Tuesday, July 17, 2012

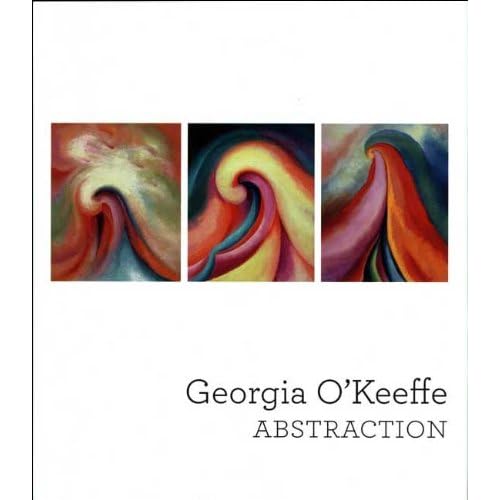

Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction

The artistic achievement of Georgia O’Keeffe was examined from a fresh perspective in Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction, a landmark exhibition debuting this fall at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

While O’Keeffe (1887–1986) has long been recognized as one of the central figures in 20th-century art, the radical abstract work she created throughout her long career has remained less well-known than her representational art.

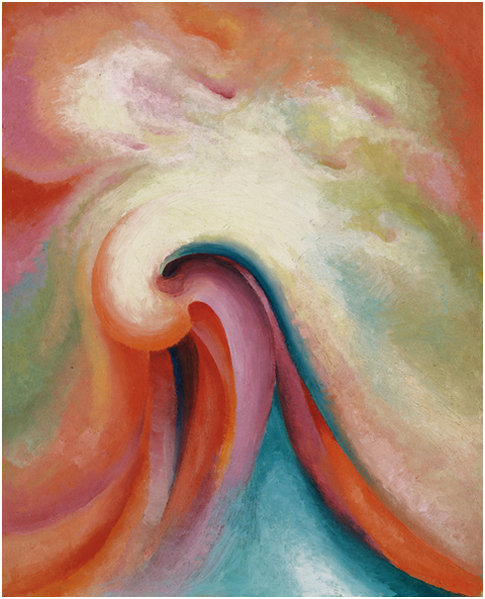

Georgia O’Keeffe, Blue Flower, 1918. Pastel on paper mounted on cardboard, 20 × 16 in. (50.8 × 40.6 cm). Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico; gift of The Burnett Foundation. © Private collection

By surveying her abstractions, Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction, repositioned O’Keeffe as one of America's first and most daring abstract artists. The exhibition was on view in the Whitney’s third-floor Peter Norton Family Galleries from September 17, 2009 through January 17, 2010.

Including more than 130 paintings, drawings, watercolors, and sculptures by O'Keeffe as well as selected examples of Alfred Stieglitz’s famous photographic portrait series of O’Keeffe, the exhibition had been many years in the making.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Untitled (Abstraction/Portrait of Paul Strand), 1917

The curatorial team, led by Whitney curator Barbara Haskell, included Barbara Buhler Lynes, the curator of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum and the Emily Fisher Landau Director of the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum Research Center; Bruce Robertson, professor of the history of art and architecture at the University of California, Santa Barbara; Elizabeth Hutton Turner, professor and vice provost for the arts at the University of Virginia and guest curator at The Phillips Collection; and Sasha Nicholas, Whitney curatorial assistant.

The exhibition was accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue with essays by the organizers, selections from the recently unsealed Stieglitz-O’Keeffe correspondence, and a contextual chronology of O’Keeffe’s life and work.

"Series I, No. 8," 1919, by Georgia O'Keeffe. Photo: Georgia O'Keeffe Museum/Artist Rights Society, New York

Following its Whitney debut, the show traveled to The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C., February 6-May 9, 2010, and to the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, May 28- September 12, 2010.

"Series I-No. 3," 1918. Photo: Milwaukee Art Museum

While it is true that O’Keeffe has entered the public imagination as a painter of sensual, feminine subjects, she is nevertheless viewed first and foremost as a painter of places and things. When one thinks of her work it is usually of her magnified images of open flowers and her iconic depictions of animal bones, her Lake George landscapes, her images of stark New Mexican cliffs, and her still lifes of fruit, leaves, shells, rocks, and bones. Even O’Keeffe’s canvasses of architecture, from the skyscrapers of Manhattan to the adobe structures of Abiquiu, come to mind more readily than the numerous works—made throughout her career—that she termed abstract.

From the Lake, 1924

This exhibition was the first to examine O'Keeffe's achievement as an abstract artist. In 1915, O'Keeffe leaped into the forefront of American modernism with a group of abstract charcoal drawings that were among the most radical creations produced in the United States at that time. A year later, she added color to her repertoire; by 1918, she was expressing the union of abstract form and color in paint.

Georgia O’Keeffe Flower Abstraction, 1924 Oil on canvas, 48 x 30 in. (121.9 x 76.2 cm) Whitney Museum of American Art, New York 50th Anniversary Gift of Sandra Payson 85.47 Copyright Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

First exhibited in 1923, O’Keeffe’s psychologically charged, brilliantly colored abstract oils garnered immediate critical and public acclaim. For the next decade, abstraction would dominate her attention. Even after 1930, when O’Keeffe’s focus turned increasingly to representational subjects, she never abandoned abstraction, which remained the guiding principle of her art. She returned to abstraction in the mid-1940s with a new, planar vocabulary that provided a precedent for a younger generation of abstractionists.

Early Abstraction, 1915 Abstraction and representation for O’Keeffe were neither binary nor oppositional. She moved freely from one to the other, cognizant that all art is rooted in an underlying abstract formal invention. For O’Keeffe, abstraction offered a way to communicate ineffable thoughts and sensations. As she said in 1976, “The abstraction is often the most definite form for the intangible thing in myself that I can only clarify in paint.” Through her personal language of abstraction, she sought to give visual form (as she confided in a 1916 letter to Alfred Stieglitz) to “things I feel and want to say - [but] havent [sic] words for.” Abstraction allowed her to express intangible experience—be it a quality of light, color, sound, or response to a person or place. As O’Keeffe defined it in 1923, her goal as a painter was to “make the unknown—known. By unknown I mean the thing that means so much to the person that he wants to put it down—clarify something he feels but does not clearly understand.”

Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, 1918

This exhibition and catalogue chronicled the trajectory of O'Keeffe's career as an abstract artist and examine the forces impacting the changes in her subject matter and style. From the beginning of her career, she was, as critic Henry McBride remarked, “a newspaper personality.” Interpretations of her art were shaped almost exclusively by Alfred Stieglitz, artist, charismatic impresario, dealer, editor, and O’Keeffe’s eventual husband, who presented her work from 1916 to 1946 at the groundbreaking galleries “291”, the Anderson Galleries, the Intimate Gallery, and An American Place. Stieglitz’s public and private statements about O’Keeffe’s early abstractions and the photographs he took of her, partially clothed or nude, led critics to interpret her work—to her great dismay—as Freudian-tinged, psychological expressions of her sexuality.

Abstraction Blue

Cognizant of the public’s lack of sympathy for abstraction and seeking to direct the critics away from sexualized readings of her work, O’Keeffe self-consciously began to introduce more recognizable images into her repertoire in the mid-1920s. As she wrote to the writer Sherwood Anderson in 1924, “I suppose the reason I got down to an effort to be objective is that I didn’t like the interpretations of my other things [abstractions].” O’Keeffe’s increasing shift to representational subjects, coupled with Stieglitz’s penchant for favoring the exhibition of new, previously unseen work, meant that O’Keeffe’s abstractions rarely figured in the exhibitions Stieglitz mounted of her work after 1930, with the result that her first forays into abstraction virtually disappeared from public view.

Catalogue

In addition to rethinking O'Keeffe's place in American modernism, the book that accompanied this exhibition reappraises the origin and singular character of her abstract vocabulary and the stylistic shifts which her art underwent over the span of her long career. It adds significant new insight into her art and life, publishing for the first time excerpts of recently unsealed letters written by O’Keeffe to photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, whom she married in 1924. These letters, along with a contextual chronology and other primary documents referenced by the authors, offer an intimate glimpse into her creative method and intentions as an artist. Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction, was organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC; and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, NM.

Nice review, more images