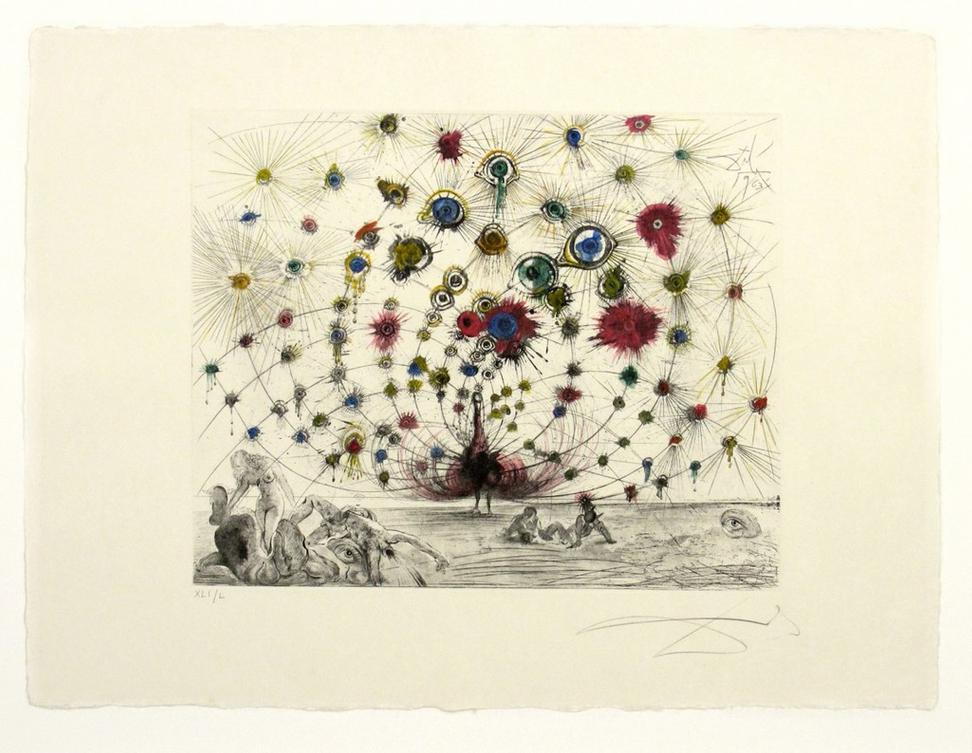

Salvador Dalí, Argus in Color, 1963(ACA Galleries)

ACA Galleries in New York will present Salvador Dalí, a solo exhibition featuring selected etchings, Aubusson tapestries and drawings from the Argillet Collection, from January 10 to March 9, 2019.

Dalí and Pierre Argillet began working together in 1959 and produced nearly 200 etchings over a 15 year period. They are noted for their attention to detail with wide-ranging themes such as mythology, Faust, bullfights, as well as the writings of Apollinaire, Chairman Mao, and Don Juan among others. The prints they produced during this fertile collaboration have been shown at museums throughout the world including Musée Boijmans, Rotterdam; Musée Pushkin, Moscow; Kunsthaus, Zurich; Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart; Isetan Museum of Art, Tokyo; and Daimaru Art Museum, Osaka, among others.

Salvador Dalí was a Spanish painter, sculptor, graphic artist and designer who joined the Surrealist movement in 1929. One of the most legendary and eccentric of the group, Dalí formulated the methodology of Critical Paranoia which encouraged artists to unlock their subconscious. He lived in the United States from 1940 – 1955 before returning to Spain. There are two art museums dedicated to Dalí: one in Figueras, Spain and the other in St. Petersburg, Florida.

Salvador Dalí, Bullfight, tapestry

ACA Galleries

Salvador Dalí (b. 1904 – 1989) is regarded as one of the most iconic

artists of the 20th century and with good reason. His art was

multi-faceted and trailblazing and his personal life was riddled with

unlikely twists. From being expelled from art school (twice) to his

little-known collaboration with Chupa Chups lollipops (the logo he

designed for them in 1969 is still used to this day), Dalí’s life has

proven to be rich with both stories and masterworks that still capture a

modern audience’s imagination.

In fact, Dalí even experienced such fame during his own lifetime that he often treated large groups of friends to dinner by settling the check with a drawing on the reverse—knowing that even a small doodle by his hand would likely prevent the check from ever being cashed.

In fact, Dalí even experienced such fame during his own lifetime that he often treated large groups of friends to dinner by settling the check with a drawing on the reverse—knowing that even a small doodle by his hand would likely prevent the check from ever being cashed.

This degree of fame was not accidental. Dalí was arguably the

first modern artist to cultivate a personal brand in any contemporary

sense and his talent for doing so proved remarkably skillful. Dalí

displayed a natural knack for courting controversy and intrigue. He once

duped Yoko Ono into buying a single strand of his moustache for $10,000

dollars that was, in fact, a dried blade of grass from a nearby park.

It was anecdotes like this which endeared him to the fashionable set of

Café Society in Europe in the 1950s.

Yet perhaps the most enduring story of Dalí’s life—and most closely tangled up with the genre-defining art he produced—is the story of his love affair with neé Elena Ivanovna Diakonova, styled more commonly by the single name: Gala.

Yet perhaps the most enduring story of Dalí’s life—and most closely tangled up with the genre-defining art he produced—is the story of his love affair with neé Elena Ivanovna Diakonova, styled more commonly by the single name: Gala.

Salvador Dalí was not Gala’s first love affair with a famous

Surrealist artist, nor would he be her last. When Dalí met his future

wife, muse, and business manager she was already married. Her husband,

Paul Éluard—a French poet and founding member of André Breton’s original

Surrealism movement—had met Gala when they were seventeen and

convalescing at the same sanitorium in Switzerland. They married shortly

before Éluard left to fight in World War I and afterwards moved to a

suburb of Paris.

It was at their house in Saint-Brice that the famous Surrealist painter Max Ernst would eventually relocate, leaving behind his wife and son to move in with Gala and Éluard and enter into a ménage-à-trois that would last three years, from 1924 to 1927.

It was at their house in Saint-Brice that the famous Surrealist painter Max Ernst would eventually relocate, leaving behind his wife and son to move in with Gala and Éluard and enter into a ménage-à-trois that would last three years, from 1924 to 1927.

Mythology Suite: Judgment of Paris

Two years later Gala met Dalí when he was visiting Paris, about to

collaborate with Luis Bruñuel on Un Chien Andalou, the Surrealist film

that would be Dalí’s first large-scale artistic success and launch his

career—much of which Gala would oversee and steer. The connection

between the two was instant and would endure the remainder of their

lives despite their numerous affairs, unusual sexual arrangements, and

periods of estrangement.

Gala was ten years Dalí’s senior and the age difference enraged

Dalí’s father who was already incensed by a particular work of

Surrealist art in which Dalí included the inscription: “Sometimes, I

spit for fun on my mother’s portrait.” Dalí’s relationship with his

parents had always been fraught. His birth came just nine months after

his older brother’s death, who was also named Salvador, and when Dalí

was five-years-old his parents had taken him to his brother’s grave and

explained that Dalí was a reincarnation of the child they had lost—an

idea he continued to accept throughout his adult life.

When Dalí and Gala entered into their civil partnership, Dalí was banished from his paternal house in Cadaqués and disinherited. The couple responded by renting a fisherman’s cabin in nearby Port Lligat, which they gradually expanded by buying up neighbouring cabins as well, quilting them into a much beloved villa as Gala deftly guided them away from financial insolvency. Over the next five years until their marriage in 1934, Dali would often sign his paintings not with his own name but with Gala’s, writing: “It is mostly with your blood, Gala, that I paint my pictures.”

When Dalí and Gala entered into their civil partnership, Dalí was banished from his paternal house in Cadaqués and disinherited. The couple responded by renting a fisherman’s cabin in nearby Port Lligat, which they gradually expanded by buying up neighbouring cabins as well, quilting them into a much beloved villa as Gala deftly guided them away from financial insolvency. Over the next five years until their marriage in 1934, Dali would often sign his paintings not with his own name but with Gala’s, writing: “It is mostly with your blood, Gala, that I paint my pictures.”

During the summers, Dalí painted at the villa. Many of his most influential works were created there, including the Persistence of Memory

and his recurring motif of melted clocks. During the winters, Gala and

Dalí travelled to Paris and New York, where Gala organized dinners,

meetings, and balls with collectors, gallerists, and other artists who

would prove to be essential to Dalí’s growth.

As Dalí’s fame increased abroad, tension began to mount with Breton’s Surrealists, among whom Dalí had got his start. 1934—the same year during which Dalí and Gala were wed—saw both Dalí lauded by socialites in New York at a “Dalí Ball” and rebuked by his artistic contemporaries at a “Dalí Trial” organized by Breton himself in order to determine whether Dalí should be permitted to remain a member of the Surrealists. The group was becoming ever more communist in its sensibilities and Dalí was and would continue to remain apolitical throughout his life—often returning to Spain even during Franco’s dictatorship during when many of the cultural elite fled.

As Dalí’s fame increased abroad, tension began to mount with Breton’s Surrealists, among whom Dalí had got his start. 1934—the same year during which Dalí and Gala were wed—saw both Dalí lauded by socialites in New York at a “Dalí Ball” and rebuked by his artistic contemporaries at a “Dalí Trial” organized by Breton himself in order to determine whether Dalí should be permitted to remain a member of the Surrealists. The group was becoming ever more communist in its sensibilities and Dalí was and would continue to remain apolitical throughout his life—often returning to Spain even during Franco’s dictatorship during when many of the cultural elite fled.

In response to his trial, Dalí notoriously replied: “The

difference between the Surrealists and I is, I myself am Surrealism.”

And this was true. As Dalí became closer to Gala, he also drew closer to

developing a style that put him farther away from the other members of

Surrealism.

Unlike many relationships between artists and their muses, that between Dalí and Gala would not expire as she grew older. Instead, Dalí went on to use Gala as a model for works well into her seventies and her name often appears in the titles of works in addition to her image. In 1968 he bought her a derelict castle in Pubol, Spain, where she would spend her retirement until her death and where Dalí, fascinatingly, was not allowed to visit without her explicit permission in writing.

Unlike many relationships between artists and their muses, that between Dalí and Gala would not expire as she grew older. Instead, Dalí went on to use Gala as a model for works well into her seventies and her name often appears in the titles of works in addition to her image. In 1968 he bought her a derelict castle in Pubol, Spain, where she would spend her retirement until her death and where Dalí, fascinatingly, was not allowed to visit without her explicit permission in writing.

“The difference between the Surrealists and I is, I myself am Surrealism” – Salvador Dalí

Dalí not only accepted the rules surrounding Gala, her privacy,

and her young male lovers—many of them artists—he romanticized them,

describing their arrangement as “the neurotic ceremony of courtly love.”

However, Dalí was never more direct in his explanation of the role his

love affair with Gala played in both his art and life than in his

memoirs, rapturously titled The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí.

In them, he compares her to Gravid, the title of a book by W.

Jensen, the main character of which was Sigmund Freud, another

significant influence in Dalí’s work. In the story, the character of

Gravida brings psychological healing to Freud. Dalí describes her

presence in his own world as such: “She was destined to be my Gravida,

the one who moves forward, my victory, my wife.” And it is this love

story that still captures the imaginations of Dalí admirers today. In a

life so richly packed with intriguing detail, the narrative of Dalí and

Gala—and both of their relationships to his art—stands out.

Caroline Calloway, Courtesy ACA Galleries

Caroline Calloway, Courtesy ACA Galleries