Birmingham Museum of Art

November 20, 2020 - February 07, 2021

Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle features the series of paintings Struggle . . . From the History of the American People (1954–56) by the iconic American modernist. The exhibition reunites the multi-paneled work for the first time in more than half a century.

One of the greatest narrative artists of the twentieth century, Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000) painted his Struggle series to show how women and people of color helped shape the founding of our nation. Originally conceived as a series of sixty paintings, spanning subjects from the American Revolution to World War I, Struggle was intended to depict, in the artist’s words, “the struggles of a people to create a nation and their attempt to build a democracy.” Lawrence planned to publish his ambitious project in book form. In the end, he completed thirty panels representing historical moments from 1775 through 1817—from Patrick Henry to Westward Expansion. The 12- x 16-inch panels that comprise Struggle feature the words and actions of not only early American politicians but also of enslaved people, women, and Native Americans to address the diverse but mutually linked fortunes of all American constituencies engaged in the struggle. Taken as a whole, this remarkable series of paintings interprets and expresses the democratic debates that defined early America and still resonate today.

:focal(908x668:909x669)/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/af/f6/aff670aa-4763-4ace-aa1f-bd6568dd3b83/presspanel81800_002a.jpg)

Between 1949 and 1954, Jacob Lawrence made countless trips from his home in Brooklyn to the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library, where he scoured history books, letters, military reports and other documents for hidden stories that had shaped American history. By this point in time, Lawrence was “the most celebrated African American painter in America,” having risen to fame in the 1940s with multiple acclaimed series depicting black historical figures, the Great Migration and everyday life in Harlem. In May 1954, just as the Supreme Court ruled to desegregate public schools, the artist finally finished his research. He was ready to paint.

\According to Nancy Kenney of the Art Newspaper, Lawrence’s series was purchased privately in 1959 and later sold off “piecemeal.” The whereabouts of five of the paintings are unknown, and several others were deemed too delicate to travel; they are represented by reproductions.

Though the collection is incomplete, the new show offers a sweeping look at Lawrence’s remarkably human exploration of the country’s formative years.

“These are history paintings like you have never seen before,” says Lydia Gordon, PEM’s associate curator for exhibitions and research, in a museum blog post.

The series blends the boundaries between figuration and abstraction, and as its name suggests, struggle is a central theme. Lawrence’s scenes are angular and tension-filled, with thin lines of blood often dripping from characters. His interpretation of George Washington crossing the Delaware does not show the general standing majestically at the helm of a boat, as seen in Emanuel Leutze’s famed painting of the same subject. Instead, Lawrence’s preoccupation is with the nameless soldiers who fought and died for American independence. Here, these figures are shown huddled and cloaked, their bayonets jutting over the river like spikes.

Another one of Lawrence’s central concerns was the role of African Americans in the nation’s founding.

“[T]he part the Negro has played in all these events has been greatly overlooked,” he once said, as quoted by Sebastian Smee of the Washington Post. “I intend to bring it out.”

One panel depicts Patrick Henry’s famed 1775 call to arms against the British. The artwork is captioned with a line from Henry’s speech: “Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery?”

Still, the Patriots’ fight against bondage failed to encompass the country’s actual enslaved individuals. Yet another panel in the series shows African Americans in the throes of revolt.

“We have no property! We have no wives! No children! We have no city! No country!” reads the caption, which quotes a letter by Felix Holbrook, a slave who petitioned for emancipation in 1773.

Struggle also highlights the enslaved men, Creole people, and immigrants who fought with Governor Andrew Jackson in the 1815 Battle of New Orleans; the anonymous laborers who toiled to build the Erie Canal across New York state; and the contributions of Margaret Cochran Corbin, who followed her husband into the Revolutionary War and, when he was killed, took over firing his cannon. She became the first woman to receive a military pension—one that was “half the size of the men’s,” according to the museum. In Lawrence’s panel, Corbin is turned away from the viewer, a pistol tucked into the waistband of her dress.

The year he started painting Struggle, Lawrence explained that his objective for the series was to “depict the struggles of a people to create a nation and their attempt to build a democracy.” He painted these works during the modern Civil Rights era, knowing the battle was still not finished. Today, says Gordon, Struggle continues to resonate.

“[Lawrence’s] art,” she adds, “has the power to encourage difficult conversations that we need to be having: What is the cost of democracy for all?”

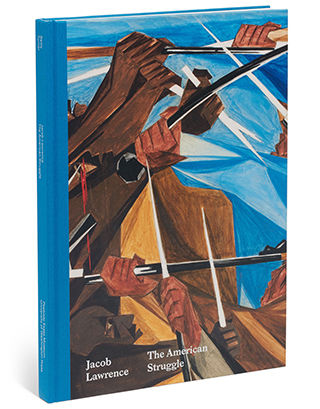

Exhibition Catalogue

This multi-authored volume, featuring contributions by contemporary art historians, cultural historians, and artists, examines Lawrence's epic American history series in diverse contexts that resonate profoundly today.

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/8f/dc/8fdc0c21-0aba-40a0-a040-7abf57215012/blogjlawsus1800_003.jpg)

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/71/8a/718a4b1f-7c0e-4179-b472-1f9a456a2a9e/exjlsli003.jpg)