David Hockney, Howard Hodgkin and Peter Blake were all part of the same

stellar generation of British artists as well as lifelong friends – with

Blake and Hodgkin even visiting Hockney in Los Angeles in 1979.

David Hockney, Study for Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), coloured crayon on paper, 1972 (est. £100,000-150,000)

Study for Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) – which features on the cover of the catalogue for the current David Hockney retrospective at Tate Britain.

Completed in 1972 following the devastating end of a five year relationship with his first-love Peter Schlesinger, Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) shows a fully dressed Schlesinger standing at the edge of the pool gazing at a submerged figure swimming underwater. Originally derived from the accidental juxtaposition of two photographs on his studio floor, the work reveals the parallel intimacy and distance between the couple. This preparatory study is a riveting artefact of the artist’s working process – giving an intimate insight into the creation of an irrefutable masterwork. Each perfectly placed pencil stroke reveals the artists hand, how he was experimenting and what he was concentrating on. There is a delicate balance and haunting juxtaposition between the joy of the swimmer gliding forward – with his arms stretched forwards in anticipation yet entrapped by the weight of the water – and the imposing dominance of the clothed figure standing sentinel. On closer inspection, there is a slight alteration in the position of the vulnerable swimmer from this work to the final version, the sketch portraying a greater ambiguity where the pose can be interpreted as either optimistic or struggling.

Hockney had begun the painting in October 1971, as documented in great detail in Jack Hazan’s semi-fictional documentary A Bigger Splash. It is likely that Hockney made this fresh and vivid drawing on a visit to Le Nid du Duc in early April 1972, sketching only a harsh outline for the standing figure as Schlesinger was not available to pose. Le Nid du Duc was director Tony Richardson’s house in the South of France, a bolthole for London artists who were free to indulge themselves in a utopian lifestyle that almost approached the blissful domesticity that Hockney had fallen for in Los Angeles.

The ripples and flickers of the water demonstrate one of Hockney’s primary concerns in his swimming pool pictures, as he stated that part of his interest lay in the fact that ‘it is a formal problem to represent water, to describe water, because it can be anything. It can be any colour and it has no set visual description.’

Another study:

Howard Hodgkin, After Dinner at Smith Square, oil on board in Artist’s frame, 1980-1 (est. £150,000-250,000)

Also currently the subject of a major retrospective exhibition in London, in Hodgkin’s abstract works of art specific personal memories find expression in sumptuous colour-saturated brushwork. After Dinner at Smith Square is the sequel to a painting in the collection of the Tate and currently on view at the Absent Friends exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, London. The subjects of both works are the collectors Robert and Lisa Sainsbury, who were close friends of the artist. The couple enjoyed building friendships with artists, often supporting their early careers, and together amassed an eclectic collection that contains over a thousand items spanning 5000 years – now housed at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, Norwich. Upon discovering that he was working on this piece, the Sainsburys frequently invited him to dinner to refresh his memory of the scene, on one occasion also posing so that he could make preparatory drawings – an unusual occurrence given that Hodgkin so rarely made studies of the sitters for his portraits. A celebratory painting, Hodgkin captures the Sainsburys in rich, resplendent tones, talking to each other below a small painting by Bonnard.

Sir Peter Blake, Venuses’ Outing to Weymouth, oil on canvas, 1994-2004 (est. £80,000-120,000)

In 1993, Blake was invited to become artist in residence at the National Gallery in London, with the aim of creating a new body of work in response to the Gallery’s collection. Blake was the perfect contemporary artist for this project due to his interest in art history, and holds both Elvis Presley and Hans Holbein in equal esteem. Blake walked through the sixty-six rooms of the gallery in three hours, wandering past each and every painting, when the idea emerged to bringing together all the great Venuses of the collection, from Botticelli and Titian to Velazquez. In this painting he takes the Venuses on a daytrip to John Constable’s Weymouth Bay for a spot of sunbathing in the nude. In the background Folly from Bronzino’s Allegory with Venus and Cupid is engaged in a game of beach cricket with a cupid.

The setting is not just whimsical, as Weymouth Bay was where Constable spent his honeymoon after a difficult relationship with his future father-in-law – here, he brings together art history’s most wellknown goddesses of love for a triumphal day trip. This witty response to the nation’s treasure trove of art history encapsulates Blake’s charm and was a favourite when exhibited as part of his Tate Liverpool retrospective in 2007.

‘A NEST OF GENTLE ARTISTS’: HAMPSTEAD IN THE 1930s

'A nest of gentle artists' was a phrase coined by the art historian Herbert Read to describe a group of internationally important artists who lived and worked in Hampstead – which had become the epicentre of avant-garde in the 1930s.

Dame Barbara Hepworth, Standing Figure, marble, executed in 1934, the present work is unique (est. £500,000-800,000)

Carved in the pivotal year of 1934, this rare and intimate sculpture encapsulates all that was most important to Hepworth during the early 1930s and was once kept in the collection of her parents. The figure stands poised between abstraction and figuration, with all direct reference to the human form reduced elegantly to a single point on the figure’s head. The subtle contours of the body, beautifully curving around the white marble which in turn demonstrates her virtuosity as a carver as well as her profound understanding of the human figure. The importance of artist’s hand was crucial to her work and she was later known for forbidding the use of any mechanical tools in her studio. Hepworth gave birth to triplets on 3 October of the same year, and once she was able to start carving again that November, the subtle yet sophisticated references to the human figure evident in Standing Figure disappeared altogether as moved into the realm of complete abstraction. Drawing on the powerful dialogue with abstraction developed by Brancusi, along with the minimalist forms of prehistoric Cycladic examples, this work positions Hepworth at the very heart of the European avant-garde.

Ben Nicholson, Two Fishes, oil and pencil on canvas, laid on board, 1932 (est. £250,000-350,000)

This rediscovered poetic still-life gives an intimate insight into Ben Nicholson’s life; his interest and his artistic connections – from his father William Nicholson to Georges Braque, and the Parisian avant-garde.

The first owner of Two Fishes was the artist Edward Wadsworth, who once stated that Nicholson was ‘essentially exquisite and elegant’4 with his pared back compositions. Inspired by regular visits to France throughout the year in which this was painted, Nicholson absorbed elements of Synthetic cubism – when artists started adding textures and patterns to their paintings, experimenting with collage using newspaper print and patterned paper. The roughly textured surface and flattened pictorial also draws inspiration from the Russian avant-garde who had emigrated to Paris in the wake of the Revolution. Nicholson was a devoted follower of tennis, often found bouncing a ball along the streets of St. Ives, and in this work a copy of Le Journal is depicted reporting on Henri Cochot’s loss to his greatest rival during the Davis Cup. Cochot was one of the leading French players of the period, having won Wimbledon twice and ranked world number one from 1928 to 1931. However, 1932 was an inauspicious year for the athlete and this works signals the beginning of the end for his stellar career.

Naum Gabo, Linear Construction in Space No.1, Variation, circa 1950 (est. £150,000-250,000)

Linear Construction in Space No.1 encapsulates Naum Gabo’s constant quest to expand the boundaries of sculpture. Driven in part by his Constructivist enchantment with industry and the modern world, Gabo used man-made substances as opposed to the traditional sculptor’s mediums of stone, wood or bronze. Using the hard but translucent Perspex as a frame, he was able to fill space using reflective nylon filaments stretched across a void to create the impression of a continuous form. Thus he replaced the mass and bulk of conventional sculpture with illusory volume – an emptiness filed with light and movement. The impetus for this work was a public sculpture that was never completed, due to commemorate the skill of the works of a textile factory. Gabo was an idealist when it came to the role that art should play in society, believing that public sculpture should be used to celebrate the achievements of working people in today’s industrialised world. Other versions of this model are housed in museums such as the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Tate Gallery, London and The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C. among others.

MOORE AS DRAUGHTSMAN

Henry Moore, Two Standing Figures, pencil, wax crayon, watercolour, pen and ink and wash on paper, 1940 (est. £200,000 – 300,000)

As a consummate and innovative draughtsman, Moore believed that a sculptor’s drawings should – through the suggestion of background and evocation of atmosphere – be more than mere diagrams or studies. Many of these drawings were a means to generate ideas that later became sculptures, but are also important works within their own right. Three impressive examples from a Private American Collection are offered in this sale, celebrating Moore’s brilliance as a draughtsman.

LIFE IN LONDON

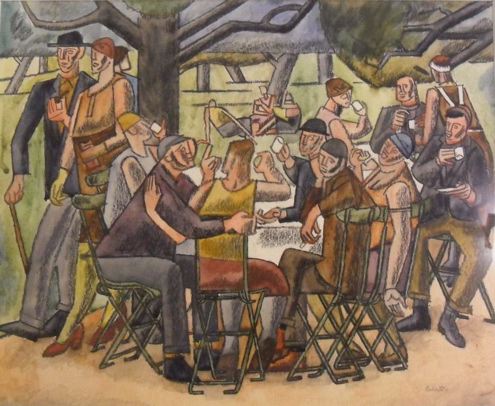

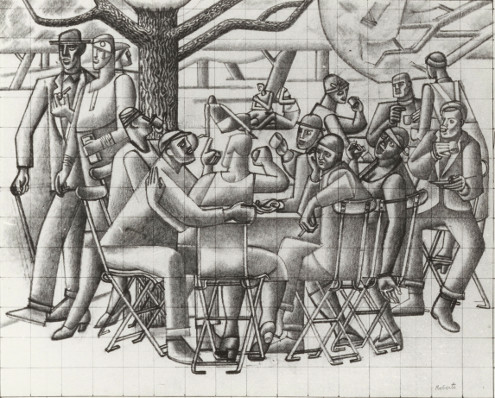

William Roberts, The Tea Garden, oil on canvas, 1928 (est. £250,000-350,000)

William Roberts felt it rang false to purely invent a subject, and would spend most of his days walking and observing in London – jotting down sketches on individual scraps of paper that went on a pile that built up over the years. Unseen since the 1920s, The Tea Garden is perhaps derived from such an expedition, focusing on the tumultuous energy of modern life with a lovely documentary quality. Following the war, the active breaking of social restrictions meant that there was always a spectacle on view, and Roberts’ taste for these raucous scenes only intensified. This painting also displays his particular interest in the humorous clash of classes one increasingly found in public settings, with an elegantly dressed couple taking notice of the rather brash crowd they are strolling alongside. Roberts had a keen eye of detail and his distinctive style articulates the intricacies of human interaction through gesture and facial expression.

Typical of the artist’s method, several intricate preparatory drawings for The Tea Garden exist, now in the collections of institutions including the Tate, London.

PORTRAITURE

Frank Auerbach, Head of JYM III, oil on board, 1981 (est. £400,000-600,000)

Head of JYM III is the ultimate example of the dramatic innovations that Auerbach brought to portraiture, that most traditional of artistic genres. Throughout his career, the artist pursued the same subjects, close friends and admirers of his work, and none more so than Juliet Yardley Mills - who posed for him from 1956 until she was aged eighty in 1997. The task of siting for Auerbach was no easy feat and JYM arrived every Wednesday and Sunday having taken two buses from her home in southeast London and would sustain awkward poses for four hours and more. The immediate force and vigour of execution of this work demonstrates Auerbach’s intimate psychological response to his subjects, as a bold silhouette emerges amid swathes of dramatic brushwork on a sculptural surface that was reworked time and time again.