Museum of Fine Arts, BostonApril 9 to July 9, 2017

Royal Academy of Arts, London

August 5 to November 12, 2017

Matisse in the Studio is the first major international exhibition to examine the roles that objects from the artist’s personal collection played in his art, demonstrating their profound influence on his creative choices. Henri Matisse (1869–1954) believed that these objects were instrumental, serving both as inspiration and as a material extension of his working process. In 1951, he described them as actors: “A good actor can have a part in ten different plays; an object can play a role in ten different pictures.”

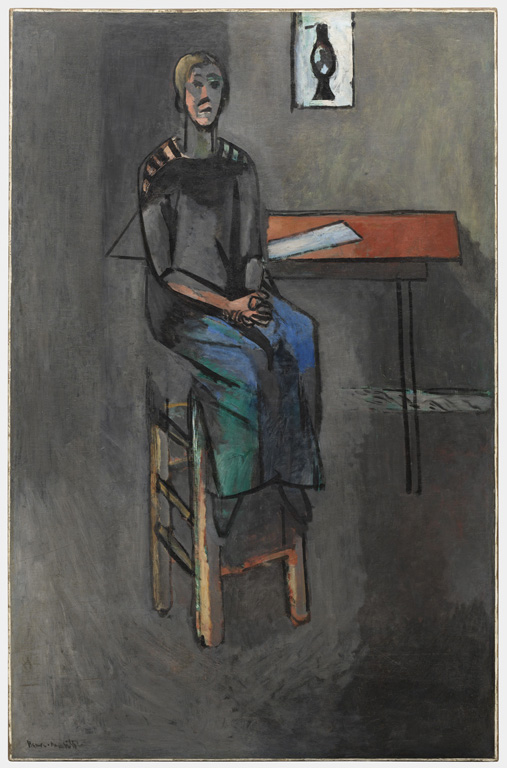

Henri Matisse (French, 1869–1954), Interior with an Etruscan Vase, 1940. Oil on canvas. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland. Gift of the Hanna Fund. Courtesy of The Cleveland Museum of Art © 2017 Succession H. Matisse / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The exhibition presents a selection of major works by Matisse from different periods of his career—including approximately 34 paintings, 26 drawings, 11 bronzes, seven cut-outs and three prints, and an illustrated book. The artworks are showcased alongside about 39 objects that the artist kept in his studios—many on loan from the Musée Matisse, Nice, as well as private collections—and publicly exhibited outside of France for the first time. They include a pewter jug, a chocolate maker given as a wedding present and an Andalusian vase found in Spain, as well as textiles, sculptures and masks from the various Islamic, Asian and African traditions that Matisse admired.

On view at the MFA from April 9 to July 9, 2017 in the Ann and Graham Gund Gallery, Matisse in the Studio travels to the Royal Academy of Arts in London from August 5 to November 12, 2017. An illustrated catalogue, produced by MFA Publications, accompanies the exhibition with contributions by renowned Matisse scholars. The exhibition is organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Royal Academy of Arts, in partnership with the Musée Matisse, Nice.

The exhibition was co-curated by Helen Burnham, Pamela and Peter Voss Curator of Prints and Drawings at the MFA; Ann Dumas, Curator of the Royal Academy of Arts; and Ellen McBreen, Associate Professor of Art History at Wheaton College and a prominent Matisse scholar.

“Matisse in the Studio offers the rare opportunity to observe the workings of a great artist’s mind. We are thrilled to be able to display so many objects from Matisse’s own collection and demonstrate their central importance to his creative process,” said Burnham.

Henri Matisse was one of the great artists of the 20th century, known for his extraordinary approach to color and composition. Born in Northern France, he studied in Paris and moved frequently during his long career, bringing his personal collection of objects with him from studio to studio, and eventually settling in Nice, in the South of France. While Matisse’s enormous impact on Modern art has been widely acknowledged, his sustained interest in the art of cultures outside of the French tradition in which he was raised has been little explored.

As Matisse stated, he did not paint an object so much as the emotion that it stirred in him. Exploring the various ideas and inspirations that the artist drew from his collection of objects, the exhibition is organized into five thematic sections: “The Object Is An Actor,” “The Nude and African Art,” “The Face,” “Studio as Theatre” and “Essential Forms.”

“The exhibition tells the story of Matisse’s lifelong engagement with African, North African and Asian cultures. Viewers will see Matisse in a new light, since these artistic borrowings raise so many relevant questions about how we continue to engage with cultural difference today,” said McBreen.

The Object Is an Actor

The exhibition’s introductory section focuses on a few frequent objects or “actors” that frequently reappear under various guises in several works spanning four decades of Matisse’s career. A 1946 photograph by Hélène Adant shows some of Matisse’s favorite objects, lined up in a row. On the back, an inscription by the artist reads, “Objects which have been of use to me nearly all my life.” A green glass Andalusian vase (early 20th century, Musée Matisse, Nice), which was purchased by the artist during a 1910–11 trip to Spain, can be seen in the middle of the photograph; the object itself is displayed in the gallery.

The anthropomorphic vase takes center stage in the still lifes

Vase of Flowers (1924, MFA Boston)

and Safrano Roses at the Window (1925, Private Collection) (Right , above).

Matisse faithfully recreated the vase’s physical qualities in both paintings, but adapted its shapes and colors. This pair of works reveals his interest in the environments that objects can create—in each painting, the vase is surrounded by a particular space and light, as well as by other neighboring objects—changing how viewers perceive it.

In 1898, when Matisse married Amélie Parayre, he received a silver chocolate pot (19th century, Musée Matisse, Nice) as a wedding gift from his friend and fellow artist Albert Marquet. It appears in the company of other objects in numerous still lifes and drawings, including the never-before-exhibited watercolor Still Life and Heron Studies (about 1900, Private Collection).

The exceptional Bouquet of Flowers in a Chocolate Pot (1902, Musée Picasso, Paris), also featured in this section, was purchased in 1939 by Picasso, Matisse’s friend and artistic rival.

The Nude and African Art

This section focuses on ideas that Matisse borrowed from a wide variety of objects depicting the human figure. Around 1906, when he started collecting figures and masks from Africa, Matisse radically changed the composition and handling of the body in his work, developing a new mode of representation at odds with long-standing academic principles and social conventions.

The first African sculpture acquired by Matisse was a Vili figure from Congo (19th-early 20th century, Private Collection), purchased at a Parisian shop in the fall of 1906. He painted the Vili sculpture only once, in Still Life with African Statuette (1907), a rarely exhibited work from a private collection.

Standing Nude (1906–07, Tate Modern) is among the first major paintings to demonstrate a later, more specific response to the art of Africa, in the context of a larger early 20th-century fascination with ideas from cultures beyond the Western canon. Combining ideas from a nude photograph in a popular French illustrated journal with abstract elements borrowed from African sculpture, the painting is one of the more challenging nudes of 20th-century art.

Another work from the same time period, Still Life with Plaster Figure (1906, Yale University Art Gallery), shows an uncast version of Matisse’s bronze sculpture Standing Nude (1906, Private Collection), one of the first sculptures that he radically simplified and modified for expressive effect.

The bronze sculpture Reclining Nude I (1907, Collection of the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York) appears in a number of works in the show, including Goldfish and Sculpture (1912, Museum of Modern Art, New York), where it is juxtaposed with a vase against a rich blue background.

A later painting, Woman on a High Stool (1914, Museum of Modern Art, New York) demonstrates an even more direct use of powerful elements commonly seen in African art, including a rigorous posture, elongated torso and ovoid face—emulating the forms and mood of a Fang reliquary figure from Guinea (19th-early 20th century, Private Collection) that Matisse owned.

A painting of the same year, Seated Figure with Violet Stockings (1914, The Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation Collection) features a similarly haunting woman. Matisse scratched the surface of the painting in a frenzied manner, covering the figure’s face with varied strokes that both negate her individual character, but strengthen her intensity, raising questions about the complex ways Matisse treats gender in his work.

The Face

Matisse also developed a new visual language for portraiture. Paintings and sculptures in this section reveal a shift in priority, to capture the character of his sitters rather than their physical likenesses. This new approach was strongly influenced by his collection of masks, including examples from the Punu, Yoruba and Kuba cultures of Africa. While Matisse, like many of his contemporaries, knew little about the masks’ histories, users or original contexts, he appropriated from their forms and functions, using them to illuminate otherwise unseen qualities of the wearer.

The stark simplicity of Matisse’s portrait Marguerite (1906–07, Musée Picasso, Paris) evokes the innocence of childhood that his daughter, 13 years old at the time, is poised to leave behind. Marguerite’s flattened features, including a profile nose positioned on a frontal face, are thickly outlined. Her face is separated from her neck, like a mask, by a crisp black band—a representation of the ribbon she wore to cover a tracheotomy scar. In the fall of 1907, when Matisse and Picasso exchanged artworks, Picasso chose this portrait and placed it on his studio wall near a mask by a Punu artist from Gabon, suggesting that he may have seen a connection.

A rare Self-Portrait (1906, Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen)—one of four painted by Matisse over the course of his life—takes on a sculptural quality, as if he had roughly modeled his likeness rather than painted it. The painting lacks the narrative details present in Matisse’s earlier self-representations, such as a brush, an easel, studio surroundings and his eyeglasses—all of which emphasized his identity as an artist. Instead, this self-portrait draws focus to the expressive identity of Matisse’s fixed gaze, emerging from eyes roughly rendered in brown and blue contours.

Matisse’s Jeannette series of five sculptures reveals him exploring various personifications of the same model, Jeanne Vaderin, and emphasizing different aspects of her character. Three sculptures—Head of Jeannette I (1910, cast 1953), Head of Jeannette III (1911, cast 1966) and Head of Jeannette V (1913, cast 1954), all from the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, show Matisse progressively moving from a naturalistic portrait to a stripped-down essence of the model.

This section also introduces another model, Lorette, whom Matisse met in 1916. In

The Italian Woman (1916, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York), Lorette’s black, staring, yet inwardly focused eyes and heavy brow contribute to a mask-like countenance. Her long black hair both separates her figure from the background and joins her to it—evoking the idea of veiling and unveiling.

Over the course of a year, Lorette appeared in nearly 50 of Matisse’s paintings, transformed through various costumes and poses.

Lorette with a Cup of Coffee (1917, Art Institute of Chicago) shows a close-up view, seen from above. The checkerboard pattern of a small hexagonal wooden table with a mother-of-pearl inlay (early 20th century, Musée Matisse, Nice), likely of Tunisian origin, is visible in the lower right of the painting. The visual similarities of the model and the table—both painted with cool silver-whites, dark browns and blacks—compress the space of the intimate painting.

In later works from the 1920s, the complex patterns from Matisse’s objects would not just complement figures, but also provide the overall frame through which figures are seen and, in some cases, structure the entire composition.

Studio as Theatre

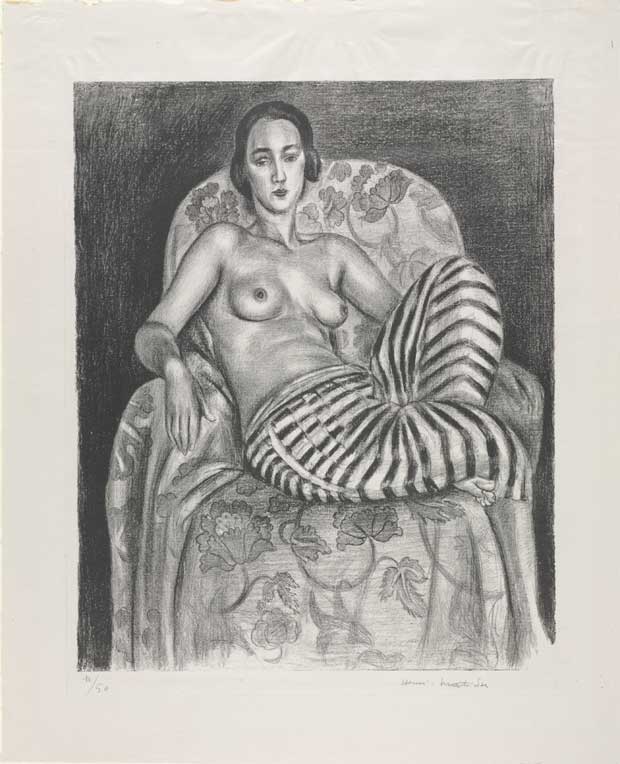

In the 1920s, while working in Nice, Matisse began to paint a series of interiors, often featuring a French model placed against a decorative, richly patterned background and performing the role of a North African “odalisque”—an outdated term with sexist overtones, used to describe a female concubine in a harem. The artist’s working space in his apartment at Place Charles–Félix was like a theater set, continuously staged and redesigned with elaborate props and textiles, many from the Islamic world. While Matisse had seen Islamic interiors firsthand during previous travels to Spain and Morocco, many of his objects that defined his 1920s interiors—largely from North Africa—were acquired in France. This section explores the complex fictions he created from North African culture, as well as the implications of those ideas for viewers today.

Matisse owned half a dozen haitis—pierced and appliquéd cotton textiles of North African origin (often referred to as moucharabiehs after the fretwork wood or stucco screens that are their closest architectural counterparts in Islamic design). A blue-green example with two arched panels from North Africa (early 19th-early 20th century, Private Collection) makes an appearance in

The Moorish Screen (1921, Philadelphia Museum of Art) as a dominant motif in a collage of richly decorative patterns that also includes rugs and wallpaper. The haiti potentially reads as a solid tiled wall, blocking the viewer’s understanding of the rest of the architecture by hiding the juncture where two walls would logically meet. Two models in ethereal white dresses are pitted against the profusion of decorative surfaces, challenging the tradition of primary focus on the human figure within an intimate genre scene.

Matisse similarly plays with the spatial relationship between figure and background in

Reclining Odalisque (1926, Metropolitan Museum of Art), where he diffuses the gaze away from the model, Henriette Darricarrère, by surrounding her with a rich ornament of patterns and colors. A large textile with a floral pattern abruptly transitions into the abstract patterns of Matisse’s large red haiti (late 19th–early 20th century), such that every part of the surface is an extension of another.

Purple Robe with Anemones (1937, Baltimore Museum of Art) also implies an exchange of energy between the model and the objects that surround her, including a pewter jug (late 18th century, Musée Matisse, Nice) filled with flowers and a small painted table, likely from Algeria (early 20th century, Musée Matisse, Nice). The curved lines on the jug relate directly to the wavy lines on the woman’s dress and on the wall behind her, while the floral forms on her skirt are echoed in the chair and the table.

Several of Matisse’s paintings and works on paper, beginning in 1928, depict an elaborately painted octagonal wooden chair (19th century, Musée Matisse, Nice), likely of Algerian or Moroccan origin. Its arms and supports are often represented as an extension of the model lounging in it.

In the drawing Seated Odalisque and Sketch (1931, Baltimore Museum of Art), the model’s raised and bent legs mirror the arcade opening between the legs of the chair just behind her.

Another drawing, Lisette in a Turkish Chair (1931, Centre Pompidou) shows the model’s extended leg emerging from where viewers might expect to find the leg of the chair, to which her forms have been melded.

In Odalisque on a Turkish Chair (1928, Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris), Matisse further explores these poetic connections between bodies and objects in paint. He uses flesh-like pink tones for the chair’s brown wooden frame, so that the model’s right arm forms a continuous V with one of the chair’s spindles, which seems to rise from her elbow as if they were connected. Here, the painted floral decoration of the original chair has been removed to focus attention on the structural parallels with the model’s body. These patterns migrate to other surfaces, however, like the hanging fabric, embroidered vest and belt, chessboard and blue-and-white vase, so that the entire painting takes on the decorative qualities of the chair.

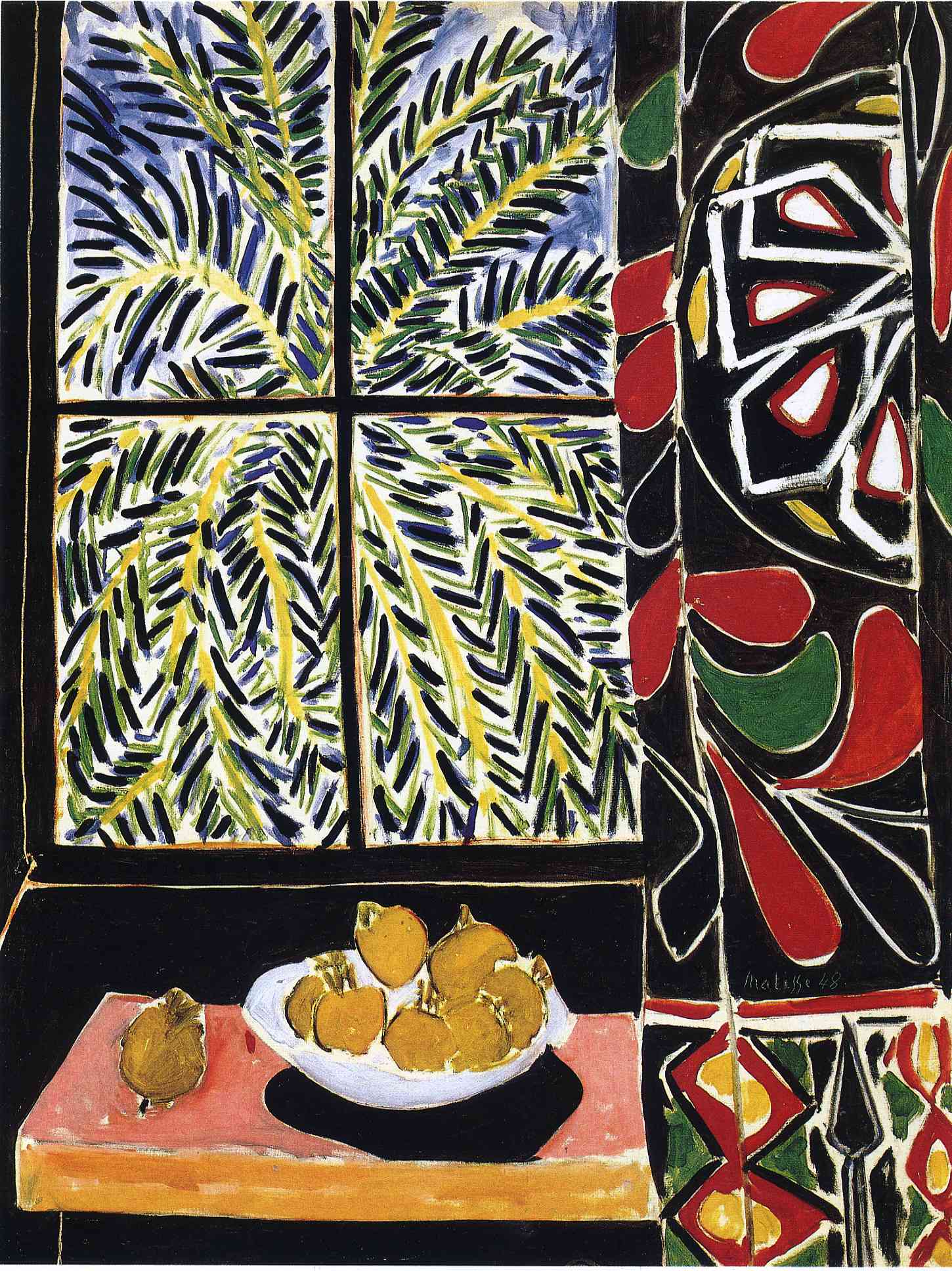

This section also includes one of Matisse’s last great canvasses,

Interior with Egyptian Curtain (1948, The Phillips Collection), in the company of the actual Egyptian khayamiya, made by a tentmaker in Cairo, that is featured in it. This display is a powerful demonstration of the exhibition’s theme: that Matisse did not simply replicate the objects in his collection; instead, he was inspired by decorative traditions for the distinctive ways of seeing and making that they offered him.

Essential Forms

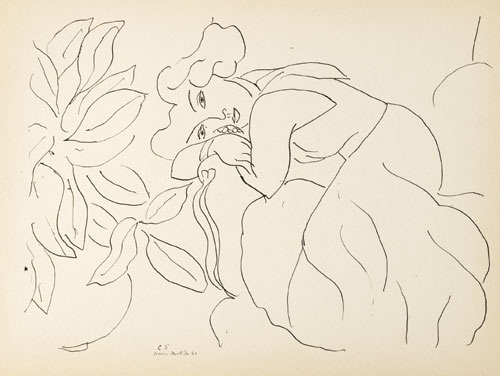

During the mid-1930s, Matisse’s art underwent a radical transformation, in which drawing played a crucial role. He began rendering people and objects in a visual shorthand that made them seem to float within the abstract space of the paper. Employing an increasingly linear and graphic pictorial language, Matisse’s imagery gradually transformed into ensembles of distilled pictorial signs for the things represented.

In late 1941 and early 1942, Matisse created a series of drawings—most of women, often represented in conjunction with floral motifs—that were later published in a large portfolio,

Henri Matisse: Themes and Variations. The portfolio consists of 17 themes, each of which is designated by a letter of the alphabet and followed by numbered variations. A variation from the G theme (1941, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem) is on view in the exhibition, showing an example of Matisse’s developing graphic shorthand for objects.

A few months after finishing the Themes and Variations drawings, Matisse began to work seriously with cut-and-pasted paper as an independent medium. His first extended cut-out project was an illustrated book called Jazz, published in 1947. For Matisse, the process of making cut-outs, which he described as “cutting directly into vivid color” and “drawing with scissors,” involved a new kind of liberty—taking an object out of its tangible space and translating it into a flat sign. The Jazz composition

Forms (1947, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum), for example, contains extremely condensed signs inspired by a Hellenistic female torso (1st or 2nd century AD, Musée Matisse, Nice) from his collection. He explicitly noted that he varied the shapes of the blue and white torsos to give them different weights, as well as to create the impression of different angles.

The space of many of Matisse’s early cut-outs is organized in terms of a grid, as in

Panel with Mask (1947, Designmuseum Danmark), where the background is divided into five rectangular panels. The horizontal panel at the top contains a mask, seen face on, while the two bottom panels contain plant forms. The most radically imaginative signs appear in the two vertical panels just below the mask, which contain highly abstracted representations of animals: a barely recognizable reindeer or caribou on the left, identifiable by its rack of antlers; and an equally abstracted profile of a skull, with its prominent mandible and teeth, on the right.

Matisse made no major paintings after 1948, but continued to draw, showing a marked preference for brush and ink, which could create thick, bold lines.

A 1951 photograph by Philippe Halsmann depicts the artist in his bed, making cut-outs in his bedroom-studio in Nice, with above him a calligraphy panel from China (Qing dynasty, 19th century, Musée Matisse, Nice), a model for Matisse of alternate approaches to representation and sign-making. A series of four simplified drawings of a standing model hangs below the panel, one under each character. Similar gestural marks can be seen in a drawing from

Matisse’s Acrobat series (1952, Centre Pompidou, Paris), where the curving forms of the body are powerfully compressed within the frame. With Chinese calligraphy as an example for his late works on paper, Matisse animated his subjects with a combination of absolute control of ink and seemingly effortless spontaneity.

Additional studio photographs, including one taken by Matisse’s assistant Lydia Delectorskaya in 1952, reveal the calligraphy panel’s role in the development of his cut-outs in progress, especially in the conceptual play with the spatial relations between figure and ground.

While an “allover” effect, in which everything seems to happen at once, usually dominates Matisse’s cut-outs, the exhibition also reveals his experimentation with overlapping and radiating forms. This can be seen in

Mimosa (1949–51, Ikeda Museum of 20th Century Art) and

maquettes for the front and back of a red chasuble (late 1950–52, Museum of Modern Art, New York) designed for the Chapel of the Rosary of the Dominican Nuns of Vence.