Rolling Hills, Satanic Mills: The British Passion for Landscape, a major traveling exhibition drawn from the remarkable collections of Amgueddfa Cymru–National Museum Wales and organized by the American Federation of Arts, opens at the Frick Art & Historical Center in Point Breeze on May 9, 2014.

Rolling Hills, Satanic Millst races the development of landscape painting in Britain through the Industrial Revolution and the eras of Romanticism, Impressionism, and Modernism, to the postmodern and postindustrial imagery of today. More than 60 works of art—including major oil paintings, watercolors, drawings, and photographs—offer fresh insight into the changing relationship between artists and the landscape, as well as the evolving tastes of wealthy collectors.

Beginning with Old Masters ClaudeLorrain (1604–1682) and Salvator Rosa (1615–1673), the exhibition features an international roster of artists, from famed British painters Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797), John Constable (1776–1837), Thomas Gainsborough 2(1727–1788), and J. M.W. Turner (1775–1851), to Impressionists Claude Monet (1840–1926) and Alfred Sisley (1839–1899).

The exhibition title, Rolling Hills, Satanic Mills, is an adaptation of lines from William Blake’s 1804 poem “Jerusalem,” in which poet/artist Blake contrasts the green rural landscape of Britain with the newly emerging industrial cities. Although drawn from a Welsh collection and depicting mainly British subjects, many parallels can be drawn between the rolling hills and satanic mills of Great Britain and the peaks and valleys of industrial Pittsburgh. In addition, institutional collections in Pittsburgh and in Cardiff were similarly shaped by the artistic passions of 19th-century collectors, often men who had made their fortunes through industry.

Rolling Hills, Satanic Mills: The British Passion for Landscape provides a rare opportunity for Pittsburghers and the larger Western Pennsylvania regional audience to see these remarkable paintings outside their home at National Museum Wales.

Broadly chronological, the exhibition is divided into six thematic sections, unfolding a story that runs from the Industrial Revolution through the eras that saw the emergence of Romanticism, Impressionism, and Modernism, to the postmodern and postindustrial present.

The first section,

Classical Visions and Picturesque Prospects, explores the 17th-century origins

of landscape painting, including works by two of the fathers of the

genre—Claude Lorrain and Salvator Rosa—along with some distinctly British

responses to these 17th-century models. Thomas Gainsborough (1726–1788), like

other artists, was influenced by Claude’s calm, balanced landscapes—graceful

trees frame vistas that dissolve into soft horizons, creating spaces for

relatively diminutive figures to enact scenes from the Bible, Classical

history, or peasant life.

Rocky Wooded Landscape with Rustic

Lovers, Herdsman, and Cows

(1771–74), lush trees frame an idyllicized vision of rural life, creating a

romantic vision of the charms of the country.

Watercolor, a medium

previously used mainly for preparatory works, came into its own with the rise

of landscape painting as artists increasingly valued the spontaneity of

sketches made on the spot.

A section of the

exhibition, Turner and the Sublime,

features six works by Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851), often

considered the greatest of British landscape artists. Turner’s work is shown in

the context of the Romantic movement and that era’s interest in sublime

experience. Artists working in the Romantic style embraced a subjective and

emotional response to nature. Turner began his career at a young age, making

topographical and architectural illustrations, yet became one of the most

innovative and distinctive creators of landscape in art history. An

indefatigable traveler, Turner sketched and worked in watercolor, capturing his

immediate response to the landscape. Four watercolors illustrate his consummate

skill with the medium and convey a sense of freshness and immediacy.

Two oils,

and The Morning after the Wreck (c. 1840),

demonstrate his

virtuoso style, which has been described as foreshadowing both Impressionism

and abstraction. These emotionally powerful landscapes represent the period’s

interest in evoking the sublime through the grandeur and power of nature and

the smallness of man.

For artists

interested in the sublime, intimations of mortality, destruction, and terror

lived side-by-side with beauty, and were meant to evoke astonishment and wonder

in the viewer. Truth to Nature focuses

on the British interest in the direct and detailed depiction of the natural

world.

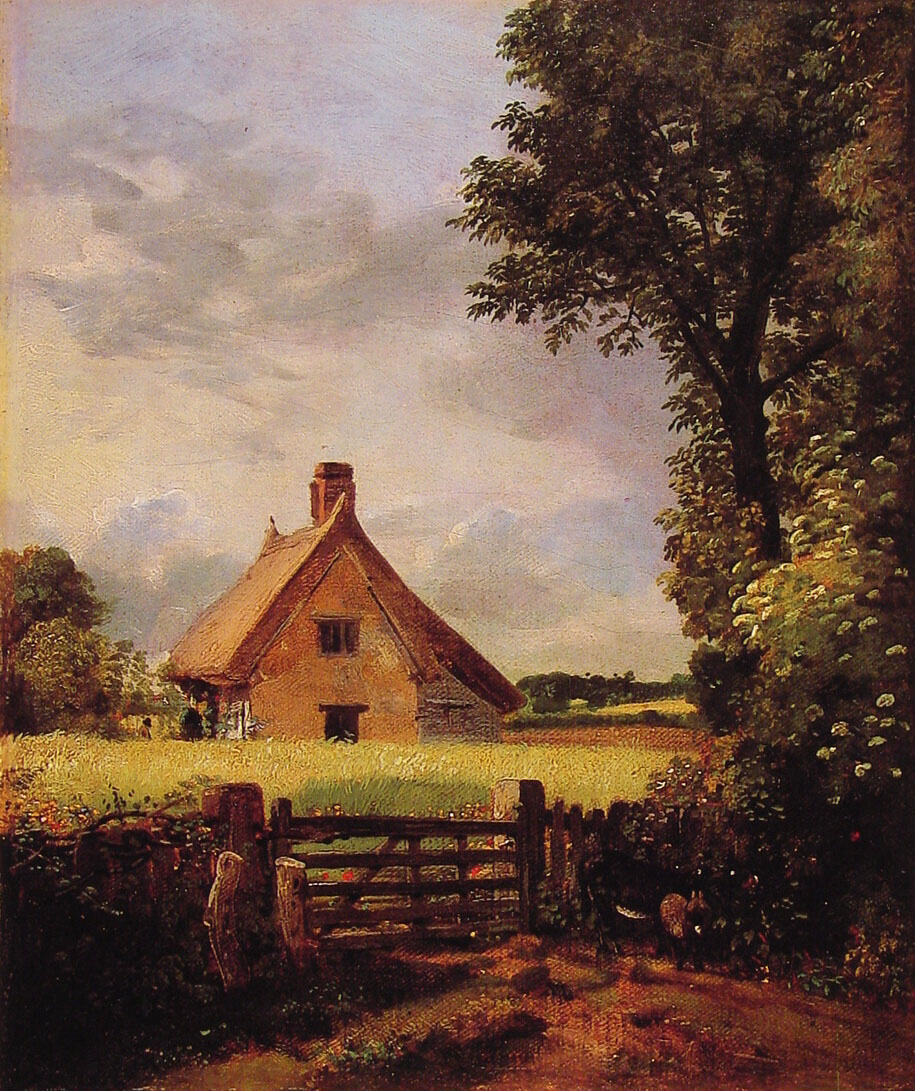

In the celebrated

A Cottage in a Cornfield 1817), John Constable pays tribute to

his native East Anglia, finding poetry in the details of rural scenery and

capturing with uncanny exactitude momentary shifts in the cloudscape of

Suffolk.

The 1840s saw the

emergence of photography, and soon the accuracy of representations provided by

the camera—the “pencil of nature”—became a powerful stimulus to landscape

artists. Artists viewed the world with a new precision, bringing scientific

objectivity to their compositions.

Snowdon from Llanfrothen (1938) attests.

Picturing Modernity looks at artistic depictions of the changing

landscape in tandem with the growth of cities, revealing new ways of life

experienced by an increasingly urbanized population. From the earliest days of

industrialization, artists such as Paul Sandby and John “Warwick”

Smith were captivated by the strange and unprecedented world of machinery found

in mining, iron forging, and textile manufacturing, which were the basis of Britain’s

prosperity. Cardiff had become a major industrial and port city by the

mid-19thcentury, and remains so today. Portrayals of industry often echo the

themes found in the dramatic landscapes of the Romantics. Tumultuous,

smoke-filled skies create opportunities for painterly light effects and for

commenting on the contrast between the works of man and those of nature.

The only American

artist in the exhibition, Lionel Walden, captures the drama of industry in his

nearly 5-foot-wide canvas

Steelworks, Cardiff, at Night (1895–97).

Straightforward

documentary paintings—sometimes depicting the views from the windows of

artists’ studios—convey the marvelous spectacle of the metropolis. This

celebration of modernity continued into the 20th century, with works like

Viennese Expressionist Oskar Kokoschka’s powerful depiction of the Thames in London, Waterloo Bridge(1926).

Viennese Expressionist Oskar Kokoschka’s powerful depiction of the Thames in London, Waterloo Bridge(1926).

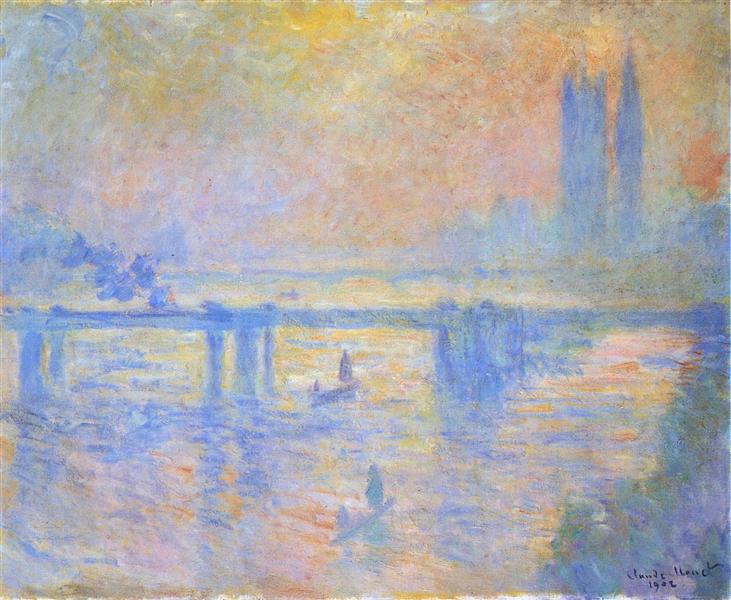

During a period of

enforced exile in England precipitated by the Franco-Prussian War, Claude Monet

made the Thames his own. Included in the section Monet and Impressions of Britain,

The Pool of London (1871) captures with remarkable

boldness the gray tonalities and surging energy of one of the busiest ports in

the world, a great hub of commercial activity. After returning to London in

1899, Monet painted the visionary

Charing Cross Bridge (1902) from a fifth-floor balcony at

the Savoy Hotel. He was a great admirer of London’s fogs, the result of

industrial pollution, and his swift brushwork mimics the scudding movement of

the clouds and the smoke of a train crossing Hungerford Bridge.

With the foreboding

international climate of the 1930s, landscape came to symbolize all that was

valued in British culture. A group led by Graham Sutherland and John Piper

espoused Neo-Romanticism, a return to the traditional subjects of Constable and

Turner inflected with the experience of modernism. The resulting work was often

brooding in tone.

Through an ongoing series of drawings, photographs, and sculpture, David Nash has chronicled his efforts to create organic sculpture from living, growing trees, which he planted at Ffestiniog in Wales in 1977. His work is an intervention in the landscape and a powerful statement against deforestation, harking back, ultimately, to the rural world that preceded the industrial era. With these haunting works, we are reminded of the powerful connection to the land that was the genesis of landscape art. Artists working with the landscape today are sensitized to the imprint of man on the planet, and their work—while sometimes hard to categorize as conceptual art, performance, photography, or sculpture—springs from the same attachment to the land that has led artists out-of-doors for hundreds of years.