The

Art Institute of Chicago has announced the largest gift of art in the museum’s

136-year history: the Edlis/Neeson Collection, 42 iconic masterpieces of

contemporary art donated by the Chicago-based collectors and philanthropists

Stefan T. Edlis and his wife, Gael Neeson. The gift includes nine works by Andy

Warhol, three paintings by Jasper Johns, one Robert Rauschenberg Combine, two paintings

by Roy Lichtenstein, four paintings by Gerhard Richter, and a painting and

sculpture by Cy Twombly. Works by Brice Marden, Eric Fischl, Jeff Koons, Damien

Hirst, Charles Ray, Takashi Murakami, Katharina Fritsch, Cindy Sherman, Richard

Prince, and John Currin complete the exceptional gift.

The

Edlis/Neeson Collection includes an outstanding selection of internationally

recognized masterpieces that capture the collectors’ passion for art created at

mid-century and beyond: the important work that paved the path to Pop Art,

Warhol and the full flowering of the movement, and its imprint on later

artists.

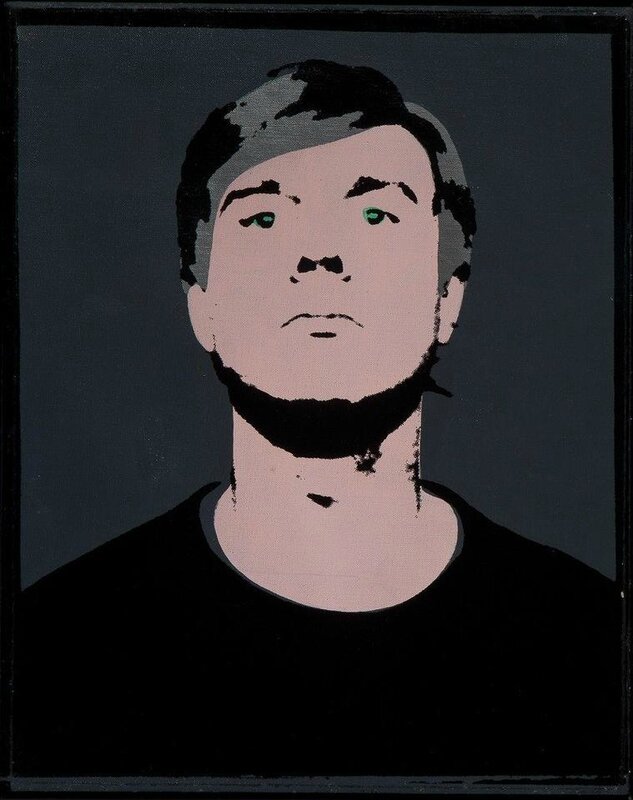

The heart of the collection is nine works by Andy Warhol,

Andy Warhol, "Self-Portrait", 1964. The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Edlis/Neeson Collection.

The heart of the collection is nine works by Andy Warhol,

Andy Warhol, "Self-Portrait", 1964. The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Edlis/Neeson Collection.

Twelve Jackies (1964),

Big Electric Chair ( 1967–68),

and the later works

Mona Lisa Four Times (1978)

and Pat Hearn (diptych) (1985).

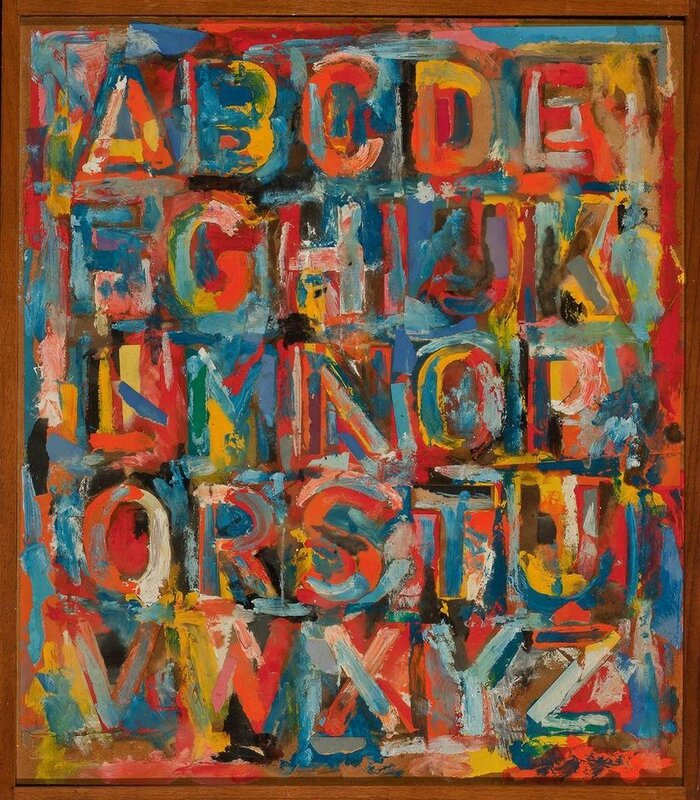

Jasper Johns is represented by three archetypal paintings: Target (1961) (see below)

Figure 4 (1959), and

Alphabet (1959).

Two later Roy Lichtenstein paintings—

Artist’s Studio “Foot Medication” (1974)

and Woman III (1982)

—trace the legacy of Pop Art into the 1970s and 1980s, a story carried into sculptures by Jeff Koons, included here with Christ and the Lamb (1988) and

Bourgeois Bust–Jeff and Ilona (1991).

Works by Gerhard Richter from both the 1960s (Hunting Party and Stadtbild) and the 1980s (Davos and Venedig) offer a view into his evolution as a painter and complement the Art Institute’s own rich holdings of Richter.

The revival of figurative painting is also a part of the collection, seen in Eric Fischl’s Slumber Party (1983) and John Currin’s Stamford After Brunch (2000).

Twelve photographs—six by Richard Prince and six by Cindy Sherman—touch on the gender and identity issues critical to art from the 1980s and beyond.

The Edlis family—a widowed mother and her three children, Lotte (18), Stefan (15), and Herbert (3)—arrived in the United States from Vienna in March 1941. Their journey from their home in Austria had begun four weeks earlier and took them via train through occupied France and Spain, then via ship from Lisbon to a midtown pier in Manhattan. Another branch of the family had been prominent members of Pittsburgh society since the turn of the century, and Edlis’s cousin Jerome provided the necessary guarantees and used his connections to urge the Viennese consul to ensure the European refugees residence, which was very difficult to obtain due to the immigration quota system. They settled in New York with Edlis’s mother’s family, and though their resources were few, jobs were plentiful and it was a happy upbringing.

At the age of 18, Edlis was drafted into the United States Navy and served in the Pacific. At the end of World War II, he found himself with a military discharge and a girlfriend in San Francisco, making a life in the Bay Area. While there, he worked in a small shop that pioneered the molding process of newly developed plastic compounds—a position that began his career in plastics manufacturing. He moved to Chicago in 1950 and at 25 memorably claimed to be 35 and a plant manager to land a position (which understandably did not last long). Fifteen years later, he had acquired enough experience, capital, knowledge, and customers to build the small but highly profitable Apollo Plastics Corporation, which he sold to a former business associate in 2000. It is still operating successfully in the same location under the leadership of the associate’s sons.

Edlis and Neeson directed those same energies into their shared passion for arts and culture, not only building a deep private collection but also being active patrons of Chicago’s cultural community. Edlis has been a life trustee and leading donor at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago for decades, where he and his wife have donated iconic works of art, named the Edlis Neeson Theater, and established a major acquisitions fund.

Jasper

Johns. Target, 1961.

By incorporating found images and objects into his work in

the 1950s and early 1960s, Jasper Johns was a catalyst in the shift away from the

visual and critical dominance of Abstract Expressionist artists. The

Edlis/Neeson gift includes three seminal Johns works from this era—Figure

4(1959), Alphabet(1959), and the iconic Target(1961). Target is an example of

one of Johns’ most recognizable and important motifs and captures the play

between art, object, and sign that would pave the way for Pop Art.

Robert

Rauschenberg. Untitled, circa 1955.

Robert Rauschenberg is represented in the

gift to the Art Institute by Untitled (1955), one of the most significant Combines

of his career. The Combines—hybrids of painting and sculpture incorporating

found materials and images—challenged the two-dimensional limits of the canvas

and attempted to bridge what Rauschenberg called “the gap between art and life.”

This pivotal piece belonged to Jasper Johns for decades; the string hanging

from the toy parachute is argued to have inspired Johns’ Catenary series.

One of fourteen large canvases

that Twombly produced by himself in the isolated Palazzo del Drago north of

Rome during August and September 1969, Untitled (Bolsena )is both abstract and

cryptically graphic—a crucial example ofa transitional moment in

twentieth-centuryart. The gift will also include Twombly’s sculpture Untitled(1953),

which Edlis and Neeson acquiredfrom the collection of Robert Rauschenberg. That

sculpture is widely acknowledged as among the artist’s most important objects.

Andy Warhol. Liz#3 [Early Colored Liz], 1963. The Stefan T. Edlis Collection,

Partial and Promised Gift to the Art Institute of Chicago.

Andy Warhol is

represented by nine iconic paintings, including two self-portraits;exemplary

images of Jacqueline Kennedy, Liz Taylor, and the Mona Lisa;and a definitive

electric chair. This gift allows the Art Institute to now claim the best

collection of Warhol’s work in any encyclopedic museum in the world.

The Edlis/Neeson Collection includes works by

artists such as Cindy Sherman who, inheriting the formal and conceptual

strategies of Pop Art, applied them to mass culture in innovative ways. Six

works from Sherman’s most important series, the Centerfolds(1981), join six

“appropriations” by Richard Prince to form a portfolio of contemporary

photography within the gift.