painting paintings, and paintings of paintings (Delacroix, Velázquez and Manet) and by going through his ritual (of painter and model), Picasso ended up inventing an “alternative” way of painting, creating a new pictorial language.’ (Marie Laure Bernadac). From 1963 onwards, his painting only seemed to refer to itself, Picasso abandoning all direct citations of the compositions of the masters, iconography being supplanted by the pictorial. His frantic creativity can thus be gauged from the hundreds of paintings produced during his last ten years, which appears in an increasingly elliptical style.

Marie-Laure Bernadac spoke of his ‘stenographic style’ or even ‘painting/composition made of signs and ideograms’. Picasso learned in 1963 of the death of two friends from his early days, André Derain and Jean Cocteau, and his painting was fuelled by an urgency, the kind that threatens those who find themselves alone.

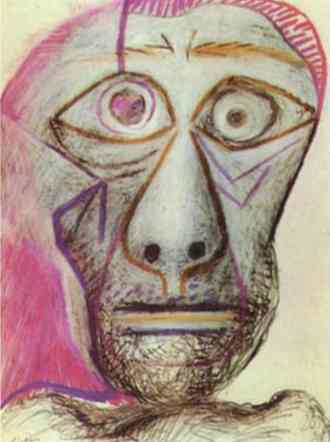

SECTION XIV – 1972: ‘MEMORIES OF THE PRANKS OF YOUTH’

Similar to the story about the painter Frenhofer about whom Picasso illustrated the short story Le Chef-d'œuvre inconnu, the artist’s career shows a trajectory forever unfinished, always recommencing. While Frenhofer destroyed his composition by producing a ‘wall of paint’ thereby drowning his subject, Picasso rather took the opposite approach: the figures he painted in the year before his death gradually dissolved into the white canvas.

Pierre Daix said as much talking about a painting from 1971: ‘Picasso broke his own painting and all painting to find a painting beyond painting. He recommenced what he had already done well between 1906 and 1908 or after 1924-1926, but now kicking every ounce of life out of his art, like a young painter dead set on expelling life from his painting.’

Picasso, The Young Painter, 1972, oil on canvas, 91 x 72.5, Musée National Picasso-Paris© Succession Picasso 2018

The exhibition concludes with the figure of the Young Painter showing the surprising portrait executed in 1972. This self-portrait, as guessed by René Char, indicates the youthfulness still driving Picasso in his final metamorphosis.

This is also the case of many skeletal self-portraits produced that same year, one of which Picasso spoke about to Pierre Daix: ‘I did a drawing yesterday. I think I have touched on something there... It’s not like anything ever done.’