The first retrospective of the work of French painter Pierre Bonnard to be shown in New York since 1964 appeared at The Museum of Modern Art June 21-October 13, 1998. One of the most enigmatic of the great artists of the twentieth century, Bonnard (1867-1947) is perhaps best known for his extraordinary colors and sensuous nudes. As this comprehensive exhibition makes clear, however, Bonnard is not simply a painter of hedonistic beauty, but one of the great masters of structure and composition, who reconfigured pictorial space to convey complex emotional states.

By focusing on interiors, still lifes, landscapes, and figure paintings, including the famous bath paintings of his enigmatic wife, Marthe, as well as the remarkable self-portraits, this exhibition emphasized the consistency of Bonnard's preoccupation with the physical as modified by color and light, and showed how he was able to keep reshaping the familiar through compositions of increasing complexity, daring, and originality. Comprising some 80 works, Bonnard concentrates on the artist's foremost period of innovation, beginning in the mid-1910s. It presents celebrated works from public collections and little-known works in private hands, some of which had never been seen in the United States before. The exhibition also brought together the largest number of Bonnard selfportraits to be shown in one place, concluding with the stark and moving images of the artist's last years.

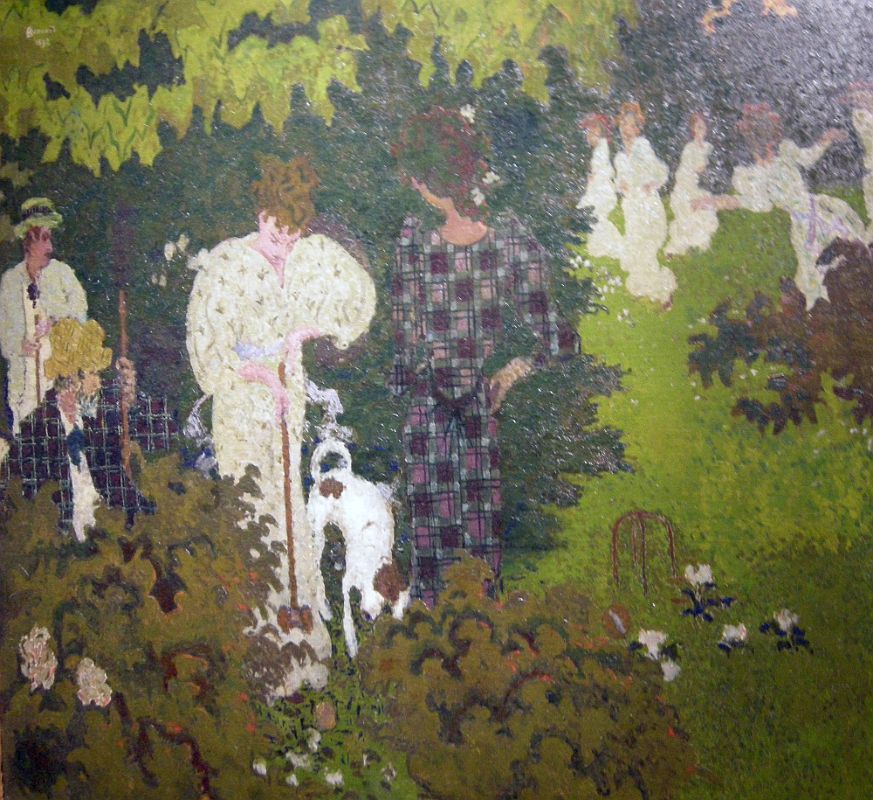

Bonnard occupied eight galleries. The first two showed the unfolding of Bonnard's art from around 1890 until the late 1920s. The remaining six galleries showed his later paintings grouped according to subject matter. Japanese prints and the work of Paul Gauguin influence early works like

Intimacy (1891)

and The Croquet Game (1892),

in which Bonnard's fascination with how patterning can be used to hide things in a painting, slowing one's perception of them, is already evident. By 1900 Bonnard's subject matter had become moments of perception--he wanted to convey what it was like to come upon something unexpectedly for the first time. Bonnard surprised the viewer by making things strange: Everyday objects are oddly shaped, of uncertain texture or incredible color, hard to decipher, hidden in unlikely corners or reflected in mirrors, and so on. Having stopped a moment of time, he asks for our participation in unpacking the complexity of detail to be found there.

By 1920, Bonnard's mature style was formed and, while it did change as the years passed, the stylistic changes are finally less important than how Bonnard treated his key subjects--still life, landscape, bathers, interiors, and self-portraits.

Like all of Bonnard's mature works, his still lifes were painted on lengths of canvas tacked to the wall, some of them large enough to accommodate more than one picture. Bonnard would often crop the painted area slightly to square off the work, but he sometimes left raw canvas around the edges, as in

Basket of Fruit Reflected in a Mirror (1944-46).

In either case, he paid particular attention to the edges of a painting, often reserving his most enigmatic or fragmentary imagery for the margins. This is most evident, perhaps, in the

.+The+Provencal+Jug+1930.jpg)

Provençal Jug of 1930,

which shows the hand and arm of an unseen figure on the right. Bonnard's landscapes form a distinct group within his oeuvre. He made a point of leaving his own garden relatively untended, and his landscape paintings delight in the natural disorder of nature. They are, by far, the densest and most continuously patterned of his works. The range of markings is extraordinary: Dots, lines, bands, patches, scribbles, and streaks of multiple colors configure a strikingly active visual realm, a flat but dynamic map-making that opens into depth beneath the viewer's gaze.

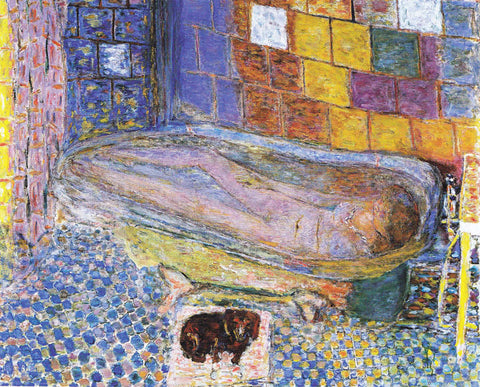

Bonnard's early images of female bathers were unquestionably influenced by the work of Edgar Degas--but eschew Degas's uncomfortably stressful poses for a mixture of frank domestic realism and a note of idealization taken from classical sculpture.

The three late bathtub paintings that were on view--

Nude in the Bath (1936),

The Large Bath, Nude (1937-9),

Nude in the Bath and Small Dog (1941-6)

--are widely considered the culmination of Bonnard's career. Returning to the image of immersed bathing in a 1925 painting, the artist makes what had been, in part, tomblike into something closer to a shrine--suggesting not only mortality but also the commemoration and celebration of things carnal. (In fact, Marthe died in 1942, while Nude in the Bath and Small Dog was in progress.) The figure of Marthe--whose likeness appears in some 380 of Bonnard's works--is at once iconic in a grand, distant way and an all-too-proximate fleshy substance, both peacefully floating and seeming to dissolve. The bathroom tiles form a iridescent screen that glitters and sparkles brilliantly.

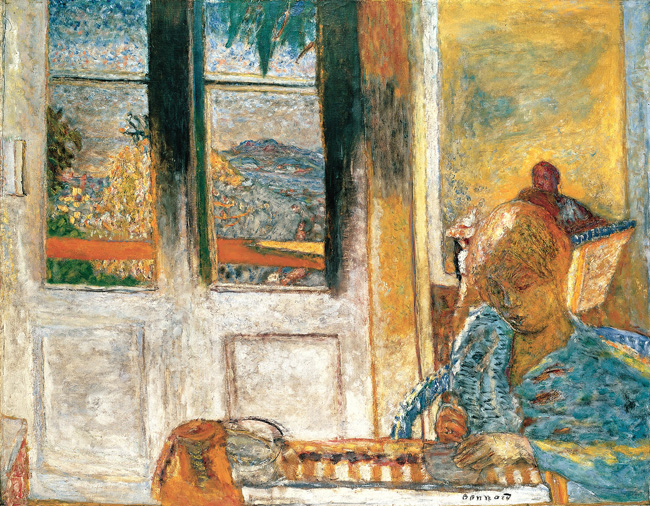

Bonnard's interiors are often presented as luminous spaces filled with familiar objects that become more unfamiliar the longer you examine them. The artist was often drawn to the same interior, as if trying to unravel its mystery. MoMA's magnificent

Dining Room Overlooking the Garden (The Breakfast Room) (1930-1), for example,

and Still Life in Front of the Window (1931)

show the same room at Arcachon, near Bordeaux;

Large Dining Room Overlooking the Garden (1934-5)

and Table in Front of the Window (1934-5)

depict the same room in a rented villa near Deauville;

and The French Window (1932)

and The Breakfast Table (1936)

are from the same room in Bonnard's house at Le Cannet.

The most daring of Bonnard's self-portraits make it clear that they are mirrored representations. In most of these late works the subject is transparently Bonnard's own mortality, and in two works,

Portrait of the Painter in a Red Dressing Gown (1943)

and Self-Portrait (1945),

this is metaphorically expressed by the wartime blackout curtain depicted next to the artist's image. They are among the most poignant self-representations in Western art: querulous apparitions, despairing, frightened, selfeffacing. Bonnard died in January 1947. Some fifteen months later, in May 1948, MoMA opened its first retrospective exhibition of his work; a second was held in 1964. This third Bonnard retrospective at the Museum celebrated a career that ended more than half a century ago but remains as vital and challenging as any in contemporary art.

Bonnard was organized by the Tate Gallery, London, in collaboration with The Museum of Modern Art. It was curated by Sarah Whitfield, independent Art Historian, for the Tate Gallery, in consultation with John Elderfield and art historian and critic David Sylvester. It was coordinated for and installed at The Museum of Modern Art by Mr. Elderfield, who also contributed an essay to the exhibition catalogue, and refined the selection of works for the New York showing.

Bonnard was shown at the Tate Gallery, London (February 12-May 17, 1998) prior to opening at MoMA, its final venue.

PUBLICATION

Bonnard, by Sarah Whitfield and John Elderfield. 270 pages; 273 illustrations (115 in color). Clothbound published in the United States and Canada by Harry N. Abrams, Inc.,