26 January to 17 May 2020

Edward Hopper (1882–1967) is widely acknowledged as one of the most

significant artists of the 20th century. In Europe, he is known mainly

for his oil paintings of urban life scenes dating from the 1920s

to 1960s, some of which have become highly popular images. Less

attention has so far been paid to his landscapes. Surprisingly, no

exhibition to date has dealt comprehensively with Hopper’s approach

to American landscape. From 26 January to 17 May 2020, the Fondation Beyeler

in Basel is presenting an extensive exhibition of iconic landscape

paintings in oil as well as a selection of watercolors and drawings.

This will also be the first time Hopper’s works are shown in an

exhibition in German-speaking Switzerland.

Hopper was born in Nyack, New York. After training as an illustrator, he studied painting at the New York School of Art until 1906. Next to German, French and Russian literature, the young artist found key reference points in painters such as Diego Velázquez, Francisco de Goya, Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet. Although Hopper long worked mainly as an illustrator, his fame rests primarily on his oil paintings, which attest to his deep interest in color and his virtuosity in representing light and shadow. Moreover, on the basis of his observations Hopper was able to establish a personal aesthetics that has influenced not

only painting but also popular culture, photography and film.

Hopper was born in Nyack, New York. After training as an illustrator, he studied painting at the New York School of Art until 1906. Next to German, French and Russian literature, the young artist found key reference points in painters such as Diego Velázquez, Francisco de Goya, Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet. Although Hopper long worked mainly as an illustrator, his fame rests primarily on his oil paintings, which attest to his deep interest in color and his virtuosity in representing light and shadow. Moreover, on the basis of his observations Hopper was able to establish a personal aesthetics that has influenced not

only painting but also popular culture, photography and film.

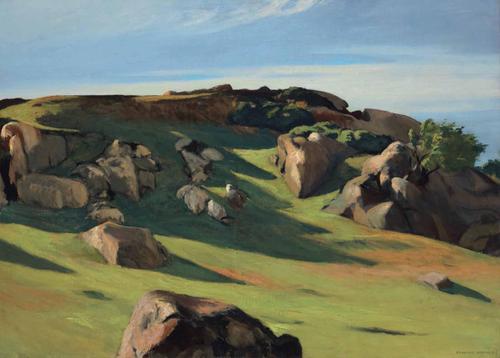

The idea for this exhibition arose when Cape Ann Granite,

a landscape painted by Edward Hopper in 1928, joined the collection of

the Fondation Beyeler as a permanent loan [it sold at Christie's in

2018]. For several decades, the work belonged to the celebrated

Rockefeller collection, and it dates from a time in which Hopper

received growing attention from critics, curators and the public. In

1929, he was thus invited to take part in the Museum of Modern Art’s

second exhibition, Paintings by Nineteen Living Americans.

In the art-historical tradition, “landscape” signifies an image of

nature as opposed to ever-changing actual “nature”, which as such cannot

be fixed as an image. Landscape painting always shows the impact of

man on nature and Hopper’s paintings reflect this in a subtle and

multifaceted way. He thus established a distinctly modern approach to a

time-honored genre of art history. Unlike academic tradition,

Hopper’s landscapes seem unbounded; in one’s mind, they are infinite and

always appear to be showing only a small part of an immense whole.

Hopper’s American landscapes are geometrically clear compositions. Their main elements are houses, symbolizing human settlement. Railroad tracks structure the images horizontally and stand for man’s endeavor to conquer wide expanses of space. A vast sky as well as specific lighting moods − bright midday sunlight and the glimmer of dusk − illustrate the immensity and constant transformation of nature even in an actually static landscape painting. A lighthouse can thus become a point of reference in the vastness of the sea and the coastline.

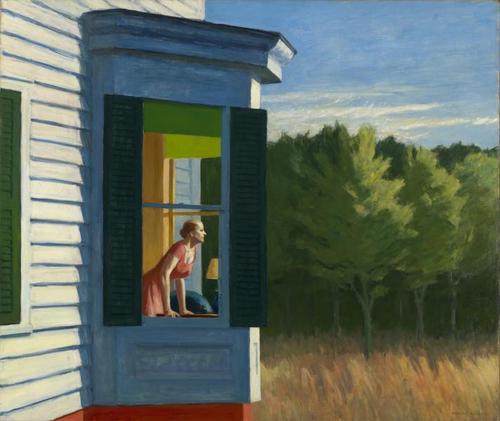

Hopper’s landscape paintings seem to deal with something invisible, occurring outside the image, as illustrated for example by Cape Cod Morning (1950): a woman is looking out from a bay window, her face bathed in sunlight, staring at something the viewer cannot see because it is located beyond the pictorial space. Hopper’s visible landscapes always have an invisible, subjective counterpart that appears inside the viewer. As is the case with all his paintings, Hopper’s landscapes are defined by melancholy and loneliness. They often convey a sense of eeriness and apprehension. Hopper also shows the sometimes brutal intrusion of man into nature by confronting natural and urban landscapes. Hopper played a major role in establishing the notion of a melancholy America, defined also by the dark sides of progress – a vast, unlimited space, which became immensely popular especially through its development in films such as Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1959), Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas (1984) or Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves (1990).

Hopper’s American landscapes are geometrically clear compositions. Their main elements are houses, symbolizing human settlement. Railroad tracks structure the images horizontally and stand for man’s endeavor to conquer wide expanses of space. A vast sky as well as specific lighting moods − bright midday sunlight and the glimmer of dusk − illustrate the immensity and constant transformation of nature even in an actually static landscape painting. A lighthouse can thus become a point of reference in the vastness of the sea and the coastline.

Hopper’s landscape paintings seem to deal with something invisible, occurring outside the image, as illustrated for example by Cape Cod Morning (1950): a woman is looking out from a bay window, her face bathed in sunlight, staring at something the viewer cannot see because it is located beyond the pictorial space. Hopper’s visible landscapes always have an invisible, subjective counterpart that appears inside the viewer. As is the case with all his paintings, Hopper’s landscapes are defined by melancholy and loneliness. They often convey a sense of eeriness and apprehension. Hopper also shows the sometimes brutal intrusion of man into nature by confronting natural and urban landscapes. Hopper played a major role in establishing the notion of a melancholy America, defined also by the dark sides of progress – a vast, unlimited space, which became immensely popular especially through its development in films such as Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (1959), Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas (1984) or Kevin Costner’s Dances with Wolves (1990).

As

a special highlight, filmmaker Wim Wenders has produced a 3D short film

entitled Two or Three Things I Know about Hopper, screened in a

dedicated room. The film is Wenders’ personal tribute to Edward Hopper,

who made a lasting impression on him and influenced his cinematic work.

He travelled across the USA on a quest for “Hopper’s spirit”, condensing

the resulting footage into a film that will premiere at

the exhibition’s opening. In a poetic and moving way, the film shows

just how indebted cinema is to Edward Hopper as well as the extent to

which Hopper was in turn influenced by movies.

The exhibition Edward Hopper

comprises 65 works dating from 1909 to 1965. It is organized by the

Fondation Beyeler in cooperation with the Whitney Museum of American

Art, New York, the worldwide major repository of Hopper’s work.