Musée d'Orsay

18 September 2018 - 6 January 2019

Fondation Beyeler, Basel

3 February to 26 May, 2019

The

Musée d'Orsay, associated with the Musée Picasso-Paris, presents the

first exhibition on the blue and pink period of Pablo Picasso in France.

This exhibition offers an unprecedented gathering of masterpieces, some

never presented in France, and a new analysis of the years 1900-1906,

an essential phase in the artist's career.

The album shows the evolution of Picasso's painting year by year and comments on the central works of the exhibition, giving the reader an overview of the blue and pink period.

The album shows the evolution of Picasso's painting year by year and comments on the central works of the exhibition, giving the reader an overview of the blue and pink period.

Pablo Picasso Self-portrait© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Mathieu Rabeau © Succession Picasso 2018

In 1900, at age eighteen, Pablo Ruiz, who would soon begin signing his work Picasso, already had all the makings of a young prodigy.

His work was divided between academic paintings to please his father, a teacher who dreamed of an official career for his son, and more personal works inspired by his contact with avant-garde circles in Barcelona.

It is his salon painting which took him to Paris, having been selected to represent his country in the Spanish painting section of the Universal Exhibition. He presented the large canvas Last Moments, which he painted over in 1903 with his masterpiece Life:

Courtesy of www.PabloPicasso.org

Courtesy of www.PabloPicasso.org This marked the start of a period of intense creative activity punctuated by travel between Spain and the French capital, Paris. Between 1900 and 1906, Picasso’s work gradually shifted from a rich palette of Pre-Fauvist colours – which owes a great debt both to the post-Impressionism of Van Gogh and to Toulouse-Lautrec – to the almost monochrome blues of the Blue Period, followed by the rose shades of the Saltimbanques Period, and the ochre hues of Gósol.

For the first time in France, this exhibition will span the Blue and Rose Periods, organised as a continuum rather than as a series of compartmentalised episodes. It also aims to reveal Picasso’s early artistic identity and some of the enduring obsessions in his work.

“The strongest walls open at my passing”

When he arrived at the Gare d’Orsay in October 1900, Picasso plunged into a very vibrant contemporary art scene: he discovered the paintings of David and Delacroix, but also works by Ingres, Daumier, Courbet, Manet and the Impressionists.

Like other artists of his generation, the young painter was a great admirer of Van Gogh, as demonstrated by his transition several months after this first trip to Paris to painting with strokes of pure colour.

Some self-portraits reveal how the artist embraced and absorbed the successive influences of the “modern masters”. In the summer of 1901, his Self-Portrait in a Top Hat was a parting tribute to Toulouse-Lautrec, nightlife and the cabaret scene; and in Yo Picasso, he depicts himself as the new messiah of art - elegant, arrogant and provocative - in homage to Van Gogh.

Seven months later, in his blue Self-Portratit, Picasso makes another reference to the Dutch painter, not in terms of style, but in the pose of a misunderstood genius sporting a red beard. A comparison with the self-portrait he painted on his return from Gósol in 1906 reveals just how much the artist developed in the space of a few years. Here, Picasso is experimenting with a new idiom, restricting his palette to complementary shades of grey and pink and reducing his facial features to an oval mask shape.

Pablo PicassoWoman in Blue© www.bridgemanimages.com © Succession Picasso 2018

From Barcelona to Paris: Spanish influences

The eye-opening experience of Paris in 1900 was not the young Picasso’s sole source of inspiration. His trips to Málaga, Madrid, Barcelona and Toledo between two visits to Paris speak volumes about his attachment to Spain, and the work he produced at the start of the century draws both on the Catalan modernists and the Spanish Golden Age.

Picasso was active within the lively artistic scene which was developing around 1900 in certain avant-garde Spanish venues and publications. In Barcelona, the young artist was an avid enthusiast of the paintings of his elders, Santiago Rusiñol and Ramon Casas.

The eye-opening experience of Paris in 1900 was not the young Picasso’s sole source of inspiration. His trips to Málaga, Madrid, Barcelona and Toledo between two visits to Paris speak volumes about his attachment to Spain, and the work he produced at the start of the century draws both on the Catalan modernists and the Spanish Golden Age.

Picasso was active within the lively artistic scene which was developing around 1900 in certain avant-garde Spanish venues and publications. In Barcelona, the young artist was an avid enthusiast of the paintings of his elders, Santiago Rusiñol and Ramon Casas.

He spent a great deal of time at the Els Quatre Gats cabaret, haunt of the Barcelona bohemian crowd. It was at once a tavern, exhibition venue and literary circle, modelled on the famousChat Noir in Paris.

On 1 February 1900, Picasso held his first proper exhibition there, filling the space with approximately five hundred portrait drawings executed in a matter of weeks, and one oil on canvas -Last Moments- which he presented at the Universal Exhibition in Paris shortly afterwards.

When Picasso settled in Madrid for a few months in the winter of 1901, his work fluctuated between modernists illustrations for the magazine Arte Joven and more ambitious painting imbued with references to Velasquez (Woman in Blue).

The Vollard gallery exhibition

Picasso arrived at the Gare d’Orsay station for the second time in the spring of 1901, armed with a few pastels and paintings produced in Madrid and Barcelona. The Catalan dealer Pedro Mañach persuaded Ambroise Vollard, the renowned gallery owner of the Parisian avant-garde, to organise an exhibition of Picasso’s work in the early summer – a fine opportunity for an unknown foreigner who barely spoke a word of French.

He painted round the clock in his studio on the boulevard de Clichy, producing as many as three pictures a day. This frenzied activity generated the majority of the 64 paintings and the handful of drawings displayed in the exhibition, which was opened on 25 June on rue Laffitte.

Picasso’s work was diametrically opposed to that of the painter with whom he shared the gallery space. He contrasted the quintessentially Spanish scenes of the Basque painter Francesco Iturrino with subjects about typical life in Paris by day and by night.

The exhibition at the Vollard gallery closed on 14 July. It was a critical success and sales were respectable. It introduced Parisians to a Picasso who embraced and reworked the styles and motifs of the great modern artists Van Gogh, Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec. It made an impression on the young poet Max Jacob, who was keen to be introduced to the artist.

Pablo Picasso Seated Harlequin© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image of the MMA © Succession Picasso 2018

After the success of the Vollard exhibition, the autumn of 1901 was a period of introspection for the young painter, when his art took a new direction. In tandem with the cycle of paintings directly associated with the death of Casagemas, he produced a group of poignant works characterised notably by the appearance of the figure of Harlequin.

Picasso’s Seated Harlequin, lost in thought at a bistro table, forms part of a group of paintings of a similar format focusing on related themes. Their iconography draws both on the café scenes of Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet, and on the world of the saltimbanques (circus performers) which would soon dominate his pictorial world.

But it is from the recently deceased Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec from whom Picasso borrows the daringly fluid lines of his compositions. The black outlining and flat areas of colour in his paintings create “the impression of stained glass”, writes the art critic Félicien Fagus in 1902.

http://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/events/exhibitions/in-the-museums/exhibitions-in-the-musee-dorsay-more/page/1/article/picasso-47542.html?tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=649&cHash=47131641af

Pablo Picasso (1881-1973)Acrobat with a ball 1905 Oil on canvas H. 147; W. 95 cmMoscow, The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts© Image The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow © Succession Picasso 2018

The death of Picasso’s friend Casagemas

Carles Casagemas, the son of the American consul in Barcelona, forged a close friendship with Picasso in the summer of 1899. He shared a studio with him in Barcelona and then accompanied him to Paris in the autumn of 1900.

His failed love affair with a young model prompted him to commit suicide on 17 February 1901 in a Montmartre restaurant, after he fired a shot at his lover and missed. Picasso heard the news while he was in Madrid.

When he returned to Paris several months later, the artist addressed this tragic event in a painting produced in the very studio where Casagemas spent his final hours.

In the summer, The Death of Casagemas, with its Fauvist expressionism and thick layers of impasto, recalls of some of Picasso’s works exhibited in the Vollard exhibition.

The palettes of the other portraits of the deceased man are tinged with the blue that Picasso gradually introduces into his paintings that autumn. Blue is also the dominant colour in his large painting Evocation, the last composition in the cycle, which parodies the binary structure of El Greco’s Burial of the Count of Orgaz in an irony-tinged final farewell.

“Of Sadness and Pain”

Pablo PicassoThe Death of Casagemas© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Mathieu Rabeau © Succession Picasso 2018

Carles Casagemas, the son of the American consul in Barcelona, forged a close friendship with Picasso in the summer of 1899. He shared a studio with him in Barcelona and then accompanied him to Paris in the autumn of 1900.

His failed love affair with a young model prompted him to commit suicide on 17 February 1901 in a Montmartre restaurant, after he fired a shot at his lover and missed. Picasso heard the news while he was in Madrid.

When he returned to Paris several months later, the artist addressed this tragic event in a painting produced in the very studio where Casagemas spent his final hours.

In the summer, The Death of Casagemas, with its Fauvist expressionism and thick layers of impasto, recalls of some of Picasso’s works exhibited in the Vollard exhibition.

The palettes of the other portraits of the deceased man are tinged with the blue that Picasso gradually introduces into his paintings that autumn. Blue is also the dominant colour in his large painting Evocation, the last composition in the cycle, which parodies the binary structure of El Greco’s Burial of the Count of Orgaz in an irony-tinged final farewell.

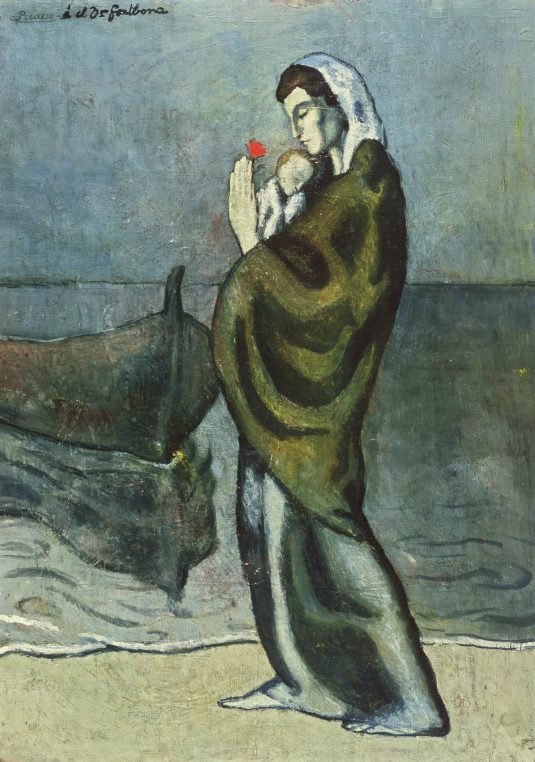

In the autumn of 1901, Pablo Picasso went to Saint-Lazare women’s prison in Paris. The inmates were mainly prostitutes, some of whom were incarcerated with their children. Women infected with venereal diseases were singled out with bonnets.

These visits initiated a series of paintings on the theme of motherhood, produced in the final months of the year.

When the artist returned to Barcelona in late January 1902, he continued to paint female figures embodying loneliness and misfortune. This marked the beginning of the Blue Period, characterised by the dominance of this colour, sentimental themes and a quest for expressive forms.

Pablo Picasso Woman and child on the shore© www.bridgemanimages.com © Succession Picasso 2018

Pablo PicassoWailing woman© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Béatrice Hatala © Succession Picasso 2018

Although the term Blue Period instantly conjures up painting, Picasso’s art extends well beyond this medium.

Paintings, sculptures, drawings and engravings all stem from the same aesthetic experiments, the same quest to express suffering.

These ink and pencil sheets, which belong to the significant body of graphical work produced between 1902 and 1903 depict the suffering, emaciated bodies of men and women and demonstrate mastery of a wide array of techniques. They reveal the virtuosity of Picasso the draughtsman.

The paintings offer numerous variations of the colour blue. For Picasso, “the need to paint in this way was driven from within”, but he was probably also influenced by his habit of painting at night by the light of a paraffin lamp.

In tandem with these tragic depictions of the destitute, whose deformed limbs are reminiscent of paintings by El Greco, Picasso produced portraits of his Barcelonan friends through lenses of both benevolence and sarcasm.

Pablo PicassoLa Célestine© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée national Picasso-Paris) / Mathieu Rabeau © Succession Picasso 2018

In Paris and Barcelona, between 1901 and 1903, Picasso produced numerous lively erotic drawings which verge on caricature and which offer a counterpoint to the somber, melancholic paintings of destitute figures in his Blue Period.

They are an extension of his exploration of the shady world of brothels, made manifest in his paintings by the prostitutes of the Saint-Lazare prison, and by the portrait La Célestine inspired by the Barcelonan brothel keeper Carlota Valdivia.

These works, long kept hidden, were in many cases quickly sketched on the back of business cards for his friend Sebastià Juñer-Vidal’s factory, but they represent a recurring theme in Picasso’s work: the permanent and inextricable association between love and death.

Life

Life was painted in the spring of 1903, and represents the culmination of the aesthetic experiments carried out by Picasso since the start of the Blue Period. It is painted on top of Last Moments, which Picasso presented at the Universal Exhibition in 1900.

A number of sketches and an x-ray analysis of the painting reveal the development of the composition and figures. Although the man on the left was initially a self-portrait, he eventually adopts the features of Carles Casagemas, Picasso’s friend who committed suicide in February 1901 after a failed love affair. The artist also planned to position an easel and winged figure in the centre of the picture.

The final painting has given rise to many different interpretations. It is often seen as an allegory for the cycle of life from childhood – embodied by the pregnant woman – to death, symbolised by the crouching figure in the background, and therefore reflects the metaphysical ideas of certain artists such as Paul Gauguin.

"Au rendez-vous des poètes"

It was probably shortly after moving into the Bateau-Lavoir, in May 1904, that Picasso wrote this phrase in blue pencil above the door of his Montmartre studio: "Au rendez-vous des poètes" (Poets’ meeting place).

At the time, Picasso was living in an artists’ colony on the Butte with several of his fellow countrymen, such as Paco Durrio, and had a whole host of poet friends including Max Jacob, Guillaume Apollinaire and André Salmon.

They were some of his earliest admirers and they instilled in him an appreciation for the new style of poetry which pervades Picasso’s works of the Rose Period.

Towards rose

In the early months of 1905, building on the works produced in the last weeks of 1904, Picasso broadened his colour range.

This subtle transition took place without any major change in the style of his figures, whose mannerism and Expressionist distortions are similar to those of the Blue Period.

The artist painted a number of pictures inspired by Madeleine, with whom he was romantically involved.

These portraits trace the gradual move away from monochrome blue towards a nuanced palette ranging from the vivid red clothing of Woman with a Crow to the milky-white complexion of his Woman in a Chemise.

In the summer of 1905, Picasso’s trip to the Netherlands awakened an interest in traditional costumes and picturesque landscapes. The shapely bodies of the women of Schoorl fostered Picasso’s growing interest in the use of sculptural effects in painting.

Pablo PicassoThe acrobat family© Gothenburg Museum of Art / Photo Hossein Sehatlou © Succession Picasso 2018

The Saltimbanque cycle – which Picasso developed simultaneously in painting, drawing, engraving and sculpture – spans the period from late 1904 to the end of 1905.

There are two main themes: the family and fatherhood of Harlequin, and the circus which combines the Commedia dell’arte character and the lithe figures of acrobats, jesters and hurdy-gurdy musicians.

These two threads come together in the large gouache Family of Saltimbanques with a Monkey, which featured in the exhibition at the Serrurier gallery in 1905.

These compositions, inspired by the troupe of the Médrano circus located at the corner of the rue des Martyrs and boulevard Rochechouart, are characterised by their seriousness.

Picasso is less interested in the show, usually excluded from the frame, than in the other aspects of their lives, capturing a medial space between public and private worlds where in the most banal triviality and the most sublime grace converge.

Where we might expect movement, lightness and cheerfulness, Picasso offers static, compact and melancholic painting, culminating in Family of Saltimbanque which he worked on during the spring. This masterpiece from 1905 forms part of the Chester Dale collection, but is not available for loan under the terms of the bequests policy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington.

From rose to ochre

Pablo Picasso Boy Leading a

Horse© Succession Picasso 2018 / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In

early 1906, the paintings of Ingres, which featured in a retrospective

at the Salon d’Automne in 1905, inspired Picasso to paint the large

composition The Watering Place , which he later abandoned and for which he lifted Boy Leading a Horse .

The artist’s work was imbued with a new classicism, and the Rose Period was transitioning towards ochre.

These trends became more distinct during his trip to Gósol from May to August 1906. There is a strange synergy between his work and the spectacular landscape of this isolated village in the Catalan Pyrenees.

These trends became more distinct during his trip to Gósol from May to August 1906. There is a strange synergy between his work and the spectacular landscape of this isolated village in the Catalan Pyrenees.

Picasso’s encounter with Romanesque sculpture and Iberian art the previous winter at the Louvre museum prompted a return to his roots which reinforced his interest in the work of Gauguin.

Over a period of several weeks, both his sculpture and paintings become characterised by an extreme simplification of form and space, forecasting and initiating the aesthetic revolutions which follow. Leo and Gertrude Stein facilitated and supported this ongoing development by providing intellectual affirmation and financial assistance.

The major turning point

In Gósol, Picasso embarked on a new path, influenced by the Classical Antiquity of the Mediterranean just as by the paintings of Ingres.

There, in the solitude of a summer spent with his partner Fernande, he undertook his first critique of the sensual escapism of The Turkish Bath, 1862, Paris, Musée du Louvre), beginning in a series of works on the theme of hairdressing.

When the artist returned to Paris, he refocused his attention almost exclusively on the female body, to which he devoted a number of works, rejecting illusionist techniques in favour of a new expressive language: composing images by interlacing basic shapes with a colour palette restricted to shades of ochre.

The gradual emergence of this radically new vocabulary represents the first application of Cézanne’s theory of the geometrisation of volumes.

Picasso’s experimental approach, in which the relationship between painting, sculpture and engraving plays a key role, produced

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (New York, Museum of Modern Art) in 1907, which blazes the trail for the great adventure of Cubism.

Exhibition Album

Claire Bernardi, Stéphanie Molins, Emilia Philippot

Musée d'Orsay / Hazan - 2018

Paperback, 21,6× 28,8 cm - 48 p. - 40 ill.

ISBN : 978-2-75411-480-6

Bilingual french, English