The Smithsonian American Art Museum organized the nationally traveling exhibition “Modern Masters from the Smithsonian American Art Museum.”

Venues

Patricia and Philip Frost Art Museum; Florida International University, Miami.

November 29, 2008- March 1, 2009

Westmoreland Museum of American Art, Greensburg, Pennsylvania.

June 14-September 6, 2009

Dayton Art Institute, Dayton, Ohio.

October 10-January 2, 2010

Telfair Museum of Art, Savannah, Georgia.

November 13- February 5, 2011

Cheekwood Botanical Garden and Museum of Art, Nashville, Tennessee.

March 19 -June 19, 2011

Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

October 7- January 1, 2012

The exhibition featured 43 key paintings and sculptures by 31 of the most celebrated artists who came to maturity in the 1950s. “Modern Masters” examines the complex and varied nature of American abstract art in the mid-20th century through three broadly conceived themes that span two decades of creative genius—“Significant Gestures,” “Optics and Order” and “New Images of Man.”

“The exhibition introduces the richness and complexity of American art in the years following World War II. We are thrilled that the deep holdings of the Smithsonian American Art Museum allow us to share important works by leading abstract painters and sculptors with audiences throughout the country.” said Virginia Mecklenburg, senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum who organized the exhibition.

The decades following World War II were stimulating times for American art. While some vanguard artists began to paint or sculpt in the 1930s as beneficiaries of WPA-era government support, other immigrant artists fled to the United States as Nazi power grew in Germany. A few artists were highly educated; others left school at an early age to pursue their art. Working in New York, California, the South and abroad, these artists blended knowledge gleaned from the old masters and modernists Picasso and Matisse with philosophy and ancient mythology to create abstract compositions that addressed current social concerns and personal history. Some mixed hardware-store paint with expensive artist colors and bits of paper torn from magazines, linking their work with contemporary life.

Aided in their efforts by a group of young dealers, prominent critics and influential editors, abstract artists gained credibility. Abstraction was no longer dismissed as irrelevant or incomprehensible, but instead became a widely discussed national style. Weekly magazines such as Life, Time and Newsweek brought images of contemporary abstraction to households throughout the country while New York museums toured exhibitions to the capitals of Europe. Galleries discovered new markets in the country’s growing middle-class, and newspapers celebrated American culture as an equal partner with technology in catapulting the United States to preeminence on the world stage.

By the late 1950s, Sam Francis, Philip Guston, Hans Hofmann, Franz Kline and other painters and sculptors who embraced abstraction early in the decade enjoyed success, celebrity and international acclaim.

“Significant Gestures” explores the autographic mark, executed in sweeping strokes of brilliant color that became the expressive vehicle for Francis, Hofmann and Kline as well as Michael Goldberg and Joan Mitchell. These artists and others, affected by World War II, became known as abstract expressionists. For each artist, the natural world, recent discoveries in physics and the built environment provided motifs for powerful canvases of color and light.

“Optics and Order” examines the artists who investigated ideas such as the exploration of mathematical proportion and carefully balanced color. This section, which highlights Josef Albers, also features Ad Reinhardt, who developed visual vocabularies that used rectilinear shapes to meld intellectual idea with emotional content, and artworks by like-minded artists Ilya Bolotowsky, Louise Nevelson and Esteban Vicente. A sculpture by Anne Truitt, whose majestic columns transform childhood memories of Maryland’s Eastern Shore into totemic structures, is included in this section as well.

“New Images of Man” includes works by Romare Bearden, Jim Dine, David Driskell, Grace Hartigan, Nathan Oliveira, Larry Rivers and several others, each of whom searched their surroundings and personal lives for vignettes emblematic of larger, universal concerns. Issues such as tragedy, interpersonal communication and racial relations guided the creation of these artists’ pieces.

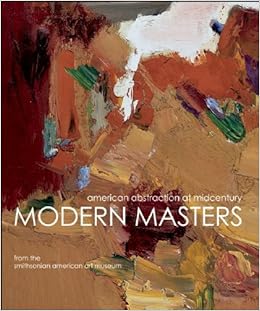

Catalogue

Modern Masters: American Abstraction at Midcentury, the fully illustrated catalog copublished by the Smithsonian American Art Museum and D Giles Limited (London), is written by Mecklenburg with contributions by Tiffany Farrell. The book features an essay and biographical information on the 31 artists whose work is included in the exhibition.

From a review: (images added)

At Dayton Art Institute, I gladly reacquainted myself with Reinhardt’s austere, sublime black squares touched slightly by blue or plum in

“Abstract Painting No. 4” (1961)

and wanted to say, “It’s been too long” to Gottlieb’s magisterial

“Three Discs” (1960)....

New to me was the earliest work in the show, Reinhardt’s bright and jazzy — who knew? —

untitled, high-colored abstraction of 1940.

It came into the collection after I was back in Ohio, as did Hans Hofmann’s “Fermented Soil” (1965),

Hans Hofmann; Fermented Soil, 1965; Oil on canvas, 48 x 60 inches; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of S.C. Johnson and Son, Inc.

perhaps my favorite piece in the exhibition, with its rough surface, strong color and complicated interactions.

The exhibition is helpfully organized into three sections. “Significant Gestures” includes that master of the gesture, Kline, and others. “Optics and Order” highlights several artists, including Albers, all of whom endlessly explore the effect of colors on each other. A late-ish (1978) contribution to this field by Ilya Bolotowsky,

“Tondo Variation in Red,”

looks fresh as if made yesterday, although the same artist’s “Architectural Variations” (1949) seems oddly dated.

Cincinnati’s Jim Dine turns up in the final section, “New Images of Man,” which recognizes that figural art never really went away.

Dine’s “The Valiant Red Car”

is close to billboard size and rewards attention.

Nearby is one of my surprises of the show,

Nathan Oliveira’s “Nineteen Twenty-Nine” (1961),

an arresting portrait of his mother perfectly hung, almost by itself, with perfect lighting to bring out the textured surface.

Images from the Exhibition

Franz Kline, Untitled, 1961, acrylic, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase from the Vincent Melzac Collection through the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquisition Program

Hartigan Modern Cycle 1980