The Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University

Jan. 26 to July 10, 2022

seeks to address this and related questions as it considers the long history of American artistic engagement with anti-Black violence. From the anti-lynching campaigns of the 1890s to the founding of Black Lives Matter in 2013 and up to today, (2)

seeks to address this and related questions as it considers the long history of American artistic engagement with anti-Black violence. From the anti-lynching campaigns of the 1890s to the founding of Black Lives Matter in 2013 and up to today, (2)

“How can art history help inform our understanding of the deep roots of racial violence?” asks curator Janet Dees. A new exhibition debuting later this month at The Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art at Northwestern University seeks to address this and related questions as it considers the long history of American artistic engagement with anti-Black violence. From the anti-lynching campaigns of the 1890s to the founding of Black Lives Matter in 2013 and up to today, A Site of Struggle: American Art against Anti-Black Violence (Jan. 26 to July 10, 2022) evokes the unbroken history of violence against African Americans in the United States and highlights African Americans as active shapers of visual discourse. Organized by The Block, the exhibition includes approximately 65 works of art and ephemera on loan from private and public collections across the country. With an emphasis on how art has been used to protest, process, mourn and memorialize anti-Black violence, A Site of Struggle stakes a claim on the power of the visual to make change.

“From realism to abstraction, from direct to more subtle approaches, American artists have developed a century of tools and creative strategies to stand against enduring images of African American suffering and death,” said exhibition curator Dees. “Contemporary artists taking on this subject are doing so within a long and rich history of American art and visual culture that has sought to contend with the realities of anti-Black violence.”

The Block Museum of Art has achieved national acclaim for curating groundbreaking traveling exhibitions and authoring scholarly publications that focus on crucial but understudied art histories and ask audiences to rethink assumptions about whose and what stories are told. A Site of Struggle builds on this legacy and The Block’s commitment to developing new scholarship in the field of American art.

“The Block Museum of Art is committed to developing bold, meaningful and challenging projects that ask audiences to reconsider accepted narratives and search for new modes of understanding and active reflection,” said Lisa Corrin, The Block Museum Ellen Philips Katz director. “In its breadth of scholarly and community collaborations and support of the museum’s ongoing social justice initiatives, A Site of Struggle is one of the most important exhibitions the institution has ever undertaken.”

The Evanston and Chicago areas are sites of several current ant-violence movements and a hub of historical African American activism and cultural production. The narrative of A Site of Struggle intersects with these efforts and histories in important ways. For example, Chicago was the home of Ida B. Wells (1862-1931), an anti-lynching activist and one of the founders of the NAACP, whose 1895 pamphlet A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Cause of Lynching in the United States 1892-1893-1894 influenced one of the exhibition’s key themes.

Five years in the planning, A Site of Struggle was developed from the perspective that anti-Black violence is not a new subject in American art. The exhibition and related publication are in part inspired by the recurrence of the phrase “a site of struggle” in Courtney R. Baker’s Humane Insight: Looking at Images of African American Suffering and Death (2015) and Leigh Raiford’s Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle (2011).

The exhibition is divided into three sections that are organized thematically around different artistic approaches, visual strategies and lines of inquiry across time periods.

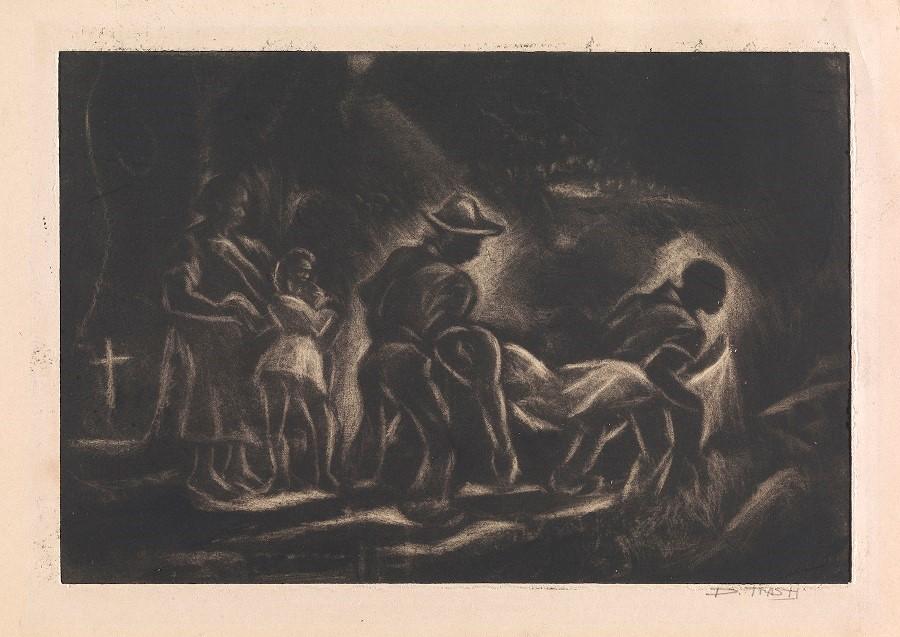

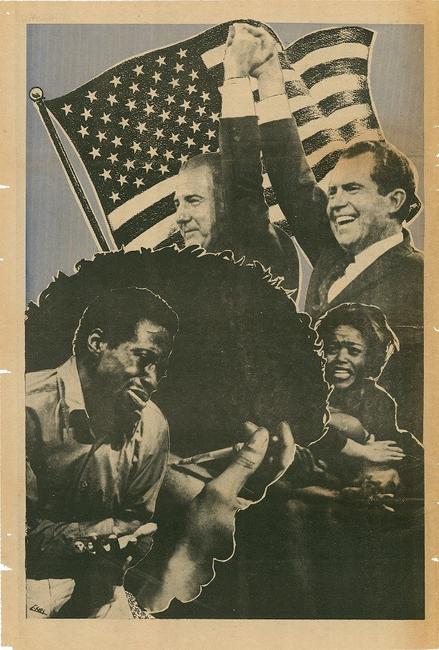

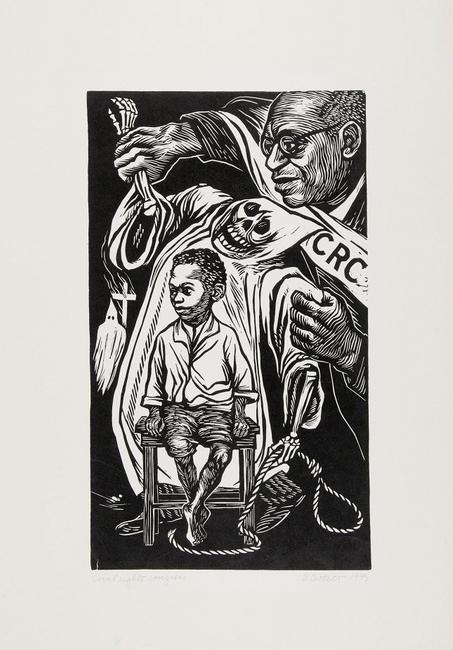

A Red Record explores how graphic depictions of violence were enlisted as a form of protest and awareness raising. Works such as George Wesley Bellows’ lithograph The Law Is Too Slow (1923), Norman Lewis’ watercolor Untitled (Police Beating) (1943) and Accused/Blowtorch/Padlock (1986) by Pat Ward Williams represent the horrors and implications of anti-Black violence.

In Abstraction and Affect artists employ conceptual strategies and varying degrees of abstraction to avoid literal representation of violence. Examples include Christian Marclay’s 2000 video Guitar Drag, informed by the dragging death of James Byrd, Jr. in 1998; Theaster Gates’ decommissioned firehoses (Minority Majority of 2012), which have been used as weapons against civil rights protesters; and Paul Rucker’s Soundless series (2015) of sculpted wood forms that serve as racial violence memorials.

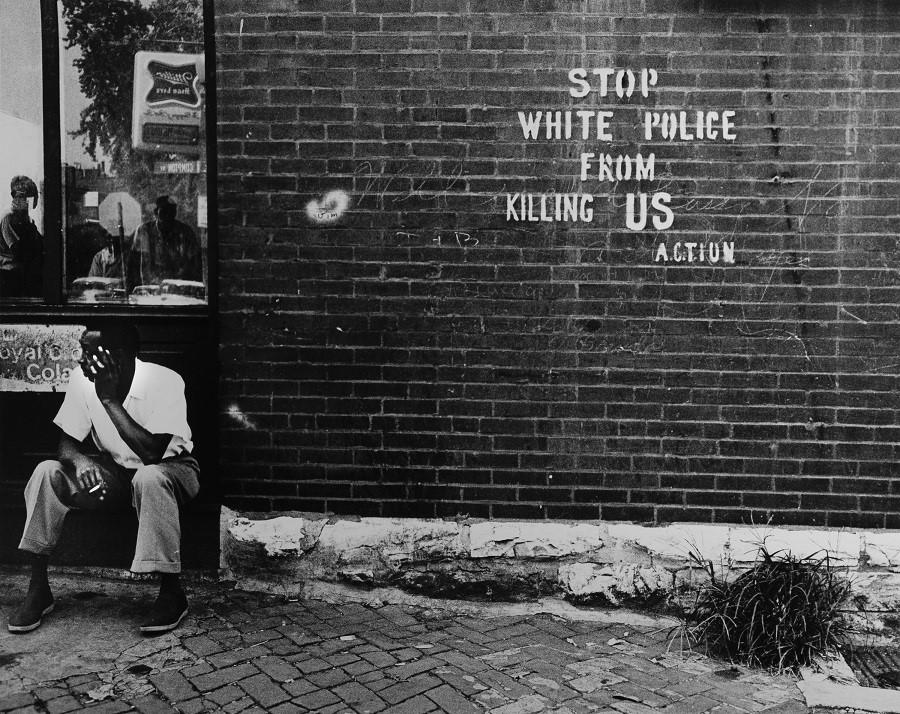

Written on the Body explores subtler allusions to and forms of violence, such as psychological impacts of racism, through engagement with the body. An anchor in this final section of the exhibition is Carl and Karen Pope’s body art video work Palimpsest (1998-99), which consists of edited footage of three permanent modifications that the artist Carl Pope made to his body. Other works featured here are Darryl Cowherd’s photograph Stop White Police from Killing Us-St. Louis, MO (c. 1966-67) and Untitled (Two Necklines) (1989), Lorna Simpson’s evocative text and photograph juxtaposition.

While the exhibition does not directly address recent acts of anti-Black violence of the last eight years and the impactful art made in response, the current climate informs the exhibition’s presentation and the resources provided to visitors. Through the examination of different artistic strategies and visual choices artists and activists have used to contend with this violence over a 100+ year period of American art, the project provides deeper context for contemporary debates and current movements for justice.

The artists whose works are included in A Site of Struggle are Laylah Ali (American, b.1968), George Wesley Bellows (American, 1882-1925), George Biddle (American 1885-1973), Elizabeth Catlett (American, 1915-2012), Darryl Cowherd (American, b. 1940), Bob Crawford (American, 1938-2015), Ernest Crichlow (American, 1914-2005), David Antonio Cruz (American, b. 1974), Emory Douglas (American, b. 1943), Melvin Edwards (American, b. 1937), Theaster Gates (American, b. 1973), Ken Gonzales-Day (American, b. 1964), Wilmer Jennings (American, 1910-1990), Norman Lewis, (American, 1909-1979), Christian Marclay (American, b. 1955), Kerry James Marshall (American, b. 1955), Isamu Noguchi (American, 1904-1988), Mendi + Keith Obadike (American, b. 1973), Howardena Pindell (American b. 1943), Carl and Karen Pope (American, b. 1961), Walter Quirt (American, 1902-1968), Paul Rucker (American, b. 1968), Lorna Simpson (American, b. 1960), Dox Thrash (American, 1893-1965), Molly Jae Vaughan (British, b. 1977), Lynd Ward (American, 1905–1985), Pat Ward Williams (American, b. 1948), Carrie Mae Weems (American, b. 1953), Ida B. Wells (American, 1862-1931), Walter White (American, 1893-1955) and Hale Woodruff (American, 1900-1980).

After its premiere at The Block, the exhibition will appear at the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts in Montgomery, Alabama, from Aug. 12 through Nov. 6, 2022. Montgomery is an important city in the history of the battle for African American civil rights in the United States, and includes many important landmark institutions such as Martin Luther King’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. It is the home of the Equal Justice Initiative’s Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which memorializes thousands of lynchings that occurred across the U.S.