|

|

|

Date : April 12 - June 15, 2014

Venue : Gallery N1

Hosted by: National Museum of China

Réunion des musées nationaux - Grand Palais

This

exhibition gives Chinese viewers the chance to discover masterpieces

that are symbolic of the museums they belong to. Each painting

represents an important era or artistic movement in France. The

paintings tell many stories: the stories they depict, but also stories

about the artists and what they wished to express. Although each

painting is presented independently, the group forms a history of French

art, from the Renaissance to after World War Two.

Francois

Ⅰ and Louis ⅩⅣ were both patrons of the arts who helped establish

French art collections. The portraits of these kings highlight the

State’s role in protecting and promoting artists.

Pablo

Picasso and Fernand Léger were both members of France’s pioneering 20th

century avant-garde scene. The two painters, who were both part of the

Cubist movement, show the different forms taken by modern art.

Despite

their differences, these artists--Clouet, Rigaud, Picasso and Léger--

all painted pictures of people, producing images that appealed to

viewers’ emotions. Whether they lived in a monarchy or a republic, they

used portraits to explore different ways of portraying the world and

reflections of reality.

Regardless

of the era or artistic movement, there are clear parallels between

artists such as La Tour and Soulages, or Fragonard and Renoir. Some

painters focused on light and dark, and others on love, seduction,

relationships between men and women--and were passionate about using

colour. These timeless themes linking classical and modern art tell the

story of an extremely rich heritage.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jean Clouet

Portrait de François I er, roi de France

Paris, musée du Louvre

From

the 15th century onwards, the art of portrait painting spread

throughout the Western world. In Europe, monarchs used portraits to

influence how they were seen in life and after death. This portrait of

François I by Jean Clouet is one example.

In this painting, the

artist underlines the French king’s power by emphasizing his broad

shoulders, sword, Grand Master pendant of the Order of Saint Michael and

gold-embroidered clothing. François I is wearing a beret, but the crown

is also visible behind him.

François I was a major patron of

artists and the arts. He was fascinated by new ideas emerging in Italy

as part of the Renaissance movement. He invited many Italian artists to

France to work for him, including the painter Leonardo da Vinci. His

castle at Fontainebleau became a centre for artistic creation renowned

throughout Europe.

|

|

George de La Tour

Saint Joseph charpentier

Paris, musée du Louvre

Georges de la Tour is a talented painter of night scenes. In his paintings, the only sources of light are candles or firelight.

This

painting is of a carpenter working at night to the light of a candle

held by his son. The carpenter is Joseph, Jesus’ adoptive father in the

Christian religion. The child’s face is unnaturally bright, to reflect

his holiness. However, his dirty fingers and fingernails remind the

viewer that he is real.

The looks exchanged by the old man and

the child are central to the painting. Joseph’s tender gaze shows his

love for the boy. He is perhaps frowning because he is worried about his

son’s future. The wooden beam on which he is working is a reminder of

the cross on which Jesus died.

Although the painting has a

religious theme, the childhood scene appeals to universal emotions. The

subject matter and characters affect all viewers. Georges de la Tour has

produced a simple image that conveys the holiness in everyday life, an

approach encouraged by the Catholic Church.

|

|

Jean Honoré Fragonard

Le Verrou

Paris, musée du Louvre

Early

in his career, Fragonard painted serious works inspired by ancient

history. However, he later chose to focus on less serious subjects, such

as love and sensuality.

This painting is about forbidden passion

between a man and a woman. Its composition is remarkable: an invisible

diagonal line runs from the apple to the bolt. The apple symbolises sin

in the Western world, and the bolt reflects the idea that there is no

turning back. The painting seems to capture the moment when time

stops—the point of no return.

The scene was possibly inspired by

18th century libertine novels, which were condemned by the Church.

However, the painting was presented with another of Fragonard’s works

that had a religious theme, The Adoration of the Shepherds. This

second painting shows shepherds adoring the baby Jesus. Seen together,

the works present two different forms of love: the love that brings us

closer to God and the love between men and women.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hyacinthe Rigaud

Portrait en pied de Louis XIV, âgé de 63 ans, en grand costume royal

Versailles, châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon

Louis

XIV changed the course of Western history. During his reign

(1643-1715), Versailles became the capital of France, and his castle

became an artistic centre renowned throughout the rest of Europe.

When

he was 63, Louis XIV decided to send a portrait of himself to his

grandson Philip V, King of Spain. He asked Hyacinthe Rigaud to complete

this painting. Extremely satisfied with the result, he then asked Rigaud

to paint a second copy for his own castle. In the end, both paintings

stayed at Versailles. It is the second painting that is displayed here.

In

this painting, Louis XIV appears with several symbols of power,

including the throne, the sceptre and the crown. His blue robes are

embroidered with the fleur-de-lis, the emblem of the French royal

family. These robes were worn during coronation, a religious ceremony

giving the king royal power. The composition of the painting became a

reference for official portraits in later years.

Hyacinthe Rigaud

became famous after painting this portrait. He had a real talent for

capturing the personality of his models, as well as the dignity of their

rank. He completed many portraits for members of the European nobility.

|

|

|

│MUSÉE D’ORSAY│

|

|

photography by Chen Lusheng More>>

The

Musée d’Orsay opened to the public on 9 December 1986. It is home to

many different forms of artistic creation produced in the Western world

from 1848 to 1914.

The museum has an unusual history. It is

located in central Paris, in the former Gare d’Orsay train station on

the banks of the Seine River opposite the Tuileries gardens. This train

station was built for the Universal Exhibition in 1900. In 1978, the

building was listed as a protected historical monument. The Musée

d’Orsay public institution was created to manage the museum project.

Since

2010, the Musée d’Orsay public institution has also run the Musée de

l’Orangerie, where Claude Monet’s famous Water Lilies are exhibited.

The

Musée d’Orsay has extensive collections in several fields: painting,

sculpture, decorative arts, architecture and photography. With

masterpieces by artists such as Renoir, Courbet, Cézanne, Monet, Rodin

and Van Gogh, it is an internationally renowned institution.

|

|

Auguste Renoir Le Bal du Moulin de la Galette Paris, musée d’Orsay

At

the end of the 19th century, Paris underwent major transformations,

like the rest of French society. To improve traffic, new roads were

built. Shops, cabarets and cafés became new meeting places, as seen in

many paintings.

During this period, several painters decided to

move to Montmartre, an area located on a hill to the north of Paris.

With its narrow streets and old houses, Montmartre had a village-like

atmosphere. Auguste Renoir was one of the first painters to set up here.

He discovered a population of workers and city dwellers who were

determined to enjoy themselves.

Artists, workers, friends and

passers-by met at guinguettes, open-air dance halls like the Moulin de

la Galette in this painting. This scene is typical of the atmosphere at

the time. The freshness and beauty of the dancers inspired Renoir, who

took pleasure in painting the era’s joie de vivre.

|

|

Auguste Renoir

La Balançoire

Paris, musée d’Orsay

Auguste

Renoir, Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro were all founding members of

Impressionism, an artistic movement that emerged in France in the second

half of the 19th century. The Impressionists’paintings were often

completed outdoors and featured bright colours. Although critics

attacked these works, they went on to gain recognition around the world.

Classical

painters liked to present major historical, mythological or religious

themes. The Impressionists chose to paint the world as they saw it,

often focusing on landscapes.

In this painting, Renoir captures a

particular time of day, when sunlight filters through the trees. The

shadows are blue and the sunlight is pink —the artist chooses colours

based on his impressions of the moment. Similarly, the young woman’s

white dress is actually many different colours of paint that are applied

quickly to the canvas. This style is typical of the Impressionist

movement.

|

|

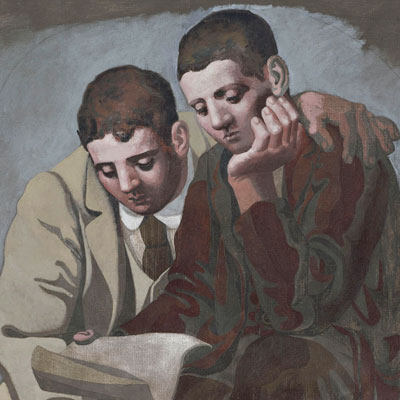

Pablo Picasso

La Lecture de la lettre

Paris, musée Picasso

Pablo

Picasso was remarkable because he changed painting styles regularly

over the course of his life. It is difficult to believe that the same

artist painted Reading the Letter and The Matador.

As a pioneer

of the Cubist movement, Picasso used simple geometric forms to show the

world from different angles. However, after World War One, he returned

to a more classical way of portraying people, as in this painting.

Two

men are sitting side by side on a stone. They occupy all of the canvas.

Their suits contrast with their natural surroundings. The men are

friends —one has his arm around the other’s shoulders and they are

sitting close to each other. The letter and the book suggest writing and

literature.

Many consider this painting is of Pablo Picasso and

French author Guillaume Apollinaire. The two men met in Paris in 1904

and became great friends. This artwork, completed in 1921, is thought to

be Picasso’s tribute to his friend, who died in 1918.

|

Fernand Léger

Composition aux trois figures

Paris, Centre Pompidou, musée national d’Art moderne / Centre de création industrielle

Early

in his career, Fernand Léger focused more on geometrical shapes,

mechanisms and everyday objects than on people. Composition with Three

Figures, which was painted in 1932, was the beginning of a new era for

him.

From the 1930s onwards, Léger wanted to attract a wider

audience. To do so, he chose to work on larger canvases, focused on

figures, and used more realistic shapes. However, he did not paint these

figures to tell stories. Instead, he assembled the different shapes to

create a visual poem.

Léger’s work explores contrasts. This

painting is all about opposition: between animate and inanimate objects,

the colour yellow and the figures in black and white, and the volume of

the shapes and the one-dimensional background.

When Léger

painted Composition with Three Figures, he made no secret of his

personal and political views. He considered humanity, education and

living conditions were extremely important subjects. In 1936, the French

government bought Composition with Three Figures to recognise the

artist and his commitments. After World War Two, Léger officially joined

the French Communist Party.

|

|

Pierre Soulages

Peinture, 195 × 130 cm, 10 août 1956

Paris, Centre Pompidou, musée national d’Art moderne / Centre de création industrielle

The

French painter Pierre Soulages was born in 1919 and became a key figure

in abstract art. His work explores the colour black. His paintings do

not express messages but, at first glance, seem to be simple

associations of shapes and colours. Each of his paintings is an

invitation to take part in a unique experience.

He gives viewers

the freedom to interpret his paintings in their own way, in line with

their own culture, history, perceptions and feelings.

“The painting is not a sign, it is a thing. Through it, the senses come to be made, and unmade.”

PIERRE SOULAGES, Le prétendu métier perdu (the supposedly lost profession), 1981

|

|

|

|