Rogier van der Weyden (ca. 1400–1464). The Virgin and Child, ca. 1460, oil on panel transferred to canvas transferred to masonite, 19 1/2 × 12 1/2 in. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

Rogier van der Weyden (ca. 1400–1464) Portrait of Philippe de Croÿ, ca. 1460, oil on panel, 20 × 12 1/2 in. The Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp. Photo © Lukas Art/Koninkijk Musuem voor Schone Kunsten.

An exhibition of 29 paintings by Renaissance luminaries such as Domenico Ghirlandaio, Hans Memling, Pietro Perugino, and Rogier van der Weyden, complemented by six rarely exhibited illuminated manuscripts, has been organized by The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens and is on view in the MaryLou and George Boone Gallery from Sept. 28, 2013, through Jan. 13, 2014. Accompanied by a book of the same title, “Face to Face: Flanders, Florence, and Renaissance Painting” explores the relatively little-known fact that Flemish painting helped make possible the innovative, sophisticated, and beautiful works of the Italian Renaissance.

While many exhibitions have shed light on the beauty of 15th-century Flemish painting, and even more have celebrated the glory of Italian Renaissance painting, “Face to Face” (inspired by the 2008 exhibition “Firenze e gli Antichi Paesi Bassi 1430–1530,” presented at the Palazzo Pitti in Florence) is the first in the United States to examine the theme, showing the results of artistic contact between the creative centers in Flanders (specifically those located in present-day Belgium) and Florence.

“Face to Face” marks the first time viewers in the Los Angeles area will be able to see The Huntington’s acclaimed Virgin and Child (ca. 1460) by Flemish painter Rogier van der Weyden (ca. 1400–1464) displayed alongside its companion diptych panel. Portrait of Philippe de Croÿ, on loan from the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp, was originally the right half of the two-panel painting hinged to open and close like a book—a common format at the time that enabled the works to stand open on a table or altar.

With paintings from the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence, the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., among others, the exhibition juxtaposes Flemish and Italian works in thematic groupings, addressing the form of the diptych, the depiction of the face of Christ, the evolution of portraiture, the elements of landscape painting, and the virtuosic rendering of materials and objects.

“Face to Face” is co-curated by Catherine Hess, chief curator of European art at The Huntington, and Paula Nuttall, author of From Flanders to Florence: The Impact of Netherlandish Painting, 1400–1500 (2004, Yale University Press) and Face to Face: Flanders, Florence, and Renaissance Painting, published by The Huntington on the occasion of this exhibition. Her recent book includes a new essay on the topic and reproduces all of the works included in the display.

The Connection Between Flanders and Florence

Flanders was a wealthy region encompassing parts of present-day Belgium, France, and the Netherlands, and it was ruled by the dukes of Burgundy, whose magnificent court attracted leading artists. These factors led to the flourishing of art and culture in this region. It was in Flanders, argues Nuttall, that in the first decades of the 15th century “a new pictorial language based on the observation of reality” was developed, notably by Jan van Eyck (ca. 1380/90–1441) and Van der Weyden.

Florence also had a prosperous mercantile economy and was an important cultural and artistic center in the 15th century. And since the late Middle Ages, a colony of Florentine merchants and bankers had settled in Flanders to facilitate banking and trade.

Through these commercial connections, Flemish painting became known in Florence, where it was admired for its emotional intensity and awe-inspiring realism. By the end of the 15th century, influential art patrons, including the Medici family, displayed works by Flemish artists in Florentine churches and homes.

The lessons learned from Flemish painting enriched and transformed the art made in Florence. Even Michelangelo commented on the realism of Flemish painting by noting that the painting of Flanders “will cause [the devout] to shed many tears,” and “in Flanders they paint with a view to deceiving the eye.”

A particularly striking example of the impact of Flemish work on a Florentine artist is Hans Memling’s (ca. 1430–1494)

Man of Sorrows Blessing,

an intensely moving Flemish devotional painting that promoted private prayer and the contemplation of Christ’s humanity rather than his divinity. The painting was owned by a Florentine and must have arrived in Florence soon after it was painted, generating a host of copies. Outstanding among these is the copy by Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449–1494) that is so faithful to its model that it was long thought to be by Memling himself. Both works are on view in “Face to Face” for visitors to compare:

Left: Hans Memling, "Man of Sorrows Blessing," ca. 1480-90, oil on panel, 22 x 13 7/8 in. Musei di Strada Nuova, Palazzo Bianco, Genoa. Photo © Musei di Strada Nuova, Genoa. Right: Domenico Ghirlandaio, "The Man of Sorrows Blessing," ca. 1490, tempera on panel, 21 3/8 x 13 1/4 in. Philadelphia Museum of Art, John G. Johnson Collection. Photo courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The Glory of Renaissance Painting

Masterworks gathered together for “Face to Face” include

Memling’s Portrait of a Man with a Coin of the Emperor Nero from the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp

A celebrated cornerstone of Western art, Portrait of a Man with a Coin of the Emperor Nero displays elements typical of Memling’s portraits that were popular with Italians in Flanders, including the fanciful landscape in the background and an especially refined execution. The painting may depict an Italian patron, an idea supported by the Roman coin in his hand.

_-_WGA14926.jpg/445px-Hans_Memling_-_St_John_and_Veronica_Diptych_(right_wing)_-_WGA14926.jpg)

and his Saint Veronica from the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.,

Saint Veronica is a sensitive rendering of the saint kneeling within an expansive landscape and holding a veil imprinted with the image of Christ’s face. This Flemish panel originally formed half of a diptych—with Memling’s Saint John the Baptist, now in Munich—that was owned by Bernardo Bembo, the Venetian ambassador to Burgundy and subsequently the Venetian ambassador to Florence.

as well as Gerard David’s (ca. 1455-1523) Virgin with the Milk Soup from the Palazzo Bianco in Genoa,

An image of intimate domesticity, Virgin with the Milk Soup is a masterful rendering of objects of daily life—including the child’s transparent linen shirt, a basket and prayer book under the window, and the elements of a meal on the table in the foreground—a characteristic of Flemish painting prized by Florentine painters and patrons.

Pietro Perugino’s (ca. 1446/1450–1523) Portrait of Francesco delle Opere from the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence,

and Filippino Lippi’s (ca. 1457–1504) Portrait of a Musician from the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin.

Portrait of a Musician is a remarkable Italian portrait that shows a young man, a bow tucked in his elbow, tuning a lira da braccio (a Renaissance stringed instrument), with other instruments and books on the shelf behind him. The domestic setting, the window with a vista, and virtuosic details in this Italian picture were undoubtedly inspired by Flemish models.

Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449-1494). Left: "Portrait of a Man," ca. 1490, tempera on panel, 20 3/8 x 15 5/8 in. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Right: "Portrait of a Woman," ca. 1490, tempera on panel, 20 3/8 x 15 5/8 in. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens

From a wonderful review:

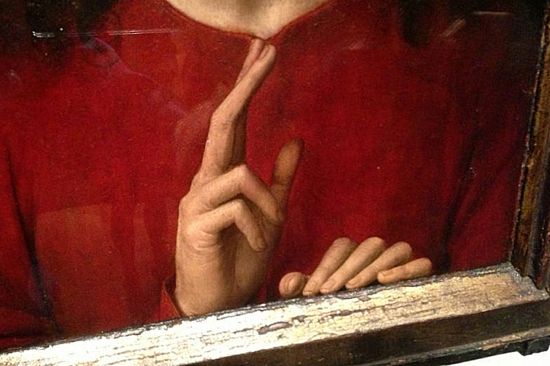

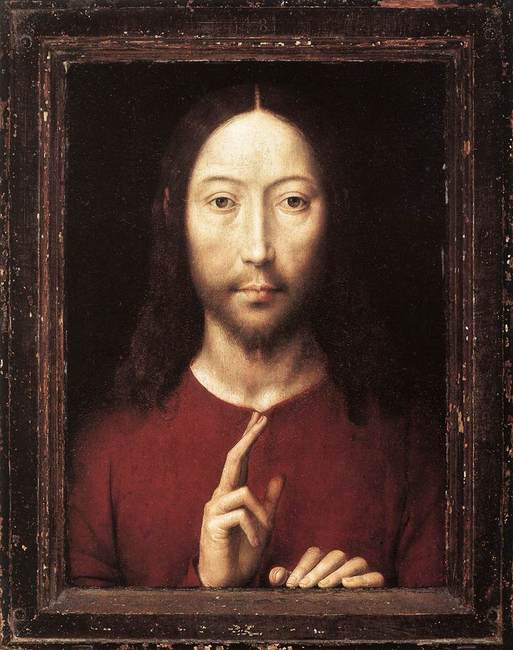

Hans Memling (ca. 1430-1494), "Christ Blessing," 1481

oil on panel, 13 1/8 × 9 7/8 in.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Bequest of William A. Coolidge.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Upon approaching, "Christ Blessing," I was struck by its immense emotional subtlety. The face of Christ has a naturalistic softness that transmits a sense of knowing sadness: It moved and impressed me. But then I lowered my eyes and took in a detail that made the work come even more completely alive: Christ's hand rests on the edge of the frame in a virtuoso display of illusionistic oil painting.

Detail: Hans Memling (ca. 1430-1494), "Christ Blessing," 1481

The image of the hand really got to me: It was an epiphany that alerted me not only to the genius of Memling but also to the "moment" that this show represents. A few short decades before Leonardo completed the, "Mona Lisa," it is clear that his artistic predecessors in the north were doing the hard work that cleared the way for the astonishing presence of his art. The power of that subtle hand -- resting on the edge between illusion and reality -- strikes me as every bit as brilliant and memorable as the, "Mona Lisa," smile. It breaches the barriers between Memling's world and ours and demolishes time...

I was very charmed by Gerard David's, "Virgin With the Milk Soup." Apparently Flemish collectors were too as there are some seven versions of this image which carries iconographic suggestions of salvation and redemption. She is the serene prototype of the window-lit secular beauties that Vermeer would paint two centuries later.

David's, "Virgin," struck me as containing a host of paintings within a painting. His sensitive rendering of the milk soup and bread has the candor of Chardin still life. The tiny vase of flowers on the shelf above the Virgin -- the flowers are meant to denote both sorrow and compassion -- is an image that will bloom into full complexity and become a genre in the hands of later Dutch masters. The gated village scene -- visible through the window -- is like a tiny John Constable landscape.

About the Book

Face to Face: Flanders, Florence, and Renaissance Painting

Written by: Paula Nuttall (Introduction by Catherine Hess)

Available worldwide

Format: Cloth, 96 pages, 8 × 10 inches, 80 color illustrations

ISBN: 978-0-87328-258-1

$29.95

Release: Sept. 2013

Huntington Library Press

This lavishly illustrated catalogue accompanies an exhibition of the same name at The Huntington (Sept. 28, 2013 to Jan. 13, 2014). Co-curator and scholar Paula Nuttall explores the transmission of ideas, techniques, and modes of artistic rendering that first developed in the Burgundian court and became hugely influential in southern Europe—notably on painting in Florence, usually considered the artistic epicenter of Renaissance Europe. Nuttall treats the thematic groupings of the exhibition, exploring the diptych as an art form, the portrayal of the face of Christ, the development of portraiture, and the virtuosic renderings of materials and textures.