MFA, Boston (July 16–December 28, 2014);

Brandywine River Museum of Art (January 16–April 5, 2015);

San Antonio Museum of Art (April 26–July 5, 2015); and

Crystal Bridges Museum of Art (July 23–October 4, 2015).

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA) has organized the first major retrospective of American artist Jamie Wyeth (born 1946). Featuring 109 works, Jamie Wyeth examines six decades of the artist’s career and charts the evolution of his creative process from his earliest childhood drawings through recurring themes inspired by the people, places and objects that populate his world. The third generationin a family of artists––including his grandfather, Newell Convers “N.C.” Wyeth (1882–1945); his father, Andrew Wyeth (1917–2009); and his aunt, Carolyn Wyeth (1909–1994)––Jamie Wyeth has blazed his own unique path.

The exhibition displays paintings, works on paper, illustrations and objects in a range of “combined mediums”––Wyeth’s preferred term for the distinctive technique he brings to many of his compositions. Organized by the MFA and accompanied by an illustrated catalogue, the exhibition is on view in the Lois and Michael Torf Gallery through December 28, 2014, before traveling to three additional venues: Brandywine River Museum of Art, Pennsylvania (January 16–April 5, 2015); San Antonio Museum of Art (April 26–July 5, 2015); and Crystal Bridges Museum of Art, Arkansas (July 23–October 4, 2015).

The exhibition displays paintings, works on paper, illustrations and objects in a range of “combined mediums”––Wyeth’s preferred term for the distinctive technique he brings to many of his compositions. Organized by the MFA and accompanied by an illustrated catalogue, the exhibition is on view in the Lois and Michael Torf Gallery through December 28, 2014, before traveling to three additional venues: Brandywine River Museum of Art, Pennsylvania (January 16–April 5, 2015); San Antonio Museum of Art (April 26–July 5, 2015); and Crystal Bridges Museum of Art, Arkansas (July 23–October 4, 2015).

Wyeth began his artistic career at a young age, and while he left formal artistic education at age 11, would go on to study anatomy in a New York City morgue and work in Andy Warhol’s studio, The Factory.The exhibition offers a sense of the artist’s development over 60 years, from portraits made during his time in New York to landscapes of the worlds he inhabits in the Brandywine River Valley (between Pennsylvania and Delaware) and Mid coast Maine––especially Tenants Harbor and Monhegan Island.

Organized into several themes, Jamie Wyeth includes portraits of subjects such as John F. Kennedy; Jamie’s wife, Phyllis; Rudolf Nureyev; and Arnold Schwarzenegger shown alongside a selection of preparatory drawings and studies that offer a window into the artist’s immersive approach to portraiture. Still lifes of pumpkins (a fascination from his youth), images inspired by his participation in NASA’s “Eyewitness to Space” program, and his scenes of The Seven Deadly Sins as enacted by seagulls, all display Wyeth’s range and virtuosity.

Organized into several themes, Jamie Wyeth includes portraits of subjects such as John F. Kennedy; Jamie’s wife, Phyllis; Rudolf Nureyev; and Arnold Schwarzenegger shown alongside a selection of preparatory drawings and studies that offer a window into the artist’s immersive approach to portraiture. Still lifes of pumpkins (a fascination from his youth), images inspired by his participation in NASA’s “Eyewitness to Space” program, and his scenes of The Seven Deadly Sins as enacted by seagulls, all display Wyeth’s range and virtuosity.

Wyeth’s family context is explored with works including his childhood drawings and earliest portraits––created in his father’s and grandfather’s studios, where he initially worked under the tutelage of his aunt Carolyn after he left his formal schooling at age 11.

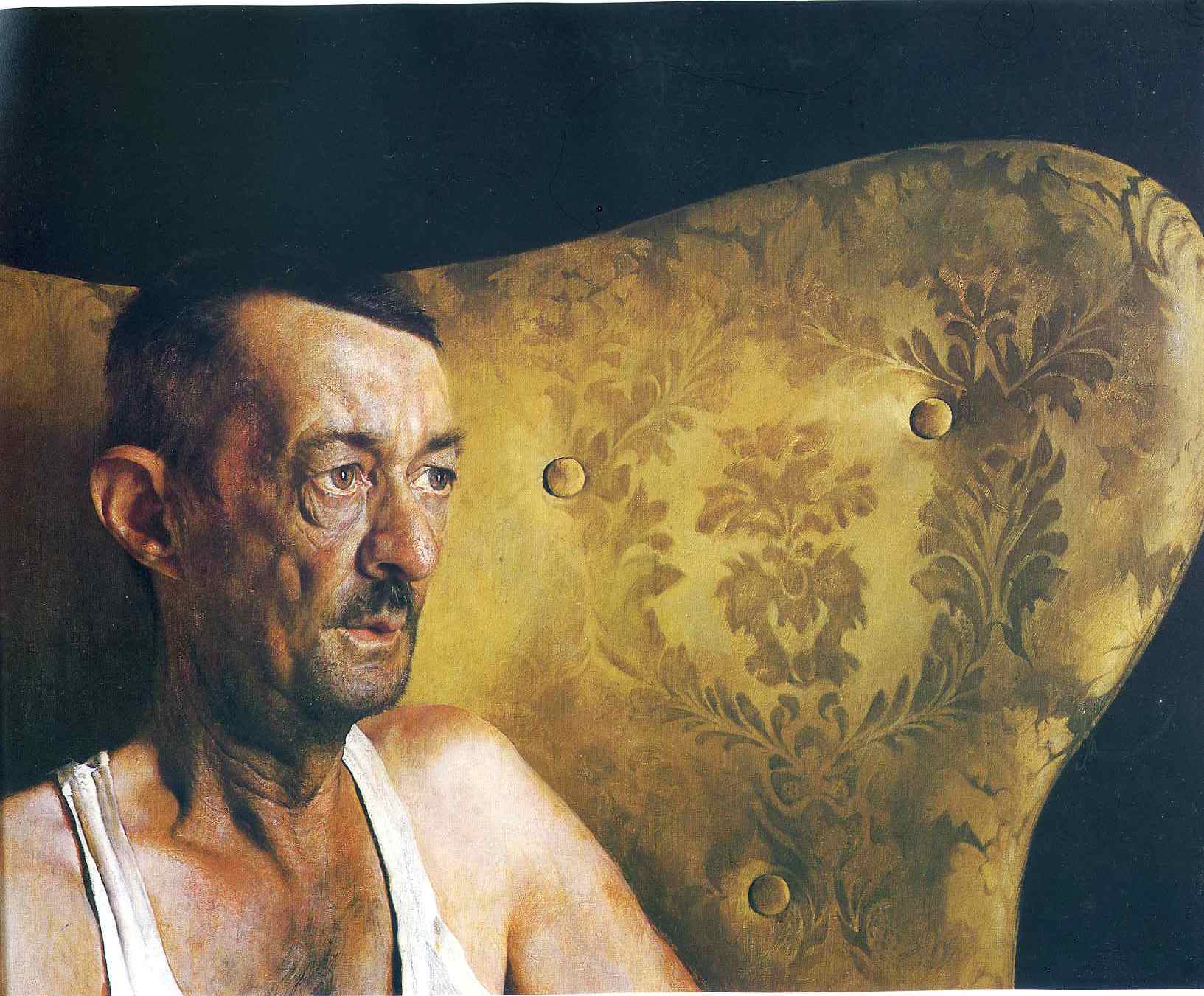

Wyeth’sPortrait of Shorty (1963), painted when he was 17, reflects the culmination of his early years as an apprentice within his own family circle. The portrait vividly demonstrates Wyeth’s preference for jarring contrasts—seen in the juxtaposition of Shorty’s grizzled face against the elaborately patterned silk brocade upholstery. The composition also reveals Wyeth’s fascination for the realists that he was especially drawn to––Jan van Eyck, John Singleton Copley and Thomas Eakins. Portrait of Shorty may have served to announce to his parents and his early teacher, Aunt Carolyn, that he had mastered the full repertoire of artistic tools and was now capable of going head-to-head with these famed artists, as well as the adult members of his own family.

Wyeth’sPortrait of Shorty (1963), painted when he was 17, reflects the culmination of his early years as an apprentice within his own family circle. The portrait vividly demonstrates Wyeth’s preference for jarring contrasts—seen in the juxtaposition of Shorty’s grizzled face against the elaborately patterned silk brocade upholstery. The composition also reveals Wyeth’s fascination for the realists that he was especially drawn to––Jan van Eyck, John Singleton Copley and Thomas Eakins. Portrait of Shorty may have served to announce to his parents and his early teacher, Aunt Carolyn, that he had mastered the full repertoire of artistic tools and was now capable of going head-to-head with these famed artists, as well as the adult members of his own family.

At the age of 17, Wyeth also received his first formal commission––to paint pioneering pediatric cardiologist Helen Taussig. Denied admission to Harvard Medical School because she was a woman, Taussig received her M.D. from Johns Hopkins, went on to become the second female member of the tenured faculty and is still considered one of the institution’s most distinguished doctors.

Working with a head-on format that is often used to represent omnipotent or regal figures, Wyeth captured Taussig’s intense intellectual focus by featuring her clear blue eyes as the windows of the soul. The neckline on her dress slips off her shoulder, suggesting that her appearance was of little interest to her––in striking contrast to her gaze. When the portrait, Helen Taussig (1963), was formally unveiled at Johns Hopkins before Taussig’s colleagues and friends, it elicited tears and gasps of horror. Although there was no long-standing tradition of portraiture for women doctors at the time, the painting’s confrontational pose was not what viewers expected to see. Shown in the artist’s first professional exhibition held in New York City in 1966, Helen Taussighas rarely been seen by the public and is on display in a museum for the first time since it was painted, providing an opportunity to see the work 50 years after it first shocked viewers.

Wyeth’s formative years during the 1960s and 1970s produced paintings such as his

Portrait of John F. Kennedy (1967),

which was initially discussed as a commission by the Kennedy family after the President’s death. Wyeth agreed to paint the posthumous portrait only if he could be given full access to the former President’s brothers, and, if he could ultimately retain the work. To create the likeness, the artist embarked on an intensely immersive process, producing scores of drawings––several of which are included in the exhibition. In the final portrait, the President leans on his fist as if in deep thought, with one eye looking toward the viewer and the other wandering off into the distance––a glance that Wyeth observed while campaigning with Edward Kennedy. The remarkably lifelike image was embraced by Jacqueline Kennedy, but rejected by Robert Kennedy, who felt Kennedy’s disconcerted look was a painful reminder of his demeanor during the Bay of Pigs invasion.

Portrait of John F. Kennedy (1967),

which was initially discussed as a commission by the Kennedy family after the President’s death. Wyeth agreed to paint the posthumous portrait only if he could be given full access to the former President’s brothers, and, if he could ultimately retain the work. To create the likeness, the artist embarked on an intensely immersive process, producing scores of drawings––several of which are included in the exhibition. In the final portrait, the President leans on his fist as if in deep thought, with one eye looking toward the viewer and the other wandering off into the distance––a glance that Wyeth observed while campaigning with Edward Kennedy. The remarkably lifelike image was embraced by Jacqueline Kennedy, but rejected by Robert Kennedy, who felt Kennedy’s disconcerted look was a painful reminder of his demeanor during the Bay of Pigs invasion.

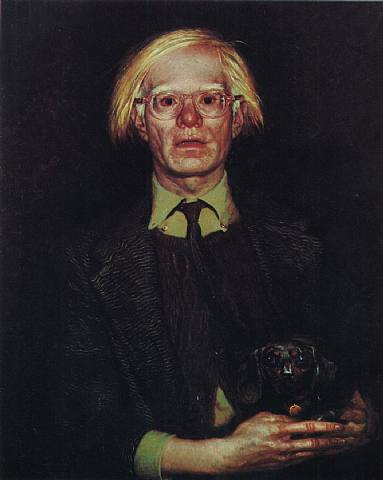

While working in New York City, Wyeth exchanged portraits with Andy Warhol at his famed Factory in 1976. Warhol was a master at playing the role of detached impresario of the Factory, and was known to draw in young talent, like Wyeth, to supply new ideas and direction. For Wyeth, a public portrait exchange with Warhol had the potential to highlight his immersive method of portrait painting at a time when critics favored more conceptual approaches. Wyeth brought all his tools and skills to bear on Warhol’s every pore, blemish and strand of his carefully styled wig.

Portrait of Andy Warhol (1976) boldly countered the popular perception of the image-conscious Warhol––one of the most famous and celebrity-conscious artists.

Portrait of Andy Warhol (1976) boldly countered the popular perception of the image-conscious Warhol––one of the most famous and celebrity-conscious artists.

In contrast to New York City and the Factory, the Brandywine River Valley inspired Wyeth to paint the barns, objects and landscapes of the picturesque agrarian region where he was born. Works focusing on the area surrounding his childhood home in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania and, later, on the Wyeths’ farm in Wilmington, Delaware, include early landscapes produced when the artist was 13 years old, and a series of carriage scenes depicting his wife––who suffered an automobile accident at the age of 21 that left her paralyzed. Portraits of local children, farm animals, birds, hay, barns––such as the flag-draped Patriot’s Barn (2001) ––and the artist’s beloved family pets, including his Yellow Labrador Retriever,

Kleberg (1984),

also form an important part of the exhibition.

also form an important part of the exhibition.

His paintings of Maine are primarily inspired by Southern Island and Monhegan Island, where both his father and grandfather have lived and worked since the early 20th century. Wyeth evokes a sense of the sublime found in the terrifying rawness of nature, which can be seen in the series, The Seven Deadly Sins (2005), and Inferno, Monhegan(2006)––a work that appears in a short documentary film of the artist creating the composition.

The untamed, feral qualities of Maine come across vividly in paintings of Orca Bates, a boy whose parents lived on Manana, the island just off Monhegan. In

Orca Bates (1990),

Wyeth posed the boy seated nude, capturing his subject with an unexpected, searing bite. Orca sits at attention on the hard edge of a massive seaman’s chest––which is large enough to have served for a burial at sea. His hair appears wet, and the whale jaw behind him may be a reminder of the biblical story of Jonah being swallowed by a whale.

The untamed, feral qualities of Maine come across vividly in paintings of Orca Bates, a boy whose parents lived on Manana, the island just off Monhegan. In

Orca Bates (1990),

Wyeth posed the boy seated nude, capturing his subject with an unexpected, searing bite. Orca sits at attention on the hard edge of a massive seaman’s chest––which is large enough to have served for a burial at sea. His hair appears wet, and the whale jaw behind him may be a reminder of the biblical story of Jonah being swallowed by a whale.

Wyeth’s most recent works in the exhibition include

Berg (2012),

which was based on his experience of being thrown out of a launch headlong into the frigid waters of Tenants Harbor, as well as a series of three paintings made since 2009, depicting a recurring dream of his artistic mentors—Winslow Homer, Andy Warhol, N.C. and Andrew Wyeth—posed in various configurations on the dramatic cliffs of the Monhegan Headlands.

Other recent works include Sleepwalker (2013) and two mixed media assemblages that the artist calls “tableaux vivant”: The Factory Dining Room and La Côte Basque (2013), both recalling Wyeth’s New York City experiences. Never shown before, these two miniature compositions––painted and sculpted at one-sixth to life scale––connect Wyeth’s vision to a long tradition of surrealist and realist assemblage, and introduce yet another dimension of the imaginative worlds that inspire his creative process and, ultimately, his compositions.

Berg (2012),

which was based on his experience of being thrown out of a launch headlong into the frigid waters of Tenants Harbor, as well as a series of three paintings made since 2009, depicting a recurring dream of his artistic mentors—Winslow Homer, Andy Warhol, N.C. and Andrew Wyeth—posed in various configurations on the dramatic cliffs of the Monhegan Headlands.

Other recent works include Sleepwalker (2013) and two mixed media assemblages that the artist calls “tableaux vivant”: The Factory Dining Room and La Côte Basque (2013), both recalling Wyeth’s New York City experiences. Never shown before, these two miniature compositions––painted and sculpted at one-sixth to life scale––connect Wyeth’s vision to a long tradition of surrealist and realist assemblage, and introduce yet another dimension of the imaginative worlds that inspire his creative process and, ultimately, his compositions.

Publication

The accompanying exhibition catalogue, Jamie Wyeth (MFA Publications; 2014) examines Wyeth’s work within a wide range of realist traditions––including those of his contemporaries and past American masters––giving particular attention to the multifaceted nature of the creative process over the course of the artist’s career. Written by Elliot Bostwick Davis, the MFA’s John Moors Cabot Chair, Art of the Americas, with an essay byDavid Houston, Jamie Wyethfeatures 208 pages and 143 color illustrations, and is available in hardcover for $50.

More images from the exhibition

More images from the exhibition