Monday, July 30, 2012

Winslow Homer's Depictions of Maritime Catastrophe and Rescue

Shipwreck! Winslow Homer and “The Life Line” The Philadelphia Museum of Art September 22–December 16, 2012

While living in a tiny fishing village in England in 1881-82, the American artist Winslow Homer was profoundly moved by the sight of a shipwreck that would focus his imagination on the power and peril of the sea.

His art took on a new seriousness and drama, demonstrated in a major painting made soon after his return to the United States: The Life Line (1884),one of his greatest popular and critical successes. A masterpiece owned by the Philadelphia Museum of Art for almost 90 years, The Life Line is the centerpiece of an exhibition about the making and meaning of an iconic American image of rescue at sea.

Celebrating modern heroism and the thrill of unexpected intimacy between strangers thrown together by disaster, Shipwreck! Winslow Homer and “The Life Line” contains works by Homer complemented by a range of precedents in the shipwreck and rescue genre including paintings, watercolors, etchings, engravings, sketches and ceramics ranging in date from the mid-17th to the early 20th centuries. The Philadelphia Museum of Art will be the only venue for this important exhibition, which includes fragile and rarely seen watercolors, prints, and drawings.

“The Museum contains one of this nation’s greatest collections of American art and many of our finest exhibitions are inspired by it,” notes Timothy Rub, The George D. Widener Director and Chief Executive Officer. “We are delighted to focus on Homer’s The Life Line in this important exhibition, as it places a major artistic milestone in an illuminating context within the traditions of marine painting and American art and history.”

The exhibition explores the related themes of the exhilaration of ocean travel, disaster on the high seas, and romantic rescue, while examining the creative contributions of one of this country’s greatest artists to the rich tradition of marine painting.

The opening gallery introduces the importance of ocean travel to the Eastern seaboard of the United States and its significance to Boston-born Homer, and includes the watercolor Clear Sailing (c. 1880; Philadelphia Museum of Art). Typical of Homer’s lighthearted work from this period, the painting shows children watching white-sailed boats on a calm and sun-drenched harbor.

The next section takes on a darker tone, surveying the theme of shipwreck during the first great age of marine painting from the 17th through the 19th centuries. The aftermath of a shipwreck for those waiting onshore follows, with works based on Homer’s experience in the English village of Cullercoats, on the North Sea in 1881–2, where he witnessed the wreck of the Iron Crown.

Other sections look at the theme of the romantic rescue of the helpless damsel, while “Heroes of the Coastline: The Rise of the Unites States Life Saving Service” examines the real life historical context of these rescue scenes. ”Heroes of the Coastline” also tells the story of the spectacularly successful reform of the shoddy American coastal defenses, beginning with the establishment of the United States Life Saving Service in 1871, followed by the integration of new technology and the employment of trained personnel.

Against this backdrop of tradition and recent innovation, Homer created a painting of startling modernity and old-fashioned romance. A full section of the exhibition is dedicated to the making of The Life Line, including preparatory drawings and etchings that suggest changes the artist made before arriving at the final image. These alterations, seen in revisions visible on the surface of the painting and in recent X-radiographs and infrared photographs, demonstrate Homer’s wish to focus the composition on the figure of the woman by obscuring the visage of his hero and tempering the erotic narrative of intertwined figures to suit the buttoned-up morals of the Victorian period. A section containing a small group of prints and paintings made by Homer after 1884 introduces his late marine paintings, with their themes of anxiety, struggle, and stoicism in the face of nature.

Human narratives receded as more abstract treatments of elemental conflict—land, sea, and sky—came to dominate the last two decades of the artist’s career, represented by paintings such as Winter Coast, 1890 (Philadelphia Museum of Art), a study in the eternal battle of majestic natural forces.

When The Life Line was first exhibited at the National Academy of Design in New York in 1884 it became an instant sensation. Demonstrating a recent innovation in life saving technology, the breeches buoy, Homer’s painting is at once realistic and romantic, demure and suggestive. The drama of the roiling seas and realism of the breeches buoy is softened by the form of a voluptuous woman, her soaked dress clinging to her curves, being ferried to safety by an anonymous rescuer whose face is obscured by the woman’s red scarf blowing in the gale.

“Homer was at the peak of his powers when he painted The Life Line , which has never before been the subject of intensive study. It was one of the triumphs of his career, and it has remained one of his best-known paintings. This exhibition will explore how The Life Line was made, how it was understood in its own day, and why it has become such an icon of American art,” said Kathleen Foster, the Robert L. McNeil, Jr. Curator of American Art. “By placing The Life Line in the context of Homer’s work and alongside popular images of rescue at sea published by the likes of Currier & Ives, we can see how Homer drew from both old and new sources to create a strikingly modern image.”

About the catalogue: The Philadelphia Museum of Art, in association with Yale University Press, will publish a 104-page catalogue with 110 color plates and five black and white illustrations. Written by curator Kathleen Foster, Shipwreck! combines a close analysis of Homer’s masterpiece with an engaging look at historical images of disaster and rescue.It will be available in the Museum Store in paperback ($20) beginning September. It also can be purchased by calling 1-800-329-4856, or online at philamuseum.org. ISBN: 978-0-87633-238-2.

About the artist: A painter, illustrator, and etcher, Winslow Homer (1836-1910), is considered to be the greatest pictorial poet of outdoor life in American history. Dedicated to subjects based on the national experience, from Civil War to rural life and the native landscape, Homer was an artist of power and individuality whose images rise beyond realism to engage with the larger relationship of man to nature.

More Images:

The Wreck of the "Atlantic" - Cast up by the Sea, 1873. Winslow Homer, American, 1836 - 1910. Wood engraving, Image: 9 1/8 x 13 7/8 inches (23.2 x 35.2 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with the Lola Downin Peck Fund from the Carl and Laura Zigrosser Collection, 1965.

The Wreck of the Iron Crown, 1881. Winslow Homer, American, 1836 - 1910. Transparent and opaque watercolor over graphite and charcoal, Sheet: 20 1/4 x 29 7/16 inches (51.4 x 74.8 cm). Carleton Mitchell and Ruth Mitchell Collection, on extended loan to The Baltimore Museum of Art.

Shipwreck on a Rocky Coast, c. 1640. Bonaventura Peeters, Flemish (active Antwerp), 1614 - 1652. Oil on panel, 18 13/16 x 28 5/8 inches (47.8 x 72.7 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with the Director's Discretionary Fund, 1970.

The Shipwreck, 1772. Claude-Joseph Vernet, French, 1714 - 1789. Oil on canvas, 44 11/16 x 64 1/8 inches (113.5 x 162.9 cm). Framed: 49 1/8 x 68 1/16 x 3 inches (124.8 x 172.9 x 7.6 cm). National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund and Chester Dale Fund 2000.22.1.

Wednesday, July 25, 2012

101 ICONIC PRINTS BY AMERICAN MASTER JASPER JOHNS

One of the most celebrated artists of the modern era, Jasper Johns (b. 1930) transformed the field of printmaking. For over 50 years, he has tested the medium’s boundaries, reinventing subjects like targets, American flags, and images from art history in endless variation. The first exhibition of his work at The Phillips Collection features prints from each decade, with groundbreaking examples of lithography, intaglio, silkscreen, and lead relief. Jasper Johns: Variations on a Theme is on view June 2 through Sept. 9, 2012 at The Phillips Collection, 1600 21st Street, NW | Washington, DC 20009 | 202-387-2151

The exhibition spans Johns’s entire printmaking career, beginning with his first experiments and culminating in 2011. In 1960, Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) founding director Tatyana Grosman encouraged Johns to work on lithographic stones, and he completed five prints and began his celebrated 0–9 series. Inspired, Johns saw printmaking as a way to transform ideas he had already developed in painting, drawing, and sculpture.

Johns mines art history, including his own work, to repeat and vary motifs. Fragments–According to What (1971), for example, excavates six details from his 1964 painting, According to What. The exhibition brings together all six prints from this important series. In 1976, Johns partnered with writer Samuel Beckett to create Foirades/Fizzles on view in the exhibition. The book includes 33 etchings, which revisit an earlier work by Johns and five text fragments by Beckett.

“Jasper Johns’s persistent experimentation not only transformed printmaking but set the standard for contemporary art,” says Phillips Director Dorothy Kosinski. “A champion of visionary American artists since 1921, the Phillips is proud to present over five decades of Johns’s graphic achievements, including our own The Critic Sees (1967). We are deeply grateful to the John and Maxine Belger Foundation whose collaboration makes a project on this scale possible.”

Opening with early prints like Target (1960), the exhibition unfolds to reveal the artist’s evolving interests. At the end of the 1960s, he experiments with etching in 1st Etchings Portfolio (1968). In the 1970s, an abstract aesthetic emerges with a crosshatch motif in works like Corpse and Mirror (1976). In the 1980s, autobiographical elements enter Johns’s work such as a tracing of the artist’s shadow in The Seasons (1987). In the 1990s, images from art history appear in After Holbein (1993–94) and Green Angel (1991). Johns’s latest prints, Fragments of a Letter (2010) and Shrinky Dinks 1–4 (2011), layer text, cubist forms, and hand gestures from American Sign Language.

Johns’s collaborations with master printers, including those at ULAE in New York and Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles, are essential to his work. They empowered him to test methods unprecedented in the history of the medium. He said: “It’s the printmaking techniques that interest me . . . the technical innovation possible.” Six ingenious lead reliefs realized at Gemini G.E.L. from 1969 to 1970 are featured in the exhibition, as are several important collaborations with ULAE including Decoy (1971), considered Johns’s first offset print, Voice 2 (1982), as well as the artist’s newest prints.

Jasper Johns: Variations on a Theme is organized by The Phillips Collection in collaboration with the John and Maxine Belger Foundation. Exhibition curator is Phillips Assistant Curator Renée Maurer.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011, Jasper Johns is a central figure in modern and contemporary art. His work is represented in nearly every major museum collection and has been the subject of one-person exhibitions throughout the world. Born in Georgia in 1930 and raised in South Carolina, Johns grew up wanting to be an artist. He moved to New York City in his 20s and emerged as a force in the American art scene in 1958 with a solo show at Leo Castelli Gallery from which the Museum of Modern Art purchased three pieces. For over 50 years Johns has challenged the possibilities of printmaking, painting, and sculpture, laying the groundwork for a wide range of experimental artists. He represented the United States at the Venice Biennale in 1988 and was awarded the Grand Prix. Johns currently lives and works in Sharon, Conn., and the Caribbean island of Saint Martin.

1) Jasper Johns, Flags II, 1970. Lithograph, 34 x 25 in. Published by Universal Limited Art Editions. John and Maxine Belger Foundation © Jasper Johns and ULAE / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

2) Jasper Johns, Figure 1, 1969. Lithograph, 37 3/4 x 31 in. Published by Gemini G.E.L. John and Maxine Belger Foundation © Jasper Johns and Gemini G.E.L./Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

3) Jasper Johns, Target, 1960. Lithograph, 22 1/2 x 17 1/2 in. Published by Universal Limited Art Editions. John and Maxine Belger Foundation © Jasper Johns and ULAE / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

4) Jasper Johns, Bread, 1969. Embossing with object, 23 x 17 in. Published by Gemini G.E.L. John and Maxine Belger Foundation © Jasper Johns and Gemini G.E.L. / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

5) Jasper Johns, Decoy, 1971. Lithograph with die cut, 41 x 29 in. Published by Universal Limited Art Editions. John and Maxine Belger Foundation © Jasper Johns and ULAE / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

6) Jasper Johns, Savarin, 1977. Lithograph, 45 x 35 in. Published by Universal Limited Art Editions. John and Maxine Belger Foundation © Jasper Johns and ULAE / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

7) Jasper Johns, Fragment—According to What (Leg and Chair), 1971. Lithograph, 35 x 30 in. Published by Gemini G.E.L. National Gallery of Art © Jasper Johns and Gemini G.E.L. / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

ABOUT THE PHILLIPS COLLECTION

The Phillips Collection is one of the world’s most distinguished collections of impressionist and modern American and European art. Stressing the continuity between art of the past and present, it offers a strikingly original and experimental approach to modern art by combining works of different nationalities and periods in displays that change frequently. The setting is similarly unconventional, featuring small rooms, a domestic scale, and a personal atmosphere. Artists represented in the collection include Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Vincent van Gogh, Edgar Degas, Henri Matisse, Pierre Bonnard, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Paul Klee, Claude Monet, Honoré Daumier, Georgia O’Keeffe, Arthur Dove, Mark Rothko, Milton Avery, Jacob Lawrence, and Richard Diebenkorn, among others. The Phillips Collection, America’s first museum of modern art, has an active collecting program and regularly organizes acclaimed special exhibitions, many of which travel internationally. The Intersections series features projects by contemporary artists, responding to art and spaces in the museum. The Phillips also produces award-winning education programs for K–12 teachers and students, as well as for adults. The museum’s Center for the Study of Modern Art explores new ways of thinking about art and the nature of creativity, through artist visits and lectures, and provides a forum for scholars through courses, postdoctoral fellowships, and internships. Since 1941, the museum has hosted Sunday Concerts in its wood-paneled Music Room. The Phillips Collection is a private, non-government museum, supported primarily by donations.

Also:

Fragment—According to What: Hinged Canvas 1971 lithograph, working proof with crayon, chalk, and graphite National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund and Special Friends of the National Gallery of Art. Art © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Lyonel Feininger: At the Edge of the World

Lyonel Feininger, The White Man, 1907, Oil on canvas, 26 7/8 x 20 5/8 in. (68.3 x 52.3 cm), Collection of Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza, © 2011 Lyonel Feininger Family, LLC./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

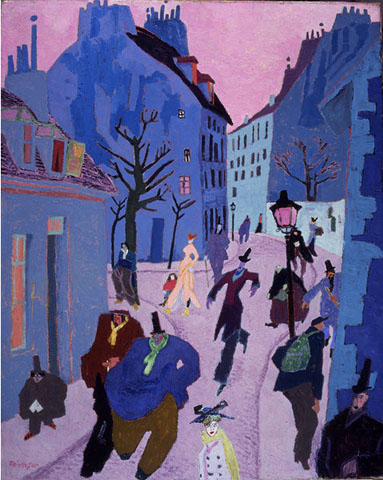

Lyonel Feininger, In a Village Near Paris (Street in Paris, Pink Sky), 1909. Oil on canvas, 39 3/4 x 32 in. (101 x 81.3 cm) University of Iowa Museum of Art, Iowa City; gift of Owen and Leone Elliott 1968.15 © Lyonel Feininger Family, LLC./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Lyonel Feininger, Carnival in Arcueil, 1911. Oil on canvas, 41 3/10 × 37 8/10 in (104.8 × 95.9 cm). Art Institute of Chicago; Joseph Winterbotham Collection 1990.119, © Lyonel Feininger Family, LLC./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Photograph © The Art Institute of Chicago

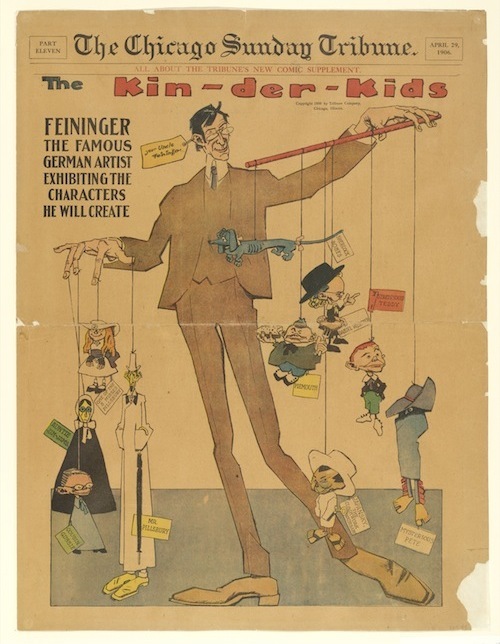

Lyonel Feininger has long been recognized as a major figure of the Bauhaus, renowned for his romantic, crystalline depictions of architecture and the Baltic Sea. Yet the range and diversity of his achievement are less well known. Lyonel Feininger: At the Edge of the World, the artist’s first retrospective in the United States in forty-five years, was the first ever to incorporate the full breadth of his art by integrating his well-known oils with his political caricatures and pioneering Chicago Sunday Tribune comic strips; his figurative German Expressionist compositions; his architectural photographs of Bauhaus and New York subjects; his miniature hand-carved, painted wooden figures and buildings, known as City at the Edge of the World; and his ethereal late paintings of New York City. Curated by Barbara Haskell with the assistance of Sasha Nicholas, the exhibition debuted at the Whitney Museum of American Art from June 30 to October 16, 2011, and subsequently traveled to The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, January 16 – May 13, 2012.

Born and raised in New York City, Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956) moved at the age of sixteen to Germany to study music. Instead, he became a caricaturist and eventually a leading member of the German Expressionist groups Die Brücke and Die Blaue Reiter and, later, the Bauhaus. In the late 1930s, when the Nazi campaign against modern art necessitated his return to New York after an absence of fifty years, his marriage of abstraction and recognizable imagery made him a beloved artist in the United States.

Having spent fifty years of his life in Germany, Feininger is most often considered a German artist. This exhibition and its accompanying catalogue illuminate his dual national loyalties and their reverberations in his art. As Haskell notes in her catalogue essay: “(Feininger’s) complex and contradictory allegiances—to American ingenuity and lack of pretension on the one hand, and to German respect for tradition and learning on the other—rendered him an outsider in both countries. Always yearning for one world while living in the other, he never stopped longing for the ‘lost happiness’ of his childhood.”

Lyonel Feininger, "The Kin-der-Kids," from The Chicago Sunday Tribune, April 29, 1906, Commercial lithograph, 23 3/8 x 17 13/16 in. (59.4 x 45.3 cm), The Museum of Modern Art, New York; gift of the artist 260.1944.1 © 2011 Lyonel Feininger Family, LLC./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photograph © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Before he began to paint in 1907, at the age of thirty-six, Feininger had built a career as one of Germany's most successful caricaturists.

Newspaper Readers (1909)

When he turned to painting, he fused the whimsical figuration of his comic strips and illustrations with the high-keyed color of German Expressionist painting.

The Green Bridge

Just at the moment that Feininger's oils began to earn him widespread recognition, World War I broke out.

Self Portrait

He spent the war in Germany as an enemy alien, never having relinquished his American citizenship. In 1919, Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus, appointed Feininger as the school's first professor and commissioned him to design the cover of the Bauhaus manifesto. Feininger's expressionist woodcut, depicting a tripartite cathedral surrounded by shooting stars, symbolized the school's idealistic unification of fine art, architecture, and crafts.

Feininger remained at the Bauhaus until it was closed by the Nazis in 1933, revered as a teacher and head of the school's graphics workshop. The monumental compositions of architectural and seascape subjects that he produced at the Bauhaus gained him national renown, culminating in his receipt in 1931 of Germany's highest honor for an artist: a large-scale retrospective at Berlin's National Gallery.

Lyonel Feininger. Gelmeroda XIII (Gelmeroda), 1936 Oil on canvas, 39 1/2 x 31 5/8 in. (100.3 x 80.3 cm.) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; George A. Hearn Fund, 1942 42.158 © 2011 Lyonel Feininger Family, LLC./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photograph © The Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, NY

When the Nazi Party came to power in 1933, the situation became unbearable for Feininger and his wife, who was Jewish. They moved to America in 1937, just months before his work was featured in the Nazi's infamous Degenerate Art exhibition. Readjusting to the changed landscape of New York was difficult after such a long absence; not until 1939 did Feininger begin painting again. In America, as in Germany, he employed geometric forms to invest the modern world with a secular spirituality. Art, for him, was a "path to the intangibly Divine,” a way of expressing what he called the “glory there is in Creation." At the same time, Feininger continued in his last years to call upon the playful figurative vocabulary of his early illustrations and comics to evoke the harmony and innocence of childhood. Feininger's 1944 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, which traveled for two years to major American cities, established him as a major artist in his native country during his final years.

Nice article

The Book

A monograph accompanying the exhibition, with its overview essay by Whitney curator Barbara Haskell, covers the full breadth of Feininger’s career, placing his biography and art within the context of art history and politics, tracing his relationships to movements and institutions that defined the development of modern art, including Cubism, the Blaue Reiter, the Blue Four, the Bauhaus, and Black Mountain College. The catalogue features additional essays by Ulrich Luckhardt, curator, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Germany; Sasha Nicholas, senior curatorial assistant, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Bryan Gilliam, Frances Hill Fox Professor in Humanities, Duke University; John Carlin, independent writer and curator, president and CEO of Funny Garbage. The book is published by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, in association with Yale University Press, New Haven and London.

Wednesday, July 18, 2012

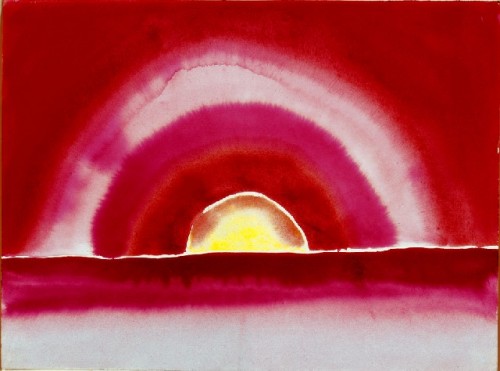

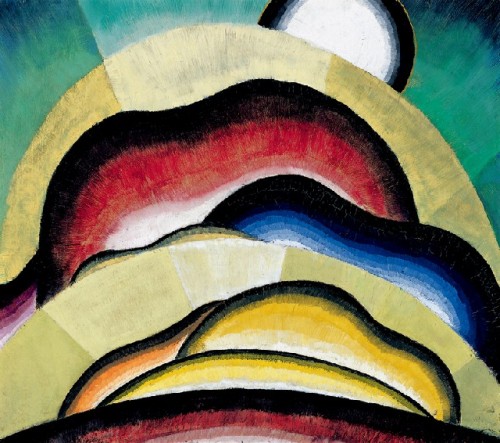

Dove/O’Keeffe: Circles of Influence

The life and work of Georgia O’Keeffe have fascinated critics, scholars, and art lovers alike since she burst onto the New York art scene in the early 1900s. On June 7, 2009 through September 7, 2009, the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute added a chapter to this story with the first exhibition to explore the role of the influential American modernist painter Arthur Dove as the key figure in O’Keeffe’s development of abstraction as a means of artistic expression. Dove/O’Keeffe: Circles of Influence featured 60 major oil paintings, watercolors, drawings, and pastels created from 1910 to the early 1940s. The Clark was the exclusive venue for this exhibition.

Among the seminal works on view were O’Keeffe’s Dark Abstraction (1924)

and Jack-in-The Pulpit No. VI (1930),

and Dove’s Moon (1935)

and Fog Horns (1929).

Although Dove and O’Keeffe’s approach to imagery ultimately diverged, their shared interest in capturing the ephemeral, fugitive traits of nature—the play of light on water, the transitions of the sun and moon, and the rustle of the wind through grass—was the basis for an abiding commitment to each other’s works and a profound aesthetic connection that lasted throughout their lifetimes.

“Georgia O’Keeffe has captured the imagination of art lovers around the world, not only by virtue of her incredible talent, but through her bohemian spirit as well,” said Clark director Michael Conforti. “The Clark is excited to look for the first time at O’Keeffe’s early modernist work along with the work of the extraordinary artist Arthur Dove, examining their shared influence on each other’s works.”

From the start of her career, O’Keeffe credited a reproduction of a Dove pastel as her introduction to modernism. Dove’s use of sensual, abstract forms to evoke the flowing rhythms and patterns of nature had already put him at the forefront of the American modernist movement by the time O’Keeffe entered the scene around 1916. Dove had been featured at the renowned photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s New York gallery “291” in 1912, and O’Keeffe’s work was first shown there in 1916. Works from this period, including Dove’s Abstraction, No. 3 (1910-11) and O’Keeffe’s No. 24-Special/No. 24 (1916-17), established the innovative aesthetic vision that characterized their early work.

During the 1920s and 1930s, critics began to take serious note of the two artists as major American modernist painters. In particular, the critics began to read the paintings from a Freudian point of view, pairing Dove and O’Keeffe as representative of the “masculine” and “feminine.” Unlike Dove, O’Keeffe reacted strongly against these psychoanalytic readings of her work, arguing for a more formal interpretation. Dove, always a strong and vocal supporter of O’Keeffe, ultimately used the Freudian interpretation in defense of O’Keeffe’s work.

O’Keeffe’s influence on Dove can be seen in the 1930s, when he turned to her early works, particularly her watercolors, such as Sunrise (1916), as means through which to renew his own work and vision.

Although O’Keeffe had long abandoned the medium, Dove created a number of important works including Sunrise #1 (1936) during this period, when he found his inspiration in what he called O’Keeffe’s “burning watercolors.”

The paintings from the exhibition will be drawn from international public and private collections. The exhibition featured works once owned by Alfred Stieglitz, O’Keeffe’s husband and Dove’s longtime friend, as well as works from the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. This exhibition was funded in part by the National Endowment for the Arts and by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

The exhibition was organized by the Clark and was curated by Debra Bricker Balken, an independent curator specializing in American modernism and contemporary art who organized a Dove retrospective in 1997.

More images from the exhibit:

Arthur Dove, Sunrise, 1924. Oil on panel, 18 1/4 x 20 7/8 in. Milwaukee Art Museum. Gift of Mrs. Edward R. Wehr [Milwaukee Art Museum (photo by John R. Glembin); Courtesy of and copyright The Estate of Arthur Dove / Courtesy Terry Dintenfass, Inc.]

Georgia O’Keeffe, Blue I, 1916. Watercolor on paper, 30 7/8 x 22 1/4 in. Private collection [(c) 2009 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York]

Georgia O’Keeffe, Red & Orange Streak, 1919. Oil on canvas, 27 x 23 in. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Bequest of Georgia O’Keeffe for the Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1987 [Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art]

More Images Here

The Clark published an exhibition catalogue authored by Balken and distributed by Yale University Press. This will be the first publication to focus on the relationship between Dove and O’Keeffe and explores the nature of art criticism in the early twentieth century as it related to psychoanalytic thought and formalism.

The Clark

Set amidst 140 acres in the Berkshires, the Clark is one of the few major art museums that also serves as a leading international center for research and scholarship. In addition to its extraordinary collections, the Clark organizes groundbreaking exhibitions that advance new scholarship and presents public and educational programs. The Clark’s research and academic programs include an international fellowship program and conferences. The Clark, together with Williams College, sponsors one of the nation’s leading master’s programs in art history.

In June 2008, the Clark opened Stone Hill Center, the first phase of its expansion and campus enhancement project. Designed by Tadao Ando, the 32,000-square-foot, wood-and-glass building houses two galleries, a meeting and studio art classroom, an outdoor café, and the Williamstown Art Conservation Center. The second phase of the expansion includes the creation of another stand-alone building by Ando that will house exhibition galleries, visitor services, and education and conference spaces. Scheduled for completion in 2013, Phase II also encompasses the upgrade and internal expansion of the Clark’s current buildings by Annabelle Selldorf.

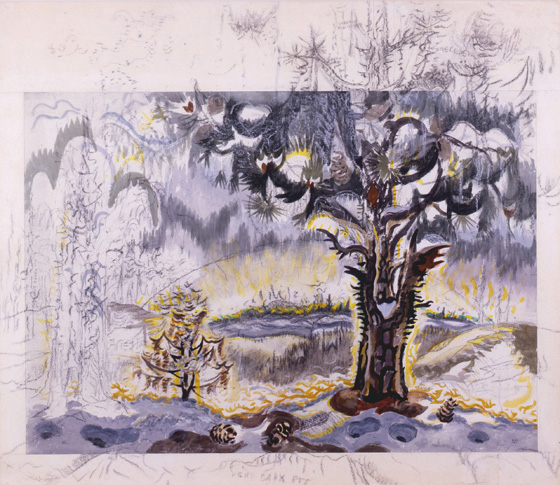

The Paintings of Charles Burchfield

The Whitney Museum of American Art focused on the work of the visionary artist Charles Burchfield (1893-1967) in an exhibition curated by acclaimed sculptor Robert Gober. Heat Waves in a Swamp: The Paintings of Charles Burchfield, on view from June 24 through October 17, 2010, featured more than one hundred watercolors, drawings, and paintings from private and public collections, as well as selections from Burchfield’s journals, sketches, scrapbooks, and correspondence. Organized by the Hammer Museum, in collaboration with the Burchfield Penney Art Center in Buffalo, the exhibition provided the most comprehensive examination to date of an underappreciated modernist master.

Charles Burchfield, An April Mood, 1946–55. Watercolor and charcoal on joined paper, 40 × 54 in. (101.6 × 137.2 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York

Born in 1893 in Ashtabula Harbor, Ohio, and raised nearby in Salem, Burchfield spent most of his adult life in upstate New York, in Buffalo, where he moved in 1921, and the neighboring suburb of Gardenville. Working almost exclusively in watercolor on paper, his principal subject was his experience of the natural world, which led him to create deeply personal landscapes that are often imbued with highly expressionistic light.

His works quiver with color and the almost audible sounds of humming insects, rustling leaves, bells, birds, and vibrating telephone lines. In 1945 he noted, “It is as difficult to take in all the glory of a dandelion, as it is to take in a mountain, or a thunderstorm.”

Contemporary artist Robert Gober has curated previous exhibitions, most notably The Meat Wagon at the Menil Collection in Houston, in 2005, drawn from the diverse selection of works in the Menil’s holdings. With this exhibition, Gober – who discovered that his interest in Burchfield was shared by Hammer Director Ann Philbin and coordinating curator/Hammer Deputy Director Cynthia Burlingham – was for the first time curating a large-scale monographic show of another artist’s work. The exhibition is arranged chronologically, with each room presenting a distinct phase of Burchfield’s career. Exploring both physical and psychological terrain, Gober has augmented the selection of Burchfield’s works with extensive material that sheds light on the artist’s thoughts about his work and artistic practice. Burchfield (with much help from his wife, Bertha) left a trove of well-maintained sketches, jottings, notebooks, journals, and ephemera spanning his entire career. This material is now part of the Burchfield Penney Art Center at Buffalo State College.

The title of the show, Heat Waves in a Swamp, came from the title of a Burchfield watercolor. Gober writes of Burchfield in his catalogue introduction: “He loved swamps and bogs and marshes. He loved all of nature and was torn as a young man between being an artist and being a nature writer. He liked nothing more than to paint while literally standing in a swamp. Liked the mosquitoes and the rain and the decay of vegetation. I felt early on that this title had a metaphorical sweep that captured Burchfield’s enthusiasms at their deepest and best.”

The exhibition began with work Burchfield created in 1916 while living in Salem, Ohio, and follows his career with particular attention to transformative and reflective moments in his life and work. Among the earliest works is a 1917 sketchbook entitled “Conventions for Abstract Thoughts,” which includes a series of symbolic drawings depicting human emotions. The abstract forms in these drawings would reappear in Burchfield’s work for years to come.

Dawn of Spring

A room was dedicated to a series of works that were shown in a 1930 exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art, Charles Burchfield: Early Watercolors, 1916 to 1918, the first show at MoMA devoted to a single artist. Correspondence between Burchfield and MoMA’s legendary curator/director Alfred Barr will be shown alongside the work. As Gober noted, “Burchfield’s complex communion with nature, as seen in these early watercolors, would resurface later, becoming the inspirational touchstone for the work of the last two decades of his life.”

From 1921 to 1929 Burchfield worked as a designer at the M. H. Birge & Sons wallpaper factory in Buffalo. His designs, like all his art, were based in nature and reveal such diverse influences as Japanese woodcuts by Katsushika Hokusai and Ando Hiroshige, Chinese scroll paintings, and the illustrations of Arthur Rackham. Burchfield’s work as a wallpaper designer during the 1920s is featured in a room that includes watercolors from the same period hanging on walls covered in a reprint of one of his designs. When the opportunity arose to show his paintings at the Frank K. M. Rehn Galleries in New York, Burchfield gave up his job and decided to paint full time.

Burchfield accepted commissions from Fortune magazine to paint railroads in Pennsylvania, sulphur mines in Texas, and coal mines in Virginia. Many of his paintings of this period deal with the rural and industrial worlds around him and present these worlds in a less fantastical way than in his earlier watercolors. By the mid-1930s, Burchfield was celebrated for his realist depictions of the American landscape.

In 1943 Burchfield faced a creative crisis as he was approaching fifty and the country was in the middle of World War II. At that point he began to look back at his earlier watercolors and to expand them. The exhibition reunites two pivotal paintings, both completed in 1943 within a month of each other, although one was begun in 1917 and the other in 1934. These two paintings, The Coming of Spring and Two Ravines, were the works that marked Burchfield’s transition from crisis to the extraordinary achievements of his last two decades. Gober notes, “He felt that his work had lost the intensity of his early watercolors, and in his struggle to make works that he felt reflected the best possibilities for his creativity, he took early drawings and physically expanded them to make these two landmark works.”

Although he struggled with health problems during the 1950s and 60s, until his death in 1967, Burchfield created some of his most vibrant and fascinating works toward the end of his life. As Gober writes, “The works from this period of Burchfield’s life are immersed in what he perceived as the complicated beauty and spirituality of nature and are often imbued with visionary, apocalyptic, and hallucinatory qualities. In these large, late watercolors, Burchfield was able to execute with grace and beauty many of the painting ideas that he had developed as a young man…And in so doing, he transformed himself and his practice, producing one of the rarest events in the life of any artist: great art in old age.”

Lots more images - must see

Catalogue

The exhibition was accompanied by a catalogue edited by Cynthia Burlingham and Robert Gober, with an introduction by Gober and essays by Burlingham and Gober, as well as by critic Dave Hickey; Burchfield Penney Art Center Charles Cary Rumsey Curator Nancy Weekly; and Burchfield Penney Art Center Research Assistant Tullis Johnson. It was published by the Hammer Museum and DelMonico Books, an imprint of Prestel Publishing.

Tuesday, July 17, 2012

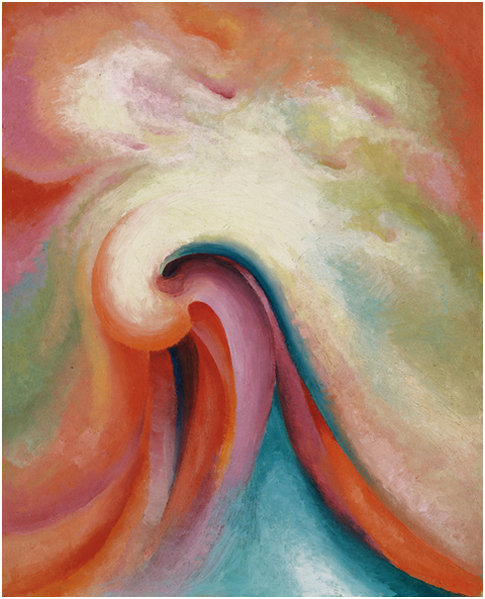

Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction

The artistic achievement of Georgia O’Keeffe was examined from a fresh perspective in Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction, a landmark exhibition debuting this fall at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

While O’Keeffe (1887–1986) has long been recognized as one of the central figures in 20th-century art, the radical abstract work she created throughout her long career has remained less well-known than her representational art.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Blue Flower, 1918. Pastel on paper mounted on cardboard, 20 × 16 in. (50.8 × 40.6 cm). Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico; gift of The Burnett Foundation. © Private collection

By surveying her abstractions, Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction, repositioned O’Keeffe as one of America's first and most daring abstract artists. The exhibition was on view in the Whitney’s third-floor Peter Norton Family Galleries from September 17, 2009 through January 17, 2010.

Including more than 130 paintings, drawings, watercolors, and sculptures by O'Keeffe as well as selected examples of Alfred Stieglitz’s famous photographic portrait series of O’Keeffe, the exhibition had been many years in the making.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Untitled (Abstraction/Portrait of Paul Strand), 1917

The curatorial team, led by Whitney curator Barbara Haskell, included Barbara Buhler Lynes, the curator of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum and the Emily Fisher Landau Director of the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum Research Center; Bruce Robertson, professor of the history of art and architecture at the University of California, Santa Barbara; Elizabeth Hutton Turner, professor and vice provost for the arts at the University of Virginia and guest curator at The Phillips Collection; and Sasha Nicholas, Whitney curatorial assistant.

The exhibition was accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue with essays by the organizers, selections from the recently unsealed Stieglitz-O’Keeffe correspondence, and a contextual chronology of O’Keeffe’s life and work.

"Series I, No. 8," 1919, by Georgia O'Keeffe. Photo: Georgia O'Keeffe Museum/Artist Rights Society, New York

Following its Whitney debut, the show traveled to The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C., February 6-May 9, 2010, and to the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, May 28- September 12, 2010.

"Series I-No. 3," 1918. Photo: Milwaukee Art Museum

While it is true that O’Keeffe has entered the public imagination as a painter of sensual, feminine subjects, she is nevertheless viewed first and foremost as a painter of places and things. When one thinks of her work it is usually of her magnified images of open flowers and her iconic depictions of animal bones, her Lake George landscapes, her images of stark New Mexican cliffs, and her still lifes of fruit, leaves, shells, rocks, and bones. Even O’Keeffe’s canvasses of architecture, from the skyscrapers of Manhattan to the adobe structures of Abiquiu, come to mind more readily than the numerous works—made throughout her career—that she termed abstract.

From the Lake, 1924

This exhibition was the first to examine O'Keeffe's achievement as an abstract artist. In 1915, O'Keeffe leaped into the forefront of American modernism with a group of abstract charcoal drawings that were among the most radical creations produced in the United States at that time. A year later, she added color to her repertoire; by 1918, she was expressing the union of abstract form and color in paint.

Georgia O’Keeffe Flower Abstraction, 1924 Oil on canvas, 48 x 30 in. (121.9 x 76.2 cm) Whitney Museum of American Art, New York 50th Anniversary Gift of Sandra Payson 85.47 Copyright Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York

First exhibited in 1923, O’Keeffe’s psychologically charged, brilliantly colored abstract oils garnered immediate critical and public acclaim. For the next decade, abstraction would dominate her attention. Even after 1930, when O’Keeffe’s focus turned increasingly to representational subjects, she never abandoned abstraction, which remained the guiding principle of her art. She returned to abstraction in the mid-1940s with a new, planar vocabulary that provided a precedent for a younger generation of abstractionists.

Early Abstraction, 1915 Abstraction and representation for O’Keeffe were neither binary nor oppositional. She moved freely from one to the other, cognizant that all art is rooted in an underlying abstract formal invention. For O’Keeffe, abstraction offered a way to communicate ineffable thoughts and sensations. As she said in 1976, “The abstraction is often the most definite form for the intangible thing in myself that I can only clarify in paint.” Through her personal language of abstraction, she sought to give visual form (as she confided in a 1916 letter to Alfred Stieglitz) to “things I feel and want to say - [but] havent [sic] words for.” Abstraction allowed her to express intangible experience—be it a quality of light, color, sound, or response to a person or place. As O’Keeffe defined it in 1923, her goal as a painter was to “make the unknown—known. By unknown I mean the thing that means so much to the person that he wants to put it down—clarify something he feels but does not clearly understand.”

Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, 1918

This exhibition and catalogue chronicled the trajectory of O'Keeffe's career as an abstract artist and examine the forces impacting the changes in her subject matter and style. From the beginning of her career, she was, as critic Henry McBride remarked, “a newspaper personality.” Interpretations of her art were shaped almost exclusively by Alfred Stieglitz, artist, charismatic impresario, dealer, editor, and O’Keeffe’s eventual husband, who presented her work from 1916 to 1946 at the groundbreaking galleries “291”, the Anderson Galleries, the Intimate Gallery, and An American Place. Stieglitz’s public and private statements about O’Keeffe’s early abstractions and the photographs he took of her, partially clothed or nude, led critics to interpret her work—to her great dismay—as Freudian-tinged, psychological expressions of her sexuality.

Abstraction Blue

Cognizant of the public’s lack of sympathy for abstraction and seeking to direct the critics away from sexualized readings of her work, O’Keeffe self-consciously began to introduce more recognizable images into her repertoire in the mid-1920s. As she wrote to the writer Sherwood Anderson in 1924, “I suppose the reason I got down to an effort to be objective is that I didn’t like the interpretations of my other things [abstractions].” O’Keeffe’s increasing shift to representational subjects, coupled with Stieglitz’s penchant for favoring the exhibition of new, previously unseen work, meant that O’Keeffe’s abstractions rarely figured in the exhibitions Stieglitz mounted of her work after 1930, with the result that her first forays into abstraction virtually disappeared from public view.

Catalogue

In addition to rethinking O'Keeffe's place in American modernism, the book that accompanied this exhibition reappraises the origin and singular character of her abstract vocabulary and the stylistic shifts which her art underwent over the span of her long career. It adds significant new insight into her art and life, publishing for the first time excerpts of recently unsealed letters written by O’Keeffe to photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, whom she married in 1924. These letters, along with a contextual chronology and other primary documents referenced by the authors, offer an intimate glimpse into her creative method and intentions as an artist. Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction, was organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC; and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, NM.

Nice review, more images

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)