San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, June 24–October 9, 2017

The Met Breuer, New York, November 14, 2017–February 4, 2018

Munch Museum, Oslo, May 12–September 9, 2018

Edvard Munch, Self-Portrait: Between the Clock and the Bed, 1940–43; oil on canvas; 58 7/8 x 47 7/16 in. (149.5 x 120.5 cm); photo: courtesy the Munch Museum, Oslo

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA) has opened the exhibition Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed, on view June 24 through October 9, 2017. Featuring approximately 45 paintings produced between the 1880s and the 1940s, with seven on view in the United States for the first time, this exhibition uses the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch’s last significant self-portrait as a starting point to reassess his entire career.

Organized by SFMOMA, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and the Munch Museum, Oslo, Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed brings together Munch’s most profoundly human and technically daring compositions of love, despair, desire and death, as well as more than a dozen of his self-portraits to reveal a singular modern artist, one who is largely unknown to American audiences, and increasingly recognized as one of the foremost innovators of figurative painting in the 20th century.

“When you consider that Munch felt that he didn’t really hit his stride until his 50s and that his career doesn’t map against traditional paths of art history, then the latter part of his career warrants a closer look,” said Gary Garrels, Elise S. Haas Senior Curator of Painting and Sculpture at SFMOMA. “Munch’s influence can be felt in the work of many artists such as Georg Baselitz, Marlene Dumas, Katharina Grosse, Asger Jorn, Bridget Riley and particularly Jasper Johns, who became fascinated by the cross hatch patterns in Munch’s Self-Portrait. Between the Clock and the Bed.”

“Munch really presents an alternative to the traditional school-of-Paris-driven history of modernism that has long been dominant, but tells an incomplete account of the art of the past century,” added Caitlin Haskell, associate curator of painting and sculpture at SFMOMA.

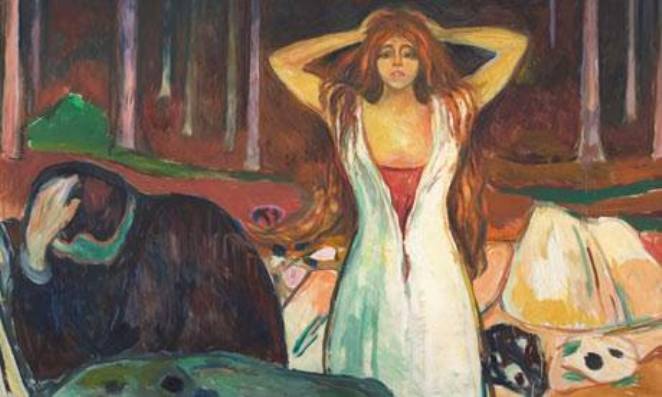

Seven works in the exhibition make their United States debut including

Lady in Black (1891),

Puberty (1894),

Jealousy (1907),

Death Struggle (1915),

Man with Bronchitis (1920),

Self-Portrait with Hands in Pockets (1925–26)

and Ashes (1925).

The exhibition will also include an extraordinary presentation of

Sick Mood at Sunset. Despair (1892),

the earliest depiction and compositional genesis of

The Scream, which is being shown outside of Europe for only the second time in its history.

About the Exhibition

As a young man in the late 19th century, Edvard Munch’s (1863–1944) bohemian pictures placed him among the most celebrated and controversial artists of his generation. But as he confessed in 1939, his true “breakthrough came very late in life, really only starting when I was 50 years old.”

'

One of Munch’s last works, Self-Portrait. Between the Clock and the Bed (1940–43) — with its themes of desire, mortality, isolation and anxiety — serves as a touchstone and guide to the approximately 45 works in the exhibition. Together, these paintings propose an alternative view of Munch as an artist as revolutionary in the 20th century as he was when he made a name for himself in the Symbolist era.

Born and raised in Kristiania (now Oslo), Norway, Edvard Munch’s career spanned 60 years and included ties to the Symbolist and expressionist movements, as well as their legacies. Following a brief period of formal training in painting at the Royal School of Art and Design in Kristiania, Munch exhibited widely throughout Europe affecting the trajectory of modernism in France, Germany and his native Norway. While best known for the paintings and prints titled The Scream, Munch was a prolific creator who left a body of work that includes approximately 1,750 paintings, 18,000 prints and 4,500 watercolors as well as sculpture, graphic art, theater design and film.

Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed unfolds in eight thematically-focused galleries that explore Munch’s long-term engagement with particular subjects that recur throughout his career — love, death, sickness, psychological turmoil and mortality, especially his own. The paintings on view, many deeply personal works from Munch’s own collection now held by the Munch Museum, as well as loans from institutions and private lenders from around the world, also demonstrate Munch’s liberated, self-assured painting style and technical abilities including bravura brushwork, innovative compositional structures, the incorporation of visceral scratches and marks on the canvas and his exceptional use of intense, vibrant color.

The exhibition begins with a double gallery of self-portraits featuring works created between the 1880s and 1940s that follow the artist’s path from a self-conscious young man with the future ahead of him to an elderly painter whose time is nearing an end. But for all of their confessional qualities, the paintings are not simply documentary. Perhaps more than any artist of his time, Munch also uses the self-portrait to fictionalize his personal narrative. In

Self-Portrait with Spanish Flu (1919),

a painting that appears in a later gallery, Munch depicts himself as suffering from the illness though later research suggests that he may never have had it and instead sought to ingratiate himself with the Norwegian public. From this opening gallery, the exhibition progresses through galleries devoted to inner turmoil, jealousy, scenes of the artist in his studio, illness, death and romantic love.

The works in the exhibition also demonstrate the progression of Munch’s technique from an early

Self-Portrait (1886) with its thick impasto and chipped away dry paint, to

Self-Portrait with Cigarette (1895),

an example of a “turpentine painting” in which Munch uses heavily diluted oil paint and a flat brush to create an ethereal, smoky glaze that allows the white ground of the canvas to become part of the painted surface. This technique, not typical to the 1890s, incorporates some of the strategies of watercolor painting, using the canvas color as a constructive element and part of the composition.

“Munch was an artist who never stopped looking. Never stopped feeling. Some people think the first part of his career is the classic Munch, and the best. But he’s, in a way, challenging these kinds of simple conclusions. He never stopped processing his own art and often did new versions of some of his most central motifs, referencing his own art into his late years,” explained Jon-Ove Steihaug, director of exhibitions and collections at the Munch Museum.

Illustrating Munch’s restless revisiting of themes and his skill as an observer of human nature, the final painting in the exhibition,

The Dance of Life (1925),

reworks

a picture of the same title The Dance of Life (1899) that was part of the monumental cycle The Frieze of Life.

In total, the exhibition contains seven scenes from this series, which offers visitors a metaphoric “dance” across many of Munch’s key themes — attraction, love, jealousy, rejection — and culminates in a poetic meditation on the joys and sorrows that define a life.

Exhibition Organization and Support

Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed is organized by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Munch Museum, Oslo.

The exhibition is curated by Gary Garrels, Elise S. Haas Senior Curator of Painting and Sculpture at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Sheena Wagstaff, Leonard A. Lauder Chairman, Department of Modern and Contemporary Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and Jon-Ove Steihaug, director of exhibitions and collections at the Munch Museum, Oslo, with Caitlin Haskell, associate curator of painting and sculpture at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

Exhibition Catalogue

A fully illustrated catalogue, Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed, will accompany the exhibition. Edited by Gary Garrels, Jon-Ove Steihaug and Sheena Wagstaff, the catalogue includes a foreword by celebrated Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgaard. It includes essays by Patricia Berman, Theodora L. and Stanley H. Feldberg Professor of Art at Wellesley College; Allison Morehead, associate professor at Queen’s University, Ontario; Richard Shiff, Effie Marie Cain Regents Chair in Art at the University of Texas at Austin; and Mille Stein, paintings conservator emerita at the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU). The catalogue is published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and distributed by Yale University Press.

_by_Edvard_Munch.jpg/1200px-Puberty_(1894-95)_by_Edvard_Munch.jpg)