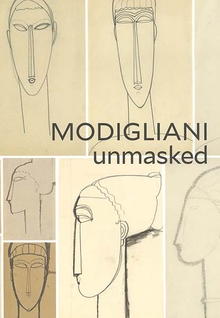

Jewish Museum

September 15, 2017–February 4, 2018

The Jewish Museum presents Modigliani Unmasked,

the first exhibition in the United States to focus on Amedeo

Modigliani’s early work made in the years after he arrived in Paris in

1906. The exhibition puts a spotlight on Modigliani’s drawings, with a

large selection acquired directly from the artist by Dr. Paul Alexandre,

his close friend and first patron. The drawings from the Alexandre

collection, many being shown for the first time in the United States, as

well as other drawings from collections around the world and a

selection of Modigliani’s paintings and sculptures, illuminate how the

artist’s heritage as an Italian Sephardic Jew is pivotal to

understanding his artistic output. The exhibition is on view at the

Jewish Museum from September 15, 2017 through February 4, 2018.

Modigliani Unmasked considers the celebrated artist, Amedeo Modigliani (Italian, 1884-1920), shortly after he arrived in Paris in 1906, when the city was still roiling with anti-Semitism after the long-running tumult of the Dreyfus Affair and the influx of foreign emigres. An Italian Sephardic Jew with a French mother and a classical education, Modigliani was the embodiment of cultural heterogeneity. When he moved to Paris, he came up against the idea of racial purity in French culture — in Italy, he did not feel ostracized for being Jewish. His Latin looks and fluency in French could have easily helped him to assimilate. Instead, his outsider status often compelled him to introduce himself with the words, “My name is Modigliani. I am Jewish.” As a form of protest, he refused to assimilate, declaring himself as “other.” The exhibition shows that Modigliani’s art cannot be fully understood without acknowledging the ways the artist responded to the social realities that he confronted in the unprecedented artistic melting pot of Paris.

In these years prior to World War I, Modigliani largely stopped painting in order to develop his conceptual and pictorial ideas through drawing and sculpture. The works in the exhibition reveal the emerging artist himself, enmeshed in his own particular identity quandary, struggling to discover what portraiture might mean in a modern world of racial complexity.

Modigliani Unmasked is arranged thematically, and includes approximately 130 drawings, 12 paintings, and seven sculptures by the artist. Modigliani’s art is complemented by work representative of the various multicultural influences — African, Asian, Greek, Egyptian, and Khmer — that inspired the young artist during this lesser-known, early period.

When he arrived in Paris, Modigliani — still virtually unknown — met Dr. Alexandre, a young physician. Alexandre amassed some 450 drawings directly from the artist and commissioned a number of portraits. The exhibition includes a selection of drawings depicting Dr. Alexandre, as well as a mysterious, unfinished portrait never seen before in the United States. Probably painted around 1913, it is a stylistic anomaly within Modigliani’s oeuvre, more sketchy and gestural than his typical portraits.

Modigliani would visit museums in Paris, including the Louvre and the Musée du Trocadéro, and was mesmerized by the nonwestern art. Unlike most of his contemporaries in the French vanguard, who appropriated such works expressionistically as an abstracted distortion of the human form, Modigliani’s manner of using such stylized effects was far more respectful. The influence of masks in particular is clearly visible in the many drawings and sculptures in the exhibition.

Prominent in the Alexandre collection are the stylized drawings related to sculptures. Produced between 1909 and 1914, this body of work constitutes a distinct category within the artist’s oeuvre and reveals his ongoing preoccupation with identity. Particularly noticeable is his obsessive examination of physiognomy. When seen together, his repeated images of heads and faces reveal minute, calculated variations in the eyes, noses, and mouths. As seen in the exhibition, this group of drawings offer a nuanced commentary on the underlying issue of aesthetics as it relates to race.

In 1911, Modigliani began to explore a motif borrowed from ancient art, the caryatid, and a selection of these drawings is included in the exhibition. While in classical art the caryatid is usually a woman, his are male, female, or of ambiguous gender. He also incorporated elements derived from Egyptian art, as well as ancient South and Southeastern Asian sources such as facial features, postures, and tattoos.

The exhibition also includes a selection of life studies and female nudes. Among these are of the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, whom the artist met in 1910. Her exotic presence inspired Modigliani to introduce her to Egyptian art. The influences he drew from Egyptian art, such as the attenuation of the figure and the angularity of form, can be seen in the drawings he did of her.

Modigliani’s fondness for performance, including theater, street entertainment, and the circus, is reflected in numerous early drawings, often sketched from a blend of life and imagination. The exhibition includes his drawings of the Commedia dell’Arte character, Columbine, as well as circus performers. Many of these works — like others in the exhibition — reveal the acuity of his psychological awareness, which had the effect of transforming simple sketches into portraits.

Modigliani Unmasked is organized by Mason Klein, Senior Curator, The Jewish Museum. The exhibition was designed by Galia Solomonoff and Talene Montgomery of SAS/Solomonoff Architecture Studio.

Catalogue

The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue published by the Jewish Museum and Yale University Press. The book includes an essay by Mason Klein that offers close analysis of Modigliani’s portraits and figure studies in pencil, ink, gouache, and crayon, ultimately arguing that the artist demonstrated a modernist embrace of difference, as well as an understanding of identity as heterogeneous, beyond national or cultural boundaries. The 172-page book also includes an afterword by Richard Nathanson. Featuring 165 color illustrations, the hardcover will be available worldwide.

Amedeo

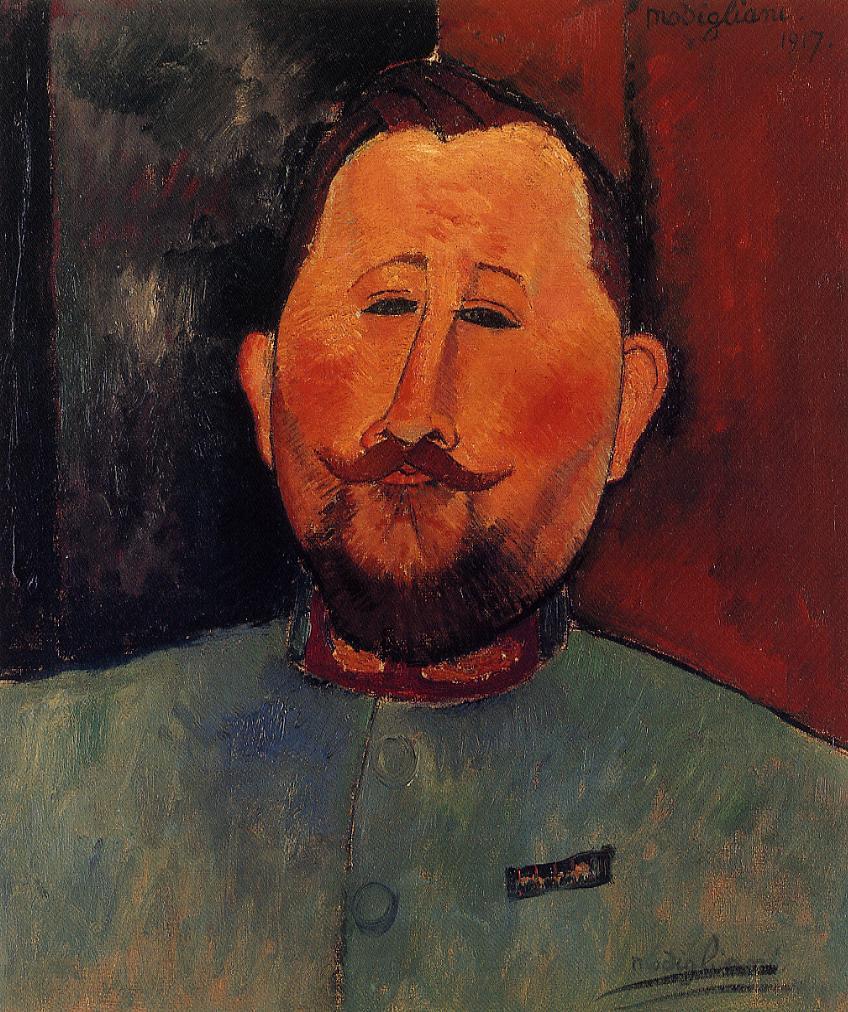

Modigliani Portrait of Docteur Devaraigne, 1917

Oil on canvas

Collection of Bruce and Robbi Toll

Modigliani painted two portraits of Dr. Devaraigne, who was probably a friend. The sitter’s identity is partly established by his military uniform, which suggests that he had been mobilized during World War I. When a subject’s personality or features were particularly striking, as with Dr. Devaraigne, Modigliani would sometimes exaggerate them, increasing the sense of their individuality. Often, especially with people he knew, he painted more than one version of a portrait.

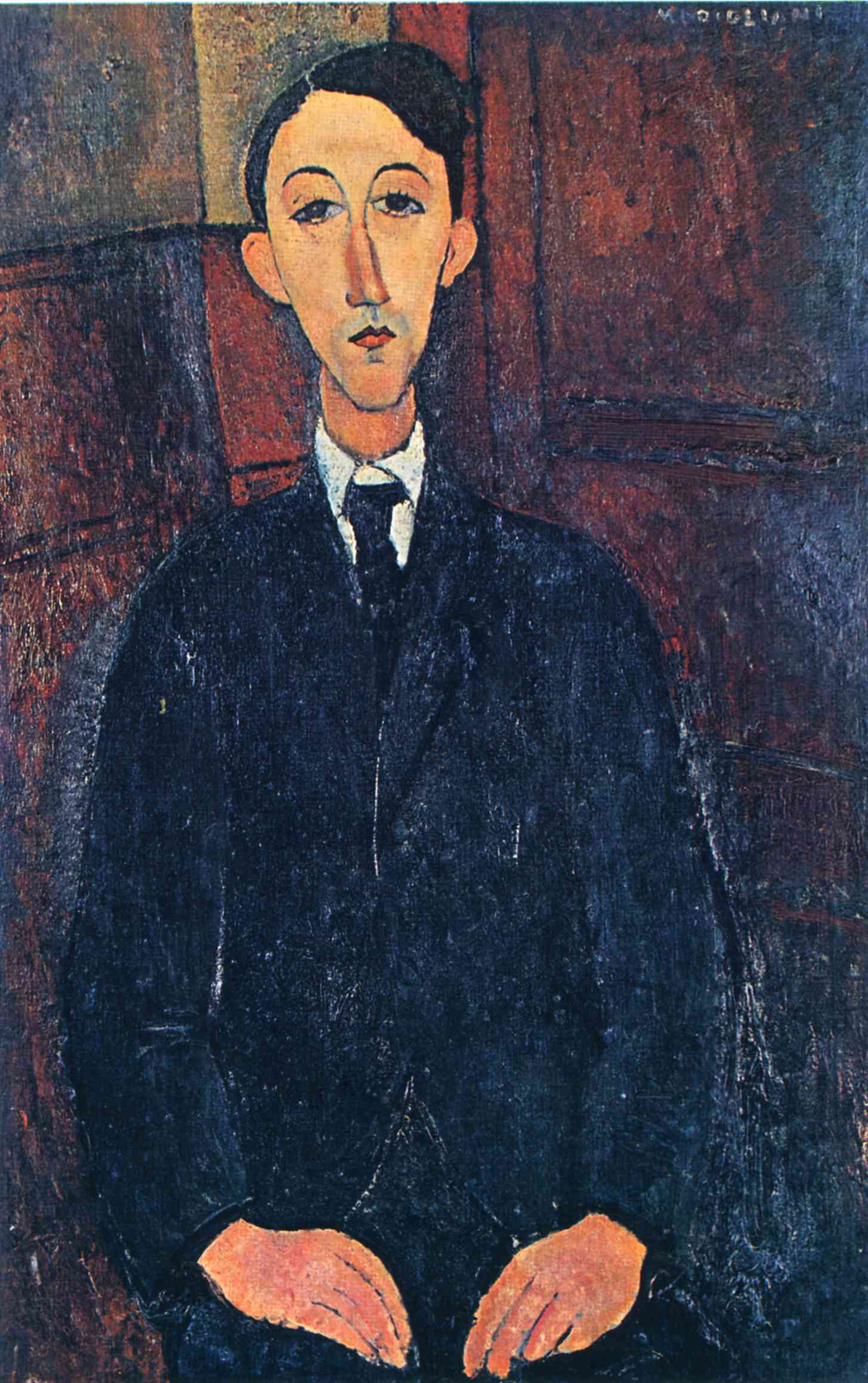

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Manuel Humbert, 1916

Oil on canvas

Collection of Bruce and Robbi Toll

Modigliani immortalized the Spanish landscape painter Manuel Humbert Estève, a struggling artist whom he met in the ethnically diverse environment of Montparnasse. In such paintings, he continued to question portraiture’s claim to truth, presenting the genre as eve rambiguous. Here, he renders the sitter’s head as masklike, with a narrow, triangular face and stylized arched brows connected to a thin, straight nose. But he distinguishes personal features as well —pursed mouth, parted hair —constantly altering the counterpoise of individuality and formal abstraction.

Modigliani Unmasked considers the celebrated artist, Amedeo Modigliani (Italian, 1884-1920), shortly after he arrived in Paris in 1906, when the city was still roiling with anti-Semitism after the long-running tumult of the Dreyfus Affair and the influx of foreign emigres. An Italian Sephardic Jew with a French mother and a classical education, Modigliani was the embodiment of cultural heterogeneity. When he moved to Paris, he came up against the idea of racial purity in French culture — in Italy, he did not feel ostracized for being Jewish. His Latin looks and fluency in French could have easily helped him to assimilate. Instead, his outsider status often compelled him to introduce himself with the words, “My name is Modigliani. I am Jewish.” As a form of protest, he refused to assimilate, declaring himself as “other.” The exhibition shows that Modigliani’s art cannot be fully understood without acknowledging the ways the artist responded to the social realities that he confronted in the unprecedented artistic melting pot of Paris.

In these years prior to World War I, Modigliani largely stopped painting in order to develop his conceptual and pictorial ideas through drawing and sculpture. The works in the exhibition reveal the emerging artist himself, enmeshed in his own particular identity quandary, struggling to discover what portraiture might mean in a modern world of racial complexity.

Modigliani Unmasked is arranged thematically, and includes approximately 130 drawings, 12 paintings, and seven sculptures by the artist. Modigliani’s art is complemented by work representative of the various multicultural influences — African, Asian, Greek, Egyptian, and Khmer — that inspired the young artist during this lesser-known, early period.

When he arrived in Paris, Modigliani — still virtually unknown — met Dr. Alexandre, a young physician. Alexandre amassed some 450 drawings directly from the artist and commissioned a number of portraits. The exhibition includes a selection of drawings depicting Dr. Alexandre, as well as a mysterious, unfinished portrait never seen before in the United States. Probably painted around 1913, it is a stylistic anomaly within Modigliani’s oeuvre, more sketchy and gestural than his typical portraits.

Modigliani would visit museums in Paris, including the Louvre and the Musée du Trocadéro, and was mesmerized by the nonwestern art. Unlike most of his contemporaries in the French vanguard, who appropriated such works expressionistically as an abstracted distortion of the human form, Modigliani’s manner of using such stylized effects was far more respectful. The influence of masks in particular is clearly visible in the many drawings and sculptures in the exhibition.

Prominent in the Alexandre collection are the stylized drawings related to sculptures. Produced between 1909 and 1914, this body of work constitutes a distinct category within the artist’s oeuvre and reveals his ongoing preoccupation with identity. Particularly noticeable is his obsessive examination of physiognomy. When seen together, his repeated images of heads and faces reveal minute, calculated variations in the eyes, noses, and mouths. As seen in the exhibition, this group of drawings offer a nuanced commentary on the underlying issue of aesthetics as it relates to race.

In 1911, Modigliani began to explore a motif borrowed from ancient art, the caryatid, and a selection of these drawings is included in the exhibition. While in classical art the caryatid is usually a woman, his are male, female, or of ambiguous gender. He also incorporated elements derived from Egyptian art, as well as ancient South and Southeastern Asian sources such as facial features, postures, and tattoos.

The exhibition also includes a selection of life studies and female nudes. Among these are of the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova, whom the artist met in 1910. Her exotic presence inspired Modigliani to introduce her to Egyptian art. The influences he drew from Egyptian art, such as the attenuation of the figure and the angularity of form, can be seen in the drawings he did of her.

Modigliani’s fondness for performance, including theater, street entertainment, and the circus, is reflected in numerous early drawings, often sketched from a blend of life and imagination. The exhibition includes his drawings of the Commedia dell’Arte character, Columbine, as well as circus performers. Many of these works — like others in the exhibition — reveal the acuity of his psychological awareness, which had the effect of transforming simple sketches into portraits.

Modigliani Unmasked is organized by Mason Klein, Senior Curator, The Jewish Museum. The exhibition was designed by Galia Solomonoff and Talene Montgomery of SAS/Solomonoff Architecture Studio.

Catalogue

The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue published by the Jewish Museum and Yale University Press. The book includes an essay by Mason Klein that offers close analysis of Modigliani’s portraits and figure studies in pencil, ink, gouache, and crayon, ultimately arguing that the artist demonstrated a modernist embrace of difference, as well as an understanding of identity as heterogeneous, beyond national or cultural boundaries. The 172-page book also includes an afterword by Richard Nathanson. Featuring 165 color illustrations, the hardcover will be available worldwide.

Amedeo Modigliani

Unfinished

Portrait of Paul Alexandre, 1913

Oil on canvas, 31½ x 25¾ in. (80 x 65.6 cm)

Private collection on long-term loan to the Musée des Beaux-Arts,

Rouen

Amedeo Modigliani

The Jewess, 1908

Oil on canvas

21⅝ x 18⅛ in. (54.9 × 46 cm)

Laure Denier Collection, Paul Alexandre Family, courtesy of

Richard Nathanson, London

Amedeo Modigliani

Nude

with a Hat, 1908

Oil on canvas, 31⅞ x 21¼ in. (81 × 54

cm)

Reuben and Edith Hecht Museum,

University of Haifa, Israel

Photo courtesy of the

Hecht Museum, University of Haifa, Israel

Amedeo Modigliani

Jeanne Hébuterne with Yellow Sweater, 1918-19

Oil on canvas

39⅜ x 25½ in. (100 x 64.7 cm)

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, By gift 37.533

Image provided by Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation / Art

Resource, New York

Toward the end of

World War I, Modigliani left Paris for the south of France. In this more serene

environment the artist’s work became more contemplative, his figures

abbreviated and calm, and his palette brighter. Hébuterne, an art student whom

he met at the Académie Colarossi in Paris in the winter of 1916 –17, was his

lover, later his wife. Here he depicts her with affection and no sense of the

erotic. The face is outlined as a long oval, the eyes are blank, and the nose

is long and geometric. The artist underscores the simple elegance of

Hébuterne’s features, rendered as a series of flat shapes —the tilt of her

head, the echoing refrain of the turtleneck sweater and her crossed hands,

while conveying her youthful, moody personality.

Amedeo Modigliani

Lola de Valence, 1915

Oil on paper, mounted on wood, 20½ x 13¼ in. (52.1 x 33.7

cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 67.187.84

Image provided by The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art

Resource, New York

Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot

(1876 – 1967), 1967

This portrait depicts the famous nineteenth -century

Spanish dancer Lola de Valence, also memorialized by the poet Charles

Baudelaire and the painter Édouard Manet. Modigliani’s radical approach to

portraiture is on display here: the dancer’s face is essentially an African

mask.

Amedeo

Modigliani

Lunia Czechowska, 1919

Oil on

canvas, 31½ x 20½ in. (80 x 52 cm)

Museu de

Arte de São Paulo

Assis Chateaubriand, Gift, Raul Crespi, 1952

Photograph by João Musa

Modigliani saw himself

primarily as a sculptor. Even when declining health forced him to abandon the

medium, he continued to think, draw, and paint as one. Lunia Czechowska, a good

friend of Leopold and Hanka Zborowski, became acquainted with the artist an d

emerged as one of his favorite models. Here, Modigliani suppresses descriptive

identity in the service of a universalized presence: he graphically captures

Czechowska’s aristocratic bearing, depicting her like an icon. Her smooth,

ethereal features and exaggeratedly long neck emphasize the image’s sculptural

quality.

Amedeo

Modigliani

Caryatid, c. 1911

Oil on

canvas

28½ x 19¾

in. (72.5 x 50 cm)

Kunstsammlung

Nordrhein-Westfalen, Dusseldorf

Image

provided by bpk Bildagentur / Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen / Art Resource,

NY

Oil on canvas

Collection of Bruce and Robbi Toll

Modigliani painted two portraits of Dr. Devaraigne, who was probably a friend. The sitter’s identity is partly established by his military uniform, which suggests that he had been mobilized during World War I. When a subject’s personality or features were particularly striking, as with Dr. Devaraigne, Modigliani would sometimes exaggerate them, increasing the sense of their individuality. Often, especially with people he knew, he painted more than one version of a portrait.

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Manuel Humbert, 1916

Oil on canvas

Collection of Bruce and Robbi Toll

Modigliani immortalized the Spanish landscape painter Manuel Humbert Estève, a struggling artist whom he met in the ethnically diverse environment of Montparnasse. In such paintings, he continued to question portraiture’s claim to truth, presenting the genre as eve rambiguous. Here, he renders the sitter’s head as masklike, with a narrow, triangular face and stylized arched brows connected to a thin, straight nose. But he distinguishes personal features as well —pursed mouth, parted hair —constantly altering the counterpoise of individuality and formal abstraction.

Amedeo ModiglianiHanka Zborowska, 1916

Oil on canvas

Private collection

Based on stylistic similarities with other paintings of 1916, this work is quite likely the first of a series of twelve portraits of the common-law wife of the poet Leopold Zborowski, who was Modigliani’s art dealer during the last years of his life. Here, the artist balances the generic artifice of the mask with the particular self absorption of the sitter, a tension that resonates in his metaphoric use of an inner and outer eye.

Amedeo Modigliani

Portrait of Roger Dutilleul. 1919

Oil on canvas

Collection of Bruce and Robbi Toll

This classic example of Modigliani’s consummate painterly style pays homage to one of his most devoted patrons, Roger Dutilleul. Unable to afford to collect the work of more established figures, Dutilleul turned to young contemporary artists. Between 1918 and 1925 he acquired thirty -four paintings and twenty -one drawings, virtually ten percent of Modigliani’s late work.

Jacques Lipchitz

Death Mask of Amedeo Modigliani, 1920,

Cast plaster

The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago,

Bequest of Joseph Halle Schaffner in memory of his beloved mother, Sara H. Schaffner

Modigliani succumbed to tubercular meningitis on Saturday evening, January 24, 1920, at the Hôpital de la Charité on Paris’s left bank. Two of his fellow artists, Moïse Kisling and Conrad Moricand, attem pted to make a death mask before his burial in Père Lachaise Cemetery. Neither painter possessed the necessary technical skills; they removed the plaster mold too early, and broke it. The sculptor Jacques Lipchitz, another Jewish artist resident in Paris and a close friend of Modigliani, salvaged the mask; he produced a number of plaster casts and, eventually, an edition in bronze.