6 APRIL - 1 AUGUST 2016

The Centre Pompidou is proposing a journey through the

work of a singular figure in modernity and one of the

20th century’s most iconic artists: Paul Klee. This is the first major in

France since the 1969 exhibition at the Musée National d’Art Moderne.

Featuring two hundred and thirty works loaned by the

Zentrum Paul Klee in Bern

and various major international and private

collections, this retrospective casts a fresh look

on Klee’s work. It sheds

light on the way he used irony through an approach originating in the early

German Romanticism, consisting in a constant shift between a satire and the

affirmation of an absolute, finite and infinite, real and ideal. In this

respect, Klee’s use of irony is inspired by the philosopher Friedrich Schlegel:

«Everything in it must be a joke, and everything must be serious: everything

must be offered up with an open heart, and profoundly concealed.»

This new

approach also explores Klee’s relationship with his peers and the artistic

movements of his time.

The exhibition is divided into seven thematic sections

highlighting each stage in Klee’s artistic development:

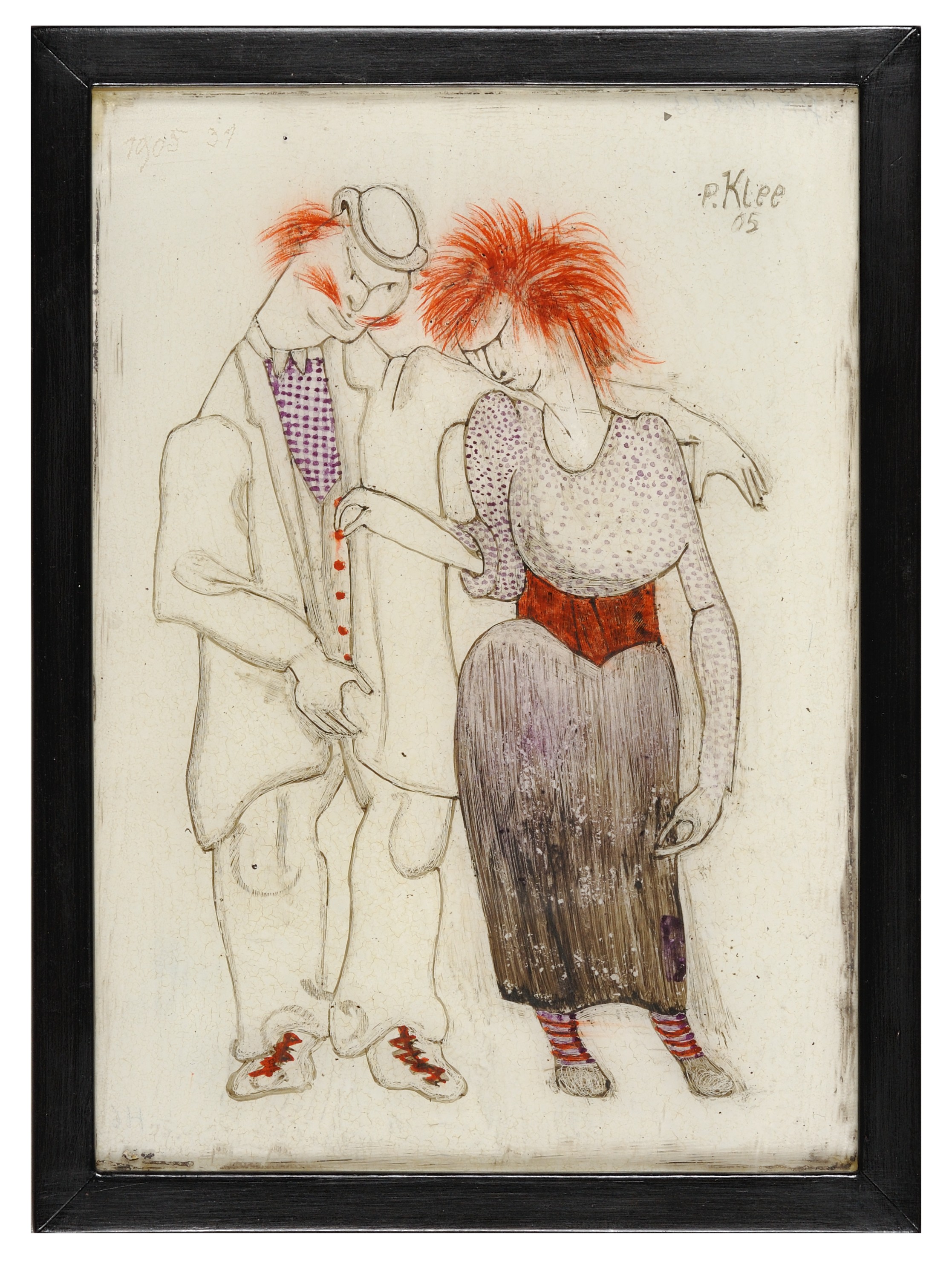

I. Satirical beginnings

After his studies in Munich, Klee spent the winter of

1901-1902 in Italy. Faced with the grandeur

of Antiquity and its Renaissance,

the young artist became aware of his own place in history: that

of an imitator

obliged to continue a now outmoded classical idealism. His solution was satire:

a modern mode of expression that could assert both high ideals and a critical

view of the state of the world.

« I serve beauty by depicting its enemies

(caricature and satire) », he wrote in his diary.

Based on this dialectical

inversion central to Romantic irony, Klee began producing essentially graphic

works, in which he expressed his often scathing thoughts on relations between

the sexes, his relationship to society and his position as an artist. It was

also a time when he experimented with techniques, trying out reverse glass painting

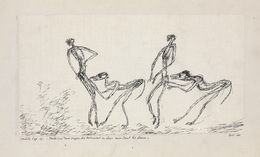

and exploring plastic forms. This period culminated in the illustrations

for Candide

ou l’Optimisme by Voltaire, a writer much venerated by Klee.

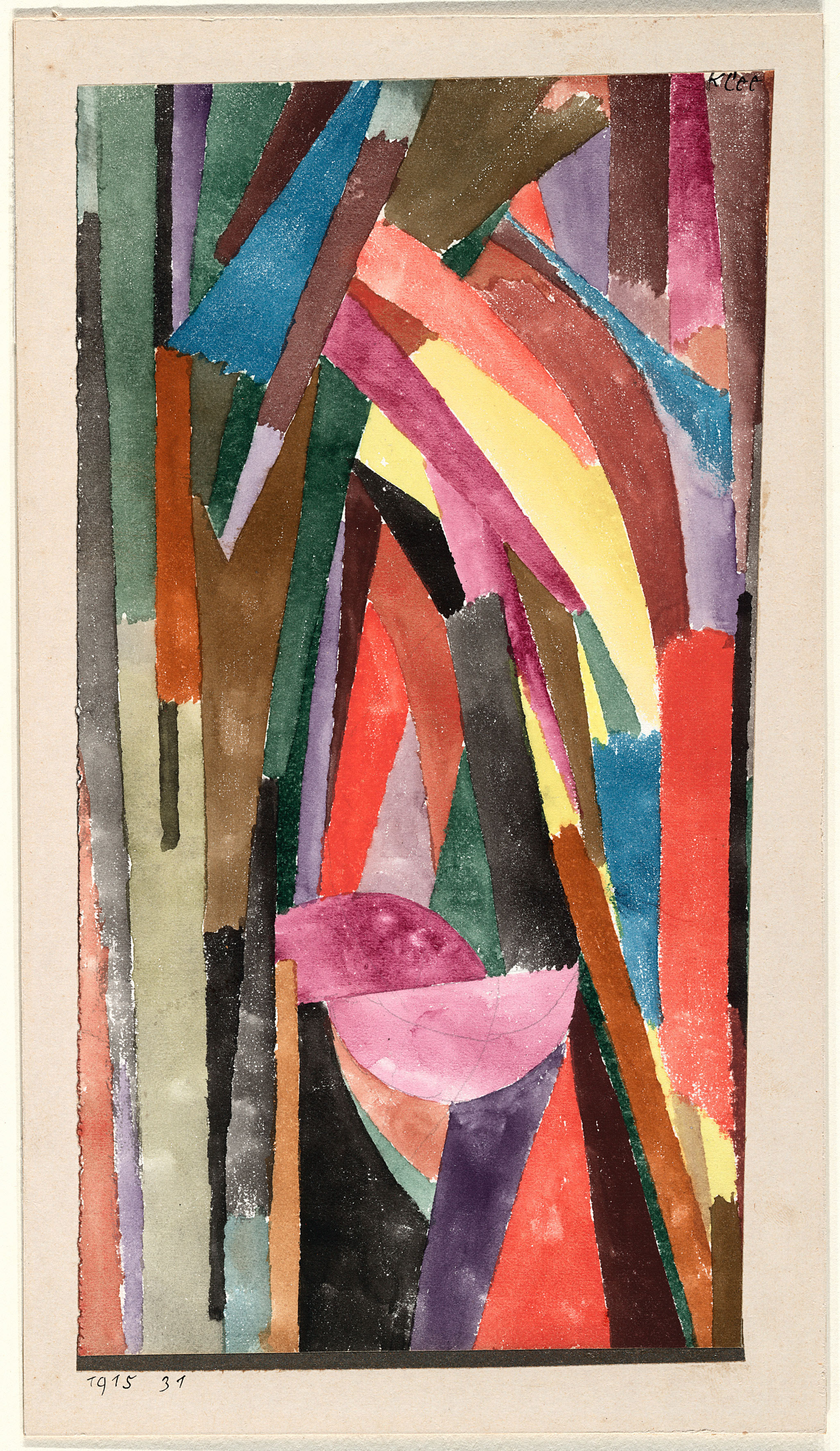

2. Klee and Cubism

Klee discovered Cubism in Munich in late 1911, and a

year later during his stay in Paris. From then on, the formal inventions of

Cubism nourished his pictorial explorations, often in a dialectical way. Whilst

using a prismatic vocabulary, Klee’s childlike drawings are nevertheless an

ironic representation of the Cubist decomposed figures that he found deprived

of all vitality. In the series of watercolours painted during his formative

stay in Tunis in 1914, he introduced effects of distance – for example by

leaving

the vertical bands of white paper that corresponded to the marks left

by the elastic bands he used when painting outdoors. This distancing technique

was also evident in his highly singular approach, where

he cut up finished compositions into two or more parts,

turning them into independent works

or combining them differently on new

supports. Here Klee asserted a creative impulse whose roots lay paradoxically

in the act of destruction.

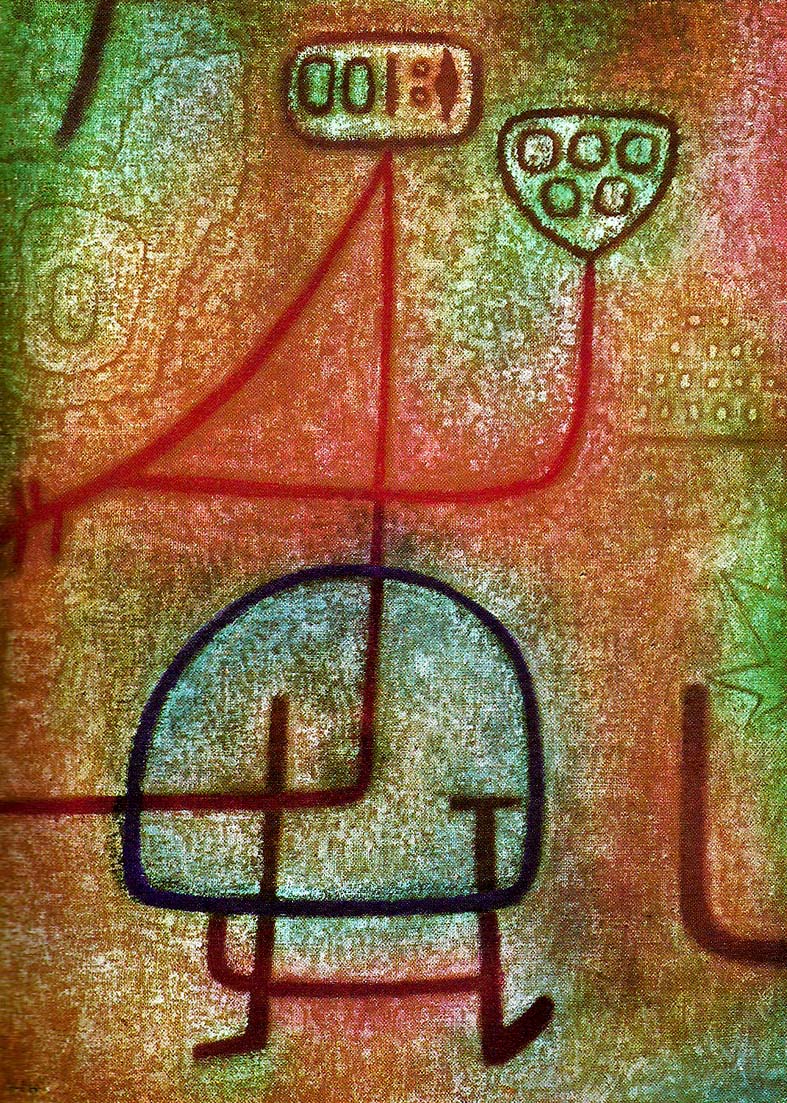

3. Mechanical theatre

At the end of the First Wold War, Klee’s work began to

feature the imagery of mechanised figures. Inspired by his experience in

aviation maintenance, Klee transformed birds into planes, often in attack

formation. He started using oil transfers: an indirect technique that

depersonalised the lines of the drawing. The aesthetics of the machine were

then much in vogue in Dadaist circles, from Francis Picabia to Raoul Hausmann.

Klee’s contact with the Zurich Dadaists revived his interest in the

representation

of machines and equipment, and the effects produced by their

mechanisms. As a teacher at the Bauhaus, he began to create hybrid beings,

half-human, half-object. Through mechanical simplification, he used the motifs

of automatons and puppets to condemn the loss of vitality and the narrowing of

inner life brought about by industrial rationalisation, asking ironically «

When will machines start bearing children? »

4. Klee and Constructivisms

The new watchword proclaimed in 1923 by Walter Gropius,

the founder of the Bauhaus («Art and technology: a new unity») marked a turning

point for the school. Klee was highly responsive to it.

He then embarked upon a

tightrope act, seeking a balance between his intuitive approach and the new

contemporary dogmas. He took up certain aspects of modernist expression such as

the grid, while sidestepping its rigidity. His paintings, structured by squares,

in turn evoked musical rhythms, stained glass painting, tapestries,

multi-coloured flowerbeds and aerial views of fields. The Bauhaus’s move

to the

modern city of Dessau in 1925 further induced the school’s movement towards the

use

of photographic techniques, ardently supported by its new teacher, László

Moholy-Nagy. Klee reacted in his own way: rational aesthetics acted as a foil,

enabling him to assert his antagonistic position more firmly. In his view,

«laws should only provide a basis for self-fulfilment.»

5. Backward glances

In his last years at the Bauhaus, Klee began to multiply

references to different epochs of the past. Inspired by his travels and the

many books and articles he read on the subject, he introduced pictorial

elements reminiscent of ancient mosaics, Egyptian civilisation and figures and

signs carved on the walls of Palaeolithic caves. The prehistoric dimension in

itself was a recurrent component in his imagination: fossils, caves, mountains

in the process of forming, primitive plants and animals, sacred stones,

undecipherable inscriptions on rocks and such like all allude to the past in

varying degrees. Klee used imitation as a method of appropriation. The

reproduction of the effects of time on both the object (wear and tear, mould,

erosion) and its content imbued his works with a sense of parody. While Klee

drew

on the repertory of signs produced by «primitive» or non-Western cultures,

he was only imitating

the principles of their original structure.

6. Klee and Picasso

Picasso represented a particular challenge for Klee. His

work dialogued with the Spanish artist’s with particular intensity at two

periods in his life: at the beginning of his career in around 1912, and above

all during the 1930s, after he saw the 1932 retrospective at the Kunsthaus in

Zurich. Here Klee discovered Picasso’s « Surrealism », particularly his large

paintings of female figures and his biomorphic metamorphoses: two new

directions that powerfully influenced Klee after the Bauhaus period, and stimulated the work of his final years.

This

confrontation was nourished by the publication of numerous articles on Picasso

in reviews such as Les Cahiers d’Art, to which Klee subscribed. After

his first visit to Picasso’s Paris studio in 1933,

the two artists met up at Klee’s

house in Bern in 1937. That virtually silent moment revealed the tensions

between these two giants of modernity. Their dialogue was imaginary, made up of

appropriation

and opposition, of secret admiration and critical irony.

7. The crisis years

Hitler’s coming to power in 1933 marked the end of

Klee’s career in Germany and forced him into exile in Bern. He responded with a

series of drawings that transposed the country’s predominant angst into violent

cross-hatching. Von der Liste gestrichen [Struck from the list], a

self-portrait in the form

of a pseudo-Cubist African mask, treats Nazis

politics with irony by parodying their own criteria

for exclusion. Klee liked to counter terror through a

childlike, playful iconography, where signs are transformed into stickmen

dancing not in joy but in fear. These figures may well allude to the general

physical training encouraged by the Nazis. Their dislocated appearance

reflected another source

of anxiety for the artist: the serious illness that

was beginning to stiffen his bodily movements. In 1935, Klee developed

scleroderma, a wasting disease that gradually mineralised his body. As a

result,

he simplified his graphic language, which now expressed

contemporary suffering – both humanity’s and his own – with elementary force.

Exhibition catalogue

by Angela Lampe

A publication with 312 pages and 300

illustrations, featuring new articles by internationally recognised Paul Klee

specialists. Format: 23.5 x 30 cm. Hardback. Price: €44.90.

From his satirical beginnings to his reinterpretation of

Cubism, productive exchanges with Dada

and inversion of the Bauhaus dogmas to

his final years of crisis, throughout his career Paul Klee endeavoured to

assert total freedom with regard to the modernisms of his time, readily taking casting

an ironic eye on their principles and disrupting their systems. The

retrospective staged by the Centre Pompidou Paul Klee takes a completely new

look at his entire output through the prism of Romantic irony. This

richly-illustrated catalogue contains contributions from leading specialists on

Klee and sheds light on the subversive character of his work.

PAUL KLEE Paul Klee, Ohne Titel (Zwei Fische, zwei Angelhaken, zwei Würmer Pen and watercolour on card 16,2 x 23,2 cm

PAUL KLEE Verkommenes Paar Couple mauvais genre, 1905 Reverse glass painting 18 x 13 cm Zentrum Paul Klee, Berne © Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE Candide, chapitre 16: Tandis que deux singes les suivaient en leur mordant les fesses, 1911 Pen on paper on card 12,7 x 23,6 cm Zentrum Paul Klee, Berne © Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE (Lustig?) [Lachende Gothik] [(Drôle?) [Gothique joyeux]], 1915 Watercolour and pastel on paper, metallic paper borders on card © Adagp, Paris 2016

28,9 x 16,5 cm The Museum of Modern Art, New York © 2016. Digital Image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence © Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE Vorführung des Wunders Présentation du miracle,1916 Gouache, pen and ink on prepared fabric, mounted on card 29,2 × 23,6 cm The Museum of Modern Art, New York © 2016. Digital Image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence © Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE Angelus novus, 1920 Oil and watercolour on paper on card 31,8 x 24,2 cm The Israel Museum, Jérusalem © Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE Landschaft bei E. (in Bayern) Paysage près de E. (en Bavière), 1921 Oil and pen on paper on card 49,8 x 35,2 cm © Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE Bild aus dem Boudoir Image tirée du boudoir, 1922 Copy in oil and watercolour on paper on card 33,2 x 49 cm Zentrum Paul Klee, Berne © Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE (Jugendlicher) Schauspieler=Maske [Masque de (jeune)=comédien], 1924 Oil on canvas on card nailed to wood 36,7 x 33,8 cm © Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE von der Liste gestrichen Rayé de la liste, 1933 Oil on paper on card 31.5 x 24 cm

Zentrum Paul Klee, Berne Donation Livia Klee © Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE Der Schöpfer Le Créateur, 1934 Oil on canvas 42 x 53.5 cm Zentrum Paul Klee, Berne © Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE Dame Daemon Dame Démon, 1935 Oil and watercolour on prepared hessian canvas on card 150 x 100 cm Zentrum Paul Klee, Berne © Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE Tänze vor Angst Danses sous l’empire de la peur, 1938 Watercolour on paper on card 48 x 31 cm Zentrum Paul Klee, Berne © Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE Insula dulcamara, 1938 Oil and colour glue paint on paper on hessian canvas 88 x 176 cm Zentrum Paul Klee, Berne© Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE Liebeslied bei Neumond Chant d’amour à la nouvelle lune,1939 Watercolour on hessian canvas 100 x 70 cm Zentrum Paul Klee, Berne © Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE La Belle jardinière, 1939 Oil and tempera on hessian canvas 95 x 71 cm Zentrum Paul Klee, Berne © Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE Übermut Exubérance, 1939 Oil and colour glue paint on paper on hessian canvas 101 x 130 cm Zentrum Paul Klee, Berne © Adagp, Paris 2016

PAUL KLEE Angstausbruch III Explosion de peur III, 1939 Watercolour on prepared paper on card 63.5 x 48.1 cm Zentrum Paul Klee, Berne © Adagp, Paris 2016

,_1901.png)

.jpg!Large.jpg)