For a few weeks, the Albertina will afford its visitors a glimpse into

an archive of dreams when the Musée d’Orsay opens its vaults to lend the

graphic gems of its collection for the first time ever to a museum outside of

France from 30 January to 3 May 2015. This major presentation of 19th-century

French art will feature 130 works.

Delicate pastels by Edgar Degas, Georges Seurat and Odilon Redon,

painterly gouaches by Honoré Daumier and Gustave Moreau, fine watercolours by

Paul Cézanne, and works by salon artists who were highly esteemed in their day

will come together to provide a sweeping look at the French art of drawing.

Politically oriented realism will be seen as realised by its most

prominent protagonists: social conflicts dealt with in the era’s courtrooms are

exaggerated and contorted to the point of caricature by Honoré Daumier, while

Gustave Courbet and Ernest Meissonier document barricade battles and

significant political turning points on sheets of sketch paper. Giovanni

Segantini and Jean-François Millet, on the other hand, bathe monumentally

portrayed farmers and fisherfolk in a mystical light and show workers frozen

still in poses that aestheticise their repetitive gestures.

These socially motivated compositions will contrast provocatively with

works by impressionist painters including Paul Cézanne with his sundrenched

landscapes from the south of France, or Eugène Boudin with his airy,

atmospheric market depictions. Both artists allow the bright radiance of their

paper to shine through in places, and they bring a skilful lightness to bear in

constructing their motifs out of nearly geometric surfaces. Light is also a key

element in the works by Edgar Degas: his drawings observe dancers from hidden

vantage points as they work through their private exercises and play out

intimate scenes. And like Aristide Maillol, Degas also devotes himself to the classical

genre of the nude, infusing it with seemingly banal everyday activities to give

rise to something like a modern feminine divinity, a modern Venus.

Alexandre Cabanel and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, on the other hand, show

that despite all modern efforts, the 19th century’s second half

still saw the traditions of the academie

française held high: Cabanel’s The

Birth of Venus represents the zenith of classicism after Ingres or Raphael,

celebrating the classical ideal of beauty as well as the rules and tastes of

the salon. And literary figures inhabit narrative masterpieces by Edward

Burne-Jones, Jean Léon Gérome, and František Kupka, which this presentation

places in dialogue with drawings that were created as book illustrations. These

include Jean-Paul Laurens’s grisailles for Goethe’s Faust, a drawing by the Pre-Raphaelite William Holman Hunt for John

Keats’s Isabella, and finally Maurice

Denis’s illustrations for Les fiorettis

de saint François d’Assise [Little Flowers of St. Francis].

Odilon Redon conjures up mysterious and puzzling depictions by breathing

life into the technique of charcoal drawing: his “noirs” give form to a

suggestive, spiritual world akin to the equally dark but pointillist drawings

by Georges Seurat. These, done in black Conté crayon, are lent definition not

by lines but by the contrast between the subtle nuances of the black drawing

utensils and the whiteness of the paper - resulting in hazy and mysterious

silhouettes. Felicien Rops and Gustave Moreau peer into the abysses of the

human soul: their works show monsters and chimeras, and their reinventions of

Salomé, Medea, and Medusa serve well to illustrate the notions that surrounded

the turn-of-the-century femme fatale.

The way through this seemingly inscrutable labyrinth of styles, themes,

and motifs that simultaneously captivated the 19th-century art world

will be shown by Werner Spies, former director of the Musée National d’Art

Moderne at the Centre Pompidou. Spies compiled the selection of works to be

featured in this exhibition.

And for the catalogue being published to mark the occasion, numerous

artists, authors, filmmakers and architects have provided personal written

contributions and interpretations of individual works as expressions of their

bond of friendship with this esteemed curator.

Curator: Prof. Dr. Werner Spies

Introspection

Closing one’s eyes in order to behold one’s own self in the dark – this form of introspection caused many artists to portray themselves with their eyes in shadows. The mysterious darkness of their eyes expresses doubt, pain, delusion, and a fear of the unknown, of what lies beyond, of the face of the night – the fear of death. The pain-stricken face of Charles Baudelaire, with its sorrowful eyes, stands out against ‘this blackness that produces light’ (Victor Hugo). The author of The Flowers of Evil sees man torn between an ideal world and world-weariness. Courbet presents himself as a disregarded and offended artist who has been insulted by society and defies the world as a free man, ‘un homme libre’, firmly holding on to his canvas. Jean-François Millet’s face betrays the melancholy accompanying artistic crises. Scrutinising his mirror image, Henri Fantin-Latour weighs it against the portray that appears behind his closed eyes, i.e., before the eye of his mind. In Léon Spilliaert’s self-portrait, the eyes lie in deep, dark holes from which the mirror reflects the artist’s hallucinations about his own transience. Pain and a fear of death are also written all over the face of the German artist Lovis Corinth in the works from his late period. The older he grew, the more he was plagued with self-doubt and increasingly perceived a threatening infirmity in his mirror image.

Architectural Visions as the Spawn of Bourgeois Imagination

Delving into a dream in order to soar to the heady heights of unrealisable utopia: around the turn of the century, this was what François Garas was striving for. And because he thought that utility stood in the way of beauty, he refused to actually build things and committed himself entirely to thought experiments. His architecture was only realised on the drawing board and in the form of models. He dedicated his utopian temple complex to the freedom of thoughts and ideas. Unfolding into infinity, they are just as unlimited as the unfinished building itself. At the foot of the temple, Garas envisioned his own house, where he would develop his architecture in seclusion from the world. Other architects were dreaming of the past. Some felt the structure of the Eiffel Tower, a masterpiece of engineering, to be an expression of banality: on the occasion of the 1900 Paris Universal Exhibition, its construction elements were to be hidden. Henri Toussaint contrived a palace of electricity for which the base of the iron lattice tower should be generously concealed. The entire 19th century oscillated between the antipodes of a future-oriented belief in technology and a poetically distorted reality oriented towards the past – between the poles of utopia, realism, and a sense of longing for a lost idyll. The exhibition Archives of the Dream traces the 19th century’s fault lines between romanticisation and reality, between the Salon and the avant-garde.

Labour and Time Standing Still

Jean-François Millet

Harvesters Resting or Ruth and Boasz, sketch for the painting of the same title, 1850–1853

© Musée d´Orsay, Paris, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais, Hervé Lewandowski

In the art of

Jean-François Millet and Giovanni Segantini, farm labourers and peasants

returning from work at the fall of darkness bend under their heavy loads.

Leaning out of their boats, fishermen throw their traps by moonlight. During

the day, they relax in the sun and abandon themselves to daydreams. In such

moments, time stands still. At dusk, however, when day and night blend

together, movement stirs anew, and the farmer’s wife heads for home with her

herd.

Millet and Segantini

mark the beginning and the end of realism. Their drawings are separated by half

a century, but they share the atmospheric and tranquil interpretation of

peasants and farmworkers giving in to the cycle of life. These images are

devoid of an acute presence, of accusation and pathos. They do not romanticise

life in the countryside, in spite of their conciliatory, diffuse light. Neither

do they deplore the social misery of the industrial age. These pictures also

resemble each other in terms of the rhythmical repetition of movement: most

simple gestures become symbols of human existence per se.

Honoré Daumier

Honoré Daumier

The Print Collectors, 1863–1865

Chalk, pen and black ink, watercolour

© Musée d´Orsay, Paris, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais, Tony Querrec

No one pilloried the

faces of the bourgeoisie and its double moral standards more fittingly than

Honoré Daumier. He exposed these self-righteous and haughty citizens to

dazzling light and to the caricaturist’s scorn. Daumier’s victims were

ivory-tower amateurs and collectors who preferred to stick with their own kind

and mirror-gazing lawyers who thrust themselves into the limelight with the

mendacity of hollow pathos.

Daumier did not

spare the privileged social strata. His caricatures extracted the truth from

behind the scenes of the Second Empire and unveiled the complacency of its

hypocritical upper middle classes. Parliamentarians, judges, barristers, and

artists were the profiteers of the authoritarian regime of Napoleon III and a

parliament that had deprived itself of control and had placed substantial power

in the hands of corrupt courts.

Honoré Daumier

The Carnival Parade, ca. 1865

Chalk, pen and black ink, watercolour and gouache

© Musee d´Orsay, Paris, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais, Franck Raux

Yet Daumier also

parodied the outsiders of society, figures related to the circus. The showman’s

outcry goes unheard; the spectators remain indifferent, no matter how

threatening the monster in the background may appear.

Daumier was the

first prominent artist to resort to caricature as a medium of expression in

realism, for only the exaggeration of reality allowed him to render its

ugliness uncensored.

Ernest Meissonier

In June 1848, the

working class unsuccessfully rose to protest against the abolition of the

National Workshops, which had been introduced as a measure against

unemployment. The young Second Republic, which had emerged from the demolished

barricades in February 1848, brutally smashed the dream of equality and

fraternity. An artillery captain in the National Guard, Ernest Meissonier

participated in the fights and captured the events on the spot immediately

after the barricades in the rue de la Mortellerie in Paris had been stormed. He

produced a small, inconspicuous masterpiece, which due to its relentless

observation of the revolutionaries’ mutilated bodies has been chosen as the

historical prelude to The Archives of the

Dream: an image that would gave birth to both the idylls fleeing the

cruelty of reality and the resulting nightmares.

Historicism and the

Salon

Year after year,

large crowds stormed the huge exhibitions of the Paris Salon in order to admire

the latest paintings or pour scorn and derision on them to the critics’

applause. Past reviews of the Salon, whether expressing admiration or contempt,

and today’s assessment of the works in question frequently diverge

considerably. In the 19th century, Alexandre Cabanel was a celebrated artist,

while Édouard Manet was misunderstood as a provocative agitator. Because of its

feminine beauty, Cabanel’s Birth of Venus

aroused enthusiasm, whereas Manet’s Odalisque

was vehemently rejected because of its ugliness. Manet’s Reclining Nude with a Cat likely depicts a prostitute, who looks at

the spectator provocatively: an affront to academic tradition. Yet the poet and

‘social reporter’ Émile Zola was well aware that Manet’s Odalisque would pave the way for modernism. Such masters of

idealising history painting as Lawrence Alma-Tadema or Jean-Paul Laurens soon

fell into oblivion during the long years of the modernist era. Only recently

have their works no longer been misunderstood as painted literature, but have

been reassessed as autonomous and virtuoso products of visual narration.

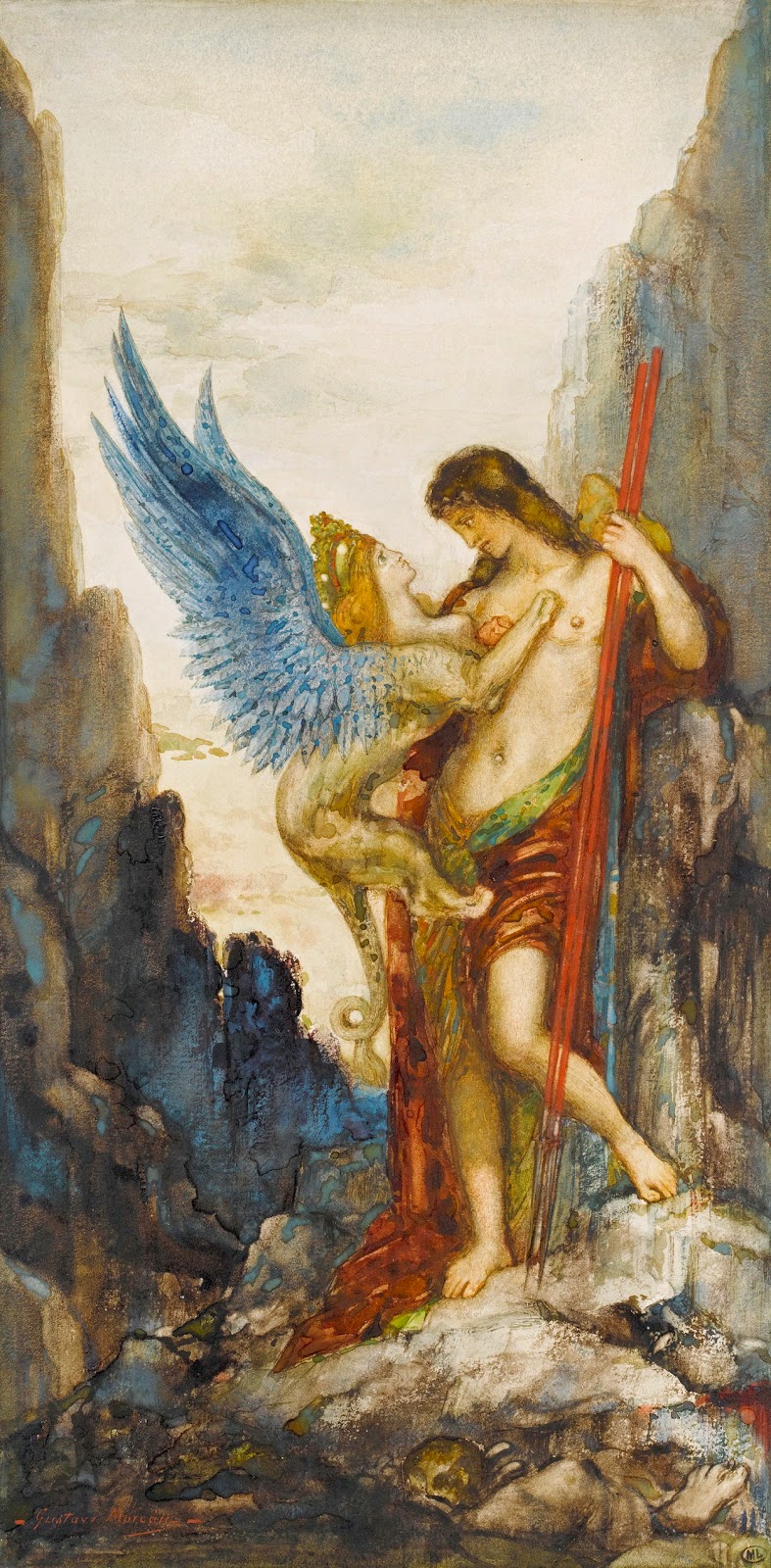

Gustave Moreau

Gustave Moreau was a

‘collector of dreams’. Images came naturally to the mind of this shy, learned

maverick, fired by myths and literary inspiration. Moreau preferred the

jewel-like transparency of watercolour painting. He owed his imagination and

inventiveness to his enormous visual memory and erudition. His works stand out

against the dark visions of other Symbolists like glittering diamonds.

Like other escapists, Gustave Moreau was an anti-naturalist and vehement

opponent of the depiction of modern life. He was fascinated by the poetry of

the Old Masters in the Louvre. Far from being a history painter committed to

archaeological accuracy, he presented his visions of dreams as an alternative

to realism, surprising beholders with his reinterpretations of traditional

subject matter. Long before Hofmannsthal and Richard Strauss, he had Salome

engage in an erotic dialogue with the head of John the Baptist.

In his Oedipus and the Sphinx, Moreau

memorialised ‘the mystery of the woman’ before Freud appeared on the scene.

Moreau’s preference for decorative detail and its sensual splendour and

sumptuous surfaces derive from his knowledge of oriental weapons, garments,

rugs, and jewellery.

Gustave Moreau

Oedipus and the Sphinx, 1882

© Musée d´Orsay, Paris, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais, Thierry Le Mage

Carlos Schwabe

Carlos Schwabe

Death and the Grave Digger, 1895 (watercoloured in 1900)

© Musée d´Orsay, Paris, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais, Jean-Gilles Berizzi

In his pictures, Carlos Schwabe hallucinates death as

the fictitious body of the ‘femme fatale’ – a woman embodying the male fear of

a death brought about by lust. The angel is a deathly female creature that

holds the promise of final bliss – not in the guise of satanic depravity like in

the case of Félicien Rops, but in the shape of a beautiful woman. The female

angel of death, furnished with scythe-shaped wings, appears as a redeemer

exonerating the gravedigger from his dreary existence. The angel’s smouldering

colours recall those of the scarab, the Egyptian symbol of the sun god and of

rebirth.

In Schwabe’s art, winged female figures are guardian angels – be it that

they protect man from adversity in the manner of archangels or that they

relieve man from the burden of life through death. In his book illustrations

for Le Rêve [The Dream] by Émile Zola, the writer’s least naturalistic novel,

Schwabe, a Symbolist, saw plenty of room for his subjective interpretation of

the story and illustrated scenes that cannot even be found in the novel. Zola,

a Naturalist, complained about the lack of realism of the Symbolist images,

which took the beholder to a phantasmagorical world. Convinced of the artistic

merit of his illustrations, Schwabe exhibited them successfully at the Salon de

la Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts before the book was published.

Félicien Rops

Rops shocked the public and

attacked the Catholic Church. His pornographically drastic illustrations

unsettled the prudish sexual morality of the 19th century. In his bizarre and

highly inventive works, the artist mockingly and impiously roused the demons of

repressed desires, which eventually closed in on society and its tabooed

sexuality. Rops reinstated the mysterious force of voluptuousness and restored

it to the devilish context to which it had been assigned by religion. According

to the Symbolist poet Joris-Karl Huysmans, Rops’s designs can be referred to as

‘Catholic works’ for this very reason.

In 1874, Rops settled in Paris, where he gave free rein to his talents

and ideas as a graphic artist. He drew a series of illustrations for Barbey

d’Aurevilly’s Les Diaboliques. On the

frontispiece, a nude female figure nestles up against the cold stone of a

sphinx and requests to be let in ‘on the supernatural secret of new sins and a

voluptuousness undreamt of’ (Joris-Karl Huysmans). Satan, an elderly gentleman in

a dark suit and with a monocle, is seated between the sphinx’s wings and

listens lecherously. He is the symbol of an aged and exhausted society that has

suppressed its sexual desires.

The Pre-Raphaelites

and the Aestheticism of the 19th Century

The dream of art’s renewal celebrated the past.

William Holman Hunt vehemently rejected academism and its teachings, which

relied on the ‘classical’ art of Raphael. In 1848, Hunt founded the

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in London together with other artists. They pleaded

for a return to an aestheticism void of pathos as it had prevailed during the

period before Raphael and the Roman High Renaissance. Their drawings,

characterised by precise contours and a lack of modelling, resembled those of

medieval craftsmen. Outline drawings based on Italian frescoes of the Early

Renaissance served as their guide. Nature was their unrelenting teacher and

supreme model.

Medieval devotional

literature became a moral authority for the Pre-Raphaelites and their themes.

They illustrated works by Dante and Petrarch, virtuous poetry of the early

modern age, and Boccaccio’s Decameron.

In deliberate opposition to early industrial mass production, Walter Crane

sought to reassert the status of craftsmanship. In his book illustrations, he gave

equal attention and care to the figural elements and to the floral ornaments in

the decorative borders.

Edward Burne-Jones

aesthetically transfigured the games and intrigues between the sexes. His drawn

head of the goddess of Fortune belongs to a ‘femme fragile’: the idealised yet

no less fictitious counterpart of the menacing vamp, the man-devouring ‘femme

fatale’. Delicately built, anaemic, and frail, she requires male

protection.

Rodolphe Bresdin

Bresdin was an ‘artiste maudit’ – a misjudged artist

who was excluded from the official art scene and would ultimately deliberately

choose the way into self-destructive isolation. Bresdin’s work relies on Dutch

17th-century art, on Rembrandt and Hercules Seghers. Bresdin’s style as a

draughtsman is obsessive. He meticulously drew his landscapes with a great

sense of precision, losing himself in detail, until a multitude of elements

would overgrow a picture. Dense foliage and lush forests spring not from direct

observation, but from uncontrolled fantasy. In these scenes, man is small and

meaningless. Odilon Redon was Bresdin’s student, friend, and future apologist.

Eugène Boudin and the Landscapes of Gustave Doré and

Edgar Degas

Boudin’s watercolour

brush seems to have swept across the surface spontaneously yet confidently,

causing the transparent, scintillating patches and light-suffused silhouettes

of a lively, colourful market in Brittany to blend in with the paper. He

accurately sketched down the details and later carefully finished his sheets of

studies.

Eugène Boudin was

one of the first painters to consider a fleeting moment – an ‘impression’ –

worth depicting. What Boudin considered unpretentious souvenirs he had painted

in front of the motif for summer visitors paved the way for the future

generation of Impressionists, above all for Monet’s painting ‘en plein air’.

Although Edgar Degas

was primarily a figure painter, he also devoted himself to the landscape, this

quintessential Impressionist genre. Here, too, he preferred the pastel with its

creamy consistency and intensity so as to achieve soft transitions and

brilliant colours.

Degas’s contemporary

Gustave Doré, a prolific illustrator, was also one of the leading landscapists

in 19th-century France. In his landscape watercolours, which the enthusiastic

mountaineer had painted in the Scottish Highlands in 1873, he dispensed with

figures entirely. Drama and narration derive solely from the eloquent twilight,

the gloomy sky, and the solitary, mysteriously glittering lake. Doré’s

landscapes are dream-like, poetic visions inspired by contemporary literature.

In their sublimeness, they hark back to works by William Turner and Gustave

Courbet.

Women at

Their Toilette

Edgar Degas

After the Bath (Woman Drying Her Neck), 1885/86

© Musee d´Orsay, Paris, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais, Herve Lewandowski

In the shadow and out of the limelight of the public stages on which

actresses, dancers, and singers radiated with beauty and charisma, women

pursued their trade in gloomy bars and dimly lit brothels. It was in the

boudoirs of these establishments that Edgar Degas found the models for his

pastels. When he went public with his works, the audience was appalled. The

true-to-life depictions of these unadorned women and their profane corporeality

contradicted the academic beauty ideal mainly because of their realistic postures.

People preferred classical renderings of women in mythological guises and

elegant poses, clearly composed with the possibility of public exhibition at

the official Salons in mind.

Degas, on the other hand, presents women uncompromisingly captured in

intimate activities and realistic contortions while washing, combing, or drying

themselves. The washbowls and zinc tubs indicate the women’s routine of taking

a bath before or after a client’s visit. Degas chose equally unconventional

views, daring perspectives from above, and abruptly cropped motifs in order to

emphasise both the women’s unselfconsciousness while engaging in their habitual

actions and the intimate closeness of the spectator, who remains unnoticed by

them.

Degas – Pastels and Monotypes

Degas saw

himself not only as a decided draughtsman, but also as a declared colourist:

irreconcilable opposites Degas managed to balance in his pastels. The

brilliantly bright and colourful appearance of the pastel ideally suited the

Impressionists in their ‘painting with light’.

The

pastel technique, which was highly appreciated by Venetian and French painters

because of the matt and velvety surface it produced, had reached its peak in

the 18th century. For a pastel, pigments are applied in powdery layers and can

then be loosely blended with a brush, which results in soft transitions and

shimmering surfaces. Having disappeared almost entirely during the period of

Neo-Classicism, the technique was revived and taken to a new zenith by Edgar

Degas. With his parallel and cross-hatching, Degas succeeded in lending his

pastels intensive surface textures without blending the colours. It is amazing

that Degas, the master of light and breezy pastel painting, simultaneously

paved the way for black monotype, which he used to render the dreary atmosphere

in the dark backrooms of brothels.

Degas and the Ballet

Edgar Degas

Spanish Dancer and Leg Studies, study for the pastel Dancer with a Tambourine, ca. 1882

Chalk and pastel

© Musee d´Orsay, Paris, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais, Adrien Didierjean

In countless

drawings, studies, and pastels, Degas devoted himself to the subject of dance –

the ballet: above all, to the young danseuses’ rehearsals and warm-up and

stretching exercises. Unlike such Impressionist landscapists as Monet or

Renoir, who sought to arrest a fleeting light atmosphere, Degas aspired to

capture previously unnoticed movements by constantly varying his unpretentious

motifs: ‘One must draw the same motif over and over again, ten times, a hundred

times, in order to approximate reality as closely as possible.’

In the pastel, light

effects and optical stimuli generated by the colours contribute to a great

degree of realism. The dance that has been frozen in the picture is brought

back to life so as to vividly convey its dynamism.

In his pastels,

Degas rarely depicted the public stage and more frequently rendered the world

hidden behind it. As an ‘abonné’, a regular visitor to the Paris Opera, he had

free access to the dance studio, where, from 1870 onwards, he observed not so

much the stars and protagonists, but rather the pupils, the ‘petits rats’. He

drew them during their hard training, their exercises at the barre, and their

breaks or when they adjusted their costumes. In these private moments Degas

caught them in intimate poses, which his contemporaries frequently felt to be

unaesthetic and too ‘ordinary’.

Paul Cézanne

Paul Cézanne

Montagne Sainte-Victoire, 1900–1902

Graphite and watercolour

© Musée d´Orsay, Paris, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais, Tony Querrec

Southern light softly caresses the Montagne

Sainte-Victoire, whose misty shape rises out of the surrounding land. The blue

haze blends in with the white surface of the paper and directs our gaze into

the depth. The atmosphere and the wide expanse of the landscape, with its

trees, hills, and slopes, flicker and vibrate in pale yellow and green light

reflections. Time stands still; neither time of day nor season diverts us from

this dazzling play of colours and light.

Paul Cézanne drew

and painted by carefully rebuilding nature’s structure on the paper with the

brush: like an architect. He has rendered the Château Noir, a castle in

Provence, with a thin, pointed brush, whereas the rest of the scenery has been

captured much more fluidly and generously. The transparent and modulated

patches of colour leave large parts of the painting ground uncovered. In spite

of all their lightness and brilliance, Cézanne’s watercolours are governed by a

strict geometric structure. Cézanne responded to the fleetingness and

momentariness preferred by his Impressionist friends with an entirely new

pictorial stability that would set the trend for modernism.

What appears to be a

randomly composed still life or a green jug lost in its surroundings seems to

have always existed, since all the elements are firmly rooted in the paper and

the picture’s structure.

Georges Seurat and Neo-Impressionism

With his works, Georges Seurat succeeded in pinpointing the dream of eternity, reliability, stability, and universality in the visual arts. He drew and painted against Impressionism’s philosophy of coincidence, momentariness, spontaneity, and improvisation, meticulously putting his motifs together from a multitude of tiny dots.

Georges Seurat

The Veil, ca. 1883

Conté crayon

© Musée d´Orsay, Paris, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais, Thierry Le Mage

Before Seurat applied his new principles to painting, he exhibited a

number of drawings he referred to as ‘noirs’, just like Odilon Redon. Seurat

used greasy chalks in various degrees of hardness, which allowed him to achieve

subtle transitions. The silhouettes he created on the paper as if by magic are

composed of delicate, yet extremely powerful contrasts of light and shade,

which Seurat employed to examine the effects of chiaroscuro.

Seurat’s cropping of the motif, by which he took the figures to the

picture’s margins, was entirely new and unusual. He thus arrested his

geometrically shaped figures within the sheet’s rectangle. Together with the

artist’s complete renouncement of realistic detail, this results in the great

inner monumentality of his drawings.

Paul Signac was Seurat’s closest companion. As Seurat, the inventor of

Pointillism and victor over Impressionism, died prematurely, Signac would

eventually publicise his theories. The Belgian painter Théo van Rysselberghe

also belonged to the Parisian circle of the Pointillists. He acted as a link to

the artists of this avant-garde movement in Brussels.

Odilon Redon

The world of Odilon

Redon presents itself to us as a disturbing nightmare, gloomy, mysterious, and

enigmatic. Deadly smiling women in the form of spiders, devils wearing masks,

underwater monsters, and Caliban, the animalistic slave in Shakespeare’s Tempest, take the beholder to an

anxiety-ridden world of the unconscious that has been repressed by a

purpose-oriented sense of reality. The charcoal, which is ‘devoid of any

beauty’ (Redon) and which the artist employs to commit his dark, fantastic

world to paper, makes the Symbolist an early explorer of the subconscious mind.

He referred to his drawings as ‘noirs’ – black images – and thus named them

after the ‘colour’ that is used to render the dark aspects of human abysses,

similar to Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll and Mr

Hyde. Redon’s bizarre and grotesque phantasmagorias were inspired by

Hieronymus Bosch, ‘Hell Brueghel’, and Goya and made him the forerunner of the

Surrealists and their depictions of horror.

Symbolism

Society had

forgotten how to dream. Scientific knowledge, Darwinism, and awakening

Freudianism called man’s self-concept into question. But what remains when an

individual’s existence and mind are scrutinised down to the very last nook and

cranny and even religion fails to supply answers to the final doubts? Symbolism

attempted to offer remedies. Its spokesman, Joseph Péladan, proclaimed: ‘The

Louvre will act as a substitute for Notre Dame’ and ‘The artist will rise to

the position of priest, king, and magician.’ Art and literature were considered

capable of expressing the unfathomable mystery, the invisible and unnameable

aspects of the world.

The Symbolists were

not a homogeneous group, yet they shared an interest in new themes, which they

discovered not only in Christian, but also in exotic theologies, as well as in

mysticism, esotericism, spiritualism, and occultism.

Léon Spilliaert

obtained his inspiration from the port town of Ostend. Darkness, emptiness, dim

lights in the city’s fine haze, and a bridge rendered in hardly discernible

colours convey desolation and loneliness.

William Degouve de

Nuncques frequently painted park landscapes in the dark that exhibit confusing

visual axes and lights. For his palette, the artist harked back to James

McNeill Whistler and the latter’s penchant for a combination of painting and

music. The Hungarian painter Jószef Rippl-Rónai, on the other hand, sought to

imitate the appearance of negatives in photography: the light-coloured trees

against the dark background lend his park the ghostly atmosphere of a dubious

place.

Fin de siècle:

Between Belle Époque and Classical Revival

Around the turn of the century, Salome and Medea were

projection figures of a profoundly unsettled society in whose microcosm raged a

war between the sexes: from Oscar Wilde to Otto Weininger and Richard Strauss –

the ‘femme fatale’ lured men to their ruin. In Mariano Fortuny’s art, she even

catapults the man out of the picture.

Fortuny was a painter and fashion designer who invented new treatments

of textile fabrics, including a technique for pleating silk. Salome

triumphantly lifts the plate with the Baptist’s head to the upper margin of the

picture, thus sparing the beholder the ghastly sight. Salome turns her back on

us, presenting her sumptuous, elaborately draped robe. Splendour and beauty

mitigate the horrible event.

In the work of Alfons Mucha, the applied arts were similarly seized by

antique tragedy. On a poster design, the artist stylised the legendary actress

Sarah Bernhardt in the guise of the vengeful heroine Medea and the children

killed by her to the limits of legibility. Iconography came to be governed by

ornament.

As art threatened to be decoratively trivialised, artists sought refuge

in the revival of classical art. Aristide Maillol started out as a designer of

tapestries; after 1900, he turned his attention to sculpture, lending his

monumental figures a statuary stability. After a sojourn in Greece, he was

preoccupied with the idea of ‘pure sculpture’, which he later projected onto

drawings for the sake of a more direct sensual experience. He made use of the

entire surface of the sheet in order to translate the wonderful linear

arabesques into what feels like sculptural monumentality.

Maurice Denis

In 1893, Maurice Denis embarked on a long, fictional

journey into the realm of sensations, desires, and secrets in the company of

his friend, the Symbolist writer André Gide. Denis illustrated Gide’s Le Voyage d’Urien, describing the inner

voyage of an intellectual idler with extremely reduced means. ‘This journey is

but a dream of mine,’ wrote Gide, hiding his vision in the first name of his

fictitious hero ‘[U]rien’. Resorting to a simplicity bordering on abstraction, Denis

translated the story into a new, radically flat visual language of arabesques

and curved lines. The figures, water surfaces, groves, gardens, and ships exist

side by side, without any hierarchy.

After 1900, Denis

sought to revive religious art, illustrating, among other books, the ‘Fioretti

[Little Flowers] of Saint Francis of Assisi’, which contributed to the legends

around the saint through a romanticised account of his life.

Catalogue

The catalogue accompanying the

exhibition – a homage by artists to Werner Spies – offers a unique approach to

the works on view in the form of one hundred statements by the most celebrated

and influential contemporary visual artists, poets, filmmakers, musicians, and

directors:

Adel

Abdessemed Adonis

Nicolas Aiello Jean-Michel

Alberola Anita Albus

Pierre

Alechinsky Eduardo Arroyo Paul

Auster Georg Baselitz Valérie Belin

Christian

Boltanski Luc Bondy Laura

Bossi Fernando

Botero Alfred Brendel

Daniel

Buren Michel Butor Sophie Calle Jean

Clair Tony Cragg

Thomas

Demand Maryline Desbiolles Marc Desgrandchamps Marlene

Dumas

Hans Magnus Enzensberger Philippe

Forest Jean Frémon Gloria Friedmann

Jochen

Gerner Laurent Grasso Mark Grotjahn Durs

Grünbein Andreas Gursky

Yannick

Haenel Peter Handke Michael

Haneke David Hockney Rebecca Horn

Siri Hustvedt Anish

Kapoor Alex Katz William

Kentridge Anselm

Kiefer

Konrad

Klapheck Alexander Kluge Karin Kneffel Imi

Knoebel Jeff Koons

Julia

Kristeva Michael Krüger Jean

Le Gac Peter

Lindbergh Robert Longo

Rosa Loy David

Lynch Jonathan Meese Richard

Meier Annette

Messager

Jean-Michel

Meurice Fran ois Morellet Herta Müller Paul Nizon Pierre Nora

ois Morellet Herta Müller Paul Nizon Pierre Nora

Richard Peduzzi Elizabeth Peyton Jaume Plensa

Christian de Portzamparc Arnulf Rainer Neo Rauch

Yasmina Reza Daniel Richter

Gerhard Richter François Rouan Thomas Ruff Boualem Sansal Sean Scully

Jean-Jacques Sempé Cindy Sherman Kiki Smith Philippe Sollers Botho Strauß

Hiroshi Sugimoto Sam Szafran Gérard Titus-Carmel Jean-Philippe Toussaint

Tomi Ungerer Mario Vargas Llosa Jacques Villeglé Nike Wagner Martin Walser

Wim Wenders Erwin Wurm Yan Pei-Ming