Monday, October 8, 2012

Diego Rivera: Murals for The Museum of Modern Art

The exhibition Diego Rivera: Murals for The Museum of Modern Art reunited, for the first time in 80 years, five “portable murals,” freestanding frescoes with bold images addressing the Mexican Revolution and Depression-era New York that Rivera created at the Museum for his 1931–32 MoMA exhibition. The exhibition was on view at MoMA from November 13, 2011, to May 14, 2012. The murals, which are up to six feet by eight feet in size and weigh as much as 1,000 pounds, are made of frescoed plaster, concrete, and steel. Comprising five of the eight murals that were shown in the 1931 exhibition, they were drawn from public and private collections in the United States and Mexico, including MoMA’s own collection. Diego Rivera: Murals for The Museum of Modern Art was organized by Leah Dickerman, Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture, The Museum of Modern Art. MoMA was the exhibition’s sole venue.

In addition to the murals, the exhibition featured three eight-foot working drawings; a prototype “portable mural” made in 1930; as well as smaller drawings, watercolors, and prints by Rivera. The exhibition also included materials related to Rivera’s infamous Rockefeller Center mural, a project he began to discuss while in residence at the Museum.

By 1931 Rivera was the most visible figure in Mexican muralism, a large-scale public-art initiative that emerged in the 1920s in the wake of the Mexican Revolution. But his murals—by definition fixed on a single site—were impossible to transport for exhibition. To solve this problem, the Museum brought Rivera to New York six weeks before the show opened and provided him with a makeshift studio in an empty gallery in the Museum’s original building. Working around the clock with three assistants, Rivera produced five “portable murals,” large blocks of frescoed plaster, concrete, and steel that feature bold images commemorating Mexican history. Four of these five panels featured images borrowed, with some adaptations, from the mural cycles in Mexico that had established Rivera’s reputation. At MoMA these images formed a new cycle: a series of historical snapshots of Mexican power relationships. Together they present the nation in a continual state of revolution—from the Spanish Conquest in the 16th century to labor unrest in the decade in which they were made.

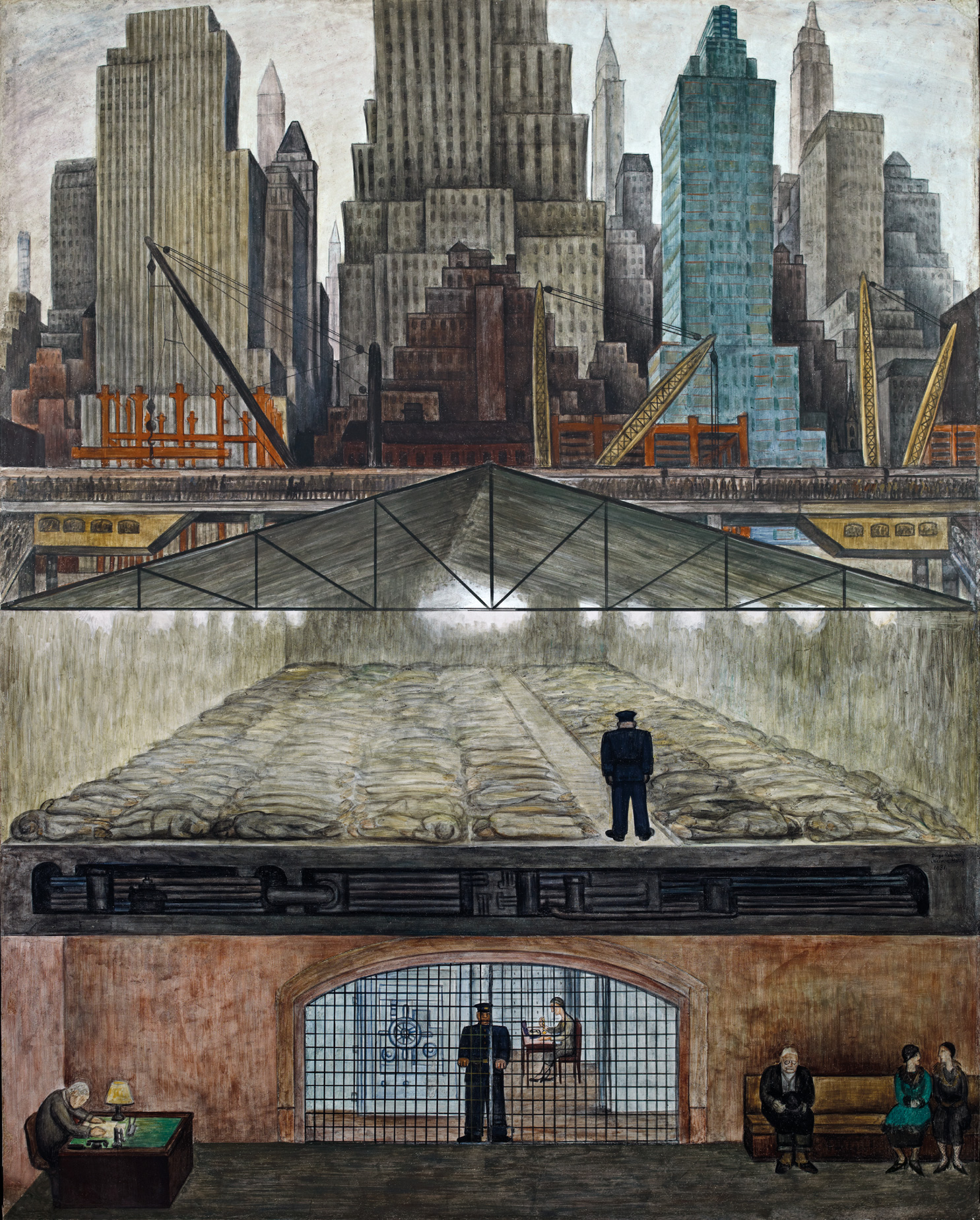

The first of these panels to be made, Agrarian Leader Zapata, later joined MoMA’s collection, and is now a familiar icon on the Museum’s walls. After the exhibition’s opening, Rivera added three more murals, each depicting labor and construction in Depression-era New York. The city’s advanced industrialization provided Rivera with exciting modern subjects for his murals, while its economic inequities offered ample opportunity to scrutinize class and power in the United States. All eight panels were on display for the duration of the exhibition’s run.

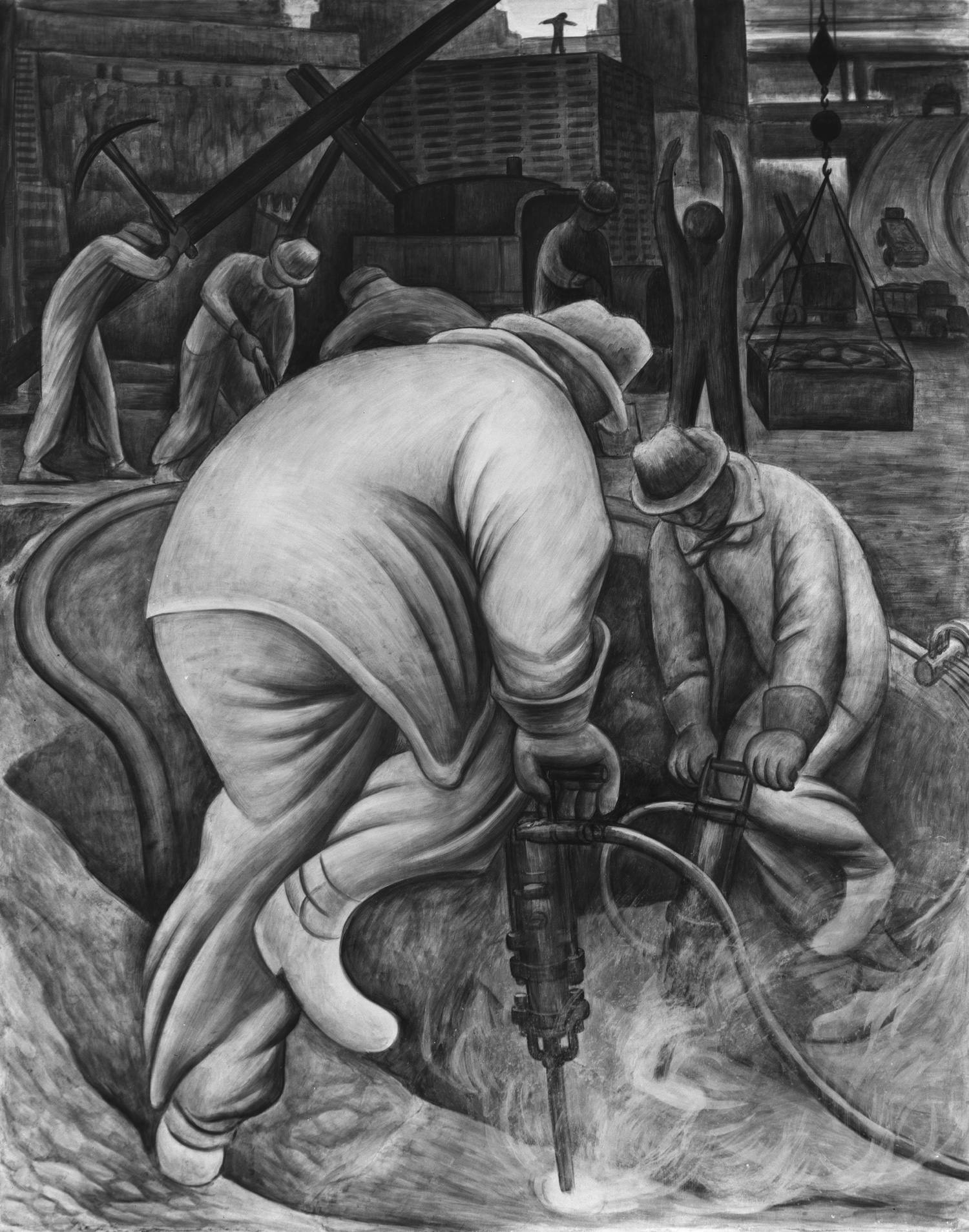

The five murals from the 1931 retrospective that were on view in Diego Rivera: Murals for The Museum of Modern Art are Agrarian Leader Zapata (1931), Indian Warrior (1931), The Uprising (1931), Frozen Assets (1931–32), and Electric Power (1931–32). Two of the three remaining murals—Liberation of the Peon (1931) and Pneumatic Drilling (1931–32)— were represented in the exhibition through full-scale working drawings.

The exhibition also featured archival materials, including designs and photographs drawn from MoMA’s archives, related to the commission and production of the works.

THE PORTABLE MURALS

The portable mural Agrarian Leader Zapata depicts Emiliano Zapata, a champion of agrarian reform and a key protagonist in the Mexican Revolution, leading a band of peasant rebels armed with provisional weapons, including farming tools. With the bridle of a white horse in his hand, Zapata stands triumphantly beside the dead body of a hacienda owner. Though Zapata was often vilified in contemporary press as a treacherous bandit, Rivera immortalized him as a hero and glorified the victory of the Revolution in an image of violent but just vengeance. In addition to Agrarian Leader Zapata, a large-scale cartoon study of the work along with an X-ray of the mural are on view. The latter reveals the internal skeleton of one of Rivera’s portable murals for the first time.

Of all the panels Rivera made for MoMA, Indian Warrior reaches back farthest into Mexican history, to the Spanish Conquest of the early 16th century. An Aztec warrior wearing a jaguar costume stabs an armored conquistador in the throat with a stone knife. The details of Aztec culture in the image reflect Rivera’s extensive study of pre-Columbian art, of which he was an avid collector. Simultaneously, the work demonstrates the artist’s intimate knowledge of European artistic tradition—the conquistador’s sharply foreshortened body and carefully modeled armor recall works by Renaissance masters, which Rivera studied firsthand on an extended trip to Italy in 1920.

In The Uprising, a woman in modern dress with a baby at her hip and a man dressed like an urban worker fend off an attack by a uniformed soldier. Behind them, a riotous crowd clashes with more soldiers, who force demonstrators to the ground. In the early 1930s, an era of widespread labor unrest, images of the violent repression of strikes would have resonated with both U.S. and Latin American audiences. The red banners and clenched fist that rise above the crowd offered internationally comprehensible signs of workers’ resistance.

Situated below a view of New York City’s jagged skyline, a steel-and-cement power plant interior dominates Electric Power. While there were no major hydroelectric plants in sight of the city when Rivera made the work, the technology was a major topic in the United States; the Federal Power Act was revised in 1930, and construction began on the Hoover Dam in 1931. Rivera peeled back his plant’s facade to bring the workers—deep in the inner workings of its machinery—into the space of the viewer, exposing the human labor that powers the modern city.

In Frozen Assets, the most ambitious and controversial of Rivera’s New York–themed panels, the artist coupled his appreciation for the city’s distinctive vertical architecture with a critique of its economic inequities. The panel’s upper portion features a dramatic sequence of recognizable skyscrapers, most of which had been completed within a few years of Rivera’s arrival in the city. In front of them are cranes and the steel frames of buildings in progress—emblems of New York’s construction boom. In the middle section, a steel-and-glass shed serves as a shelter for rows of sleeping men, evoking the dispossessed labor that made such growth possible. Below, a bank’s waiting room accommodates a guard, a clerk, and a trio of figures eager to inspect their mounting assets in the vault beyond. Rivera’s jarring vision of the city struck a chord in 1932, at the nadir of the Great Depression.

Large-scale cartoon drawings for two of the murals not in the exhibition were also on view. In the drawing for Liberation of the Peon, Rivera developed a harrowing narrative of corporal punishment. It features a laborer, beaten and left to die, cut down from a post by sympathetic revolutionary soldiers, who tend to his broken body.

In the drawing for Pneumatic Drilling, two figures use a pneumatic drill and jackhammer to bore into Manhattan’s granite foundation. Rivera later identified this scene as depicting preparations for the construction of Rockefeller Center, at the time the largest building project ever funded wholly by private capital. Because the surface of a fresco panel dries quickly, Rivera used full-scale cartoons like these to develop his compositions before applying pigment to the wet plaster. He would then transfer them to or replicate them on the mural’s surface.

ADDITIONAL WORKS

Additional works related to the 1931 commission were also on view, including The Rivals (1931), a large-scale painting that depicts a fiesta in Tehuantepec, an area in the south of Mexico that Rivera first visited in 1922. Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, one of the founders of MoMA and an important collector of Rivera’s work, commissioned this canvas as part of a significant purchase of paintings and sketches that helped defray the cost of the artist’s trip to New York for his exhibition at MoMA.

Also on view was Market Scene, which depicts an Indian woman and child offering a tribute of fruit and fish to a Spanish conqueror. This work, from 1930, was Rivera’s first attempt to create a portable mural. His experimentation may have been prompted by his upcoming retrospective at MoMA, which was then in the early planning stages. The artist’s innovative response—a freestanding fresco panel—allowed for both exhibition and sale of his mural work.

While Rivera was in New York in 1931, he began discussions for a commission at Rockefeller Center. Materials related to the commission were on view, including preparatory drawings for the Rockefeller mural, Man at the Crossroads, and photographs of the mural in progress, among other materials. Rivera began work on the mural in March 1933, but by mid-May he had been discharged from the project and his fresco covered with a tarp, concealed until it was chipped from the wall the following year. The most frequently cited reason for the sudden dismissal of the artist is Rivera’s inclusion of a portrait of Vladimir Lenin—a detail that provoked inflammatory headlines. Rivera’s patrons requested that the remove the offending image, but he refused.

PUBLICATION:

The vividly illustrated publication Diego Rivera: Murals for The Museum of Modern Art presents all eight frescoes produced by Rivera for the 1931 exhibition in rich detail. An essay by curator Leah Dickerman discusses the history and context of Rivera’s fresco works; his political engagements in Mexico, the United States, and the Soviet Union; and his complex interactions with patrons. Anna Indych-López, a specialist in Mexican modernism, offers in-depth analysis of each of the eight fresco panels. Conservators Anny Aviram and Cynthia Albertson examine Rivera’s working process, materials, and technical innovations. Also included is a selected chronology of the artist’s life and work, focusing on the events that led to his New York show. Together these elements provide a compelling perspective on the intersection of art making and radical politics in the 1930s. 148 pages, 129 illustrations.

More Images:

Sugar Cane