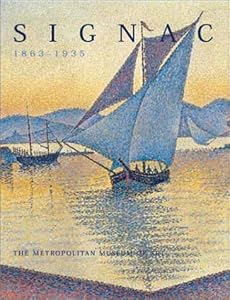

On view at The Metropolitan Museum of Art from October 9 through December 30, 2001, Signac 1863-1935: Master Neo-Impressionist, was the first major retrospective of the artist's work in nearly 40 years. Best known for his luminous Mediterranean seascapes rendered in a myriad of "dots" – and later mosaic-like squares – of color, Signac adapted the "pointillist" technique of Georges Seurat with stunning visual impact. The exhibition featured 121 works, including some 70 oils and a rich selection of Signac's watercolors, drawings, and prints, providing an unprecedented overview of the artist's 50-year career.

Often viewed as "the second man of Neo-Impressionism," Paul Signac (1863-1935) has long been considered an artist of talent in the shadow of the more celebrated Seurat. The exhibition and its accompanying catalogue placed the emphasis squarely on Signac's own personal accomplishments so that the unique character of his oeuvre, his artistic process, and the full range of his activities, relationships, and contributions were illuminated.

The exhibition was organized by The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Réunion des musées nationaux/Musée d'Orsay in Paris, and the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

Long overshadowed by his more celebrated contemporary Georges Seurat, Signac created an extraordinary body of work – most remarkable are his shimmering seascapes and luminous views of the French Riviera. In these works of vivid and pulsating color, Signac fully explored and expanded upon the innovations of Seurat's divisionist painting technique creating images with an intensity and expressive power that belong to him alone

Arranged chronologically, the selection of works traced Signac's development from an art based on observation and direct study of nature, through the rigor and optical precision of Neo-Impressionism to a more subjective art based on his own concepts of pictorial and social harmony. Essentially self-taught, Signac's first works, plein-air studies painted in the early 1880s in Paris and its neighboring suburbs, reveal the lessons he absorbed from Monet, Guillaumin, Caillebotte, and other Impressionists whose examples were his starting point.

By the end of the decade, Seurat's art was the crucial catalyst for the evolution of Signac's painting, providing a model for his technique, his manner of working and even, on occasion, the design of his compositions. Notwithstanding Signac's romantic bent, his more tactile brushstrokes and his stronger color contrasts, it was not until the 1890s – after the death of Seurat – that his work fully came into its own. Signac developed a bolder and looser technique, relying increasingly on the dramatic and architectonic play of color. His discovery of "the joy of watercolor" in 1892 – a medium in which, after Cézanne, he was to become the undisputed master in the 20th century – offered a vehicle for a freer and livelier means of expression, one well-suited to his restless, peripatetic lifestyle. In the best of his late works Signac combined the sensual legacy of his first pictures with the cool rationality of Neo-Impressionism to create images of extraordinary chromatic richness and feeling.

From an excellent review in FRANCE Magazine(some images, link added):

On view are many of the well-known oils he did before 1891. There is the super-modern

"Gas Tanks at Clichy" (1886),

in which an unsentimental view of the past blends with a fearless glimpse at the future; the ultra-decorous

"Dining Room" (1886-87),

a tour-de-force in which Signac characteristically lavishes attention on astonishingly subtle details of light and shadow;

the practically existentialist "Sunday" (1888-1890),

depicting a man and woman with their backs to each other in a stiflingly lovely salon;

and the slightly psychedelic, Japonism-influenced 1890-91

Portrait of Félix Fénéon, the artist’s close friend and first biographer.

These are works of extraordinary skill and thought. Then there are the exhilarating watercolors and propulsive oils done after Signac’s move to Saint-Tropez in 1892, when his personal 20th century seems to have begun. These works steal the show. Here the artist seems to be stretching beyond definition by the other artists and movements he espoused and sailing into his own waters with the heightened self-determination that would characterize so many of the subsequent century’s most radical artists. Look at the electric grandeur of

"The Port at Sunset, Saint-Tropez, Opus 236" (1892)

and the exuberant freedom of

"Still Life With Fruit and Vegetables" (1926),

both of which seem so jazzed that they might be a spin or two away from mid-century abstraction.

An avid yachtsman who settled in Saint-Tropez in 1892, Signac is celebrated for his "The Ports of France," glorious views of port towns along the French coast:

Port-en-Bessin. Le Catel, 1884

and his resplendent seascapes, e.g.

Stiff Northwest Breeze, Saint-Briac 1885.

Prominently featured in the exhibition, these sea and harbor scenes in oil and watercolor were joined by lesser known works, among them his early views of the industrialized suburbs of Paris, the vibrant watercolor still lifes of his maturity, and striking ink drawings he made at the end of his career. Signac's

Women at the Well (1892, Musée d'Orsay, Paris)

completed the survey.

The planning of the exhibition was greatly facilitated by the recently published catalogue raisonné of Signac's work by Françoise Cachin, which combines her insight as the artist's granddaughter and acumen as an art historian. Her assistant on this publication, Marina Ferretti-Bocquillon, author of several articles and books devoted to Signac, contributed to the present catalogue and worked closely with the curators, Anne Distel, Chief Curator of the Musée d'Orsay, John Leighton, Director of the Van Gogh Museum, and Susan Alyson Stein, Associate Curator of European Paintings at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, on the selection of works for the exhibition.

A fully illustrated scholarly catalogue, with individual entries on the works included in the exhibition and six introductory essays, was published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and distributed by Yale University Press. The first three essays focus on Signac's respective efforts as a painter, as a watercolorist and draftsman, and as a printmaker. The final essays discuss Signac's myriad relationships with other artists and his activities as a writer, spokesman for the Neo-Impressionist movement, exhibition organizer, political and social activist, yachtsman, and collector. The main body of the book, which provides in-depth entries and color plates for 182 works, is divided into four sections, each prefaced by an overview of the chronological period – Impressionism: 1883-1885; Neo-Impressionism, 1886-1891; Saint-Tropez, 1892-1906; and Ports and Travels: Signac in the Twentieth Century.

To complement the major exhibition Signac 1863-1935: Master Neo-Impressionist, The Metropolitan Museum of Art presented paintings, drawings, and watercolors – selected entirely from the Museum's own collections – by Charles Angrand, Henri-Edmond Cross, Maximilien Luce, Hippolyte Petitjean and other artists who, like Paul Signac, exuberantly followed the groundbreaking techniques of optical painting introduced in the 1880s by Georges Seurat. On view at the Metropolitan from October 2 through December 30, 2001, Neo-Impressionism: The Circle of Paul Signac featured some 60 works by these artists as well as by the better-known Signac and Seurat.

Flourishing from 1886 to 1906, the artists who worked in this avant-garde style came to be called Neo-Impressionists. The term was coined by art critic Félix Fénéon in his review of the eighth and last Impressionist exhibition (1886) to describe the work of Paul Signac, Georges Seurat, and, remarkably, Camille Pissarro, pioneers of a daring new vision that deviated distinctly from the waning Impressionist school.

Neo-Impressionism extended its reach to Belgium as well, where an avant-garde group known as Les Vingts (Les XX) embraced Seurat's ideals following the 1887 exhibition in Brussels of his masterpiece Sunday Afternoon on the Island of the Grand Jatte. Théo van Rysselberghe was a member of this highly visible Belgian circle, and the exhibition features several examples of his work. Even Henri Matisse briefly experimented with a Neo-Impressionist technique, prompted in part by the publication of Signac's manifesto From Eugène Delacroix to Neo-Impressionism and by the invitation to paint with Signac at his Saint-Tropez residence. Matisse spent nearly a year in Signac's company.

Neo-Impressionists eschewed the random spontaneity of Impressionism. They sought to impose order on the visual experience of nature through codified, scientific principles. An optical theory known as mélange optique was formulated to describe the idea that separate, often contrasting colors would combine in the eye of the viewer to achieve the desired chromatic effect. The separation of color through individual strokes of pigment came to be known as "Divisionism" while the application of precise dots of paint came to be called "Pointillism." According to Neo-Impressionist theory, the application of paint in this fashion set up vibrations of colored light that produced an optical purity not achieved by the conventional mixing of pigments.

The rigid theoretical tenets of optical painting upheld by Neo-Impressionism's standard-bearer, George Seurat, gave way to a more fluid technique following his untimely death in 1891. In the luminous watercolors of Henri-Edmond Cross, for example, small, precise brush marks were replaced by long, mosaic-like strokes and clear, contrasting hues by a vibrant, saturated palette. While some artists like Henri Matisse merely flirted with Neo-Impressionism and others like Camille Pissarro renounced it entirely, Seurat's legacy extended well into the 20th century in the works of Cross and Signac. Poised between Impressionism in the 19th century and Fauvism and Cubism in the 20th, Neo-Impressionism brought with it a new awareness of the formal aspects of paintings and a theoretical language by which to paint.

Neo-Impressionism: The Circle of Paul Signac was organized by Dita Amory, Associate Curator, Robert Lehman Collection. Exhibition design is by Michael Langley, Exhibition Designer, with graphics by Sophia Geronimus, Graphic Designer; and lighting by Zack Zanolli, Lighting Designer.