This fall, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), presents

Goya: Order and Disorder, a landmark exhibition dedicated to Spanish master Francisco Goya (1746–1828). The largest retrospective of the artist to take place in America in 25 years features more than 160 paintings, prints and drawings—offering the rare opportunity to examine Goya’s powers of observation and invention across the full range of his work. The MFA welcomes many loans from Spain and throughout Europe, including 21 works from the Museo Nacional del Prado in Madrid, along with loans from the Musée du Louvre, the Galleria degli Uffizi, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art (Washington) and private collections throughout Europe and the US.

Goya: Order and Disorder includes some 60 works from the MFA’s collection of Goya’s works on paper, one of the most important in the world. Many of these prints and drawings have not been on view in Boston in 25 years. Employed as a court painter by four successive rulers of Spain, Goya managed to explore an extraordinarily wide range of subjects, genres and formats. From the striking portrait

Duchess of Alba (1797) from the Hispanic Society of America, to the tour de force of Goya’s

Seated Giant (by 1818) in the MFA’s collection,

to his drawings of lunacy, the works on view demonstrate the artist’s fluency across media. On view in the Museum’s Ann and Graham Gund Gallery from October 12, 2014–January 19, 2015, the MFA is the only venue for the exhibition, which is accompanied by a publication revealing fresh insights on the artist.

As 18th-century culture gave way to the modern world, little escaped Goya’s penetrating gaze. Working with equal prowess in painting, drawing and printmaking, he was the portraitist of choice for the royal family as well as aristocrats, statesmen and intellectuals—counting many as acquaintances or friends. Living in a time of revolution and radical social and political transformations, Goya witnessed drastic shifts between “order” and “disorder,” from relative prosperity to wartime chaos, famine, crime and retribution.

Among the works he created—some 1,800 oil paintings, frescoes, miniatures, etchings, lithographs and drawings—many are not easy to look at, or even to understand. With a keen sensitivity to human nature, Goya could portray the childhood innocence of

Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga(about 1788, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

—his most famous portrait of a child—or the deviance of the

Witches' Sabbath(1797–98, Fundación Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid).

“This Goya exhibition brings together two very important strands of Santander’s identity, our commitment to New England and our heritage in Spain,” said Roman Blanco, president and CEO of Santander US. “We are delighted to join with the Fundación Banco Santander to sponsor the exhibition. We commend the MFA for bringing together this extensive collection of Goya’s work that is sure to inspire all who attend.”

“We thought it was fitting as the foundation representing Spain’s leading bank, to sponsor an exhibit that features the work of Spain’s leading painter,” said Antonio Escámez, Chairman of the Fundación Banco Santander in Madrid. “We are a global bank with a clear focus on the well-being of the communities where we operate. Supporting this exhibit is just one of the ways in which we show our commitment to Boston and the United States.”

The full arc of Goya’s creativity is on display in the exhibition, from the elegant full-length portraits of Spanish aristocrats that first brought the artist fame, to caustic drawings of beggars and grotesque witches, to his series of satirical etchings targeting ignorance and superstition, known as the Caprichos. Rather than a chronological arrangement, exhibition curators Stephanie Loeb Stepanek, Curator of Prints and Drawings, and Frederick Ilchman, Chair, Art of Europe and Mrs. Russell W. Baker Curator of Paintings, grouped the works in Goya: Order and Disorder, and its accompanying publication, into eight categories highlighting the significant themes that captured Goya’s attention and imagination. From tranquil to precarious, Goya’s art made the diversity of life, and the conflicting emotions of the human mind, comprehensible to the viewer—and to himself.

“We decided to juxtapose similar subjects or compositions in different media in order to allow visitors to examine how Goya’s choice of technique informed and transformed his ideas, since the characteristics of each medium—and the intended audience—influenced the final appearance of the work,” said Stepanek.

Noted for his satirical eye, Goya reserved his closest scrutiny for himself. The first section of the exhibition,

Goya Looks at Himself, is a sweeping group of self-portraits. In the MFA’s etching,

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (El sueño de la razon produce monstruos), Caprichos 43 (1797-99), Goya offers himself as a universal artist sleeping at a desk, while the creatures of his dreams swirl about his head. This print is grouped with two loans from Madrid,

The Artist Dreaming(about 1797), a drawing from the Prado that preceded the famous print, and

Self-Portrait while Painting (about 1795), from the Museo de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando.

Self Portrait with Doctor ArrietaFrancisco Goya y Lucientes (Spanish, 1746–1828)1820Oil on canvas*Lent by The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, The Ethel Morrison Van Derlip Fund*Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Together, these works reflect Goya’s tendency to insert his persona into allegories and fantasies. At the entrance of this section is an imposing group portrait of

T

he Family of the Infante Don Luis (1784, Fondazione Magnani Rocca, Parma, Italy)—the brother of King Charles III—which features 14 figures, including Goya, who depicts himself working on a sizeable canvas on an easel.

“Just as Goya’s imagery is determined by whether he painted, drew or made a print, he also reconsidered certain favored subjects, reviving them from his memory and returning to them again and again during his long career,” said Ilchman. “Examining his compositional preoccupations across decades—often in the same room of the exhibition—reveals the continuity of Goya’s imagination.”

Through his art, Goya sought to describe, catalogue and satirize the breadth of human experience—embracing both its pleasures and discomforts. The artist tackled the nurturing of children, the pride and infirmity of old age, the risks of romantic love, and all types of women—from young beauties to old women.

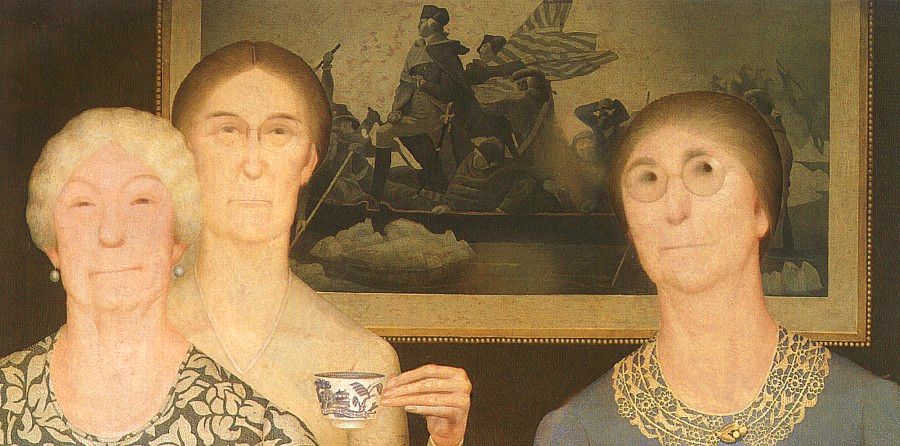

In the section dedicated to Goya’s depictions of the stages of life,

Life Studies, the exhibition explores how the artist transformed observations of human frailty, creating allegories of vanity and the passage of time. A wizened woman, who is unsuccessfully attempting to adopt youthful styles in

Until Death (Hasta la muerte), Caprichos 55 (1797–99, The Boston Athenaeum),

is revived in one of Goya’s most haunting monumental paintings—

Time (Old Women) (about 1810–12, Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille).

The aged woman is now decayed and diseased, but still clings to her outdated fashions, and is soon to be swept away by the broom of Time. Goya’s tapestry designs frequently depict young people, with relationships between men and women marked by affection, disaffection and tension.

The Parasol (1777, Museo Nacional del Prado)

presents a young woman who poses under a parasol with her docile lapdog—she seems to ignore her male companion in favor of engaging viewers who would look up at this tapestry, which was meant to hang over a door.

In the

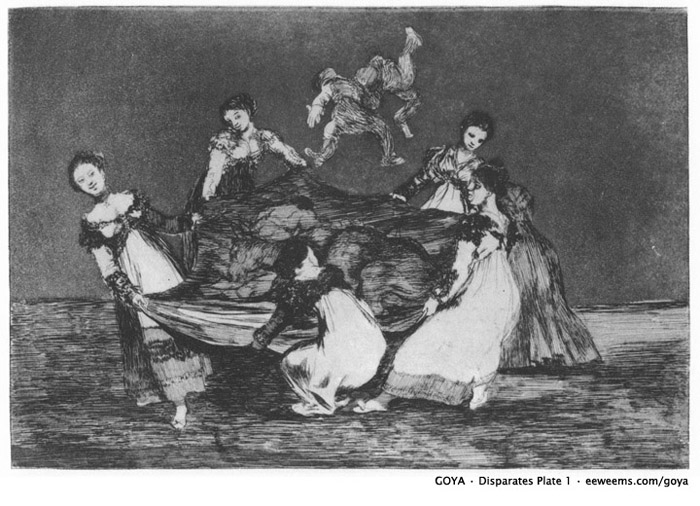

Play and Prey section, Goya’s creative process is revealed through representations of a popular game in which young women toss a well-dressed mannequin in a blanket. In

Straw Mannequin,

this carnivalesque reversal of class and gender roles is seen in a tapestry (1792–93, Patrimonio Nacional, Spain), as well as two preparatory paintings (1791, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles and Museo Nacional del Prado).

A late print,

Feminine Absurdity (Disparate femenino) Disparates 1 (1815–17, Fundación Lázaro Galdiano), imparts new meaning to the previously simple image of young women at play, as the women now strain to lift several figures, including a peasant and donkey. This more sinister vein is reflected in many of the subjects the artist returned to later in life, following the devastation of the Peninsular War and its political reversals. “Play and Prey” also explores Goya’s famous images of men engaging in hunting (his own favorite pastime) and the bullfight. In these works, including examples from the series of prints, the

Tauromaquia and the

Bulls of Bordeaux, Goya celebrates both activities while also subtly portraying their darker sides.

The precarious relationship between order and discord, balance and imbalance, is fundamental to Goya’s work, and the subject of the section

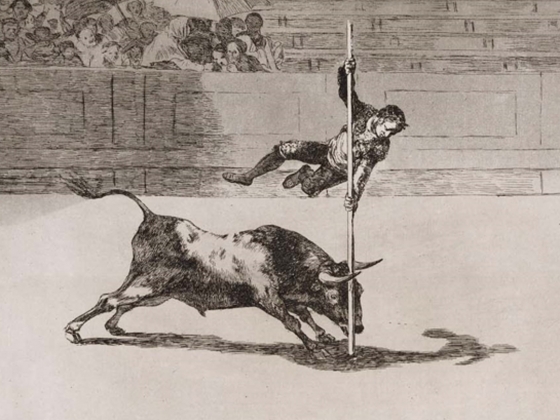

In the Balance. The theme appears vividly in images of the punishing forces of nature, figures losing their balance and others fighting. This topic is particularly noteworthy given the tumultuous social and political change during Goya’s lifetime, as well as the artist’s own struggles with illness, dizzy spells and deafness. The MFA’s print,

The Agility and Audacity of Juanito Apiñani in the Ring at Madrid (Ligereza y atrevimiento de Juanito Apiñani en la de Madrid (Tauromaquia 20) (1815–16) depicts a precarious matador, who is poised midair as he vaults over a charging bull, anchored only by his upright pole.

Goya earned widespread fame through grand portraits executed in the 1780s and 1790s, and the exhibition displays some of these masterpieces alongside more intimate likenesses of his artistic and family circle. Focusing on the painter’s approach to portraiture—from relations with sitters to his handling of paint—

Portraits explores the discipline that remained central to his reputation as Spain’s leading painter and helped sustain him financially throughout his career. Paintings of the

Duke of Alba (1795, Museo Nacional del Prado) and

Duchess of Alba (1797, Hispanic Society of America),

shown together for the first time since the early 19th century, are superb examples of his aristocratic portraits and illustrate two of his most important patrons. In the

Duchess of Alba, the darkly clothed sitter points a finger to the ground, where the words “Solo Goya” are written in the sand. The assertion that only Goya was worthy of this commission and that only he could have pulled off such a dramatic likeness, changes the painting’s focus from the aristocrat to the artist.

Other Worlds, Other States features two facets of Goya’s spiritual explorations—Christian religious belief and its opposite, superstition. While Goya frequently focused on clerical abuses, religious commissions helped pay the bills throughout his life, and there is no evidence that he lacked personal piety. One of Goya’s greatest legacies is his ability to represent mental and psychological conditions. His depictions of illusions and inner reality are also on view in this section, and include visions, nightmares and the deluded mind of the insane. An imaginative rendering of a particular Spanish nightmare—a witch riding a bull through the air—is depicted in the drawing

Pesadilla (Nightmare) (1816-1820).

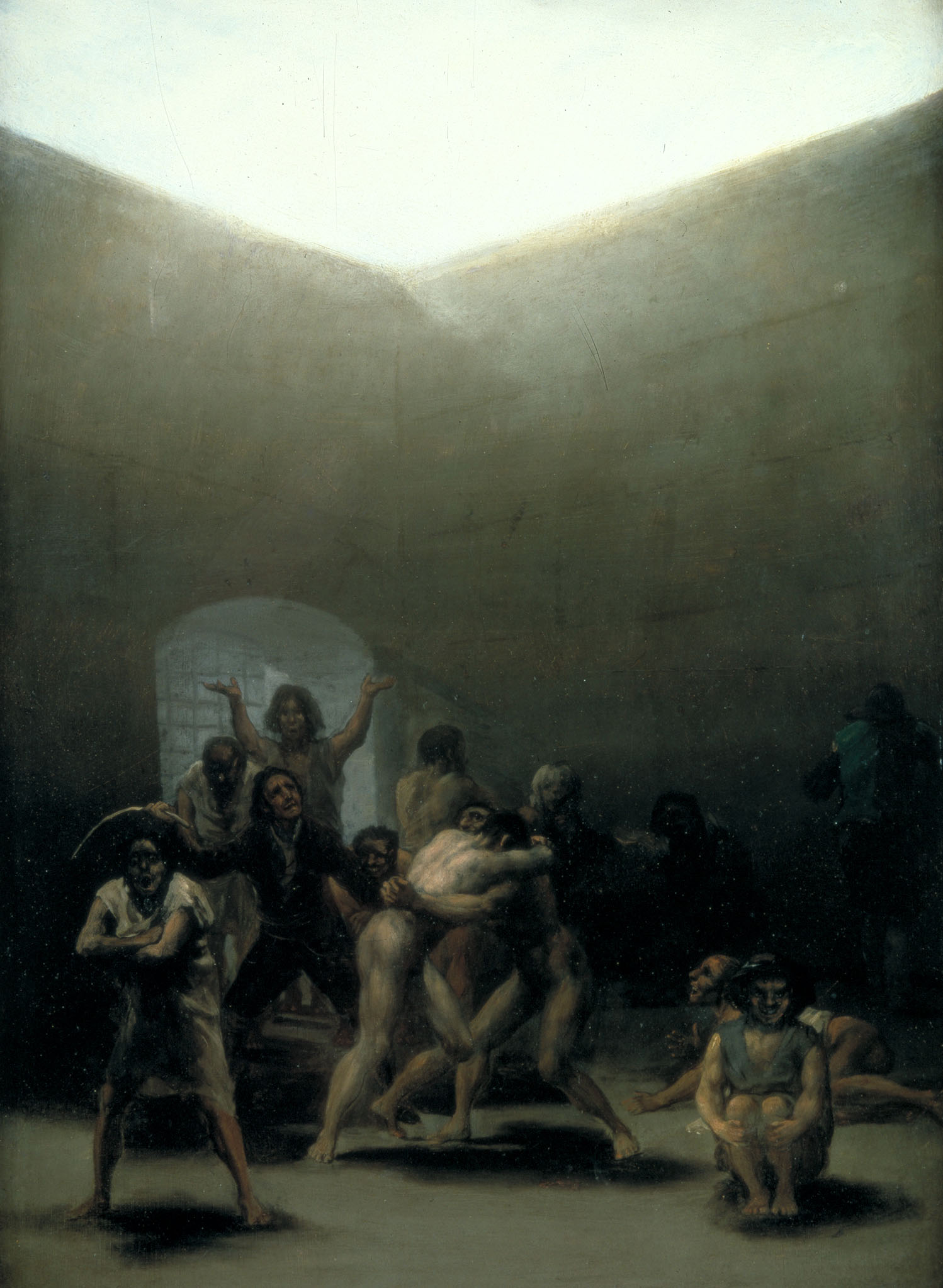

Many of Goya’s deranged characters highlight the fragile boundary between lunacy and sanity. A luminous painting on copper from the Meadows Museum in Dallas,

Yard with Madmen of 1794

—which shows distressed and helpless lunatics—anticipates a sequence of black crayon drawings made three decades later. In these later works, the individuals, whom Goya labeled as “locos,” are in even more desperate condition, restrained in straitjackets or trapped behind bars. Also in this gallery, a “learning space” offers additional educational materials and a timeline that provides context and insight into the mind of the Spanish Master.

A keen awareness of the weight of historical events pervades Goya’s work. Although he belongs in the ranks of great history painters who narrated courageous acts, he is not preoccupied with generals, patriots and battles. Instead, he focuses attention on the anonymous victims of the horrors of war or the Spanish Inquisition, and rarely fails to raise moral questions in these works. In

Capturing History, works that blend the epic and mundane include a painting of an imagined scene,

Attack on a Military Camp (about 1808–10, Colección Marqués de la Romana),

in which a woman holds a screaming infant as she runs from assailants who have already wounded several people. In

One Can’t Look (No se puede mirar,) Disasters of War 26 (1810–14),

the viewer is only a step or two away from the victims and the advancing bayonets of the print’s aggressors. The work is part of the wrenching print series,

Disasters of War, which depict the artist’s thoughts on violence during the Peninsular War that ripped Spain apart from 1808 to 1814.

The final section of the exhibition,

Solo Goya, summarizes the characteristics that establish the artist’s greatness—exploring themes such as Goya’s imagery of swarms of human figures as well as his periodic reflection on the concept of redemption. The same artist who took on the abuses of war could also evoke the most sympathetic and poignant moments of human experience, such as the

Last Communion of Saint Joseph of Calasanz (1819, Collection of the Padres Escolapios).

The altarpiece depicts Joseph of Calasanz, from Goya’s home region of Aragón, who founded the order of the Padres Escolapios (Piarists) to educate poor children. Goya may have attended one of the order’s schools, known as the Escuelas Pías, and might have felt a personal connection to the protagonist of the painting—his final major religious work—which comes to the US for the first time in this exhibition.

One of Goya’s most resonant themes addresses the problem with power, embodied by a central character: the giant. Conditioned by the events of his day, particularly the sudden rise and fall of military and institutional fortunes, Goya explores how power is not necessarily inherent, but comes with a cost. Goya’s Seated Giant (by 1818), from the MFA’s renowned collection of Goya prints and drawings, is among the most enigmatic and compelling of the artist’s graphic works, depicting a looming figure immobilized by the burden of power. While no single work can epitomize an artist’s achievement, this figure embodies the grandest of Goya’s great themes.

The MFA’s Goya collection owes a great debt to former MFA Curator of Prints and Drawings, and esteemed Goya scholar, Eleanor A. Sayre, who worked on the exhibitions T

he Changing Image: Prints by Francisco Goya (1974) and

Goya and the Spirit of Enlightenment (1989) at the MFA. Many of the works on view in

Goya: Order and Disorder were acquired by the Museum during her tenure, including the

Seated Giant;

Woman Reading to Two Children (about 1819);

Resignation (La resignacion) (1816–1820);

Merry Absurdity (Disparate alegre) (1816–1819); and the oil sketch on canvas of the

Annunciation (1785).

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (El sueño de la razon produce monstruos), Caprichos 43 (1797–99)

and the drawing of

Two Men Fighting (1812–20) were part of Sayre’s bequest to the MFA after she passed away in 2001.

Member Preview Days

MFA members will be the first to see Goya: Order and Disorder during Member Preview Days, October 7–11. Members always visit free and never need a ticket to see the MFA’s collections and exhibitions. For more information on membership, please go to

mfa.org/membership/levels-and-benefits.

Lectures and Courses

Visitors can learn more about Goya and the art of Spain with a number of fall lectures and courses at the MFA. From October through December, a diverse 10-week course features curators, scholars and performers exploring Spanish art and culture from the medieval era through the early 20th century. The Barbara and Burton Stern Lecture on Sunday, December 7, offers

Reflections on Goya’s Drawings with Manuela Mena Marqués (chief, 18th-century paintings conservation and Goya, Museo Nacional del Prado). On

Sunday, December 14, visitors can experience two 18th-century powerhouses when the music of Ludwig van Beethoven, performed by New England Conservatory faculty and students, is joined by projections of works by Goya. The MFA’s newest program,

Remix, will include a tour of

Goya: Order and Disorder with MFA curator Frederick Ilchman before sampling Spanish wines and tapas on October 24. Additionally, an array of “Looking Together” sessions—in-depth, interactive gallery experiences—offers insight into Goya, Spanish art and the Museum’s collection with MFA educators.

Publication

The exhibition is accompanied by the publication

Goya: Order and Disorder (MFA Publications; 2014), which is the first consideration of Goya’s works in all media through a non-chronological, thematic approach. Written by MFA curators Frederick Ilchman and Stephanie Loeb Stepanek and world-renowned Goya expert Janis A. Tomlinson, with contributions by Clifford S. Ackley, Jane E. Braun, Manuela B. Mena Marqués, Gudrun Maurer, Elisabetta Polidori, Sue Welsh Reed, Benjamin Weiss and Juliet Wilson-Bareau, the 400-page book includes 260 color illustrations and is available in hardcover ($65).