Wednesday, July 11, 2012

Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera

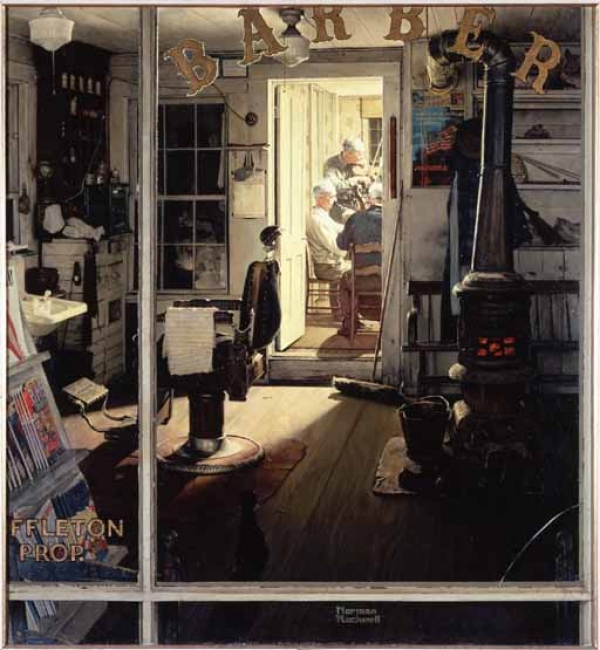

To create many of his iconic, quintessentially American paintings, most of which served as magazine covers, Norman Rockwell worked from carefully staged study photographs that are on view for the first time, alongside his paintings, drawings, and related tear sheets, in Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camera. The exhibition, on view at the Brooklyn Museum of Art from November 19, 2010, through April 10, 2011, was organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, following a two-year project that preserved and digitized almost 20,000 negatives.

Beginning in the late 1930s, Norman Rockwell (1894–1978) adopted photography as a tool to bring his illustration ideas to life in studio sessions. Working as a director, he carefully staged his photographs, selecting props, locations, and models and orchestrating every detail. He began by collecting authentic props and costumes, and what he did not have readily available he purchased, borrowed, or rented—from a dime-store hairbrush or coffee cup to a roomful of chairs and tables from a New York City Automat.

He created numerous photographs for each new subject, sometimes capturing complete compositions and, in other instances, combining separate pictures of individual elements. Over the forty years that he used photographs as his painting guide, he worked with many skilled photographers, particularly Gene Pelham, Bill Scovill, and Louis Lamone.

Early in his career Norman Rockwell used professional models, but he eventually found that this method inhibited his evolving naturalistic style. When he turned to photography, he turned to friends and neighbors instead of professional models to create his many detailed study photographs, which he found liberating. Working from black-and-white study photographs also allowed Rockwell more freedom in developing his final work.

“If a model has worn a red sweater, I have painted it red—I couldn’t possibly make it green.… But when working with photographs I seem able to recompose in many ways: as to form, tone, and color,” Rockwell once commented.

Included in the exhibition were more than one hundred framed digital prints alongside paintings, drawings, magazine tear sheets, photographic equipment, and archival letters, as well as an introductory film.

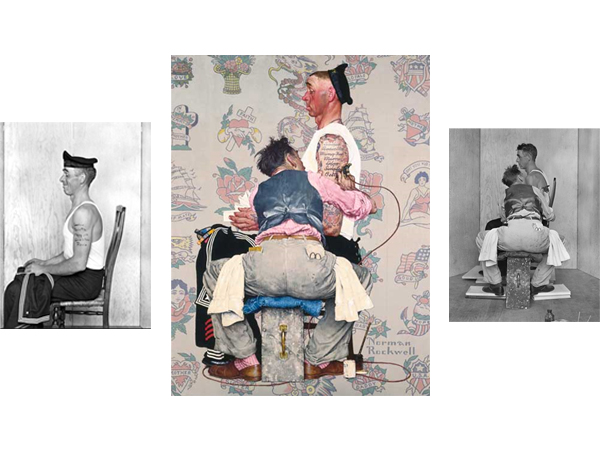

Among the paintings on view was the Brooklyn Museum’s painting The Tattoo Artist — one of many that Rockwell created during World War II — depicting a young sailor stoically having his arm tattooed, shown alongside working photographs by Gene Pelham,

and the watercolor Dugout, also from the Museum’s collection, portraying the Chicago Cubs baseball team being jeered by fans of the Boston Braves.

This work was displayed along with the September 4, 1948, Saturday Evening Post cover on which it appeared and study photographs by Gene Pelham.

Among the magazine covers included in the exhibition were several from The Saturday Evening Post, for which Rockwell worked for nearly fifty years before turning his attentions to more socially relevant subjects for Look magazine, with which he had a decade-long relationship.

Included was The Art Critic, showing an aspiring artist scrutinizing paintings in a gallery, which appeared in the April 16, 1955, issue.

The exhibition also included several series of photographs and the final paintings and magazine tear sheets, among them the July 13, 1946, Saturday Evening Post illustration Maternity Waiting Room, shown along with a series of images by an unidentified photographer that served as details of the final work, which portrays ten anxious soon-to-be fathers.

Norman Rockwell became one of the most famous illustrators of his generation through his naturalistic, narrative paintings done in a readily recognizable style, which appeared in national magazines that reached millions of readers. Born in 1894 on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, he left high school to study at the National Academy of Design and later the Art Students League of New York. By the age of eighteen he was already a published artist specializing in children’s illustration and had become a regular contributor to magazines such as Boys’ Life, the monthly magazine of the Boy Scouts of America, where he was soon named art director. In 1916 he painted his first cover for The Saturday Evening Post, beginning a forty-seven year relationship that resulted in 323 covers and was the centerpiece of his career.

Early in his career Rockwell had a studio in New Rochelle, New York. He later moved with his wife and three sons to Arlington, Vermont, where many of his family and neighbors served as models in working photographs for his illustrations, which began to focus on small-town American life. In 1943 a fire destroyed his Vermont studio, along with numerous paintings and many of the photographic studies. A decade later the family relocated to Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

In 1963 he severed his forty-seven- year association with The Saturday Evening Post and began to work for Look magazine, where, during his ten-year association, he produced work that reflected his personal concerns, including civil rights, America’s war on poverty, and space exploration.

Norman Rockwell: Behind the Camerawas organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum, where it was presented from November 7, 2009, through May 31, 2010. Conceived in collaboration with Ron Schick, guest curator for the Norman Rockwell Museum and author of

the accompanying publication, the exhibition revealed a rarely seen yet fundamental aspect of Rockwell’s creative process and unveils a significant new body of Rockwell imagery through the medium of photography. The Brooklyn Museum presentation was organized by Sharon Matt Atkins, Acting Head of Exhibitions and Managing Curator.