SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT,

OCTOBER 27, 2017 – FEBRUARY 25, 2018

Social tensions, political struggles, social upheavals, as well as artistic revolutions and innovations characterize the Weimar Republic. Beginning October 27, 2017, the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt is presenting German art from 1918 to 1933 in a major thematic exhibition.

Direct, ironic, angry, accusatory, and often even prophetic works demonstrate the struggle for democracy and paint a picture of a society in the midst of crisis and transition. Many artists were moved by the problems of the age to mirror reality and everyday life in their search for a new realism or “naturalism.” They captured the stories of their contemporaries with an individual signature: the processing of the First World War with depictions of maimed soldiers and “war profiteers,” public figures, the big city with its entertainment industry and increasing prostitution, political unrest and economic chasms, as well as the role model of the New Woman, the debates about paragraphs 175 and 218 (regarding punishability of homosexuality and abortion), the social changes resulting from industrialization, and the growing enthusiasm for sports.

The exhibition provides an impressive panorama of a period that even today, 100 years after its advent, has lost nothing of its relevance and potential for discussion. The focus of the exhibition lies on the unease of the era , which was reflected not only in the motifs and content, but also in a broad spectrum of styles. Arranged in thematic groups, it assembles portrayals and scenes from Berlin, Dresden, Leipzig, Rostock, Stuttgart, Karlsruhe, Munich, and Hannover that have hitherto frequently been regarded separately and can be assigned more to the “verist” wing of New Objectivity .

The exhibition assembles 190 paintings, prints, drawings, and sculptures by 62 famous artists and others who have been largely neglected to date, including Max Beckmann, Kate Diehn - Bitt, Otto Dix, Dodo, Conrad Felixmüller, George Grosz, Carl Grossberg, Hans an d Lea Grundig, Karl Hubbuch, Lotte Laserstein, Alice Lex - Nerlinger, Elfriede Lohse - Wächtler, Jeanne Mammen, Oskar Nerlinger, Franz Radziwill, Christian Schad, Rudolf Schlichter, Georg Scholz, and Richard Ziegler. Historical films, magazines, posters, and p hotographs provide add itional background information.

The Schirn was able to arrange important loans from numerous museums as well as public and private collections in Germany and abroad for this presentation, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and t he Neue Galerie in New York, the Museo Thyssen - Bornemisza Madrid, the Museum Moderne Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien, the Nationalgalerie of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, the Albertinum of the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, the Städtische Galerie im Len bachhaus Munich, the Sprengel Museum Hannover, the Kunstmuseum Stuttgart, the Folkwang Museum Essen, and the Stiftung Museum Kunstpalast Düsseldorf.

Dr. Philipp Demandt, Director of the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt, remarks about the exhibition:

“ With ‘Splendor and Misery in the Weimar Republic’ the Schirn is presenting a counterbalance to the exhibitions that have already be en shown on many occasions on the Roaring Twenties. It takes a look at the unvarnished facts of life during the Weimar Republic. 190 works by 62 artists mercilessly hold a mirror to the society of the time. We see an era that clung to democracy by the skin of its teeth and in some respects is closer to u s than we would like to believe. ”

The curator of the exhibition, Dr. Ingrid Pfeiffer, explains :

“ We often read the history of the Weimar Republic from the end backwards — from its transition to National Socialism and World War II. In spite of the negative sociopolitical developments that the artists so succinctly describe in their works, it was during the Weimar Republic that ‘modernism ’ evolved. The Weimar Republic was a progressive era in which many pioneering ideas were formed — not only in art, architecture, and design. The direction in which the Republic should develop was energetically discussed on all levels, the role of women, the length of the working week , and the paragra phs relating to abortion and homosexuality. Besides the manifest misery, it is these tendencies that for me distinguish th e splendor of the Weimar Republic . ”

THE THEMES AND ARTISTS OF THE EXHIBITION

One of the first works in the presentation is the painting Weimarer Fasching ( Weimar Carnival , ca. 1928/ 29) by Horst Naumann ( 1908 – 1990) — a p anorama of society, a c on c entr ated overview of those phe nomen a that defined the Weimar Republic : the entertainment industry, money, sports , the church, the army, weapons, right - wing national ist s ymboli sm , and industrial progress . T he economic consequences of the war and the moral burden resulting from the Treaty of Versailles and its article relating to the blame for the war weighed heavily on the Weimar Republic and posed a massive threat to the young democracy. In the years following World War I, in their works artists Otto Dix (1891 – 1969) , Georg e Grosz ( 1893 – 1959), and Georg Scholz ( 1890 – 1945 ) in particular rea cted to the political and economic conditions within the Republic with scathing criticism . War invalids, day laborers , and the unemployed were a frequent sight and also appeared as subjects in art.

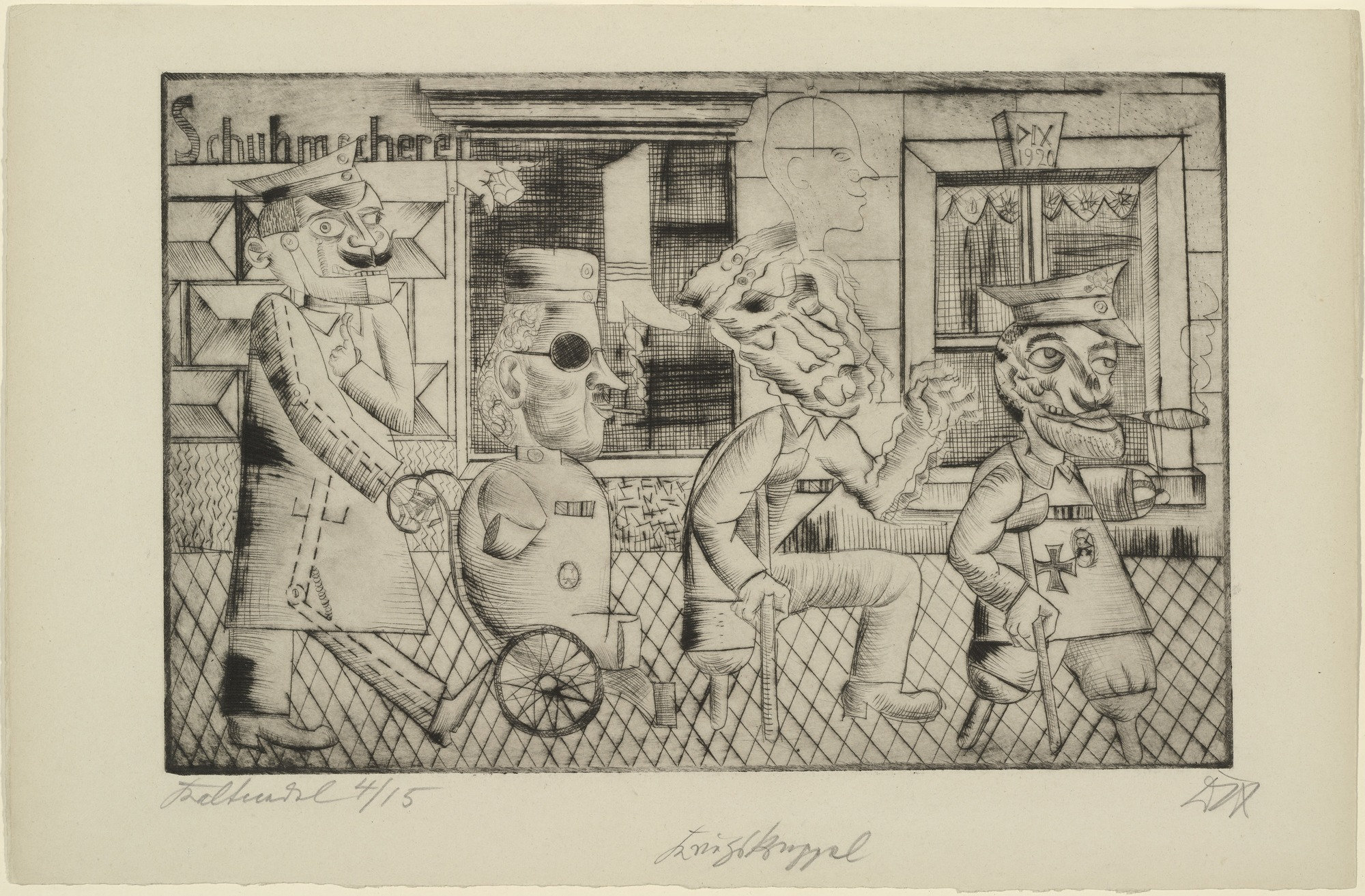

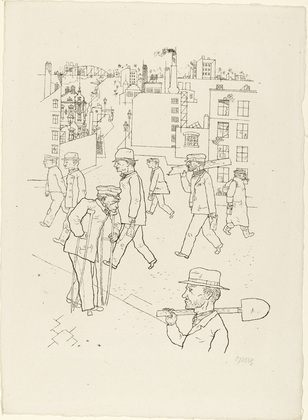

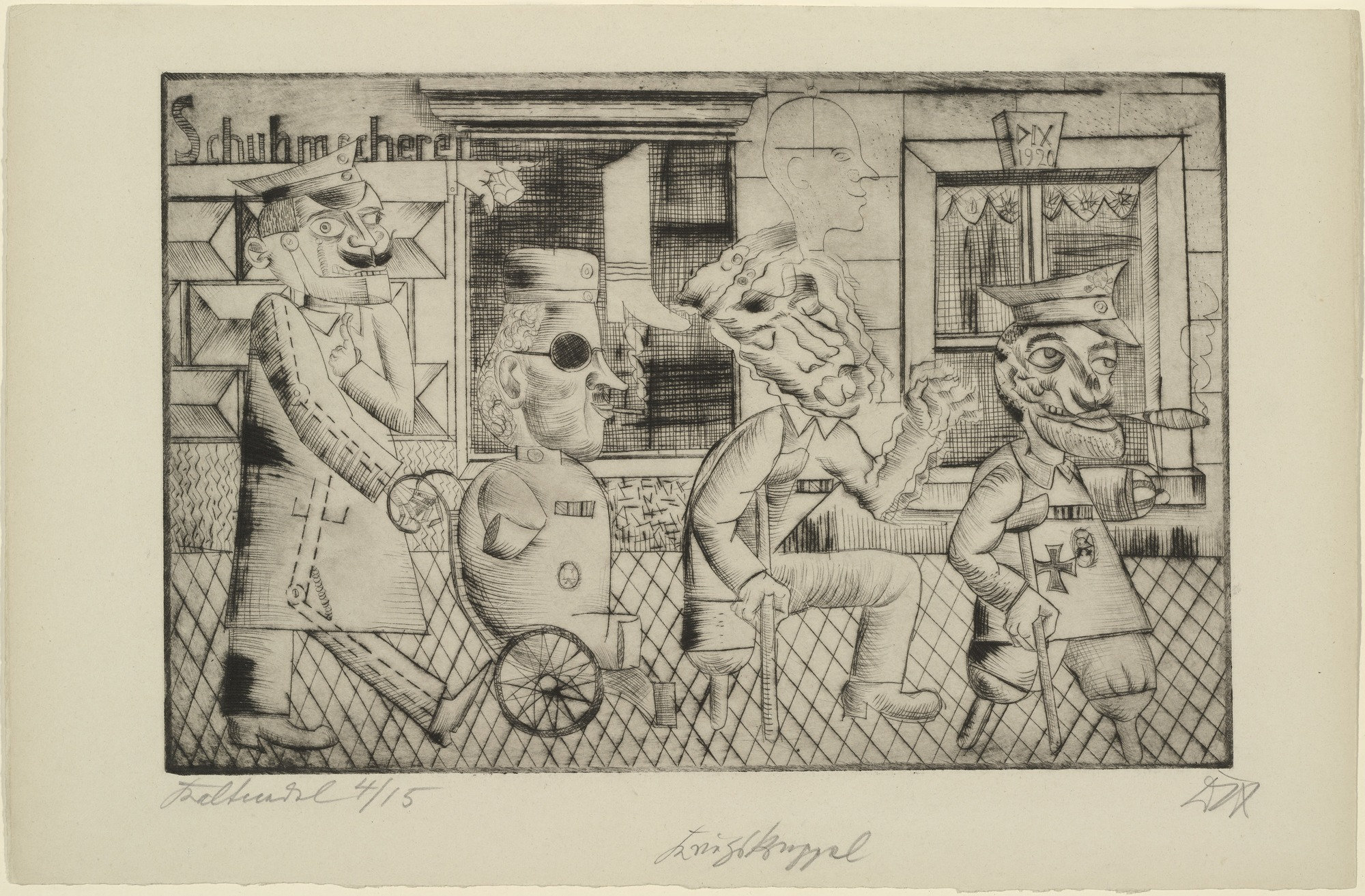

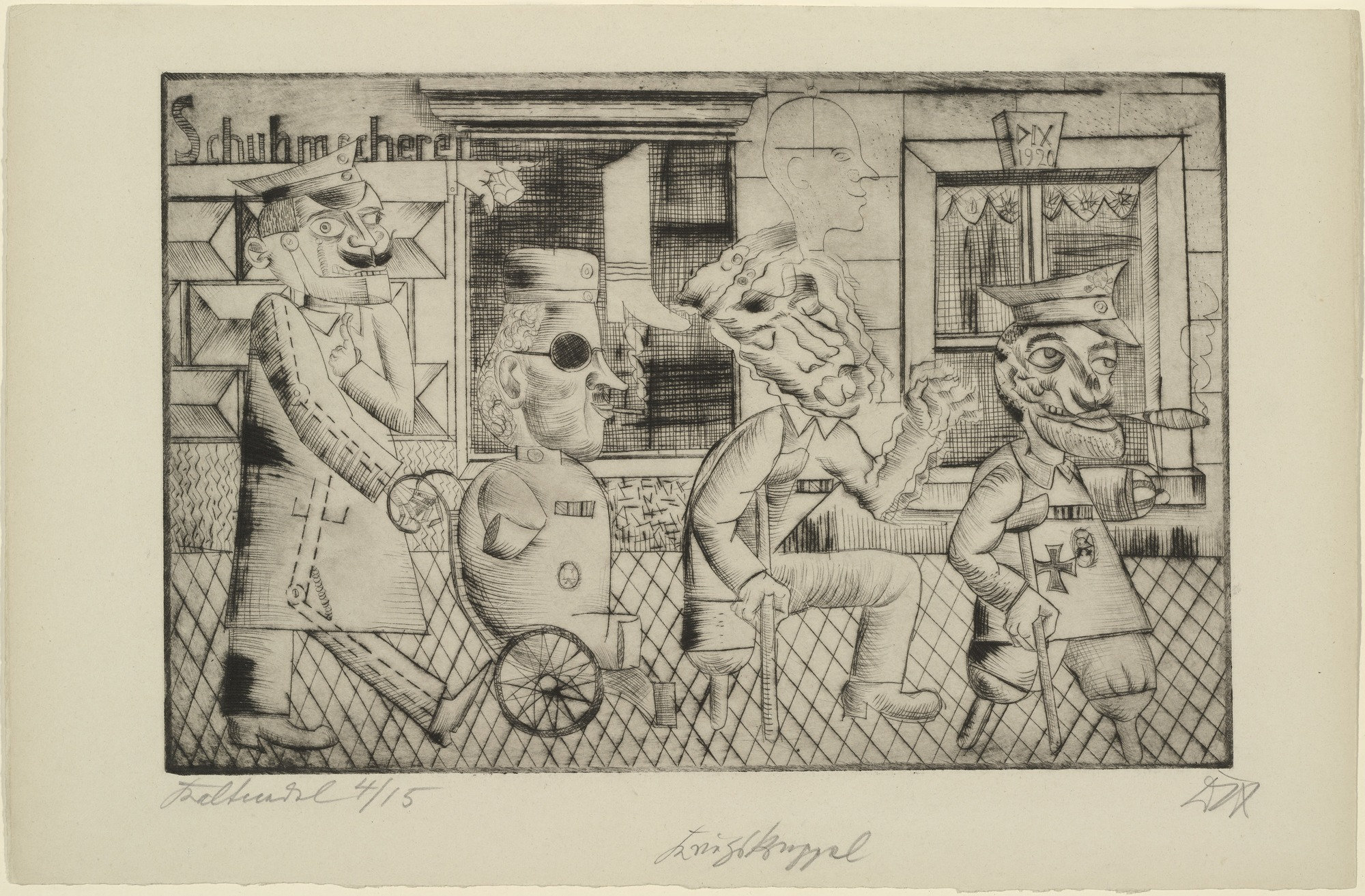

The Schirn shows works like Otto Dix ’s Kriegskrüppel (War Cripples, 1920)

and George Grosz's Invalide ( Invalid, 1921/22), which depict the situation in the streets directly and with mordant humor. With their highly political art, George Grosz and Georg Scholz also took a stance against National Socialist tendencies and in retrospect demonstrate an almost prophetic foresight with regard to future events.

Georg Scholz, for example, painted his so - called Hakenkreuzritter (Swastika Knight ) in a café as early as 1921.

Since the founding of the Weimar Republic, opponents on the right and left fought against it, since they both wanted a very different kind of social and political order in Germany. Communist revolts and extreme right - wing attempts at a coup d’état were both real and hypothetical dangers. As early as 1922, Otto Griebel (1895 – 1972) was one of the first artists to portray the political and social contrasts that the young republic had to face .

Along with Lea Grundig (1906 – 1977) and Hans Grundig (1901 – 1958) , Conrad Felixmüller (1897– 1977) , Alice Lex - Nerlinger (1893 – 1975) , Curt Querner ( 1904 –1976 ) , and Otto Nagel (1894 – 1967) , Otto Griebel was also a member of the Assoziation Revolutionärer Bildender Künstler Deutschlands (Association of Revolutionary Artists of Germany, ASSO or ARBKD), which was founded first in Berlin and then in 1 930 in Dresden and through which the artists took an active part in political events .

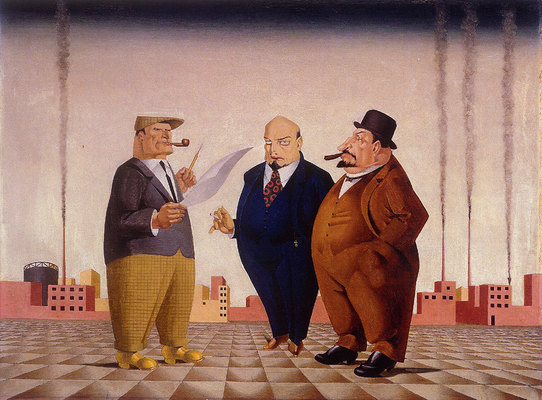

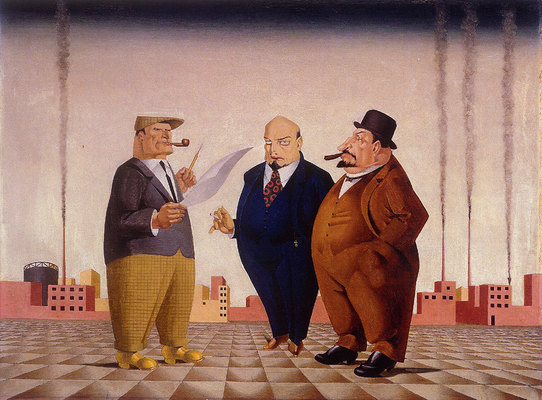

Georg Scholz made the growing social injustice in the Weimar Republic a subject of his work, for example in his painting Von kommenden Dingen (Of Things to Come, 1922), in which he illustrated a questionable deal between the most important string - pullers of the early Weimar Republic: the industrialist Hugo Stinnes, the politician Walther Rathenau , and the trade - union leader Carl Legien.

The petit - bourgeois and the well - fed citizen, the industrialist who profited from inflation, and the nouveau - riche individual all cropped up in pict u res of the time, as in Der Schieber ( The Trafficker, 1921/22) by Heinrich Maria Davringhausen ( 1894 – 1970) . These are contrasted by portraits such as Arbeitslose (Unemployed Workers , 1929) o r Stoffhändler (Fabric Merchant , 1932) by Grethe Jürgens ( 1899 – 1981) , in which the artist depicted the harsh and immediate present .

In the Weimar Republic cultural events were no longer merely the privilege of an élite but became mass entertainment : varietés, revue theater, nightclub , cafés, and bars were features of social life in the big cities and offered opportunities to escape from everyday life.

The Schirn has assembled images such as

Tiller Girls ( before 1927) by Karl Hofer (1878 – 1955) ,

Varieté (1925) by Paul Grunwaldt (1891 – 1962 ) ,

and Lissy im Café ( Lissy in the Café , ca. 1930/ 32) by Karl Hubbuch (1891 – 1979).

The illustrations and drawings for the satirical magazines Ulk Simplicissimus, and Jugend,

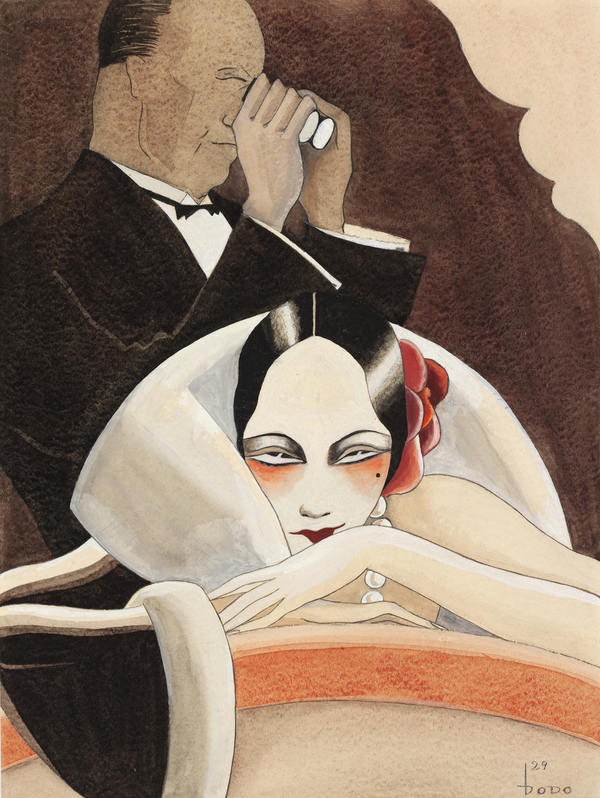

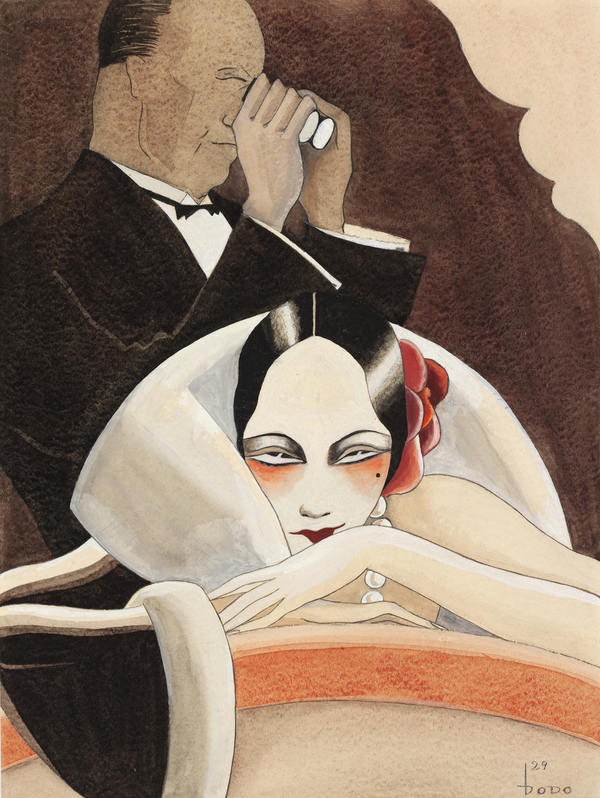

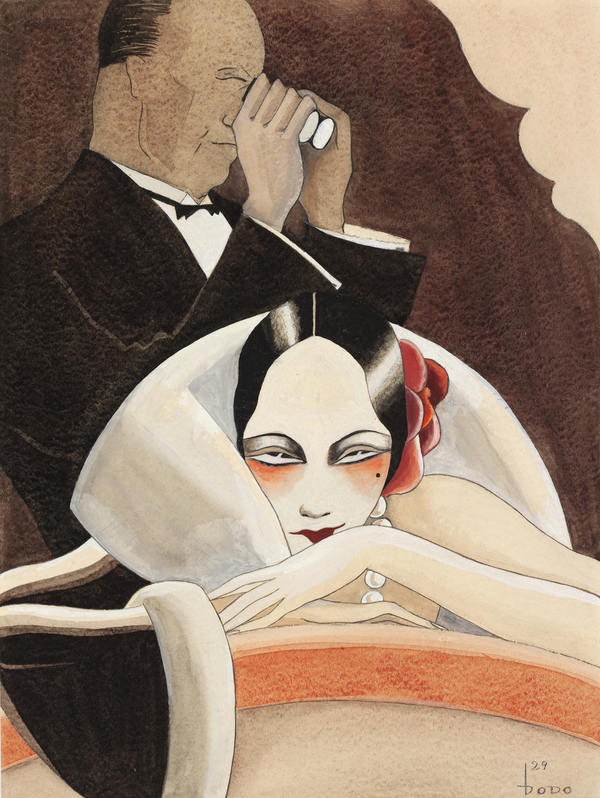

Dodo, Box Logic (Logenlogik), for the magazine Ulk, 1929, Gouache over pencil on cardboard, 40 × 30 cm, Private collection, Hamburg, © Krümmer Fine Art

including Logenlogik (Box Logic , 1929) by Dodo ( 1907 – 1998 ) or

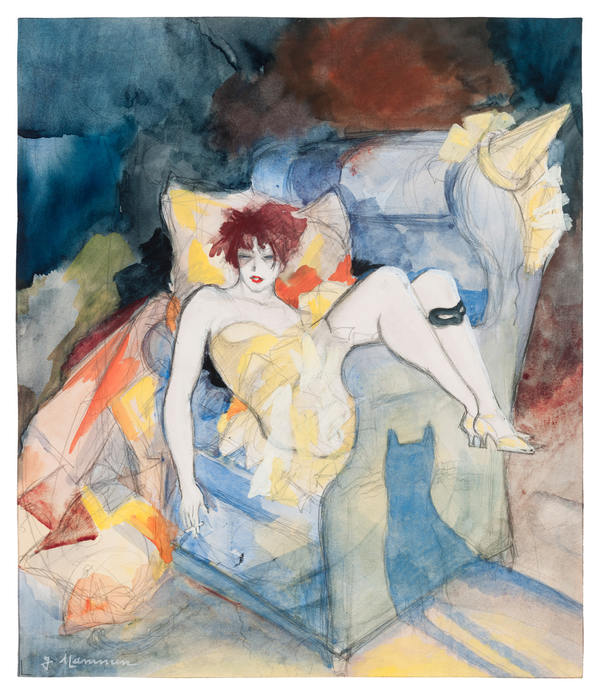

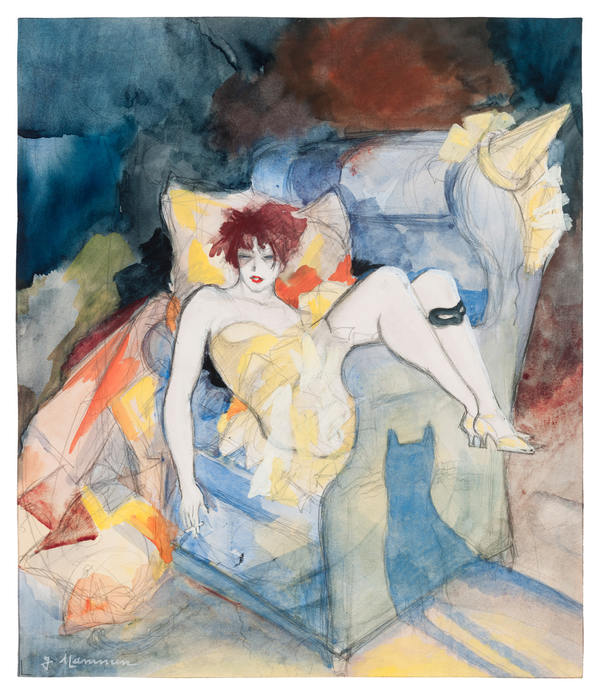

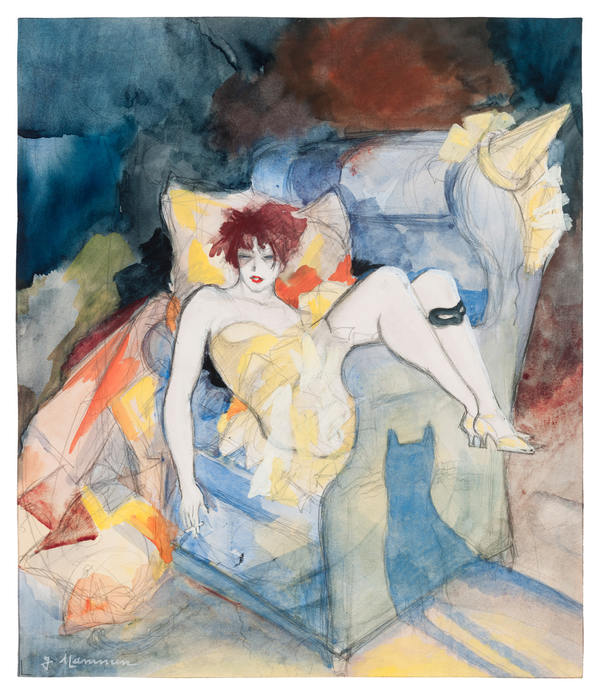

Jeanne Mammen, Ash Wednesday (Aschermittwoch), ca. 1926, Watercolor on paper, 34 × 29 cm, Private collection, Berlin, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, Photo: Mathias Schormann, Berlin

Aschermittwoch ( Ash Wednesday , ca. 1926) by Jeanne Mammen ( 1890 – 1976) , bear witness to a dissolute, heedless drive and show the abysses and dark sides of the world of entertainment .

Increasing prostitution was portrayed not only in a sociocritical manner

by Heinrich Ilgenfritz (1899 – 1969) , for example in Die Ernährerin (The Breadwinner , 1928 – 1932), or grotesquely by George Grosz or

Otto Dix in Dame mit Schleier und Nerz ( Woman with Mink and Veil , 1920) , but also more subtly and with more empathy, for example inOtto Dix, Woman with Mink and Veil (Dame mit Schleier und Nerz), 1920, Oil and tempera on canvas mounted on board, 73 × 54.6 cm, Judy and Michael Steinhardt Collection, New York, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017

Rudolf Schlichter, Margot, 1924, Oil on canvas, 110.5 × 75 cm, Stadtmuseum Berlin, © Viola Roehr von Alvensleben, München, Photo: Michael Setzpfandt, Berlin

Margot (1924) by Rudolf Schlichter ( 890 – 1955) or in the works of Elfriede Lohse - Wächtler (1899– 1940) . The latter lived for a time in Sankt Pauli in Hamburg: her pictures are drastic, as in Über der Leib (About the Body, 1930), but often also almost humorous and full of sympathy.

The role model of women changed fundamentally during the Weimar Republic . Correspondingly, artists such as Lotte Laserstein ( 1898 – 1993) and Kate Diehn - Bitt ( 1898 – 1993) portrayed themselves corresponding to the image of the New Woman as urban and self-confident with a bob and at times androgynous. Large numbers of women now took up new professions and became telephone operators, saleswomen, doctors, or academics .

Almost one - third of the artists whose works are being presented in the Schirn exhibition are female — artists who were hitherto often missing from overview publications on New Objectivity. Their works also reflect the social developments in the direction of more liberality and pluralism.

The “Women’s Question” also influenced political debates on abortion (Paragraph 218) and contraception, marital rights, prostitution , women’s wages , and even cultural - critical debates on fashion and sexual orientation.

Women artists developed their own versions and forms of social realism not only in Berlin, with Jeanne Mammen, Lotte Laserstein, and Alice Lex - Nerlinger, but also in many other places — Gerta Overbeck (1898 – 1977 ) and Grethe Jürgens in Hannover, Lea Grundig a nd Hilde Rakebrand ( 1901 – 1991 ) in Dresden, Kate Diehn - Bitt in Rostock, Elfriede Lohse - Wächtler in Hamburg, and Hanna Nagel (1907 – 1975 ) in Karlsruhe.

The exhibition presents important personalities of public life during the Weimar Republic , including gallerists, journalists, writers, and composers, as well as industrialists, doctors, and scientists . The portraits by New Objectivity artists such as Erich Büttner ( 1889 – 1936), Kurt Lohse ( 1892 – 1958), and Christian Schad (1894 – 1982) are not only depictions of character, but powerful commentaries as well.

In addition to these real personalities, who can also be seen as representatives of professions and functions, typological portraits were also produced, such as

Kurt Günther, The Radioist (Citizen on the Radio) (Der Radionist [Kleinbürger am Radio]), 1927, Tempera on wood, 55 × 49 cm, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie, Photo: bpk / Nationalgalerie, SMB / Klaus Göken, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Der Radionist (Kleinbürger am Radio) ( The Radionist [Citizen on the Radio] , 1927) by Kurt Günther ( 1893 – 1955) .

As a new medium, the radio was both a leisure pursuit and a source of information . The show also takes up another topic of the time: sports . For workers, the middle classes, and intellectuals, sporting contests embodied a new attitude to ward life.

The Schirn presents, for instance

Rugbyspieler (Rugby Players , 1929) by Max Beckmann (1884 – 1950),

Der Schaubudenboxer (The Booth Boxer , 1921) by Conrad Felixmüller,

sculptures by Renée Sintenis (1888 – 1965) depicting sports such as running, soccer, and boxing, and excerpts from the documentary film Wegezu Kraft und Schönheit ( Ways to Health and Beauty , 1925).

One of the most frequent artistic subjects of the time is industrialization, with representations o f machines, factories, train stations, and bridges. The industrial sites are for the most part not shown as being filled with bustling activity, but rather as cool and uninhabited. The increasing skepticism toward the optimism about progress and enthusiasm for technology manifests in these melancholy , seemingly apocalyptic landscapes or, for example in the large - format and full - canvas machines by Carl Grossberg ( 1894 – 1940) .

The Weimar Republic can be regarded as a

period of transition from the German Empire to the dictatorship of National Socialism : tension, an ominous feeling, the premonition of an imminent c atastrophe

is visible in many images of the time. The disquiet of the age is subliminally

clear, as in the painting

Todessturz Karl Buchstätters ( Karl Buchstätter Falls to his Death , 1928) by Franz Radziwill ( 1895 – 1983) . His biography, like that of Rudolf Schlichter mirrors the vacillation between political convictions and the ambiguous relationship to National Socialism that was characteristic of the time .

CATALOG

Glanz und Elend in der Weimarer Republik / Splendor and Misery in the Weimar Republic, edited by Ingrid Pfeiffer, with a foreword by Philipp Demandt, essays by Andreas Braune, Karoline Hille, Annelie Lütgens, Stéphanie Moeller, Olaf Peters, Dorothy Price, as well as Marti na Wein land and Ingrid Pfeiffer, and including artists’ biographies and a chronology of the Weimar Republic. German and English editions, each ca. 300 pages, ca. 260 illustrations, 29 x 24 cm, hardcover; graphic design: Sabine Frohmader; Hirmer Verlag, Munich, IS BN 978 - 3 - 7774 - 2932 - 8 (German), ISBN 978 - 3 - 7774 - 2933 - 5 (English) ,

Todessturz Karl Buchstätters ( Karl Buchstätter Falls to his Death , 1928) by Franz Radziwill ( 1895 – 1983) . His biography, like that of Rudolf Schlichter mirrors the vacillation between political convictions and the ambiguous relationship to National Socialism that was characteristic of the time .

CATALOG

Glanz und Elend in der Weimarer Republik / Splendor and Misery in the Weimar Republic, edited by Ingrid Pfeiffer, with a foreword by Philipp Demandt, essays by Andreas Braune, Karoline Hille, Annelie Lütgens, Stéphanie Moeller, Olaf Peters, Dorothy Price, as well as Marti na Wein land and Ingrid Pfeiffer, and including artists’ biographies and a chronology of the Weimar Republic. German and English editions, each ca. 300 pages, ca. 260 illustrations, 29 x 24 cm, hardcover; graphic design: Sabine Frohmader; Hirmer Verlag, Munich, IS BN 978 - 3 - 7774 - 2932 - 8 (German), ISBN 978 - 3 - 7774 - 2933 - 5 (English) ,

WALL

PANELS OF THE EXHIBITION

As

the first German democracy and a brief “golden” age at the beginning of the

twentieth century, the Weimar Republic was a key epoch. It is regarded to this

day as the prototype for many of the social and societal achievements which we

take for granted today. At the same time it is also a monume nt to failure,

because from the outset the young democracy was violently resisted by strong

forces. It was both highly vulnerable and shaken by crises. Many artists

reacted to this situation in their works after the First World War with

realism, directness , irony, anger, humor, innuendo, restraint, and melancholy.

The exhibition “ Splendor and Misery in the Weimar Republic ” concentrates on

questions of content and focuses on the political and social tensions of those

years. The exhibition investigates the all - pervad ing inherent “unease of

the age” : many of the artists turned out to be seismographs of the era and

seem to have anticipated the failure of the Weimar Republic long before the

catastrophe actually occurred.

THE NEW OBJECTIVITY – TOPICS AND SUBJECTS

After

the First World War the abstraction and intellectualization of Expressionism

gave way to the desire for a more realistic portrayal of the immediate present,

for a new Naturalism. What came to be known as the “New Objectivity” developed

as a contemporary style which seemed to represent the modern world with

particular clarity: cool, detached, and dispassionate, with sharp outlines and

painted in the style of the old masters, and yet at the same time ambiguous and

full of innuendo.

The exhibition with 190 works by 62 artists concentrates on

the veristic and political wing of New Objectivity. In addition to the splendor

and the social and societal achievements, many artists also focused their

attention on the dar k sides of the period. They wanted to show actively the social

wrongs in order not only to depict their crisis - ridden age but also to

comment on it trenchantly and change it. Lively centers of art arose not only

in Berlin, but also in many cities including Dresden, Rostock, Stuttgart,

Karlsruhe, Munich, Hamburg, and Hannover.

The nine rooms dedicated to different

topics – Politics, the Entertainment Industry, Prostitution, the New Woman,

Paragraphs 218 and 175, Industrial Landscapes, Sport , and Social Topics – create

a wide - ranging panorama of art and society in the Weimar Republic .

IMAGES

Kate

Diehn-Bitt, Self-Portrait with Son (Selbstbildnis mit Sohn), 1933, Oil on

plywood, 99 × 74 cm, Kunsthalle Rostock

Otto

Dix, Woman with Mink and Veil (Dame mit Schleier und Nerz), 1920, Oil and

tempera on canvas mounted on board, 73 × 54.6 cm, Judy and Michael Steinhardt

Collection, New York, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017

Otto

Dix, Pimp and Girl (Zuhälter und Prostituierte), 1923, Brush, India ink and

watercolor on tracing paper, 51.4 × 38.1 cm, The Morgan Library &

Museum, Bequest of Fred Ebb, 2005.126, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, Photo: Janny

Chiu 2015

Dodo,

Box Logic (Logenlogik), for the magazine Ulk, 1929, Gouache over pencil on

cardboard, 40 × 30 cm, Private collection, Hamburg, © Krümmer Fine Art

Carl

Grossberg, White Tanks (Harburg Oil Refinery) (Weiße Tanks [Harburger

Ölwerke]), 1930, Oil on canvas, 90 × 70 cm, Olcese Family Collection, ©

Collection Family Olcese

George

Grosz, Street Scene (Kurfürstendamm) (Straßenszene [Kurfürstendamm]), 1925, Oil

on canvas, 81.3 × 61.3 cm, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, © VG Bild-Kunst,

Bonn 2017

Kurt

Günther, The Radioist (Citizen on the Radio) (Der Radionist [Kleinbürger am

Radio]), 1927, Tempera on wood, 55 × 49 cm, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin,

Nationalgalerie, Photo: bpk / Nationalgalerie, SMB / Klaus Göken, © VG

Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Alice

Lex-Nerlinger, Paragraph 218, 1931, Spray technique, acrylic on canvas, 95 ×

76.5 cm, Stiftung Stadtmuseum Berlin, © Sigrid Nerlinger, Stadtmuseum Berlin,

Photo: Michael Setzpfandt, Berlin

Elfriede

Lohse-Wächtler, The Cigarette Break (Self-Portrait) (Die Zigarettenpause

[Selbstbildnis]), 1931 Watercolor over pencil, 58 × 44 cm Förderkreis Elfriede

LohseWächtler e. V. Hamburg, © Nachlassverwaltung Elfriede

Lohse-Wächtler

Jeanne

Mammen, Ash Wednesday (Aschermittwoch), ca. 1926, Watercolor on paper, 34 × 29

cm, Private collection, Berlin, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, Photo: Mathias

Schormann, Berlin

Horst

Naumann, Weimar Carnival (Weimarer Fasching), ca. 1928/29, Oil on canvas, 91 ×

71 cm, Albertinum/Galerie Neue Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, ©

Estate Naumann, photo: bpk /Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Elke

Estel/Hans-Peter Klut

Max

Oppenheimer, Six-Day Race (Sechstagerennen), ca. 1929, Oil on canvas, 73.5 × 87

cm, Private collection, Fotostudio Bartsch, Karen Bartsch, Berlin

Kurt

Querner, Agitator, 1931, Oil on canvas, 160 × 100 cm, Staatliche Museen zu

Berlin, Nationalgalerie, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, photo: bpk /

Nationalgalerie, SMB / Bernd Kuhnert

Franz

Radziwill, Karl Buchstätter Falls to His Death (Todessturz Karl Buchstätters),

1928, Oil on canvas, 90.4 × 94.5 cm, Museum Folkwang, Essen, © VG Bild-Kunst,

Bonn 2017, Photo: Museum Folkwang Essen - ARTOTHEK

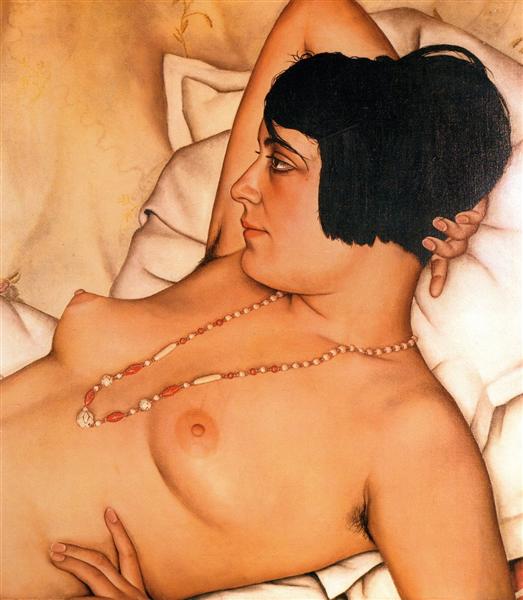

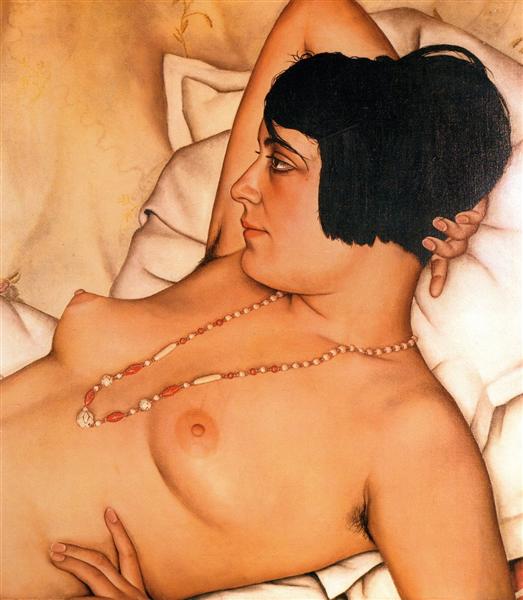

Christian

Schad, Seminude (Halbakt), 1929, Oil on canvas, 55.5 × 53.5 cm, Von der

Heydt-Museum Wuppertal, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, Photo: Antje Zeis-Loi,

Medienzentrum Wuppertal

Christian

Schad, Boys in Love (Liebende Knaben), 1929/72, Lithograph, 30 × 23.5 cm,

Christian-Schad-Stiftung Aschaffenburg, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, Photo: Jens

Oschik, Museen der Stadt Aschaffenburg

Rudolf

Schlichter, Margot, 1924, Oil on canvas, 110.5 × 75 cm, Stadtmuseum Berlin, ©

Viola Roehr von Alvensleben, München, Photo: Michael Setzpfandt, Berlin

Georg

Scholz, Café (Swastika Knight) (Café [Hakenkreuzritter]), 1921, Watercolor, 30

× 49 cm, Merrill C. Berman Collection, New York, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017,

photo: Galerie Michael Hasenclever

Georg

Scholz, Of Things to Come (Von kommenden Dingen), 1922, Oil on cardboard, 74.9

× 96.9 cm, Neue Galerie New York, Photo: bpk / Neue Galerie New York / Art

Resource, NY

ART AND

POLITICS

The trauma of defeat in the First World War was the tremendous burden

which weighed heavily on the Weimar Republic and represented a massive threat t

o the young democracy. The army was to be reduced within a short space of time

to 100,000 soldiers, and this led to enormous political and social problems. In

addition German society had to cope with two million dead and some 1.5 million

war invalids crowding the cities. Although the government had promised them different

treatment, these former soldiers received either a pittance of a pension or no

pension at all, and had to beg on the streets.

In his graphic works Otto Dix portrayed the War Cripples as a horrifying succession of figures maimed by gas and with various body parts amputated, a grotesque procession of outcasts.

Through his

provocative and politically highly topical art, George Grosz in particular was subjected

to hostilities from right - wing nationalist circles. In 1921 he was sentenced

to a fine of 5,000 Marks because he had described the military as “whoremongers

of death”.

His early portraits of Adolf Hitler in the magazine Die Pleite from 1923 show Grosz as an artist who recorded the under currents of tension and political dislocations of his age.

His early portraits of Adolf Hitler in the magazine Die Pleite from 1923 show Grosz as an artist who recorded the under currents of tension and political dislocations of his age.

THE ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY

After the First World War,

in spite of the social chaos, hunger, and inflation a highly stimulating scene

of cabarets, dance clubs, and night spots developed in Berlin in particular.

Here tourists could find “everything” : those from abroad maintained that

Berlin even surpassed Paris with regard to perversions, as Curt Moreck’s Führer

durch das “lasterhafte” Berlin described. Alcohol and cocaine were both

consumed in excessive quantities: the price for a kilogram of cocaine rose from

16 Marks before the war to 17,000 Marks in 1921.

The revues were especially

popular: the open display of virtually naked bodies combined with extravagant

costumes and synchronized choreography was a success formula whose popularity extended

far beyond Berlin. In 1923 there were 360 revues in 119 German cities. During

the years 1926/27 the nine revue theaters in Berlin which put on nightly

performances attracted an estimated 11,000 s pectators.

The most famous

performances were those presented before audiences of 2,000 in the Admiralspalast,

where Hermann Haller produced the English Tiller Girls, whose precisely coordinated

dance line-ups to contemporary American music echoed not only the army but

also the assembly - line work which was becoming more widespread at the time.

Klaus Mann wrote: “ Dance became a mania, an idée fixe , a cult ... it was the

dance of hunger and hysteria, fe ar and greed, panic and horror.”

PROSTITUTION

AS A GROWING SOCIAL PHENOMENON

Between 1913 and 1925 the number of officially

registered prostitutes in German cities like Berlin, Hamburg, Frankfurt, and

Leipzig doubled. If the illegal prostitutes who had been arrested are also included,

it can be assumed that the total number tripled. Many wives of war disabled or

war widows were compelled to earn money for their families in this way.

In many

grotesque and exaggerated pictures by George Grosz and Otto Dix, prostitution symbolizes

the general corruptibility and disi ntegration of society; it stands for moral

decadence on all levels. The women artists see things differently: in a

detached manner and without prejudice, the “Flaneur” Jeanne Mammen focuses her

attention on the camaraderie among the women. Elfriede Lohse - W ächtler

herself lived for a while in St. Pauli in Hamburg and depicted the milieu with

sympathy and humorous melancholy.

THE NEW WOMAN

During the Weimar Republic

women took over new professions in large numbers and became telephonists,

shorthand typists, and saleswomen. In many cases they formed the army of workers,

but thanks to the liberal laws women now also frequently became doctors,

academics, and political activists. As producers and consumers they took part

in cultural life, wrote, published magazin es, painted and illustrated, and

disc overed the new mass media.

The “women’s question” dominated political debates about

abortion and contraception, marital rights, prostitution, and women’s wages, as

well as fashion and everyday culture. The figure of the boyish garçonne with a

masculine haircut became a highly popular image under the visual construct of

the new femininity in Germany during the 1920s. The bob reigned supreme, but

other masculine accessories such as the monocle, trouser suit, tuxedo, and cigarette

were paraded openly not only by film stars like Marlene Dietrich. Ultimately,

however, the New Woman remained a figure created by the media and a big - city

phenomenon; her heyday was brief and before long she was being oppressed and

forced into retr eat again by conservative tendencies.

PARAGRAPH 175 AND MAGNUS

HIRSCHFELD

From 1896, the sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld took a stand against the

discrimination and criminalization of homosexuals. He quoted Friedrich

Nietzsche: “ What is natural cannot be im moral.” Hirschfeld believed that the

causes of homosexuality were inherent, but compared them with congenital

malformations. For many years he and his fellow campaigners attempted unsuccessfully

bring about a change in the law with numerous publications an dpetitions to

the Reich government.

Hirschfeld was the first to obtain data relating to sexual characteristics and habits by means of anonymous questionnaires. Hirschfeld also coined the term »transvestite,« and used it as the title of a book in 1910 : Die Transvestiten, eine Untersuchung über den erotischen Verkleidungstrieb ( The Transvestites: The Erotic Drive to Cross - Dress ).

Hirschfeld established contact with Sigmund Freud as early as 1908 and hoped for further explanations about the causes of homosexuality through research into sexual hormones, although this did not occur during his lifetime. In his Institute for Sexual Research, which he established in Berlin in 1919, he offered consultation sessions and therapy which were in some cases free of charge for men, women, and young people. Hirschfeld fled to France in 1933 and died there in 1935.

Hirschfeld was the first to obtain data relating to sexual characteristics and habits by means of anonymous questionnaires. Hirschfeld also coined the term »transvestite,« and used it as the title of a book in 1910 : Die Transvestiten, eine Untersuchung über den erotischen Verkleidungstrieb ( The Transvestites: The Erotic Drive to Cross - Dress ).

Hirschfeld established contact with Sigmund Freud as early as 1908 and hoped for further explanations about the causes of homosexuality through research into sexual hormones, although this did not occur during his lifetime. In his Institute for Sexual Research, which he established in Berlin in 1919, he offered consultation sessions and therapy which were in some cases free of charge for men, women, and young people. Hirschfeld fled to France in 1933 and died there in 1935.

PARAGRAPH 218 IN THE WEIMAR

REPUBLIC

The prohibition of abortion was added to the Criminal Code of the

German Empire in 1871 under Paragraph 218. Not only the pregnant woman

undergoing the abortion could now be punished with a prison sentence; so, too,

could the person who carried out the termination. As an instrument of power in

birth politics the topic became the subject of a public debate shaped by lawyers,

doctors, the Churches, and political parties as well as by the women’s movement,

which was in the process of being formed. During the Weimar Republic the abortion

debate became a synonym for social criticism as well as a popular movement which

united a wide range of different progressive forces from the middle and worki ng

classes. The demand for the “right to one’s own body” gained further currency as

a result of women’s suffrage, which was introduced in 1918. This controversial subject

was taken up in countless books and plays as well as in art.

Until the end of

inflation in 1924 it was above all the poor working - class woman with numerous

children who was the main focus of the protests and who was seen as the victim

of social conditions, symbolized by the “compulsion to give birth” prescribed

by the state. More than any other work of art, the poster by Käthe Kollwitz serves

as an example of this period. The decisive impulses for the mobilization of the

population arose under the impression of the world economic crisis and the mass

unemployment which accompanied it. But all the attempts at repeal introduced into

the Reichstag in subsequent years by the USPD, SPD, and KPD failed. In spite of

the broad alliances, countless campaigns, and mass demonstrations they were unable

to bring about the abolition of the paragraph.

PORTRAITS AS A MIRROR OF SOCIETY

The New

Objectivity led to the creation of many portraits in which important

personalities in public life under the Weimar Republic were depicted. They incl

uded gallerists, journalists, and writers, as well as industrialists, doctors,

and scientists. In addition to actual individuals who at the same time served

as representatives of professions and functions, there were also mere “types” such

as the new phenomenon of the radio listener. The broadcasting company had

begun continuous transmission in 1923 and the number of owners of a radio set

increased from one million in 1926 to four million by 1932. Nonetheless the

new appliance remained an unusual accessory. It was not yet the medium of mass communication

which it would become during the 1930s.

Many portraits by Otto Dix, Christian

Schad, Rudolf Schlichter, and others show people with impassive expressions;

they look matter - of - fact, unruffled, cool, withdrawn. The artists express symbolically

through objects and details who they are or what characterizes them: these

items are painted as clearly as the people themselves. The fact that people are

shown on the same level as “things” or that, conversely, each “thing” is

afforded the same attention as a human individual, is often seen as being a

typical characteristic of the New Objectivity.

TOWN – COUNTRY – INDUSTRY

Machinery,

factories, works sheds, technical constructions, and smoking chimneys, together

wit h telegraph poles, bridges, and railroad stations are some of the most

frequently depicted subjects in the art of the New Objectivity. Machines were

portrayed like beings from a distant future, alien and mysterious. An

enthusiasm for technology was widespr ead in the Weimar Republic, but was greeted

with great skepticism by broad sections of the population and was violently

criticized.

The optimism with regard to progress which had been propagated in

the Wilhelminian Age was certainly confirmed by the wide r ange of new

inventions – radio, records, and film. And yet the introduction of assembly - line

work also clearly revealed the dark side of technological innovation: increased

productivity, economic efficiency, and rationalization led to work which was

harmful to health and in some cases also contributed to the mass unemployment.

The landscape as portrayed in the artistic works of the age is no longer nature

and idyll, but has been made subject to Man with great lack of consideration

and even brutality.

Although industrialization should actually be linked to

hectic bustle, the pictures show scenes devoid of humanity; the cities look

curiously clean and tidy, as if they are theatrical backdrops. They are cold,

above all profoundly melancholy pictures, full of te nsion which is being held

back only with great difficulty but which one day could result in an apocalypse

if released. The nose - diving aircraft in the pictures of Franz Radziwill look

like a prophetic anticipation of what was to come.

SPORT IN THE WEIMAR REPUBLIC

After the defeat of the First Wo rld War, sport replaced in many respects the

longing for competition and ways to test one’s strength. “ Sports reports

played a role similar to that played by army reports ten years previously, and

what had been the prisoner statistics and records of plunder had now become records

and race times,” wrote the historian Sebastian Haffner. The socialist workers’

gymnastics movement, in which the focus initially lay on the medically sound rehabilitation

of a workforce tha t suffered through monotonous factory jobs, gave way from

1919 to the “ Workers’ Gymnastics and Sports Federation” , in which the concepts

of competition and performance were combined with the new governing values of

the Republic, including the overcoming of class and gender barriers.

As in other areas of modern life, the

increasing “Americanization” of sport was also the subject of increasing

criticism. The Anglo - Saxon sporting culture, which since the nineteenth

centur y had subscribed to the slogan “Faster – higher – further” , and which

was characterized by increased performance and competition, clashed with the

German tradition of gymnastics and physical training in a group. Strongly antiliberal

and militarist associations like the German Gymnastic Federati on aimed instead

to use sport above all as a means of “Strengthening the German People” once more.

Widely different value systems and political worldviews clashed in the field of

sport as they did in the other areas.

SOCIAL TOPICS

“ Man has created an invidious sy stem – with a top and a bottom,” wrote George Grosz in 1922. “ A handful of people earn millions, while countless thousands have barely enough to survive on ... but what does that have to do with ‘art’? The fact that many painters ... still put up with these things without speaking out clearly against them ... My work lies in showing the oppressed the true faces of their masters. Man is not good; he is a beast.”

At the beginning of the 1920s, unemployment increased sharply because of inflation and then ro se again even more steeply from 1929 as a result of the Great Depression. Artists like Hannah Nagel and Oskar Nerlinger showed very directly the resulting dramatic rise in the number of suicides. Other topics included the representation of families and the working world of the lower classes, whereby artists of the ASSO (Association Revolutionary Artists of Germany) like Otto Griebel and Hans and Lea Grundig in particular aimed to influence the political situation actively through their art. As early as 1932 the artist Alice Lex - Nerlinger was arrested for her left - wing political work; she portrayed her time spent in a prison cell in two paintings.

“ Man has created an invidious sy stem – with a top and a bottom,” wrote George Grosz in 1922. “ A handful of people earn millions, while countless thousands have barely enough to survive on ... but what does that have to do with ‘art’? The fact that many painters ... still put up with these things without speaking out clearly against them ... My work lies in showing the oppressed the true faces of their masters. Man is not good; he is a beast.”

At the beginning of the 1920s, unemployment increased sharply because of inflation and then ro se again even more steeply from 1929 as a result of the Great Depression. Artists like Hannah Nagel and Oskar Nerlinger showed very directly the resulting dramatic rise in the number of suicides. Other topics included the representation of families and the working world of the lower classes, whereby artists of the ASSO (Association Revolutionary Artists of Germany) like Otto Griebel and Hans and Lea Grundig in particular aimed to influence the political situation actively through their art. As early as 1932 the artist Alice Lex - Nerlinger was arrested for her left - wing political work; she portrayed her time spent in a prison cell in two paintings.