Wednesday, July 11, 2012

Brushed with Light: American Landscape Watercolors

Brushed with Light: American Landscape Watercolors from the Collection showcased a selection of eighty works from the Brooklyn Museum’s extensive and highly regarded holdings of American landscape watercolors. The exhibition, on view September 14, 2007, through January 13, 2008 at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, explored the joint evolution of landscape and watercolor painting in the United States over the course of two centuries.

Included were paintings by America’s foremost practitioners of the medium, including William Trost Richards, Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, Childe Hassam, Maurice Prendergast, John Marin, and Edward Hopper. Ranging in date from 1777 to 1945, the works on view are arranged chronologically around the major movements in American landscape art: late-eighteenth-century topographical and Picturesque view painting; the Hudson River School and Pre-Raphaelitism; post-Civil War realism; American Impressionism; modernist abstraction; and American Scene painting. In addition to these sections, there wasan introduction to watercolor materials and techniques with illustrative examples.

In the colonial period, the American landscape was depicted by the trained draftsmen and watercolorists who recorded sites and terrain for the English and French governments. For such artists as Captain William Pierie (active late eighteenth century) landscape work was an extension of mapping.

While stationed in North America as an officer in the British royal artillery, Pierie produced topographical views such as Narrows at Lake George (1777). With its easy portability, watercolor was an ideal medium for this type of documentation.

By 1800, American landscape imagery gradually began to transition away from panoramic, topographical views to scenes based on British theories of the Picturesque.

This impulse to both document the landscape and to imbue it with Romantic sensibility was evident in George W. Beck’s (1748–1812) Stone Bridge over the Wissahickon (ca. 1800). Many of these works were reproduced and circulated in prints and books that, along with the Hudson River School of landscape painting, helped to foster widespread interest in American scenery.

A dramatic change in attitude toward the practice of watercolor came about in the United States beginning in the late 1850s with the Exhibition of English Art in 1857, which heightened the visibility of watercolor as fine art. It featured the work of the British Pre-Raphaelites, among them watercolor theorist John Ruskin. Ruskin’s espousal of absolute truth to nature inspired a group of American followers including William Trost Richards. Trained in the Hudson River School idiom and a founding member of the American Pre-Raphaelites, Richards began using watercolor in the 1870s to create naturalistic, highly detailed landscapes based on plein-air studies, as in Rhode Island Coast: Conanicut Island (ca. 1880) and

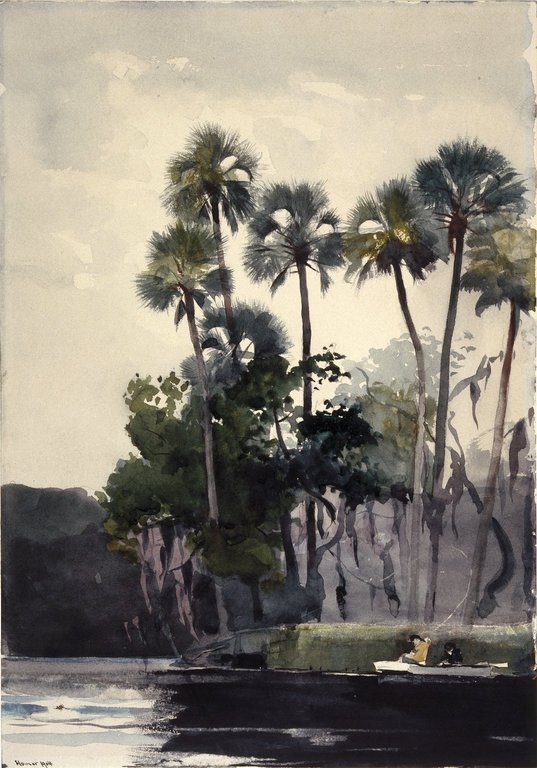

As more American artists began experimenting with watercolor, the so-called American Watercolor Movement was underway with professional societies, regular exhibitions, and supportive patrons. Winslow Homer (1836–1910), already established for his realistic illustrations and oil paintings, emerged as one of the leading figures in the movement.

In Fresh Air (1878), one of his early forays on the medium, Homer’s working method parallels that found in his oil paintings: he sketched this composition in pencil, then built up the volume of the figure with careful modeling of light and shade. By the end of his career, he was widely acknowledged as one of the greatest masters of the medium.

His late watercolors such as Homosassa River (1904) demonstrate both his intuitive approach and technical facility with the medium.

Led by innovators like Homer and the American Impressionists, American watercolorists broke new ground in the 1880s and began to explore the potential of the liquid medium. As never before, the play of natural light on landscape forms became the primary subject of their work. Inspired by the progressive realistic styles they saw in Europe, many artists adopted a freer approach to watercolor in order to convey their immediate impressions of nature with lively strokes of pure, bright color.

In The Gorge, Appledore (1912), Childe Hassam (1859–1935) captures the fleeting effects of light and color along the rugged coastline of the island off the coast of New Hampshire where he spent his summers.

During the same period, modernists began to experiment with abstract pictorial modes that referred to the formal structures or essences of their landscape subjects.

In paintings like John Marin’s (1870–1953) Pine Tree (1917), the bare white paper plays as vital a role as the dynamic components of the composition. Watercolor came to be associated with progressive art in the United States and it was considered a medium in which American artists equaled if not surpassed their European counterparts.

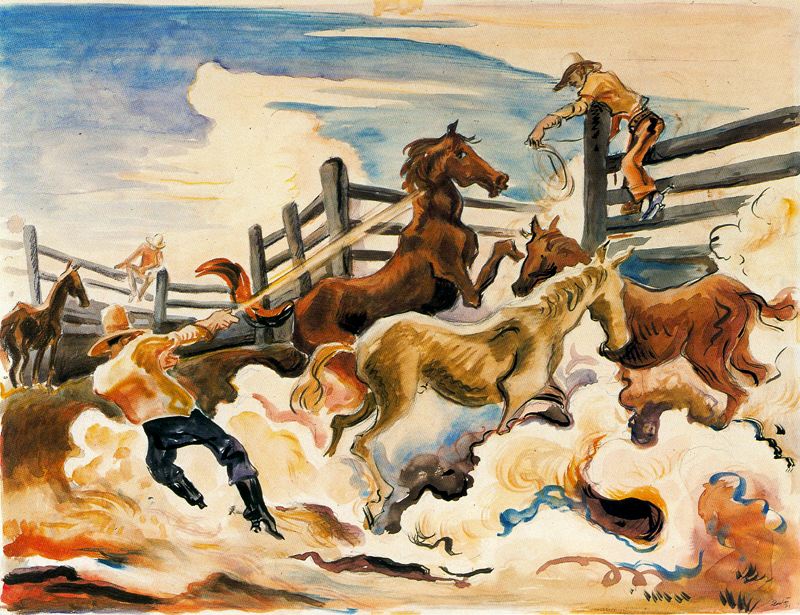

The American Scene Painting movement of the late 1920s–30s rejected most nineteenth-century ideas and devices in favor of unvarnished, typical American subjects, recording them with a new informality and sense of simplicity. Notable twentieth-century works in this vein include

Edward Hopper’s (1882–1967) House at Riverdale (1928)

and Thomas Hart Benton’s (1889–1975) Lassoing Horses (1931).

_-_overall.jpg)