Christie’s Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale on 27 June, 2017

A visionary approach is also seen in the allegory of Max Beckmann’s political masterpiece Birds’ Hell (Hölle der Vögel) (1937-1938, estimate on request), a searing indictment of the Nazi Party and a personal outpouring of anguish akin to

Picasso’s Guernica (1937).

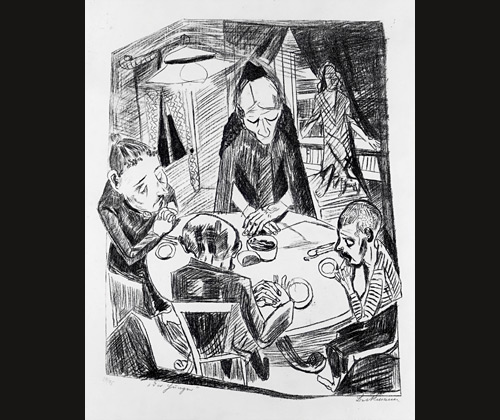

Birds’ Hell (Hölle der Vögel) is ‘an allegory of Nazi Germany. It is a direct attack on the cruelty and conformity that the National Socialist seizure of power brought to Beckmann’s homeland. Its place in Beckmann’s oeuvre corresponds to that occupied by Guernica in Picasso’s artistic development. It is an outcry as loud and as strident as an artistic Weltanschauung would permit. Not since his graphic attacks in

Hunger

and City Night

in the early twenties had Beckmann resorted to such directness, such undisguised social criticism. Birds’ Hell is Beckmann’s J’accuse’ (S. Lackner, Max Beckmann, New York, 1977, p. 130).

Sotheby's 2016

Max Beckmann Schlafende am Strand (Quappi at the Beach) (1927& 1950) Estimate: £800,000-1,200,000

Schlafende am Strand was inspired by Beckmann’s visit to Rimini on the Adriatic coast of Italy, where he spent the summer of 1927 with his wife Quappi. Both

the initial sketch

and the painting remained first in the artist’s and then in Quappi’s possession until the end of her life, the drawing now forming part of the collection of Museum der Bildenden Künste in Leipzig. Quappi, who often featured as a model in Beckmann’s works, is depicted as an image of beauty and youth.The sense of simplicity and joie de vivre is palpable as the artist centres his attention on depicting the simple pleasure of lying on a sunny beach.

SOTHEBY’S TO SELL ONE OF THE GREATEST GERMAN PAINTINGS LEFT IN PRIVATE HANDS MAX BECKMANN’S SELF-PORTRAIT WITH HORN TO BE OFFERED FROM THE COLLECTION OF HIS LIFE-LONG PATRON ON THE EVENING OF MAY 10TH 2001

A visionary approach is also seen in the allegory of Max Beckmann’s political masterpiece Birds’ Hell (Hölle der Vögel) (1937-1938, estimate on request), a searing indictment of the Nazi Party and a personal outpouring of anguish akin to

Picasso’s Guernica (1937).

Birds’ Hell (Hölle der Vögel) is ‘an allegory of Nazi Germany. It is a direct attack on the cruelty and conformity that the National Socialist seizure of power brought to Beckmann’s homeland. Its place in Beckmann’s oeuvre corresponds to that occupied by Guernica in Picasso’s artistic development. It is an outcry as loud and as strident as an artistic Weltanschauung would permit. Not since his graphic attacks in

Hunger

and City Night

in the early twenties had Beckmann resorted to such directness, such undisguised social criticism. Birds’ Hell is Beckmann’s J’accuse’ (S. Lackner, Max Beckmann, New York, 1977, p. 130).

Max Beckmann’s Bird’s Hell (1938, estimate on request) will lead 20th Century at Christie’s, a series of sales that take place from 17 to 30 June 2017, in the Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale on

27 June 2017, when it will be offered at auction for the first time.

One of the most powerful paintings that Beckmann created while in exile

in Amsterdam it presents a searing and unforgettable vision of hell and

is poised to set a world record price for the artist at auction. Begun

in Amsterdam and completed in Paris at the end of 1938, this work ranks

amongst the clearest and most important anti-Nazi statements that the

artist ever made, mirroring the escalating violence, oppression and

terror of the National Socialist regime.

Painted with vigorous, almost gestural brushstrokes and bold, garish colours, Bird’s Hell envelops

the viewer in a sinister underworld in which monstrous bird-like

creatures are engaged in an evil ritual of torture. Presiding over the

scene is a multi-breasted bird who emerges from a pink egg in the centre

of the composition. To her right, a crouching black and yellow bird

looms over golden coins spread before him, while behind the central

figure, a group of naked women stand huddled together. Heightening the

sense of hysteria is the group of figures standing within a glowing,

blood red doorway to the left of the composition. Guarded by another

knife-wielding bird, they return the bird-woman’s gesture, their right

arms raised in unison in the same furious salute. At the front of the

scene, a naked man – the symbol of innocence within this reign of terror

– is shackled to a table, held down by another bird that is slashing

his back in careful, horizontal lines.

Continuing

the Germanic tradition of the depiction of hell, this painting echoes

the gruesome allegorical scenes of Hieronymus Bosch’s famed The Garden of Earthly Delights,

while at the same time, takes aspects of Classicism and mythology to

turn reality into a timeless evocation of human suffering. In this way, Bird’s Hell, like Pablo Picasso’s Guernica or

Max Ernst’s Fireside Angel of the same period, transcends the time and the political situation in which it was made to become a universal and singular symbol of humanity.

Max Ernst’s Fireside Angel of the same period, transcends the time and the political situation in which it was made to become a universal and singular symbol of humanity.

Sotheby's 2016

Max Beckmann Schlafende am Strand (Quappi at the Beach) (1927& 1950) Estimate: £800,000-1,200,000

Schlafende am Strand was inspired by Beckmann’s visit to Rimini on the Adriatic coast of Italy, where he spent the summer of 1927 with his wife Quappi. Both

the initial sketch

and the painting remained first in the artist’s and then in Quappi’s possession until the end of her life, the drawing now forming part of the collection of Museum der Bildenden Künste in Leipzig. Quappi, who often featured as a model in Beckmann’s works, is depicted as an image of beauty and youth.The sense of simplicity and joie de vivre is palpable as the artist centres his attention on depicting the simple pleasure of lying on a sunny beach.

SOTHEBY’S TO SELL ONE OF THE GREATEST GERMAN PAINTINGS LEFT IN PRIVATE HANDS MAX BECKMANN’S SELF-PORTRAIT WITH HORN TO BE OFFERED FROM THE COLLECTION OF HIS LIFE-LONG PATRON ON THE EVENING OF MAY 10TH 2001

On the evening of May 10, 2001 Sotheby’s

in New York will offer for sale one of the greatest German paintings left in

private hands, Max Beckmann’s Self-Portrait with Horn. Painted in Amsterdam in

1938, when Beckmann was in exile following the appearance of his name on the

Nazi list of “degenerate”artists, the painting is being sold from the estate of

his life-long patron, the late Dr. Stephan Lackner. The work, which is

estimated to sell for $7/10 million, will be included in Sotheby’s sale of

Impressionist and Modern Art Part I. The portrait will be on view in Los

Angeles, San Francisco, London, Paris, Zurich, Munich and Cologne prior to its

exhibition and sale in New York.

Stephane Connery, Senior Vice President in

Sotheby’s Impressionist and Modern Art department, said, “Self-Portrait with

Horn is an icon of 20th century art, and certainly the most important German

painting to come up for auction in living memory. This resonant and powerful

work is one of the artist’s most important and magnificent self-portraits, a

compelling statement of 20th century artistic independence under oppression.

The visceral power of this masterpiece is further enhanced by its matte surface

and lively impasto, and by the fact that it is in extremely desirable

condition, having remained both unvarnished and unlined.”

The work, which has

been exhibited widely from late 1930s to the late 1990s,

also appears on the cover of the artist’s catalogue raisonné.

Max Beckmann was

the most important German Modernist artist working between the wars. He was

approaching the peak of his career –with a major retrospective and permanent

museum exhibitions of his work --when the National Socialist party came to

power in Germany in 1933. In 1937 ten of Beckmann’s paintings were included in

the notorious “Entartete Kunst”(“Degenerate art”) exhibition in the Munich

Arkaden, and the artist fled with his wife to Amsterdam. It was at this point

that Beckmann undertook Self-Portrait with Horn.

In Self-Portrait with Horn,

Beckmann depicts himself alone in a confined, narrow space holding a Waldhorn

(German hunting horn) in his left hand and wearing a black-and red-striped

housecoat.

Stephane Connery has written that “in the composition the artist has

created a penetrating self-image that lies on threshold between darkness and

light, pessimism and hope, self-doubt and self-knowledge.”The psychological

effect of the work is compounded by the inclusion of the hunting horn, which in

German literature and painting was used as a symbol of Romanticism. Beckmann’s

nostalgia for his homeland during his exile is apparent by his use of this

attribute. Remarkably, a photograph preserves for us an earlier stage of this

work in which the artist is smiling, apparently enchanted by the horn’s melody.

The final version reflects a profound shift in attitude and mood, with the

artist’s smile having been replaced by a melange of doubt, bitterness,

disappointment, and uncertainty.

Stephane Connery continued, “Self-Portrait with Horn can

also be read as a silent victory call after a very particular ‘hunt’. Through

his craft and artistry, Beckmann has escaped the clampdown of the National

Socialist regime and the increasing constraint resulting from the public

disgrace under which many of his fellow artists were living and working in

Germany.”

Stephen Lackner was born in Paris in 1910 and spent most of his

childhood in Germany. In the 1930’s he began a great friendship with Max

Beckmann, and there commenced a wonderful patronage that resulted in Lackner’s

ownership of 69 paintings by the artist, including 2 triptychs. Self-Portrait

with Horn was purchased in Paris in 1938 and remained the jewel in the crown of

Dr. Lackner’s collection until his death in December 2000.

In the book he wrote

on Beckmann, Dr. Lackner describes the work that he studied so closely and

faithfully in the more than fifty years that he owned it: “In Self-Portrait

with Horn, a very lonely man stares out of the canvas. The painting is among

the most melancholy, and perhaps the deepest, of Beckmann's many studies of his

own persona. The man does not look at himself in the mirror, nor at the

spectator before the canvas; his gaze follows the resonance of a horn call,

which he has just sent out like a message. He seems to listen for a distant

echo. But there is no response, only a great silence. Here is a man forsaken by

his time. No furnishings, no amenities of civilization, just an empty frame

remains behind him. His strange, timeless costume seems to combine harlequin

and convict associations. The richly colored stripes are a marvel of pure

painterly accomplishment, almost reverting to some organic phenomenon of

nature. Their rippling rhythm is reminiscent of sound waves; their full, soft

color corresponds to the timbre of the horn call.”

Christie's 2017

A visionary approach is also seen in the allegory of Max Beckmann’s political masterpiece Birds’ Hell (Hölle der Vögel) (1937-1938, estimate on request), a searing indictment of the Nazi Party and a personal outpouring of anguish kin to

Picasso’s Guernica (1937).

Birds’ Hell (Hölle der Vögel) is ‘an allegory of Nazi Germany. It is a direct attack on the cruelty and conformity that the National Socialist seizure of power brought to Beckmann’s homeland. Its place in Beckmann’s oeuvre corresponds to that occupied by Guernica in Picasso’s artistic development. It is an outcry as loud and as strident as an artistic Weltanschauung would permit. Not since his graphic attacks in

Hunger

and City Night

in the early twenties had Beckmann resorted to such directness, such undisguised social criticism. Birds’ Hell is Beckmann’s J’accuse’ (S. Lackner, Max Beckmann, New York, 1977, p. 130).

Christie's 2017

A visionary approach is also seen in the allegory of Max Beckmann’s political masterpiece Birds’ Hell (Hölle der Vögel) (1937-1938, estimate on request), a searing indictment of the Nazi Party and a personal outpouring of anguish kin to

Picasso’s Guernica (1937).

Birds’ Hell (Hölle der Vögel) is ‘an allegory of Nazi Germany. It is a direct attack on the cruelty and conformity that the National Socialist seizure of power brought to Beckmann’s homeland. Its place in Beckmann’s oeuvre corresponds to that occupied by Guernica in Picasso’s artistic development. It is an outcry as loud and as strident as an artistic Weltanschauung would permit. Not since his graphic attacks in

Hunger

and City Night

in the early twenties had Beckmann resorted to such directness, such undisguised social criticism. Birds’ Hell is Beckmann’s J’accuse’ (S. Lackner, Max Beckmann, New York, 1977, p. 130).

Max Beckmann’s Bird’s Hell (1938, estimate on request) will lead 20th Century at Christie’s, a series of sales that take place from 17 to 30 June 2017, in the Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale on

27 June 2017, when it will be offered at auction for the first time.

One of the most powerful paintings that Beckmann created while in exile

in Amsterdam it presents a searing and unforgettable vision of hell and

is poised to set a world record price for the artist at auction. Begun

in Amsterdam and completed in Paris at the end of 1938, this work ranks

amongst the clearest and most important anti-Nazi statements that the

artist ever made, mirroring the escalating violence, oppression and

terror of the National Socialist regime.

Painted with vigorous, almost gestural brushstrokes and bold, garish colours, Bird’s Hell envelops

the viewer in a sinister underworld in which monstrous bird-like

creatures are engaged in an evil ritual of torture. Presiding over the

scene is a multi-breasted bird who emerges from a pink egg in the centre

of the composition. To her right, a crouching black and yellow bird

looms over golden coins spread before him, while behind the central

figure, a group of naked women stand huddled together. Heightening the

sense of hysteria is the group of figures standing within a glowing,

blood red doorway to the left of the composition. Guarded by another

knife-wielding bird, they return the bird-woman’s gesture, their right

arms raised in unison in the same furious salute. At the front of the

scene, a naked man – the symbol of innocence within this reign of terror

– is shackled to a table, held down by another bird that is slashing

his back in careful, horizontal lines.

Continuing

the Germanic tradition of the depiction of hell, this painting echoes

the gruesome allegorical scenes of Hieronymus Bosch’s famed The Garden of Earthly Delights,

while at the same time, takes aspects of Classicism and mythology to

turn reality into a timeless evocation of human suffering. In this way, Bird’s Hell, like Pablo Picasso’s Guernica or

Max Ernst’s Fireside Angel of the same period, transcends the time and the political situation in which it was made to become a universal and singular symbol of humanity.

Max Ernst’s Fireside Angel of the same period, transcends the time and the political situation in which it was made to become a universal and singular symbol of humanity.

Sotheby's 2014

LOT SOLD. 1,025,000 USD

Sotheby's 2013

A canvas painted in New York by German Expressionist painter Max Beckmann (1884-1950) Vor dem Ball (Zwei Frauen mit Katze), or Before the Ball (Two Women with a Cat),

from 1949 and offered by a private party, is estimated to bring

$8-$12.8 million at Sotheby's Impressionist and modern art evening sale

on Feb. 5, 2013.

If the estimated price is achieved, it will put the painting among the top Beckmann canvases sold at auction, according to statistics from Artnet.com. His Self-portrait with Horn (1938) sold in 2001 at Sotheby's for $22.6 million; Self-portrait with Crystal Ball (1936) brought $16.8 million at Sotheby's in 2005; and Still Life with Gramophone and Irises (1924) went for $7.3 million at Christie's in 2007. Those are all oils on canvas, like Vor dem Ball, and slightly smaller than the 1949 work, which measures 56 by 39 inches.

If the estimated price is achieved, it will put the painting among the top Beckmann canvases sold at auction, according to statistics from Artnet.com. His Self-portrait with Horn (1938) sold in 2001 at Sotheby's for $22.6 million; Self-portrait with Crystal Ball (1936) brought $16.8 million at Sotheby's in 2005; and Still Life with Gramophone and Irises (1924) went for $7.3 million at Christie's in 2007. Those are all oils on canvas, like Vor dem Ball, and slightly smaller than the 1949 work, which measures 56 by 39 inches.

Christie's 2013

Christie's 2012