The Gallery, Winchester Discovery Centre

5 August – 15 October 2017,

5 August – 15 October 2017,

Sainsbury Gallery, Willis Museum,

Basingstoke

21 October – 16 December 2017,

In the weeks prior to his death, J.M.W. Turner is said to have declared (to John Ruskin) ‘The Sun is God’ – what

he meant by this, no-one really knows, but what is not in any doubt is

the central role that the sun played in Turner’s lifelong obsession with

light and how to paint it.

Turner and the Sun,

an exhibition curated by Hampshire Cultural Trust, will be the first

ever to be devoted solely to the artist’s lifelong obsession with the

sun. Whether it is the soft light of dawn, the uncompromising brilliance

of midday or the technicolour vibrancy of sunset, his light-drenched

landscapes bear testimony to the central role that the sun assumed in

Turner’s art. Through twelve generous loans from Tate Britain – the

majority of which are rarely on public display – this focused exhibition

will consider how the artist repeatedly explored the transformative

effects of sunlight and sought to capture its vivid hues in paint.The sun appears in many different guises in Turner’s work. Sometimes it is something very natural and elemental, at others it is more mysterious and mystical. Turner was working in an era when the sun - what it was, what it was made of and the source of its power - was still a source of mystery and wonder. The Royal Society was housed in the same building as the Royal Academy, and it is known that Turner attended lectures and was acquainted with scientists such as Faraday and Somerville. It is therefore possible that he was influenced by new scientific theories about the sun when he tried to depict it. Certainly, Turner’s own Eclipse Sketchbook of 1804 – which will be featured in the exhibition - shows him recording visual data of an atmospheric effect on the spot.

Turner also mined ancient mythology for inspiration. The tale of Regulus, the Roman general punished by having his eyelids cut off and thus made to stare at the sun, is echoed by the artist replicating the effect of solar glare in paint, while the stories of Apollo and the Python and Chryses both feature the Greek sun god, Apollo.

Given his place in the vanguard of Romanticism, Turner was also interested in poetry and wrote his own pastoral verse. He would often acclaim the life-giving energy of the sun and bemoan its absence during Winter: ‘The long-lost Sun below the horizon drawn, ‘Tis twilight dim no crimson blush of morn’ and ‘as wild Thyme sweet on sunny bank, that morn’s first ray delighted drank.’

Highlights of Turner and the Sun include

Sun Setting over a Lake (c 1840, Tate) an unfinished but highly vivid depiction of a sunset. At first, the viewer tries to discern behind what is, possibly, Lake Lucerne in Switzerland, but what soon becomes evident, is that the principal subject of the painting is the light and the way it is reflected in the water and gilds the sky and clouds above.

A charming example of Turner painting rays of sunlight emanating from the centre of the composition can be seen in

The Lake, Petworth, Sunset; Sample Study (c.1827-8, Tate), which is one of a series of six sample studies made for the four finished canvases for Petworth House.

Venice: The Giudecca Canal, Looking Towards Fusina at Sunset (1840, Tate)

The popularity of the Grand Tour and the enduring appeal of Venice created a lucrative and artistically important opportunity for Turner in his late career.

Going to the Ball (San Martino) , exhibited 1864, Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775 – 1851). Tate: Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856. Photo © Tate, London 2017.

In Going to the Ball (San Martino) (exhibited 1846, Tate), we see boats taking Venetian revellers to a masque ball against the backdrop of a golden cityscape. This was Turner’s last painting of Venice and was in his studio at the time of his death in 1851.

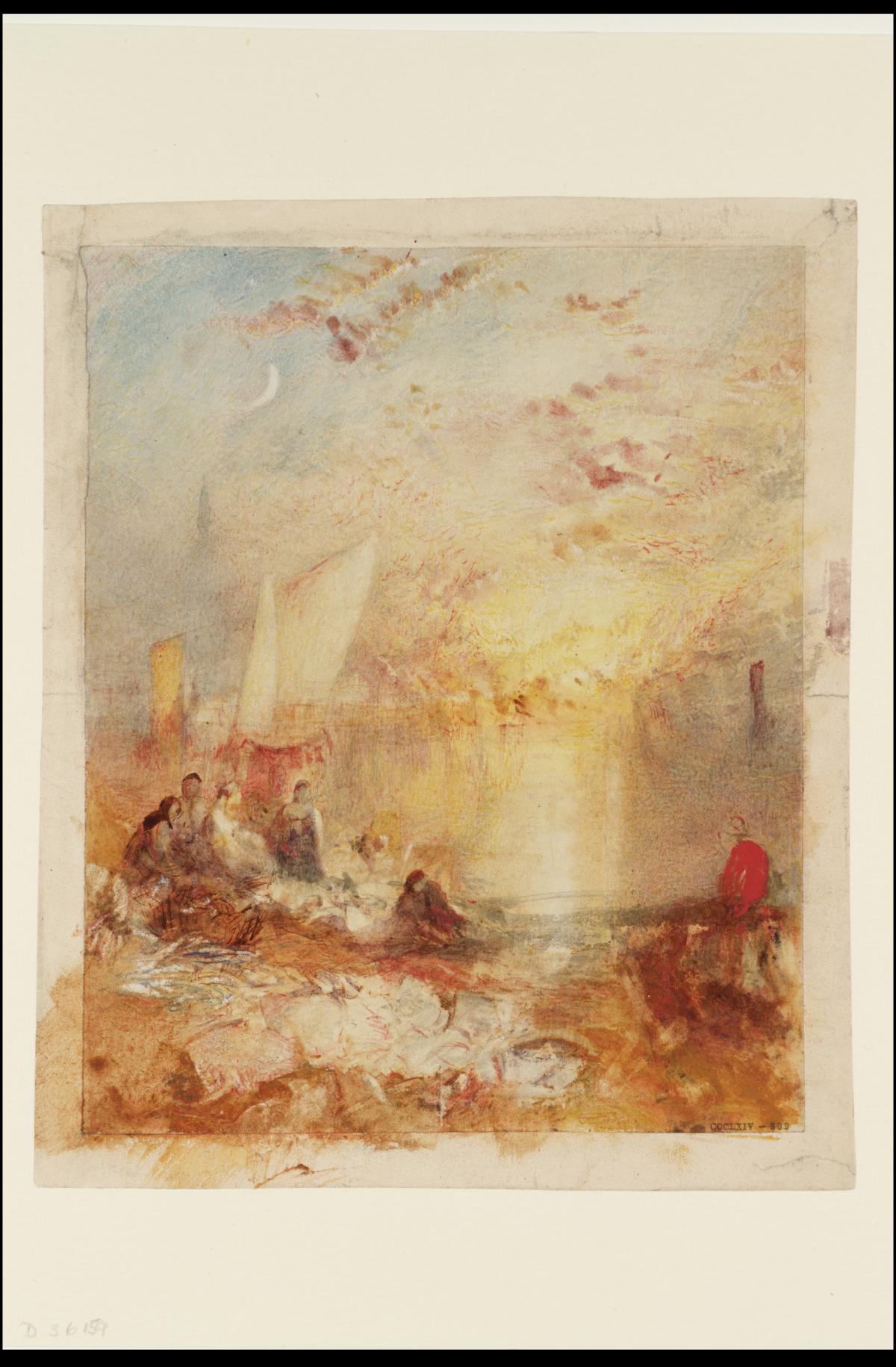

Sunset: A Fish Market on the Beach ,c.1835. Copyright Tate, London, 2015.

Some of Turner’s most acutely observed images of the sun are his informal, private exercises in watercolour and experiments with wash and colour. Swiftly executed, sometimes in batches, they capture transient effects where the sky is utterly dominated by the effects of the sun. A selection of these will be seen in the exhibition, and they are normally only viewed by appointment.

Exhibition curator Nicola Moorby said: “We all know that Turner is the great painter of the sun, but what is particularly interesting is trying to analyse why.”

She continues: “One of the reasons he is such an exciting and inspirational painter is because he has a very experimental approach to technique. In order to try and replicate the effects of the sun in paint, he uses a whole range of visual tricks and devices. For example, we often seen him juxtaposing the lightest area of a composition with something very dark to heighten the contrast. He uses arcs, orbs, radiating circles of colour, broken brushstrokes, textured oil paint, seamless watercolour wash – sometimes he depicts sunlight as something very solid and physical, at other times it is a dazzling glare that we can’t properly see. Turner doesn’t just try to paint the sun. He seems to want to actually try and replicate its energy and light so that it shines out of his pictures.”

Janet Owen, Chief Executive of Hampshire Cultural Trust, says: “By combining naturalistic observation with imaginative flights of fancy, Turner’s light-drenched landscapes encapsulate the elemental force of his art and remain as dazzling today as they were for a contemporary audience. We are thrilled to be able to shine a spotlight on them here in Hampshire.”