Watts Contemporary Gallery

26th June to November 26 2017

George Frederic Watts (1817-1904) was one of the most

original artists of the nineteenth century. An accomplished painter,

sculptor, draughtsman and creator of vast murals, he became known in his

own time as 'England's Michelangelo'. The term suggests an artist of

range, depth and intensity.

Born in London, Watts was a highly ambitious young man, and he spent several years in Italy during the 1840s studying the art of the Renaissance. For the rest of his long career, he aimed to emulate both the magnificent forms of Classical Antiquity and the sumptuous colours of the Italian masters.

At the same time, Watts strongly felt that art had the capacity to change people's lives in modern Britain, and that his own work might have an important role in helping society move forwards. Fundamentally, he believed that his message of hope, progress and evolution was relevant to everyone.

Early in his career, the artist responded to press reports about the plight of the poor by painting angry scenes of realism such as

Found Drowned (c. 1848-50, Watts Gallery Trust).

He also sought to place his pictures where they might have an impact beyond the art-world:

The Good Samaritan (1850, Manchester Art Gallery), for example, was presented to Manchester Town Hall in honor of a local prison reformer, while a mosaic version of

Time, Death and Judgement (late 1870s-1896, St Paul's Cathedral) was placed on public view in London's East End. Over time, Watts came to be seen as a type of painter-prophet.

As well as commenting on the state of society through the medium of his art, Watts often reinterpreted stories from the past so that they might speak to those in the present, as in his

Eve triptych (from 1868, Watts Gallery Trust and Tate),

The Death of Cain (c. 1872-75, Royal Academy of Arts)

and Prometheus (1857-1904, Watts Gallery Trust).

Yet perhaps his most powerful symbolic works are strikingly bold, cosmic visions such as

Hope (1886, Private Collection)

The All-Pervading (1887-96, Tate)

and The Sower of the Systems (1902, Art Gallery of Ontario).

By giving human form to universal — for instance in

Love and Life (1884, Private Collection)

or Love and Death (c. 1874-87, The Whitworth Art Gallery)

— he hoped to make them more relatable. Taken together, this avant-garde imagery reveals the artist's enduring quest to find a visual language to express his sense of human progress being bound up in the unfolding of the universe.

It was through portraiture that Watts was able to capture the spirit of his times. From youth into old age, the artist painted likenesses of himself, his friends and his famous contemporaries. Upheld as portraitist to the nation, he invited influential figures – including the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne, the artist Frederic Leighton and the Catholic leader Cardinal Manning – to join his illustrious Hall of Fame.

Equally as compelling are his portraits of women, such as his charismatic first wife, the great actress Ellen Terry, the authoress Marie Fox (Princess Liechtenstein), and Jeanie Senior — Britain's first female civil servant — whose pioneering social reforms inspired the artist to make use of his own celebrity to support philanthropic causes. Eventually it was said that 'the world begged' to sit for Watts.

G F Watts: England's Michelangelo brings together many of Watts's most celebrated works including his cosmic imagery, protest paintings and dramatic portraits. See this unique one-off exhibition at Watts Gallery until 26 November.

P.S.

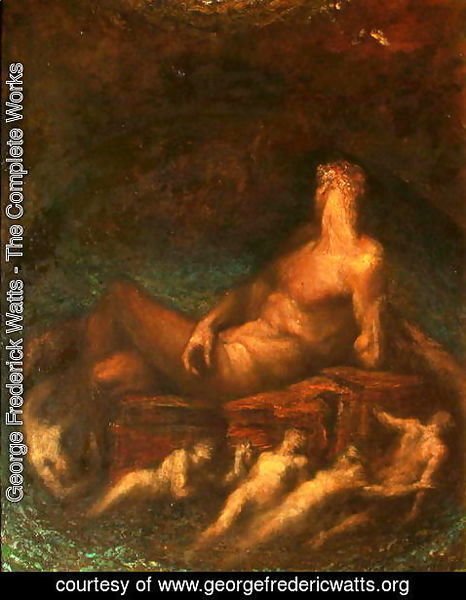

July 13, 2017 Sotheby offered one of the greatest compositions by George Frederic Watts, ‘England’s Michelangelo’, to come to auction. A tour de force of dramatic power,

Orpheus and Eurydice remained in Watts’ possession until his death in 1904 when it was inherited by his adopted daughter Lilian. The romantic subject matter may have been inspired by the emotions Watts was experiencing following the breakdown of his first marriage to the young actress Ellen Terry, resulting in their separation after only eleven months. The painting was offered at Sotheby’s London sale of Victorian, Pre-Raphaelite & British Impressionist Art on 13 July with an estimate of £300,000-500,000.

Simon Toll, Sotheby’s Victorian Art Specialist, said: “Orpheus and Eurydice encapsulates everything that made Watts’ art so visionary and revolutionary in the 1860s – powerful drama, a sensual and expressive use of paint and rich colour and reverence for the work of the Italian Old Masters. This hauntingly beautiful vision of lost love is among a handful of his best-known pictures and the most important example of his art to be seen at auction in the last decade and a half. It is fitting that a picture of two lovers emerging from the shadows should itself re- emerge into public view in the year that marks the two-hundred year anniversary of the artist’s birth.”

The legend of Orpheus and Eurydice was popular in the 1860s at a time of revival for classical subject matter in British art. Rossetti, Burne-Jones, and Watts’ neighbour in Kensington, Leighton, produced their own visual interpretations of the moment when Orpheus, after journeying to the Underworld to lead Eurydice back to Earth, gives in to temptation to look at his wife despite the warning not to look back at her until they reached daylight. Watts was fascinated by the subject and made at least eight paintings of the two lovers, the earliest version in 1869, towards the end of a decade in which he had immersed himself in themes of abandonment, romantic disappointment and separation. The version to be offered for sale is probably the culmination of the artist’s experiments with a horizontal format and half-length figures, painted circa 1870. After 1872, he used a vertical format of full-length figures, which arguably lessens the intimacy and intensity of the composition. Watts never ceased to be fascinated by the possibilities of the narrative and in the last years of his life he painted another version.

Such an important picture in Watts’ oeuvre, Orpheus and Eurydice required a large number of sketches and drawings, a process in which he worked through the dynamic controposto of the figures, especially the stretch and turn of their necks. Whilst aspects of the painting echo the traditions of the Renaissance, particularly the colouring of Titian, others are wholly modern and anticipate the abstractions of the next century. A significant tenet of the new Classicism that emerged in the 1860s was that narrative should be conveyed by the artistic qualities of gesture, form and colour rather than in details and accessories requiring interpretation. In this version of the work, Orpheus is clothed in a swirling vortex of fiery red drapery, suggestive of the flames of his father Apollo the Sun-God, his tanned muscular body contrasting with the languid pallor of Eurydice. The insertion of a dead tree-trunk marks the boundary between the worlds of life and death, a device which heightens the heart-breaking moment when Orpheus turns to see his wife disappear into the darkness forever.

Orpheus and Eurydice demonstrates the stylistic preoccupations of the new art movement of the 1860s, when fifth century Greek art was considered the fountainhead of beauty. Combining grandeur with naturalness, Phidias’ sculptures for the Parthenon were regarded as the most important treasures of the ancient world. The figures in the painting reveal close study of the Parthenon pediment figures in their drapery and anatomy.

One of the most remarkable men of the nineteenth century, Watts is perhaps now best-known for his magnificent sculpture

Physical Energy in Kensington Gardens and for his large, imposing mythological, biblical and symbolist canvases. He also portrayed every great statesman, artist, poet, aristocrat and society beauty of his generation. Genuinely interested in the great issues of the day, he challenged the injustices of the world in his allegorical paintings. The most famous of all Watts’ paintings is

Hope, a postcard of which Nelson Mandela kept in his prison-cell at Robin Island.

Born in London, Watts was a highly ambitious young man, and he spent several years in Italy during the 1840s studying the art of the Renaissance. For the rest of his long career, he aimed to emulate both the magnificent forms of Classical Antiquity and the sumptuous colours of the Italian masters.

At the same time, Watts strongly felt that art had the capacity to change people's lives in modern Britain, and that his own work might have an important role in helping society move forwards. Fundamentally, he believed that his message of hope, progress and evolution was relevant to everyone.

Early in his career, the artist responded to press reports about the plight of the poor by painting angry scenes of realism such as

Found Drowned (c. 1848-50, Watts Gallery Trust).

He also sought to place his pictures where they might have an impact beyond the art-world:

The Good Samaritan (1850, Manchester Art Gallery), for example, was presented to Manchester Town Hall in honor of a local prison reformer, while a mosaic version of

Time, Death and Judgement (late 1870s-1896, St Paul's Cathedral) was placed on public view in London's East End. Over time, Watts came to be seen as a type of painter-prophet.

As well as commenting on the state of society through the medium of his art, Watts often reinterpreted stories from the past so that they might speak to those in the present, as in his

Eve triptych (from 1868, Watts Gallery Trust and Tate),

The Death of Cain (c. 1872-75, Royal Academy of Arts)

and Prometheus (1857-1904, Watts Gallery Trust).

Yet perhaps his most powerful symbolic works are strikingly bold, cosmic visions such as

Hope (1886, Private Collection)

The All-Pervading (1887-96, Tate)

and The Sower of the Systems (1902, Art Gallery of Ontario).

By giving human form to universal — for instance in

Love and Life (1884, Private Collection)

or Love and Death (c. 1874-87, The Whitworth Art Gallery)

— he hoped to make them more relatable. Taken together, this avant-garde imagery reveals the artist's enduring quest to find a visual language to express his sense of human progress being bound up in the unfolding of the universe.

It was through portraiture that Watts was able to capture the spirit of his times. From youth into old age, the artist painted likenesses of himself, his friends and his famous contemporaries. Upheld as portraitist to the nation, he invited influential figures – including the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne, the artist Frederic Leighton and the Catholic leader Cardinal Manning – to join his illustrious Hall of Fame.

Equally as compelling are his portraits of women, such as his charismatic first wife, the great actress Ellen Terry, the authoress Marie Fox (Princess Liechtenstein), and Jeanie Senior — Britain's first female civil servant — whose pioneering social reforms inspired the artist to make use of his own celebrity to support philanthropic causes. Eventually it was said that 'the world begged' to sit for Watts.

G F Watts: England's Michelangelo brings together many of Watts's most celebrated works including his cosmic imagery, protest paintings and dramatic portraits. See this unique one-off exhibition at Watts Gallery until 26 November.

P.S.

July 13, 2017 Sotheby offered one of the greatest compositions by George Frederic Watts, ‘England’s Michelangelo’, to come to auction. A tour de force of dramatic power,

Orpheus and Eurydice remained in Watts’ possession until his death in 1904 when it was inherited by his adopted daughter Lilian. The romantic subject matter may have been inspired by the emotions Watts was experiencing following the breakdown of his first marriage to the young actress Ellen Terry, resulting in their separation after only eleven months. The painting was offered at Sotheby’s London sale of Victorian, Pre-Raphaelite & British Impressionist Art on 13 July with an estimate of £300,000-500,000.

Simon Toll, Sotheby’s Victorian Art Specialist, said: “Orpheus and Eurydice encapsulates everything that made Watts’ art so visionary and revolutionary in the 1860s – powerful drama, a sensual and expressive use of paint and rich colour and reverence for the work of the Italian Old Masters. This hauntingly beautiful vision of lost love is among a handful of his best-known pictures and the most important example of his art to be seen at auction in the last decade and a half. It is fitting that a picture of two lovers emerging from the shadows should itself re- emerge into public view in the year that marks the two-hundred year anniversary of the artist’s birth.”

The legend of Orpheus and Eurydice was popular in the 1860s at a time of revival for classical subject matter in British art. Rossetti, Burne-Jones, and Watts’ neighbour in Kensington, Leighton, produced their own visual interpretations of the moment when Orpheus, after journeying to the Underworld to lead Eurydice back to Earth, gives in to temptation to look at his wife despite the warning not to look back at her until they reached daylight. Watts was fascinated by the subject and made at least eight paintings of the two lovers, the earliest version in 1869, towards the end of a decade in which he had immersed himself in themes of abandonment, romantic disappointment and separation. The version to be offered for sale is probably the culmination of the artist’s experiments with a horizontal format and half-length figures, painted circa 1870. After 1872, he used a vertical format of full-length figures, which arguably lessens the intimacy and intensity of the composition. Watts never ceased to be fascinated by the possibilities of the narrative and in the last years of his life he painted another version.

Such an important picture in Watts’ oeuvre, Orpheus and Eurydice required a large number of sketches and drawings, a process in which he worked through the dynamic controposto of the figures, especially the stretch and turn of their necks. Whilst aspects of the painting echo the traditions of the Renaissance, particularly the colouring of Titian, others are wholly modern and anticipate the abstractions of the next century. A significant tenet of the new Classicism that emerged in the 1860s was that narrative should be conveyed by the artistic qualities of gesture, form and colour rather than in details and accessories requiring interpretation. In this version of the work, Orpheus is clothed in a swirling vortex of fiery red drapery, suggestive of the flames of his father Apollo the Sun-God, his tanned muscular body contrasting with the languid pallor of Eurydice. The insertion of a dead tree-trunk marks the boundary between the worlds of life and death, a device which heightens the heart-breaking moment when Orpheus turns to see his wife disappear into the darkness forever.

Orpheus and Eurydice demonstrates the stylistic preoccupations of the new art movement of the 1860s, when fifth century Greek art was considered the fountainhead of beauty. Combining grandeur with naturalness, Phidias’ sculptures for the Parthenon were regarded as the most important treasures of the ancient world. The figures in the painting reveal close study of the Parthenon pediment figures in their drapery and anatomy.

One of the most remarkable men of the nineteenth century, Watts is perhaps now best-known for his magnificent sculpture

Physical Energy in Kensington Gardens and for his large, imposing mythological, biblical and symbolist canvases. He also portrayed every great statesman, artist, poet, aristocrat and society beauty of his generation. Genuinely interested in the great issues of the day, he challenged the injustices of the world in his allegorical paintings. The most famous of all Watts’ paintings is

Hope, a postcard of which Nelson Mandela kept in his prison-cell at Robin Island.