This fall, the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA) will present the first major exhibition in 50 years to explore the legacy and widespread influence of the revolutionary French painter Eugène Delacroix. “Delacroix’s Influence: The Rise of Modern Art from Cézanne to van Gogh” features 75 seminal paintings—including 30 works by Delacroix—to reveal the artist’s indelible impact on French painting and how his radical example led to the rise of modern art.

The exhibition also examines Delacroix’s role as mentor and archetype during his lifetime and how his work shaped the styles and predilections of many modern artists, including Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, Claude Monet, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir, among others. Organized in partnership with the National Gallery, London, “Delacroix’s Influence” will be on view at the MIA from October 18, 2015, through January 10, 2016, and draws on works from the MIA’s robust 19th-century holdings, as well as loans from 45 prestigious public and private collections worldwide.

“Eugène Delacroix was the very engine of revolution that helped transform French painting in the 19th century,” said Patrick Noon, the MIA’s Patrick and Aimee Butler Curator and Chair of Paintings, and organizing curator of the exhibition. “Kept at arm’s length by the Académie des Beaux-Arts, he was an artist who was truly ahead of his time, whose work and critical writings resonated deeply with his peers and helped shape the trajectory of art history. This exhibition will examine Delacroix as the bridge—in practice and in theory—between Anglo-French Romanticism and Impressionism.”

“Delacroix’s Influence” demonstrates how Delacroix redefined the possibilities of capturing the unique interplay between light and form, as well as his fascination with optical effects, bold use of color, and passion for the exotic. These innovations subsequently inspired the spontaneity of the Impressionists, the dreamlike allusion of the Symbolists, and the saturated color palette made famous almost a century later by such artists as Renoir and Matisse.

Organized according to four thematic sections—Emulation; Orientalism: Imagined/Experienced/Re-Imagined; Narrative Painting at a Crossroads: ‘Truth in Art’; and Delacroix’s Legacy: In Paint and Prose—the exhibition features a broad swath of paintings by Delacroix and his admirers, including works by Cézanne, Degas, Gauguin, van Gogh, Kandinsky, Manet, Matisse, Monet, Redon, Renoir, and Signac, among others.

Notable works in the exhibition include:

• Delacroix’s Convulsionists of Tangier (1837-38), widely considered one of the artist’s foremost masterworks and a cornerstone of the MIA’s 19th-century collection. The painting depicts a frenzied scene that Delacroix witnessed during his travels to North Africa in 1832, in which members of the Aïssaouas, a fanatical Muslim sect, crowd the streets. Delacroix’s use of vivid colors and vigorous brushstrokes represent the artist’s signature style and ability to expertly capture the turmoil and urgency of his subject.

• Delacroix’s Lion Hunt (1861), one of three Lion Hunt paintings Delacroix produced for dealers and private collectors between 1855 and 1861. This final picture differs markedly in its spatial definition from the flat composition of the earlier pictures—capturing a greater sense of depth and clearly articulated narrative while also maintaining intense and expressive brushwork.

• Édouard Manet’s Music in the Tuileries Gardens (1862), the artist’s first major work depicting modern urban life. The painting features a band playing for a fashionable crowd that includes several portraits of Manet’s friends—the poet Baudelaire, painter Henri Fantin-Latour, poet and novelist Théophile Gautier, and composer Jacques Offenbach—as well as his brother, Eugène, and the artist himself. To capture these portraits, Manet used photographs as his source of imagery, a technique often employed by Delacroix to underscore a distinct contemporary sensibility in his work.

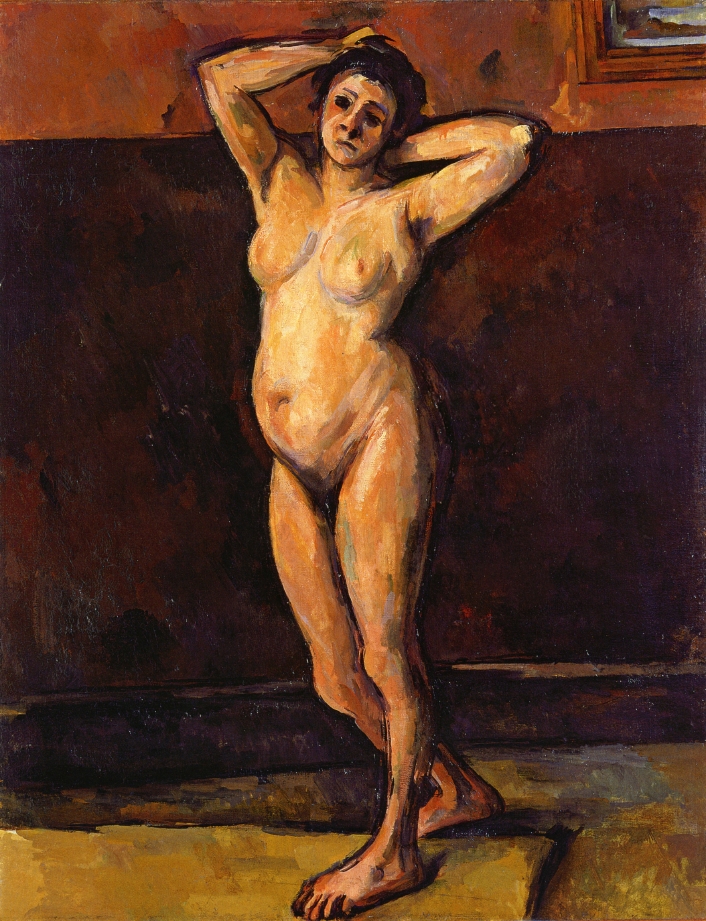

• Paul Cézanne’s Standing Nude (c. 1898), a representation of a nude in an interior setting that evokes the traditional theme of a woman or goddess at her toilet. Although Cézanne frequently depicted female bathers in an outdoor landscape, the artist admired Delacroix’s The Morning Toilet (or Woman Combing Her Hair) (1850), which he copied shortly after it was exhibited in the 1885 Delacroix retrospective at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

• Paul Gauguin’s Christ in the Garden of Olives (1889), one of several religiously inspired paintings Gauguin created, in which a vulnerable Christ is depicted in isolation prior to his impending martyrdom—a pose derived from Delacroix’s Christ Shown to the People (1850). The work’s dark colors and gloomy tonality severely contrast against Christ’s flaming hair, further emphasizing the sense of alienation in this overt personification of the artist.

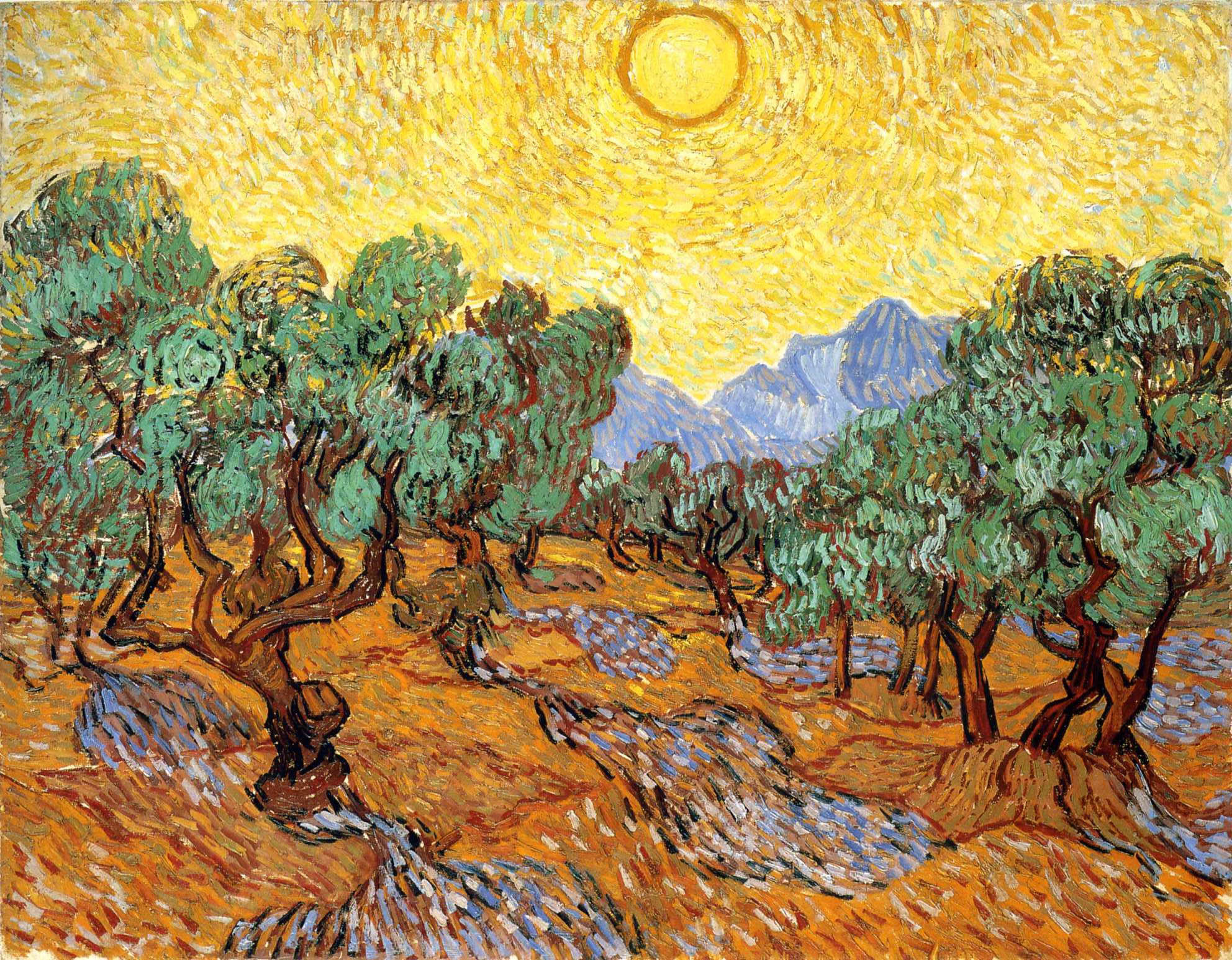

• Van Gogh’s Olive Trees (1889), one of 15 canvases of olive trees van Gogh created while housed in the asylum of St-Paul in St-Rémy in southern France. In his correspondence with his brother, van Gogh wrote of the olive tree: “It’s too beautiful for me to dare paint it or be able to form an idea of it…if you want to compare it to something, [it is] like Delacroix.” It was during this period that the artist created many of his most renowned works, and the vibrant yellow and orange hues in this painting suggest it was produced during the autumn.

• Odilon Redon’s Pegasus and the Hydra (1905), one of several depictions of ancient myths showcasing the artist’s increasing fascination with monster slayers. Influenced by Delacroix’s treatment of similar subjects—in this case, his Apollo Slaying Python (1851)—Redon conceived this work as a metaphor for the artist as an ostracized genius eventually vanquishing chaos and adversity.

Delacroix’s posthumous influence persisted undiminished for nearly five decades and over several generations of avant-garde artists, each of whom, however divergent their own aesthetic programs, discovered something of value in the legendary artist’s oeuvre and dynamic personality. Impressionists, Post-Impressionists, Neo-Impressionists, Symbolists, and Fauves borrowed Delacroix’s ideas as deduced from his varied and accessible painted works and profuse writings.

“Delacroix’s Influence: The Rise of Modern Art from Cézanne to van Gogh” is co-organized with the National Gallery, London, where it will be on view from February 10 through May 15, 2016.

The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalogue, which comprises lead essays by Patrick Noon, Curator and Chair of Paintings at the MIA and organizing curator of the exhibition, and Christopher Riopelle, Curator of Post-1800 Paintings at the National Gallery, London.

About Delacroix:

Orphaned at the age of sixteen, Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) quickly abandoned his classical academic training at the Lycée Impérial in favor of self-study. He gleaned early insight and direction by copying old master works in the Musée du Louvre, as well as from his friendship with Théodore Géricault, a pioneer of the Romantic movement in French painting. Géricault, who advocated for individual over formulaic expression, profoundly influenced the development of Delacroix’s first publicly exhibited painting, Barque of Dante (1822), which was celebrated for its acute sentiment and imaginative composition. The work was immediately acquired for the Luxembourg Palace— establishing him as the next prodigy of French Romanticism—and became the most copied of Delacroix’s paintings during the 19th century.

By the time of his death, Delacroix had established himself as a champion of the avant-garde and was one of the most revered artists in Paris. His paintings continued to be distinguished by their expressive, improvisational brush strokes, which challenged the traditional techniques and attitudes of the period’s preeminent Grand Style and paved the way for younger artists’ stylistic experimentation and creative innovation.

From an excellent review in Mpls.St.Paul Magazine (Images added):

In the first gallery alone—a section called Emulation—are paintings by Cezanne, Manet, Gaugin, Sargent, and several others, all arranged around the exhibition’s signature painting, a rare self-portrait of Delacroix himself. Among these are Manet’s famous Music in the Tuileries Gardens, as well as a remarkable copy of

Delacroix’s The Jewish Wedding in Morocco

done as an exercise by Renoir to tease out some of the Master’s secrets.

The following section, Orientalism, explores Delocroix’s travels to North Africa and other artists’ fascination with this new territory, recently colonized by the French.

Among the delights to be found here are

Delacroix’s Combat of the Giaour, a classic horses-in-the-heat-of-battle painting,

and The Convulsionists of Tangier, a familiar painting from Mia’s collection. Both evoke the furious energy and violence that mesmerized painters in Paris, convincing many of them to travel to Morocco in order to experience for themselves the quality of the sun in that part of the world, as well as the barbarity that, if Delacroix’s paintings were to be believed, apparently ran amok in the streets there.

From another good review:

The very last painting Delacroix painted before his death in 1863, “Arabs Skirmishing in the Mountains.”

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)