November 2017–March 2018

Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, Stanford, California

Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University, Stanford, California

A long-hidden treasure of American art, “Gallery of the Louvre,” will go on view at Reynolda House Museum of American Art in February. The masterpiece of Samuel F. B. Morse, yes that Samuel F. B. Morse, inventor of the telegraph and namesake Morse code, will form the core of a new exhibition: “Samuel F. B. Morse’s ‘Gallery of the Louvre’ and the Art of Invention,” Feb.17 - June 4, 2017. The show will include early telegraph machines from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, 19th-century paintings and prints from Reynolda’s own nationally recognized collection and old master prints from Wake Forest University. Reynolda House is the only venue for this exhibition in the southeastern United States.

Reynolda House Museum of American Art recently pulled back the curtain on two American masterpieces: a monumental painting titled Gallery of the Louvre and the telegraph – both the work of Samuel F. B. Morse. The new exhibition offers a rare look at a historical painting as well as a unique presentation of the diverse talents that made Morse one of America’s first Renaissance men. Samuel F. B Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention is on view at Reynolda House through June 4, 2017.

An Artist With Big Ideas

Morse was an accomplished artist in the early 1800s, noted for his portraiture and large-scale paintings, often in combination. His life-size Marquis de Lafayette, 1825, is installed at New York City Hall. Dying Hercules, 1812, 8 feet x 6 feet, hangs at Yale University Gallery of Art. The even grander 11 feet x 7.5 feet House of Representatives, 1822, is at the National Gallery of Art in Washington.

In 1831, Morse conceived of another large-scale painting, this one to introduce European masterpieces to American audiences decades before the founding of art museums here. His plan was to send the painting on tour to educate the public.

The artist spent months at the Louvre in Paris, painstakingly copying in miniature 38 Renaissance and Baroque masterpieces, including Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, and work by Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Rubens, Tintoretto, Titian, and others. He then ‘installed’ the works in an imagined gallery arrangement on his 6 feet x 9 feet canvas, titling his work, Gallery of the Louvre. Morse paints himself in the center, tutoring a young student as she works on her own copy of one of the masterpieces before her. Morse’s friend, author James Fenimore Cooper, can be glimpsed with his wife and daughter in the left corner.

Gallery of the Louvre was one of Morse’s last paintings. Disheartened when the tour he envisioned did not materialize, Morse turned his attention to a new means of communication: the telegraph. He used wooden canvas stretcher bars from his studio to construct his earliest versions, a selection of which are on loan for the exhibition from Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Worth the Wait

Over the years, Gallery of the Louvre has seldom been exhibited. It was last purchased in 1982, setting a then record for an American work of art. The Terra Foundation, which owns the painting, commenced a national tour in 2015, the much-delayed culmination of the creator’s intent. The installation at Reynolda House Museum is the only venue that has included both of Morse’s greatest creations: Gallery of the Louvre and the telegraph.

The Reynolda House Museum of American Art exhibition of Gallery of the Louvre also includes 19th-century paintings and prints from its renowned collection of American art along with old master prints on loan from Wake Forest University.

The massive six-by-nine foot canvas pictures 38 Renaissance and Baroque masterpieces, which Morse considered to be the finest works inside the Louvre. He painstakingly copied in miniature Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, and work by Caravaggio, Rembrandt, Rubens, Tintoretto, Titian, and other celebrated artists, then imaginatively ‘installed’ the works in the Louvre’s majestic Salon Carré. His arrangement of the old master miniatures within his own painting was done to demonstrate differences in styles and techniques among the artists.

Morse centers himself in the painting’s foreground as an instructor and, figuratively, as a link between European art of the past and America’s cultural future. He is seen tutoring a young art student as she works on her own copy of one of the masterpieces before her. Morse’s good friend, author James Fenimore Cooper, can be glimpsed with his wife and daughter in the left corner.

“Gallery of the Louvre” was a purely academic undertaking for Morse, befitting his role as painting professor and founder of the National Academy in New York. His plan was to send the painting on a national tour after its completion in 1833. When the tour did not materialize, Morse relinquished his creativity to perfecting his telegraph. The painting set a record for an American work of art at the time of its last purchase in 1982: $3.5 million. In 2015, a national tour commenced, the much-delayed culmination of Morse’s original intent.

The show’s final element, early telegraphs, affirms that Morse was an astute bridge between old and new, cleverly moving from painter to inventor. As the Reynolda House Museum of American Art exhibition will show, he used wooden canvas stretcher bars from his studio to construct his earliest versions of the telegraph.

Another highlight of the exhibition will be important works from the collection of Reynolda House Museum of American Art. More than 20 paintings and prints by the 19th century’s leading artists, including William Merritt Chase, Thomas Cole, John Singleton Copley, Edward Hicks, Charles Willson Peale and Gilbert Stuart, serve to explore themes of America’s cultural identity.

Old master prints, among them work by Rembrandt and van Dyck, will be on loan to the exhibition from Wake Forest University’s collection. Prints like these were used in the 17th century in the same way that Morse intended his canvas to instruct and show art two centuries later.

ART

AND RELIGION SECTION

Worthington Whittredge (American, 1820–1910)

The Old Hunting Grounds, 1864

Oil

on canvas

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Gift

of Barbara B. Millhouse, 1976.2.10

Like

Thomas Cole, Worthington Whittredge used nature to evoke the divine. The Old

Hunting Grounds is a complex painting with multiple layers of meaning. The

artist offers the viewer a glimpse of a woodland interior where dappled

sunlight illuminates pale birch trees. A disintegrating birch bark canoe symbolizes

the departure and demise of Native Americans, who were displaced by white

settlers. The arched shape of the framing branches on the sides and at the top

suggests the soaring interior of a Gothic cathedral. For Whittredge, the connection

between forest and cathedral lay in the poetry of his friend William Cullen

Bryant. In “A Forest Hymn,” Bryant wrote that “the groves were God’s first

temples.” Like Samuel Morse, Whittredge served a term as president of the

National Academy of Design, where he shared his views about the connection

between nature and religion with his students.

James Smillie (American, 1807–1885)

after Thomas Cole (English-born American, 1801–1848)

Voyage of Life:

Childhood, Youth, Manhood, and Old Age, 1853–1856

Engravings

on paper

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Gift

of Barbara B. Millhouse, 1983.2.39.a-d

National

Academy of Design co-founder Thomas Cole emigrated from England to America at

the age of seventeen and found his artistic subject in the untrammeled

wilderness of his adopted country, particularly the Hudson River Valley of New

York. The pristine lakes and old-growth forests of the northeast Appalachians

were seen as the ideal classroom for nature painters, who considered it their

duty to capture God’s bountiful creation without distortion. They often

emphasized elements that were symbolic of the brevity of life—sunsets, autumnal

colors, and trees ravaged by storms or the axe.

In

the allegorical series Voyage of Life, the

passage of time and the inevitability of decline are symbolically manifested as

a river of life. Upon initially placid waters, the child is borne on a small

boat with a figurehead holding aloft an hourglass; the boat is filled with

flowers and guided by an angelic steersman. In the second stage, the youth has

abandoned his guardian angel and steers his own course toward castles in the

sky; in the third, the man approaches rapids beneath a storm-threatening sky

haunted by disheartening spirits; in the final image, the world and its time

have receded from the voyager, who gratefully approaches boundless eternity,

received by welcoming angels.

Edward Hicks (American, 1780–1849)

Peaceable Kingdom of the

Branch, 1826–1830

Oil

on canvas

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Gift

of Barbara B. Millhouse, 1969.2.3

Edward

Hicks, sign painter and Quaker minister, found a profound purpose for his art

when the Society of Friends was rocked by internal divisions in the 1820s. Hicks

based his Peaceable Kingdom painting on the prophet Isaiah’s vision of the

hereafter, in which lion, lamb, and other naturally hostile creatures

peacefully co-exist, led by a child holding a sprig of grapes—symbolic of redemption through the blood of Christ. Hicks

imaginatively placed the signing of William Penn’s treaty with the Delaware

Indians beneath the Natural Bridge of Virginia, relating an act of human

reconciliation to a natural marvel that connects two sides of a river gorge.

CLASSICS

SECTION

William Michael Harnett (Irish-born American, 1848–1892)

Job Lot Cheap, 1878

Oil

on canvas

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Original

Purchase Fund from the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation, Z. Smith Reynolds

Foundation, ARCA, and Anne Cannon Forsyth, 1966.2.10

A

crate of used books—a “job lot”—is advertised for cheap sale. Stacked in a

jumble, the books represent English translations of world literature, including

several whose titles are legible—Arabian

Nights, Homer’s Odyssey, and

Dumas’s Forty-Five Guardsmen. The Cyclopaedia Americana, representing

human knowledge to date, is visible in the center.

In

an interview, William Michael Harnett said of his highly realistic still lifes,

“I endeavor to make the composition tell a story.” His works of the 1870s often

combined traditional vanitas elements

suggesting the brevity of life—human skulls, peeled fruit, guttering candles,

extinguished pipes—with a modern symbol of impermanence, the daily newspaper. His

frequent use of books is more ambivalent. Books may quickly pass from “just

published” to “job lot cheap;” on the other hand, like works of art, they may

be passed down for generations, their stories told and retold.

William Rimmer (English-born American,

1816–1879)

Lion in the Arena, circa 1873–1876

Oil

on pressed wood pulp board

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Gift

of Barbara B. Millhouse, 1970.2.2

William

Rimmer found his subjects in ancient history, mythology, and biblical

narratives and returned repeatedly to the contest of gladiator and lion, recalling

Hercules’s first labor, killing the Nemean lion. The story enabled Rimmer to

demonstrate his mastery of anatomy, which he practiced both as a physician and professor

of art, which he taught at Harvard University and the National Academy of Design

soon after Samuel Morse stepped down as president.

Lion in the Arena thrusts the viewer into

the midst of a tense stand-off, in which both man and beast crouch, coiled with

fear and bloody determination. In the middle ground, further scenes of mortal

combat play out—a rearing lion bites into a man’s shoulder, another lion lies

bloodied, and sprinting gladiators kick up dust, obscuring the cheering crowds

of the Coliseum.

William Merritt Chase (American,1849–1916)

In the Studio, circa 1884

Oil

on canvas

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Original

Purchase Fund from the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation, Z. Smith Reynolds

Foundation, ARCA, and Anne Cannon Forsyth, 1967.2.4

A

fair-haired sitter in a French neoclassical gown looks up from her study of a

print, surrounded by a veritable library of fine and decorative arts gathered

during William Merritt Chase’s many travels. The American Impressionist’s famously

lavish studio in New York’s Tenth Street Studio Building recalls a description

of Gilbert Osmond’s apartment in Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady, published in 1881:

It was moreover a seat of ease, indeed of

luxury, telling of arrangements subtly studied and refinements frankly

proclaimed, and containing a variety of those faded hangings of damask and

tapestry, those chests and cabinets of carved and time-polished oak, those

angular specimens of pictorial art in frames as pedantically primitive, those

perverse-looking relics of mediæval brass and pottery, of which Italy has long

been the not quite exhausted storehouse.

Chase

achieved fame as an artist, a teacher, and a cosmopolitan cultural figure who once

exclaimed “My God, I’d rather go to Europe than to Heaven!”

Robert Ingersoll Aitken (American, 1878–1949)

A Thing of Beauty, circa 1910

Bronze

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Gift

of Richard Earl Johnson, 2008.4.1

Though

born a generation after the decline of Federal Era classicism, Robert Aitken remained

committed to an academic conservatism throughout a career that took him from

San Francisco to Paris and New York. This graceful bronze nude, whose title is

borrowed from a line of Keats’s poetry (“A thing of beauty is a joy forever”),

is a study in classical idealism and contrapuntal poise; legs, arms, and

fingers intertwine, yet the figure appears perfectly balanced.

In

1929, Aitken was appointed vice-president of the National Academy of Design,

founded over a century earlier by Samuel Morse. When a dedicated Supreme Court

building was constructed in the 1930s, Aitken designed the sculptural group on

the west pediment, above the main public entrance. Years earlier, Morse’s first

inter-city telegram was sent from the Supreme Court chamber when it was still

located within the Capitol; Morse would spend many years defending his

intellectual property before the Court.

ART

AND DEMOCRACY SECTION

Jeremiah Thëus (Swiss-born American, 1716–1774)

Mrs. Thomas Lynch, 1755

Oil

on canvas

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Gift

of Barbara B. Millhouse, 1972.2.1

Jeremiah

Thëus’ likeness of Elizabeth Allston Lynch is the oldest piece in Reynolda’s collection

and is an excellent example of colonial portraiture. She was born into the

prominent Allston family in South Carolina and married into the Lynch family,

also notable citizens. Her husband, Thomas Lynch, was a delegate to the

Continental Congress from 1774 to 1776, and her son, Thomas Lynch, Jr., signed

the Declaration of Independence.

As

a young man, Samuel Morse believed that the Revolution had ushered in a new age

of peace and prosperity. The successes after the Revolution—increased wealth and

leisure, more widespread knowledge, and new inventions—were evidence of

America’s exceptionalism and proof that the democratic experiment would thrive.

In later years, Morse became antagonistic toward the nation’s rising pluralism.

John Singleton Copley (American, 1738–1815)

John Spooner, 1763

Oil

on canvas

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Bequest

of Nancy Susan Reynolds, 1968.2.1

In

contrast to the patriotic Lynch family, the subject of this portrait, John Spooner, remained loyal to the

English crown in the years leading up to the Revolution. He shared those

sentiments with his portraitist, John Singleton Copley. Copley made a living

taking commissions for portraits but had strong ambitions to paint great scenes

of history. Eventually, he left the colonies for England for both artistic and

political reasons; Spooner had fled to England six years earlier.

More

than a generation younger than Copley, Samuel Morse also traveled to England,

but for artistic training only and with no intent to make it his permanent

home. When Morse arrived in London in 1811, he took rooms near Copley. By then,

the elder artist had achieved some success, having been elected to the Royal

Academy in 1779. The story of the transatlantic pilgrimage of American artists

to London demonstrates the close cultural ties between England and America

during the colonial and federal periods, even when political ties were

threatened or severed. Morse would soon find those ties imperiled again by the

War of 1812.

Christian Inger (German-born American, circa

1814–circa 1895)

after

Emanuel Leutze (German-born American,1816–1868)

Washington Crossing the

Delaware,

1866

Hand-colored

lithograph

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Gift

of Barbara B. Millhouse, 1983.2.40

On

a densely snowy Christmas night, outnumbered patriot forces embarked upon a

surprise attack against Hessian troops (German soldiers employed by the

British) in Trenton, New Jersey. The German-born American artist Emanuel Leutze

immortalized the battle with some invention. Winding through an icy river lit

by a rising winter sun, General Washington’s tiny craft in this image is packed

with famous patriots: future president James Monroe, who was not present for

the battle, holds a flag that Betsy Ross had yet to design; second-in-command

Nathanael Greene leans out of the vessel; and General Edward Hand holds tight

to his tricorn hat. At Washington’s knee sit a Scottish immigrant, identifiable

by his bonnet, and a patriot of African descent named Prince Whipple. Other

soldiers embody types that soon would become Americans: farmers, frontiersmen,

and, in the stern, a Native American.

Leutze

painted several monumental versions of the crossing. One was destroyed in Germany

by Allied bombers in World War II;

another painted in 1851 today fills a twelve-by-twenty-one foot wall in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. This engraving was made in 1866 and further established the fame of this image of a cold and beleaguered revolutionary crew on a crossing to unexpected victory.

another painted in 1851 today fills a twelve-by-twenty-one foot wall in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. This engraving was made in 1866 and further established the fame of this image of a cold and beleaguered revolutionary crew on a crossing to unexpected victory.

Edward Savage (American, 1761–1817)

after

Robert Edge Pine (English,1742–1788)

Congress Voting

Independence,

restrike 1906, from 1801–1817 plate

Stipple

and line engraving from unfinished plate

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Gift

of Barbara B. Millhouse, 1983.2.35

In

Robert Edge Pine’s interpretation of Congress

Voting Independence, Thomas Jefferson stands at the literal and symbolic

epicenter of a political earthquake—the delivery of the Declaration of

Independence in the State House (Independence Hall, Philadelphia) in 1776. A seated

John Hancock receives the document while a pensive Benjamin Franklin, in the

foreground, rests with chin in hand. Franklin was a major figure in the American

Enlightenment, a movement whose followers found scientific advances and

political liberty to be mutually dependent. Franklin’s discoveries in the field

of electricity were foundational for many practical inventions of the next century,

including Morse’s telegraph. Franklin believed that “Men who invent new Trades,

Arts or Manufactures…may be properly called Fathers of their Nation.”

Robert

Edge Pine was an Englishman sympathetic to the American revolutionaries, and

made portraits of Washington and others in a room within the State House,

leading historians to consider

this image the most accurate visual account of the vote for independence. The American painter and printmaker Edward Savage created an engraving of the painting, and prints were made from the engraving as late as 1906.

this image the most accurate visual account of the vote for independence. The American painter and printmaker Edward Savage created an engraving of the painting, and prints were made from the engraving as late as 1906.

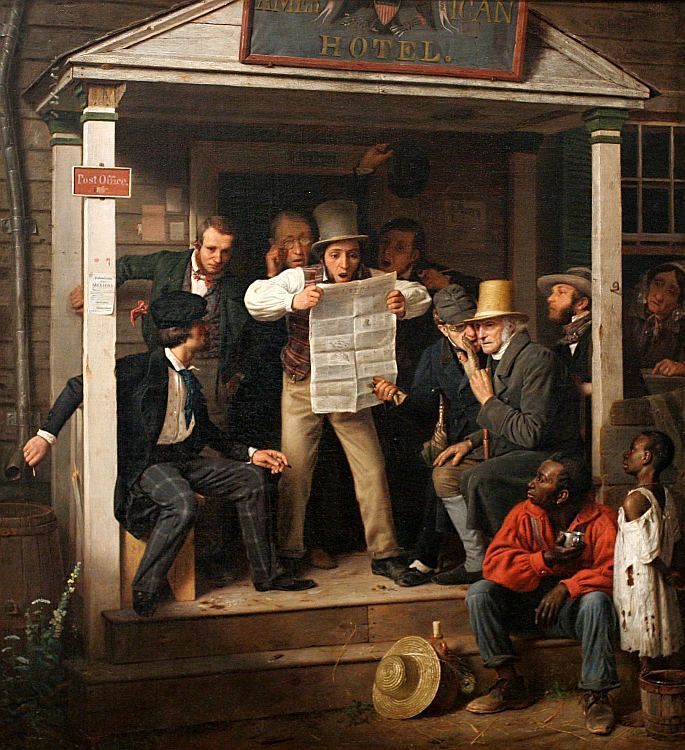

John Sartain (English-born American,1808–1897)

after

George Caleb Bingham (American, 1811–1879)

The County Election, 1854

Hand-colored

engraving with glazes

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Gift

of Barbara B. Millhouse, 1983.2.37

Beneath

a banner proclaiming “The Will of the People the Supreme Law,” the messy drama

of democracy rollicks a small American town. Candidates tip their top hats,

while men argue the merits of their platforms; a drunk voter is carried to cast

his vote, having been served by an African American who is ineligible to vote;

children play mumble-the-peg, a game in which, like politics, advantage is

quickly gained or lost; thoughtful citizens read national newspapers near a

downcast man who was literally bruised by political controversy.

Artist

and state legislator George Caleb Bingham had two favorite subjects: frontier

life on the Missouri River and the democratic process.

Painted in 1851–1852 and engraved in 1854, at the height of national contention over slavery, The County Election contains a hint about the artist’s sympathies: a sign for the “Union Hotel” stands like a beacon of permanence for a nation at a time of explosive division. Bingham tipped his own hat: “I design [the work] to be as national as possible—applicable alike to every Section of the Union.”

Painted in 1851–1852 and engraved in 1854, at the height of national contention over slavery, The County Election contains a hint about the artist’s sympathies: a sign for the “Union Hotel” stands like a beacon of permanence for a nation at a time of explosive division. Bingham tipped his own hat: “I design [the work] to be as national as possible—applicable alike to every Section of the Union.”

PORTRAITURE

SECTION

Gilbert Stuart (American, 1755–1828)

Mrs. Harrison Gray Otis (Sally Foster), 1809

Oil on

mahogany panel

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Original

Purchase Fund from the Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation, Z. Smith Reynolds

Foundation, ARCA, and Anne Cannon Forsyth, 1967.2.3

Sally

Foster Otis, married to the president of the Massachusetts state senate, was

already a mother of ten when, dressed in a highly-fashionable neo-Grecian gown,

she sat for Gilbert Stuart in Boston. In her large home on Beacon Hill, she

commanded a social circle that supported her husband’s ambitions as congressman,

senator, mayor, and, eventually, leader of the Federalist Party. One encounter was

reported by former president John Adams: “I never before knew Mrs. Otis. She

has good Understanding. I have seldom if ever passed a more sociable day.”

Gilbert

Stuart once advised the young Samuel Morse to “Be rather pointed than fuzzy…you

cannot be too particular in what you do to see what sort of an animal you are

putting down.” Morse revered Stuart, and considered himself fortunate to earn

forty dollars less per painting than the elder artist. It is difficult to

overstate Stuart’s accomplishments; he portrayed the nation’s first five

presidents and nearly every major figure in the political and social life of

the early republic. Nonetheless his life was highly peripatetic, fleeing

creditors, quarrels, and bankruptcies from one metropolis to another.

Charles Willson Peale (American, 1741–1827)

Mr. and Mrs. Alexander

Robinson,

1795

Oil

on canvas

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Gift

of Barbara B. Millhouse, 1973.2.2

The

Robinsons were newly married and expecting their first child when the bride’s

famous father, Charles Willson Peale, painted this double portrait. The happy occasion

was marred by what Peale called Alexander’s “bad grace” during the sitting.

Robinson, a wealthy immigrant from Ireland, was described as haughty, proud,

and disdainful of the painting profession; he reportedly dismissed Peale as a

“showman.” Whatever discord was felt, the resulting portrait is a tribute to

companionable marriage—two people on the same plane, holding hands—and, unlike most

double portraits, it is the wife who meets our gaze, intimately and with

sparkling intelligence.

Like

Samuel Morse, Charles Willson Peale studied painting with Benjamin West in

London and pursued dual paths of art and science. Peale founded the nation’s

first natural history museum in his own home, where he displayed the skeleton

of a mastodon he had excavated. Later the museum moved to the State House

(Independence Hall) in Philadelphia.

Thomas Sully (English-born American,

1783–1872)

Jared Sparks, 1831

Oil

on canvas mounted on panel

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Gift

of Barbara B. Millhouse, 1984.2.11

A

dashing young man of literary bent is depicted with a finger marking his place

in a text—a common trope employed by artists in the Italian and Northern

Renaissance. Historian Jared Sparks richly deserved this scholarly

immortalization; in 1830, he had completed compiling and editing a

twelve-volume series entitled The

Diplomatic Correspondence of the American Revolution. Sparks would become

the seventeenth president of Harvard University.

Like

Samuel Morse, Thomas Sully studied with Benjamin West at the Royal Academy in

London, and developed a network of mutually supportive artists, arranging for

exhibitions and commissions to copy one another’s work. They competed for the

prestigious commission for the City Hall in New York to paint the Marquis de

Lafayette, which Morse won in 1825. But following the deaths of Charles Willson

Peale and Gilbert Stuart in 1827 and 1828, respectively, Sully became the

preeminent figure in American portraiture.

Emmanuel Gottlieb Leutze (German-born American, 1816–1868)

Worthington Whittredge

in His Tenth Street Studio, 1865

Oil

on canvas

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Gift

of Barbara B. Millhouse, 1984.2.12

The

Tenth Street Studio Building, on West 10th Street between 5th

and 6th Avenues in Manhattan, was home to many of the great names of

American art, including Winslow Homer, Frederic Edwin Church, Albert Bierstadt,

Martin Johnson Heade, William Merritt Chase, Emanuel Leutze, and Worthington

Whittredge. Designed by Richard Morris Hunt, the building’s proximity to New

York University and Washington Square Park, where Samuel Morse kept his studio,

helped to establish Greenwich Village as the center of the New York art world.

The

studios themselves provided a wealth of subjects for artists, as seen in

Chase’s painting In the Studio and

Leutze’s Worthington Whittredge in His

Tenth Street Studio. Whittredge’s erect posture and noble profile made him

a convenient model for Leutze’s masterwork, Washington

Crossing the Delaware.

MAPPING

THE AMERICAS SECTION

Edward Savage (American, 1761–1817)

The Washington Family, 1798

Stipple

engraving

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Gift

of Barbara B. Millhouse, 1983.2.34

Edward

Savage specialized in portraits of influential Americans of the Revolutionary

generation, including Jedidiah and Sarah Morse, parents of Samuel. On

commission from Harvard University, Savage painted the newly elected President

Washington in 1789, along with portraits of Martha Washington and her

grandchildren, Eleanor Parke Custis and George Washington Parke Custis. Savage

combined his individual portraits into this family grouping as both a painting and a print. Attended by an enslaved house servant, possibly William Lee or

Christopher Shields, the family is surrounded by symbols of national ambitions:

young George rests calipers on a geographical globe, representing the young

nation’s global ambitions, as the others unroll plans for the newly designed

federal city of Washington, D.C. The plans are held in place by the president’s

resting sword.

Presenting

the print to Washington in 1798, Savage wrote, “The likenesses of the young

people are not much like what they are at present. The Copper-plate was begun

and half finished from the likenesses which I painted in New York in the year

1789…The portraits of yourself and Mrs. Washington are generally thought to be

likenesses.”

Henry S. Tanner (American, 1786–1858)

A Map of North America,

Constructed According to the Latest Information (in four parts), 1822

Hand-colored

engraving on woven paper

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Courtesy

of Barbara B. Millhouse, IL2003.1.34d

Henry

S. Tanner’s New American Atlas of

1822 included a large map of the continent, which reflected many discoveries

made after Jedidiah Morse’s influential maps of the previous century, including

the findings of the 1804–1806 Lewis and Clark expedition to the Pacific Ocean

following the Louisiana Purchase. The map’s southwest quadrant includes a

graphic cartouche that provided views of Niagara Falls and the Natural Bridge

that were borrowed by the Quaker artist Edward Hicks (see his

Falls of Niagara in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

and his Peaceable Kingdom of the Branch in this exhibition).

Falls of Niagara in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

and his Peaceable Kingdom of the Branch in this exhibition).

David Johnson (American, 1827–1908)

Natural Bridge,

Virginia,

1860

Oil

on canvas

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Gift

of R. Philip Hanes in honor of Charles H. Babcock, Sr., 1968.2.2

New

York artist David Johnson was a member of the second generation of Hudson River

School painters. His rigorously realistic landscapes were imbued with a

romantic sensibility, often evident in the locations he selected. Nineteenth-century

landscape painters made pilgrimages to spectacular natural wonders such as Niagara

Falls and the Natural Bridge in Virginia, which Johnson visited in 1860 to

create this view.

The

exactness of Johnson’s pictorial description echoes a description by Thomas

Jefferson, who bought the Natural Bridge from King George III in 1774.

Jefferson’s geological analysis concludes with several exclamations: “It is

impossible for the emotions arising from the sublime to be felt beyond what

they are here; so beautiful an arch, so elevated, so light, and springing as it

were up to heaven! The rapture of the spectator is really indescribable!”

Martin Johnson Heade (American, 1819–1904)

Orchid with Two

Hummingbirds, 1871

Oil

on prepared panel

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Museum

Purchase, 1976.2.8

In

the upper branches of the Brazilian rainforest, a gemlike Phaon Comet

hummingbird and a Brazilian Fairy hummingbird seem to greet one another beside

a gleaming Cattleya orchid. Martin Johnson Heade excelled in precise yet

romantic nature studies that captured the changing effects of light,

atmosphere, and storms. His trips to Brazil were inspired by the geographical

writings of the German naturalist-explorer Alexander von Humboldt, whose descriptions

of tropical light challenged painters like Heade and Frederic Edwin Church.

“The sun does not merely enlighten,” Humboldt wrote. “It colors the objects,

and wraps them in a thin vapor, which, without changing the transparency of the

air, renders its tints more harmonious, softens the effects of the light, and diffuses

over nature a placid calm, which is reflected in our souls.”

Humboldt’s

Cosmos, a magnum opus subtitled “A Sketch of a Physical Description of the

Universe,” inspired a generation of painters and scientists. But Humboldt was

inspired in turn by witnessing Samuel Morse at work on his condensed cosmos of

European painting, Gallery of the Louvre.

Humboldt spent days observing Morse at work, and the two strolled the Louvre

discussing its marvels. The acquaintance would be renewed when Humboldt

supported the adoption of Morse’s system of telegraphy in Europe.

Alfred Jones (English-born American,1819–1900)

after Richard Caton Woodville, Sr. (American,

1825–1855)

Mexican News, 1851

Hand-colored

engraving

Reynolda

House Museum of American Art

Gift

of Barbara B. Millhouse, 1983.2.36

In

his brief, restless life, Richard Caton Woodville achieved wide recognition

through prints made after his paintings, which typically focused on closely

observed scenes of everyday life. In this work, citizens of an unidentified

small town respond to the latest news from the Mexican-American War (1846–1848),

in which the United States stood to gain vast territories, including the future

states of California, Utah, Nevada, New Mexico, Arizona, and part of Colorado. Also

at stake in the war was the legality of slavery in the new territories. Outside

the protective porch of the American Hotel, an African American father and

daughter listen attentively to the news; neither they nor the woman listening

from an adjacent window have a political voice as voters, yet the image

suggests that they feel political winds just as keenly.

Within

just a few years of the 1844 demonstration of the telegraph, two giant

enterprises developed that would shape American life for many decades. The

Western Union Telegraph Company was formed as the nation’s first industrial

monopoly, combining communications interests from New England to the

Mississippi Valley. And in 1846 five daily newspapers in New York agreed to

share costs of transmitting news of the Mexican-American War by telegraph, thus

forming the Associated Press.