John Singer Sargent Watercolors on View at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from October 13, 2013, to January 20, 2014.

First Expansive Sargent Watercolor Exhibition in Twenty Years Combines Holdings from Brooklyn Museum and Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Previously on view at the Brooklyn Museum April 5 through July 28, 2013

The Brooklyn Museum, together with the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, has organized the landmark exhibition John Singer Sargent Watercolors, which unites for the first time the holdings of Sargent watercolors acquired by each of the two institutions in the early twentieth century. The ninety-three watercolors in the exhibition—including thirty-eight from Brooklyn’s collection, most of which have not been on view for decades—provide a once-in-a-generation opportunity to view a broad range of Sargent’s finest production in the medium.

Brooklyn’s Sargent watercolors were purchased en masse from the artist’s 1909 debut exhibition in New York. Their subjects include Venice scenes, Mediterranean sailing vessels, intimate portraits, and the Bedouin subjects, executed during a 1905–6 trip through the Ottoman Levant, that Sargent considered among the most outstanding works of the group. Among the Brooklyn watercolors are

Santa Maria della Salute (1904),

a carefully wrought painting that explores in detail the features of one of Venice’s greatest works of architecture;

The Bridge of Sighs (circa 1903–4),

a vigorously painted work that captures the action of gondoliers at work;

Bedouins (circa (1905–6),

a watercolor of expressive force and coloristic vibrancy completed during Sargent’s travels in Syria;

A Tramp (circa 1904–6),

a portrait of a world-weary man notable for its intimacy and directness;

Gourds (1908),

distinctive for its dense brushwork and brilliant palette;

and In a Medici Villa (1906),

which reveals the artist’s love of formal Italian gardens and his preference for unexpectedly framed compositions.

The watercolors purchased by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1912, were painted by Sargent with his Boston audience in mind and are more highly finished than the Brooklyn works. They feature subjects from his more recent travels to the Italian Alps, the villa gardens near Lucca, and the marble quarries of Carrara, as well as portraits.

Included are

Corfu: Lights and Shadows (1909),

a work that explores the colors and tones of sunlight and shadows cast on brilliant white surfaces;

Simplon Pass: Reading (circa 1911),

which highlights the artist’s affinity for luxuriant compositions of casually interlinked figures;

The Cashmere Shawl (circa 1911),

a work that approximates the verve and virtuosity of Sargent’s grand portraits in oil;

Carrara Lizzatori I (1911),

a dynamic impression of the quarry;

and Villa di Marlia, Lucca: A Fountain (1910),

which captures the vibrant interplay of light and shadow around which Baroque gardens were designed.

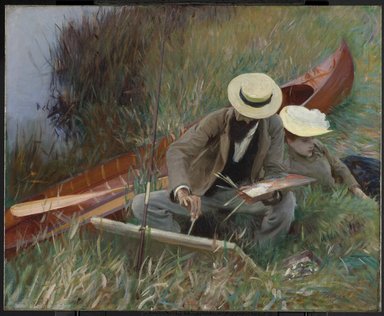

The exhibition will also present nine oil paintings, including Brooklyn’s

An Out-of-Doors Study, or Paul Helleu and His Wife (1889),

and Boston’s The Master and His Pupils (1914).

The culmination of a yearlong collaborative study by a team of curators and conservators from both museums, John Singer Sargent Watercolors explores the extension of the artist’s primary aesthetic concerns throughout his watercolor practice, which has traditionally been viewed as a tangential facet of his art making. New discoveries based on scientific study of Sargent’s pigments, papers, drawing techniques, paper preparation, and application of paint will be featured in a special section of the exhibition that deconstructs the artist’s techniques. In addition, select works throughout the exhibition will be paired with videos that show a contemporary watercolor artist demonstrating some of Sargent’s working methods.

The exhibition was on view at the Brooklyn Museum from April 5 to July 28, 2013, and will be on vieat the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, from October 13, 2013, to January 20, 2014. It will then travel to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

John Singer Sargent Watercolors is organized by the Brooklyn Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The exhibition is co-curated by Teresa A. Carbone, Andrew W. Mellon Curator of American Art, Brooklyn Museum; and Erica E. Hirshler, Croll Senior Curator of American Paintings, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Other members of the project team include Antoinette Owen, Senior Conservator, Brooklyn Museum; and Annette Manick, Head of Paper Conservation, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

From the Huffington Post with lots more images:

The exhibition, titled, "John Singer Sargent Watercolors," stretches the artist's legacy from conventional portraitist to a experimental painter on the brink of modernism.

John Singer Sargent (American, 1856–1925). Mountain Fire, circa 1906–7. Opaque and translucent watercolor, 14 1/16 x 20 in. (35.5 x 50.8 cm). Brooklyn Museum.

For the massive show, The Brooklyn Museum combined the 38 works in its own collection with those from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The combined selection follows Sargent on a soul-searching journey from Venice to Syria to the Italian Alps and beyond, spanning the key decade from 1902 until 1912.

Sargent's medium shapeshifts with the territory he depicts; sometimes the diluted pigment fades into translucent vapor. In other works Sargent squeezes color straight from the tube, producing bulky paint that camouflages as acrylic or even pastel. In his "Bedouin" series Sargent pushes watercolor to its limit, its thickness so overpowering the paint begins to crack, giving his subjects the impression of being scorched in the sun.

At the exhibition preview Arnold L. Lehman, director of the Brooklyn Museum, lingered in front of a particular painting entitled

"Corfu: A Rainy Day,"

in which a woman rests on the couch, her shoes strewn beside her on the floor. Although the subject's dress was rumpled in delightful disarray around her, Lehman's attention lingered on the shoes. "The informality of those shoes," he said. "Nobody else would think to do that. The informality, it's a symbol of contemporary life."

Sargent floats in the peculiar space between a formal society portrait and an avant-garde experimental work, making him nearly impossible do define or pin down in the evolution of modern art. With brevity, curiosity and informality Sargent remakes the world in watercolors, teasing with the existing rules of representation though not outwardly rebelling against them. The exhibition suggests that sometimes the most interesting aesthetic move is not the most radical one. Sargent chose to dwell somewhere between old-fashioned and modern, not creating to rupture artistic tradition but simply for the pleasure of travel and paint.

From a great, not to be missed, review, with lots more images:

Watercolors are particularly apt to fade in light. That is the chief reason that the public at large has never seen these items. After the show these paintings will likely go back to storage. And despite the fact that many of works are available online and all can be seen in the exhibition’s excellent catalogue by Erica E. Hirshler and Teresa A. Carbone (with contributions by others), neither viewing can substitute for a personal inspection of the originals, which show the nature of the washes, the texture of the paper and where it was wetted, the layers of the paint, Sargent’s uses of opaque pigments and wax resists, his intentional scrapings, and most importantly his bold brushstrokes. The originals of watercolors differ much more from their reproduction in print, slides or other backlit renderings than do similar reproductions of oils because many of the pigments used in watercolors are translucent, a quality that cannot be captured by the other forms of publication. So this exhibition is literally a once in a lifetime opportunity to experience the bulk of a major phase of an artist’s career that is more written about than seen...

This show represents the merging of two complete collections of watercolors selected by Sargent himself a century ago. One collection (owned by the Brooklyn Museum) came from Sargent’s first major American watercolor exhibition, which took place at New York’s Knoedler Gallery in 1909. Although Sargent had several times mounted highly successful watercolor shows in London, he was reluctant to undergo to the trouble and expense of boxing, shipping, insuring and clearing the works through customs. There would be no prospect of immediate financial rewards because Sargent, as a matter of principle, never sold his watercolors... A quarter of a century later, Sargent eventually came around to the idea of a New York watercolor show.

Evidently one of the first to see the 1909 show at Knoedler Gallery was Brooklyn Museum president Aaron Augustus Healy. Healy had long been an admirer of Sargent. Two years before the Knoedler show he sat for a formal portrait by Sargent. Healy had also recently purchased Sargent’s Dolce Far Niente (left). Sensing an opportunity to strike a handsome bargain, Healy quickly arranged an offer. The museum would pay $20,000 for the entire set of paintings. Sargent’s main objection to selling, it seems, was the belief that one watercolor was too ephemeral to stand alone. He regarded the collection as the work of art. Faced with the offer, Sargent agreed, and all 83 paintings, went to Brooklyn. (Only about 50 of these paintings are in the Brooklyn exhibition, the museum having sold some of the items since the purchase...)

The Boston Museum of Fine Arts was caught flat-footed by the sale, which took place even before the exhibition made its was to Boston. Although Sargent was born in Florence (in 1856) and did not visit the United States until he was twenty (and spent little time thereafter), he always regarded himself as an American. (He declined George VII’s offer of a knighthood believing he would have to give up his U.S. citizenship to accept.) He considered Boston “home,” because his father’s family was one of the oldest New England families, dating back to colonial times. (Sargent’s grandfather, however, moved, when his shipping business failed, from Gloucester to Philadelphia, where Sargent’s father maintained a successful eye surgery practice before going abroad with his wife...)

All of the items selected for the second American exhibition he signed, anticipating a sale. In the Museum of Fine Arts acquired the 50 watercolors even before they were exhibited in 1912. Those watercolors are also part of the present Brooklyn Museum exhibition.

From the NY Times (images added):

Was Sargent a modern artist?

He was modern in the sense that he revealed the processes of painting, unlike conservative academicians who preferred to hide their tricks behind veils of illusion. Because of its transparency watercolor has a certain intelligibility; you can see the artist thinking, deciding and constructing the work. With

“White Ships” (around 1908)

you can visually dissect Sargent’s dazzling picture of sailing vessels drenched by sunlight in a Majorca harbor. Every gesture represents something — masts, rigging, sails, reflections in the water — yet each mark and stain retains its distinctly material identity.

There are many instances of Sargent doing this to arresting affect, like

“Brook Among Rocks” (1906-8),

which shows a limpid mountain stream, and

“La Biancheria” (1910),

which pictures white laundry hanging on clotheslines in a verdant yard bathed in bright sunlight.

The exhibition’s nine oil paintings, including another rocky pool on canvas, are dark and leaden by comparison.

Sargent was modern in another, broader way if you consider the impulse to find freedom from constraint as a fundamental drive of 20th-century art. But the freedom that Sargent sought, beyond that of aesthetic expression, was not like that of the avant-garde. He wanted to escape the portrait studio, a golden cage of his own making. But he showed no urge to liberate himself from the social mores of his upper-crust class. On expeditions to the Alps he stayed in a hotel with an entourage including his two sisters and other family members and friends. Lounging in the Alpine grass wielding fancy parasols while voluminously bundled in swaths of white fabric, these women look as if they are dolled up for a garden party in several paintings.

“Spanish Soldiers” (around 1903) offers possible erotic intrigue. A slender young man in red trousers and a white military blouse leans against a pillar in a sinuous posture with folded arms, gazing out at the viewer with a sweet, enigmatic expression. But this is a rare moment: Sargent’s watercolors, though diaristic, are usually psychologically opaque.