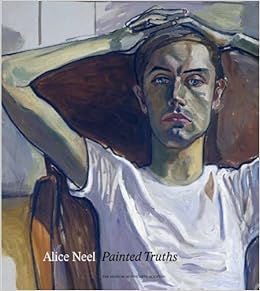

Alice Neel: Painted Truths opened at the Museum of Fine Arts,

Houston on 21 March, 2010 and closed on 13 June. This survey of 68 paintings was arranged thematically and includes portraits and cityscapes from all

phases of Neel's career. The exhibition traced Neel's style and examines

the themes of Allegory, The Essential Portrait, the Psychological

Portrait, Portraits from Memory, Cityscapes, Parent and Child, the

Detached Gaze and Old Age.

This was the first major exhibition and publication on Alice Neel since the 2000 retrospective. After its Houston showing it traveled to the Whitechapel Gallery, London and the Moderna Museet, Malmö.

Widely regarded as one of the most important American painters of the 20th century, Alice Neel is internationally recognized for her contributions to Abstract Expressionism, especially her perceptive portraiture. Neel (1900–1984) was a portrait painter at a time when this was traditionally the role of a male artist. After ascending to prominence in the 1960s as the feminist movement gained momentum, she has remained an iconic figure in the history of American painting.

A self-proclaimed “collector of souls,” Neel often painted friends and family, as well as the celebrated artists and writers of her day, such as Andy Warhol, Frank O’Hara, and Meyer Shapiro, delving into personalities and idiosyncrasies with a rare frankness. Alice Neel: Painted Truths brings together paintings that demonstrate Neel’s range and ability, along with insightful commentary from four leading art historians.

Although the book focuses on her portraits, it also covers the artist’s early social realist paintings and cityscapes, tracing the evolution of Neel’s style and examining themes that she revisited throughout her career. It contains essays by co-curators Jeremy Lewison and Barry Walker as well as Tamar Garb and Robert Storr. There are also artist's appreciations by Frank Auerbach, Marlene Dumas and Chris Ofili, thematic introductions and catalogue entries.

From the arts desk.com: (some images added)

Outstanding review

This was the first major exhibition and publication on Alice Neel since the 2000 retrospective. After its Houston showing it traveled to the Whitechapel Gallery, London and the Moderna Museet, Malmö.

Widely regarded as one of the most important American painters of the 20th century, Alice Neel is internationally recognized for her contributions to Abstract Expressionism, especially her perceptive portraiture. Neel (1900–1984) was a portrait painter at a time when this was traditionally the role of a male artist. After ascending to prominence in the 1960s as the feminist movement gained momentum, she has remained an iconic figure in the history of American painting.

A self-proclaimed “collector of souls,” Neel often painted friends and family, as well as the celebrated artists and writers of her day, such as Andy Warhol, Frank O’Hara, and Meyer Shapiro, delving into personalities and idiosyncrasies with a rare frankness. Alice Neel: Painted Truths brings together paintings that demonstrate Neel’s range and ability, along with insightful commentary from four leading art historians.

Although the book focuses on her portraits, it also covers the artist’s early social realist paintings and cityscapes, tracing the evolution of Neel’s style and examining themes that she revisited throughout her career. It contains essays by co-curators Jeremy Lewison and Barry Walker as well as Tamar Garb and Robert Storr. There are also artist's appreciations by Frank Auerbach, Marlene Dumas and Chris Ofili, thematic introductions and catalogue entries.

From the arts desk.com: (some images added)

A self-portrait by Alice Neel, aged 80

In her only self-portrait (main picture), painted in 1980, four years before her death, she looks formidable. Aged 80, naked and with a spindly brush in one hand and a rag in the other, she belies, with her fearsome look, her physical vulnerability: the stubbornly down-turned mouth, an eyebrow raised in a disdainful and defiant arch (disdainful, perhaps, of her own reflection or of us); and her hair like a steel helmet, not the mass of grey, formless, candyfloss we see in the film.

Degenerate Madonna, 1930, shows the influence of German Expressionism, though its mannered stylisation hides nothing of the pitiless rawness of self-hatred.

InSymbols (Doll and Apple), c 1933another doll-child sits slumped and twisted-limbed, surrounded by Christian imagery. Its style is that of the Latin American devotional painting. More perplexingly, an apple hides its genitals, another apple is held in one hand and a huge red glove is worn in the other. It was painted soon after Neel was discharged from a hospital following her mental breakdown.

You can see Neel’s style shift according to who she was painting and what he or she represented. She even flirts with socialist realism. Pat Whalen, 1935, shows the fervently committed Communist staring into the middle-distance of a promised future, his heavy, oversized fists clenched over a copy of the Daily Worker, the organ of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA).

Elsewhere, heavily worn Neue Sachlichkeit caricature informs her painting of Audrey McMahon, 1940(pictured left). McMahon was the director of the New York division of the New Deal’s Federal Art Project and was an unpopular figure among many artists, including Neel. McMahon stares out of the canvas with a face as brown and as hard and as shrunken as a shrivelled nut.

It is not until the Sixties that Neel’s dense, dark palette lifts, and she becomes thoroughly and recognisably "Alice Neel". She begins to paint fellow artists, curators and writers but also returns again and again to the theme of Mother and Child. These are unlike the earlier Degenerate Madonna, yet many unflinchingly depict the anxiety and often sheer shock of new motherhood. Among the most arresting – and I think one of the strongest paintings in the exhibition – is Mother and Child (Nancy and Olivia), 1967 (pictured right). Neel’s daughter-in-law sits hugging her baby as if it were a life buoy and her saucer-wide eyes betray her utter bewilderment. A later portrait of Nancy with five-month-old twins, painted in 1971, shows someone altogether more practised at motherhood, transformed by self-assurance.

Neel was always interested in getting under the skin of her sitters and one certainly feels her portrait of Andy Warhol (pictured left) – an artist whose interest lay only in surface – achieves this. At the very least it succeeds in portraying the humanity behind the almost impenetrable coolness of his image. Painted in 1970, two years after his near fatal shooting by Factory hanger-on/stalker Valerie Solanas, Warhol sits on a cartoon outline of a sofa. He is stripped to the waist, his eyes closed. He might be inwardly flinching at our unwavering gaze, but his face conveys dignified self-possession.

We survey the scars of his gunshot wounds, his pendulous man-breasts, the bulging surgical corset. His frame is fragile, almost feminine. And the paint is so thinly applied that he looks ethereal, his feet barely anchored to the ground. He might float off at any moment. We, however, are rooted to the spot.

Outstanding review