Venues

New York State Museum, Albany May 21 - July 11, 1999

Asheville Art Museum Asheville, NC through Oct. 31 1999

Orange County Museum of Art, Newport Beach CA through January 23, 2000

Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, November 9, 2000 - January 14, 2001

The dramatic loneliness of an Edward Hopper cityscape and the frantic pace of a John Sloan street corner were among the realistic images displayed as part of In the City: Urban Views 1900-1940 Masterpieces from the Whitney Museum of Art.

The turbulence of World War I and the Great Depression fueled American artists as they depicted city life in the first 40 years of this century.

Many of the works in the latest exhibition of the series featured the Ashcan School led by Robert Henri. As their figurehead, Henri, encouraged these artists - including Sloan, Everett Shinn and George Luks - to paint urban life as they saw it and to break with the sentimental idealism of academic art.

These artists were the first in this country to draw their inspiration from modern city life in all its manifestations, not only the fashionable but the seamy side as well. Many got their start as newspaper artists, who would make hurried sketches on deadline to accompany a story in the next day's paper. They would be dispatched to a fire or riot scene, where they would take notes -- mentally and on paper -- hurry back to the newsroom and complete an illustration.

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney built her collection by supporting these artists who responded to and recorded urban life. In 1914 she established the Whitney Studio, her first art gallery that soon became an important gathering place for artists. Hopper, Reginald Marsh and Sloan had their first solo exhibitions there. In 1931, Mrs. Whitney opened the Whitney Museum of American Art to exhibit work by living artists. Her founding collection of 700 works served as the focus of the Whitney Museum in the 1930s and 1940s.

From a review of the Asheville show: (images, links added)

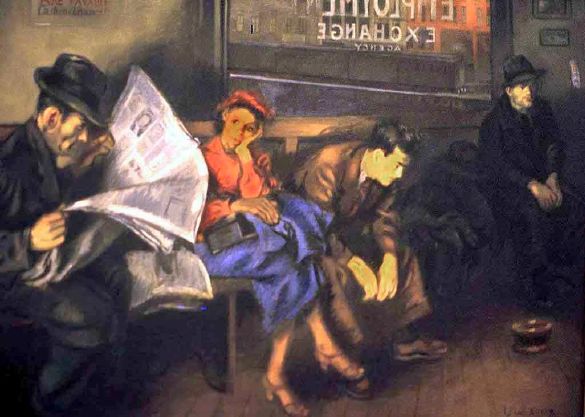

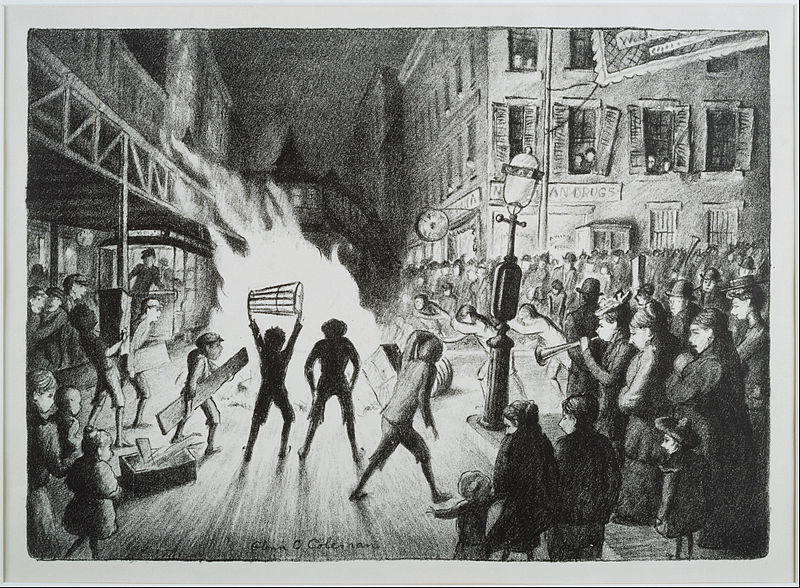

The third room displays grim, Depression-era scenes of unemployment lines and political unrest -- most strikingly,

Isaac Soyer's "Employment Agency,"

and

Glenn Coleman's "Election Night Bonfire."

The fourth gallery looks ahead to a world more familiar to us in subsequent decades, charting both the city's changing physical environment and the move away from what had been, up till then, mostly realist art.

Louis Guglielmi's stark, surrealist-inspired "Terror in Brooklyn"

and the bold graphics and stylized figures of

Jacob Lawrence's "Tombstones"

herald fundamental aesthetic change.

At the same time, the exhibit traces the metamorphosis of several individual artists' styles, particularly Edward Hopper: Six very different Hopper works are featured, including

"Soir Bleu" (1914),

a startling depiction -- influenced by the time Hopper spent in France -- of a group of Parisians drinking at an outdoor cafe. There's a vaguely sinister feel to the piece, reinforced by the solemn clown smoking a cigarette near the composition's center. The work's flatness, both in style and tone, creates a kind of "dead" sensation that belies its brilliant blue background. One of Hopper's favorite pieces, "Soir Bleu" was soundly trounced by critics at its first New York showing in 1915; he never exhibited it again before donating it to the Whitney.

That same flatness also looks ahead to Hopper's more famous later work -- such as the haunted landscape of

"Apartment Houses, Harlem River" (1930),

a vaguely eerie study, done in muted blues, greens and grays, of a row of almost identical apartment buildings along the river. The muted lights that appear in a few windows are the only evidence of human life....

Everett Shinn's "Under the Elevated" (believed to be circa 1912)

is a prime example of the Ashcan School approach to art. The work depicts a gloomy winter street scene: Dark, run-down shops (like the Smoke & Chew) and flophouses (Rover's Hotel) provide a backdrop for a dark mass of almost faceless people, painted mostly in shades of black, huddled in one corner. Muted street lamps provide the only light, and the cold is almost palpable.

John Sloan's "Sixth Avenue Elevated at Third Street" (1928)

presents a vastly different picture, in keeping with the spirit of the time. Instead of darkness, we're met with the blazing lights of the el at the top of the canvas. Below, brightly lit shops replace the gloomy buildings of "Under the Elevated," and the raucous Jazz Age sensibility is captured in groups of flappers and elegantly dressed men and women cavorting on the street.

Reginald Marsh's "Why Not Use the 'L'" (1930)

captures the miserable tone of life after the stock-market crash of 1929, but with wry humor and irony. Beneath a sign advertising the joys of riding the "open-air elevated" sit three figures -- dead-tired, numb and desperate -- clearly not enjoying the ride. A newspaper casually tossed on the floor screams the headline, "Does the sex urge explain Judge Crater's strange disappearance?"

And Francis Criss' "Sixth Avenue El" (1937)

also anticipates the move toward abstraction. Here, both the el and the city beneath it dissolve in a geometric hodgepodge of flat shapes, marked by deeply textured paint in plain primary and secondary colors..

{Editor: see more outstanding El images here}

Mabel Dwight's "Aquarium" and

"The Clinch, Movie Theatre" (both 1928)

depict leisure pursuits available to the masses.

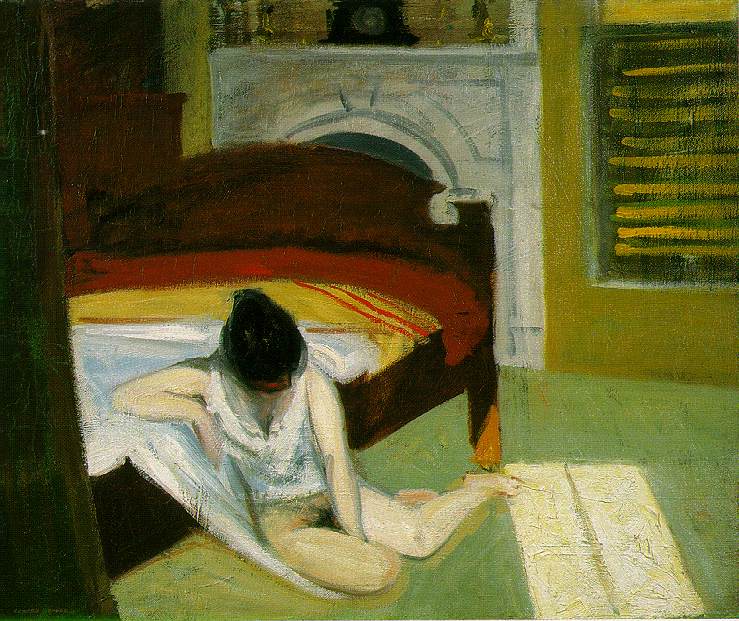

Quiet studies of women in repose, such as

Thomas Dewing's formal, portrait-like "Lady in a Green Dress" and

Edward Hopper's "Summer Interior"

-- a beautiful work done in acid greens and rusts, featuring a partially nude woman lounging on the floor of her simple but comfortably appointed room -- capture the sedentary pastimes of the upper classes...

Reginald Marsh.. gives us

"Ten Cents a Dance" (1933) and

"Minsky's Chorus" (1935).

"Ten Cents" is a voluptuous group portrait: Women dressed in form-fitting, jewel-toned dresses stare with fixed smirks at an invisible audience; a whiff of something sexual permeates the piece...

"Minsky's Chorus" is a lush, sensual, slightly sullied study of burlesque dancers. A gaggle of scantily clad women fill a stage -- their seductive gyrations almost tangible. The scene is awash in slightly faded golds, punctuated by the bright-red garters and feather headpieces of the dancers. Two leering men lounge in one corner, while musicians in the pit fill the foreground.

Excellent article on the exhibition

More images from the exhibition:

Maurice Prendergast, Central Park, 1901,1901, watercolor on paper, 15 1/16 x 22 1/8 inches, Collection of Whitney Museum;

Robert Henri, Blackwell's Island, East River, 1900, oil on canvas, 20 x 24 inches, Collection of Whitney Museum;

William Glackens,Parade, Washington Square, 1912, oil on canvas, 26 31 inches, Collection

of Whitney Museum

John Sloan, Backyards, Greenwich Village, 1914, oil on canvas, 26 x 32 inches, Collection of Whitney Museum

Everett Shinn, Girl Dancing, 1905, watercolor and conte crayon on cardboard, 5 3/4 x 7 13/16 inches, Collection of Whitney Museum

Abraham Walkowitz, Cityscape, c. 1915, oil on canvas, 25 x 18 inches, Collection of Whitney Museum

Stuart Davis, The Back Room, oil on canvas, 30 1/4 x 37 1/2 inches, Collection of Whitney Museum

Guy Pene Du Bois, Café Monnot, c. 1928-29, oil on canvas, 22 x 18 1/2 inches, Collection of Whitney Museum

Raphael Soyer, Office Girls, 1936, oil on canvas, 26 x 24 inches, Collection of Whitney Museum

Philip Evergood, Through the Mill, 1940, oil on canvas, 36 x 52 inches, Collection of Whitney Museum