For the first time in the Baltimore Museum of Art’s (BMA) history, the people who protect the art have selected the art. Guarding the Art, an exhibition curated entirely by 17 current and former members of the museum’s security team, opens on Sunday, March 27, with approximately 25 works of art from across the BMA’s collection.

The exhibition highlights the unique perspectives of the officers and their reflections on the featured objects are drawn from their many hours in the galleries, their interactions with visitors, and their personal stories and interests. Works by Jeremy Alden, Louise Bourgeois, Sam Gilliam, Grace Hartigan, Winslow Homer, Alma W. Thomas, Mickalene Thomas, and unidentified artists from Colombia, Costa Rica, and the Solomon Islands are among those featured in the exhibition. Guarding the Art is on view through July 10, and includes a fully illustrated catalogue.

The project was conceived last year by BMA Trustee Amy Elias as the result of a conversation with Dr. Asma Naeem, BMA Eddie C. and C. Sylvia Brown Chief Curator, about ways to engage with the security guards who spend more time with the museum’s collection than anyone else. Following that initial conversation, Elias continued to think about this challenge and then presented her concept of Guarding the Art to BMA leadership who wholeheartedly embraced the idea.

“Guarding the Art is more personal than typical museum shows as it gives visitors a unique opportunity to see, listen and learn the personal histories and motivations of guest curators,” said Elias. “In this way, the exhibition opens a door for how a visitor might feel about the art, rather than just providing a framework for how to think about the art.”

The project began with an inquiry sent to all members of the BMA’s security team gauging their interest in developing an exhibition that would provide them with an opportunity to have their voices heard through their perspectives about the museum’s collection. Seventeen members of the BMA signed on as guest curators and have worked over the past year in collaboration with museum leadership and staff to engage in every facet of exhibition development. The guest curators include Traci Archable-Frederick, Jess Bither, Ben Bjork, Ricardo Castro, Melissa Clasing, Bret Click, Alex Dicken, Kellen Johnson, Michael Jones, Rob Kempton, Chris Koo, Alex Lei, Dominic Mallari, Dereck Mangus, Sara Ruark, Joan Smith, and Elise Tensley. Renowned art historian and curator Dr. Lowery Stokes Sims provided additional mentorship and professional development guidance. Along with the creative opportunity, each participant was compensated for their time with funds directed from a lead grant from the Pearlstone Family Foundation.

For many of the guest curators, selecting the objects for the exhibition was the most challenging aspect of this project. After proposing up to three top choices, the group met with curators, conservators, and exhibition designers to learn more about each work, its condition, and presentation requirements. They debated several variations of the gallery floor plan and made final selections based on how well the works would fit in the spaces. Once that was completed, work on writing the object labels and producing content for the publication began. The team also met with education team members to develop public programs and marketing team members to discuss graphic identity, social media, and communications. All of their work, which continues through the July 10 closing of the exhibition, was coordinated by Sarah Cho, BMA Curatorial Assistant for American Painting & Sculpture and Decorative Arts, and Katie Cooke, BMA Curatorial Assistant to the Chief Curator and the Curatorial Division.

“There is so much more to see in the BMA’s collection than what’s on the gallery walls. It’s been exciting to get first-hand experience in organizing an exhibition and discovering all the behind-the-scenes considerations. It gives you a new respect for how museums work and the stories they tell,” said Elise Tensley. “I cannot wait to see all the objects we’ve selected on display.”

Exhibition

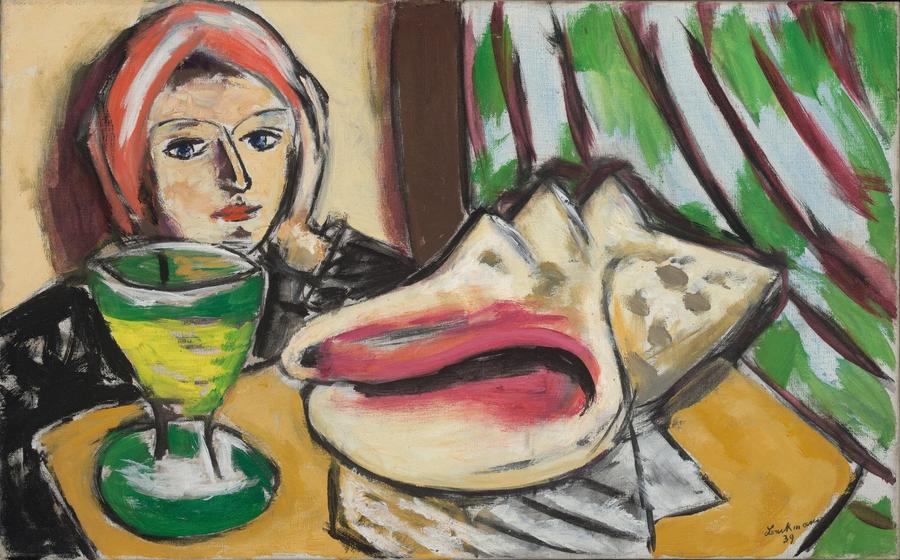

Guarding the Art reflects a broad range of backgrounds and interests with officers who are also artists, chefs, musicians, scholars, and writers. Kellen Johnson selected two works that have a connection to music and Black artists, respectively: Max Beckmann’s Still Life with Large Shell (1939), a portrait of his wife, Mathilde, who was a violinist and singer, and Hale Woodruff’s Normandy Landscape (1928), created when the artist was living in France. Joan Smith appreciates objects that are both functional and beautiful and chose a Water Bottle (Early 20th century) by an unidentified Mono artist in the Solomon Islands and a Bottleneck Basket (c.1875) by an unidentified Yokuts artist in California. Ben Bjork brings attention to the humor in art with Jeremy Alden’s 50 Dozen (2005/2008)—a chair composed entirely of Ticonderoga pencils that would break if sat upon—and British designer James Hadley’s satirical porcelain Teapot (1882).

Several objects were selected because of the time the officers spent regarding the works in the galleries. Dominic Mallari chose Sam Gilliam’s Blue Edge (1971), a powerful painting with bursts of color that evoke rings of noise and the sound of music he likens to “a melodic mess, like hearing the instrumental battles of musicians,” and Alfred Dehodencq’s Little Girl (c. 1850), which he admires for its combination of innocence and spunk. Bret Click enjoys interacting with visitors and invites them to find specific details in Entry into the Ark (c. 1575–1580), a grand painting attributed to Jacopo Bassano with assistance of Leandro and Francesco Bassano. Michael Jones designed a special case for Émile Antoine Bourdelle’s Head of Medusa (Door Knocker) (1925), so that he could finally experience the object without worrying about it being touched by visitors.

In some cases, the exhibition brings forward objects and artists that are overlooked or underrepresented. These include the House of Frederick Crey (1830-35) attributed to Thomas Ruckle, which provides an early glimpse of Baltimore’s Mt. Vernon neighborhood where Dereck Mangus lives, and Winslow Homer’s Waiting an Answer (1872), which Alex Lei admitted was one he didn’t notice until he stopped moving. “It’s strangely reflective of the experience of being a guard—a job mostly made up of waiting.” Elise Tensley focused on women artists and selected Winter’s End (1958) by Jane Frank, an abstract painting by a Baltimore-based artist that hasn’t been on view since 1983. Ricardo Castro’s desire to see more works by Latinx artists prompted his choice of a Seated Male Figure (500-1000) by an unidentified Quimbaya artist in Colombia, an Effigy Vessel of Standing Dignitary (500 BCE-CE 500) by an unidentified Jama-Coaque artist in Ecuador, and a Figure of a Shaman (Sukia) (1000-1520) from an unidentified Atlantic Watershed artist in Costa Rica. He also advocated for an empty plinth with an image of the Puerto Rican flag to represent the absence of works from his heritage.

One of the most admired artists is Grace Hartigan, whose Pallas Athena—Fire (1961) attracted Jess Bither with its swirling colors of potential energy, considered by many to be a self-portrait of the artist. She was also drawn to the mysterious melancholy aura of Louise Bourgeois’s sculpture Spring (1948-49/1984). Rob Kempton was inspired by passion, defiance, and revelation in Hartigan’s painting Interior, (The Creeks) (1957). He also chose Alma W. Thomas’s Evening Glow (1972), a painting he describes as a celebration of color and nature that gave him a deep calmness the first time he saw it. Chris Koo selected Philip Guston’s The Oracle (1974), which inspires him to create art with freedom and honesty rather than the approval of others. He also chose Mark Rothko’s Black over Reds [Black on Red] (1957) as a moment for meditation.

Several guest curators are interested in works that speak to social justice and resilience. Resist #2 (2021), by Mickalene Thomas, spoke to Traci Archable-Frederick as a representation of “then and now” from the 1960s Civil Rights Movement to the protests following the murders of Freddie Gray and George Floyd. Sara Ruark sees Karel Appel’s A World in Darkness (1962) as a reminder of how mankind falls apart during times of suffering, trauma, and horror. She also interprets Miniature Totem Pole (mid-20th century) by an unidentified Haida artist as a means of economic survival amidst the continued injustices faced by Indigenous people. Alex Dicken was drawn to the unusual color palette and absence of figures in Max Ernst’s Earthquake, Late Afternoon (1948), an ecological catastrophe that he noticed appears almost serene, but indicates a hidden crisis from a vantage point of a world without human observers.