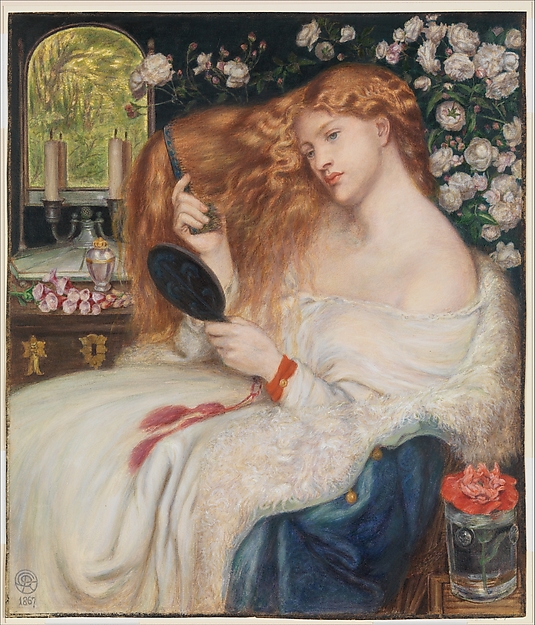

In July this year, Sotheby’s will offer the only version of one of the most iconic works by Dante Gabriel Rossetti to remain in private hands. A celebration of the beauty of the artist’s first mistress, Fanny Cornforth, and a pictorial hymn to her glorious corn-gold hair,

Lady Lilith comes to auction for the first time in thirty years.

The work was painted during Rossetti’s most innovative period in the 1860s, when he created the cult of the Pre-Raphaelite beauty, or ‘Stunner’ as he called them, whose physical qualities were embodied by Fanny Cornforth. Two other paintings of Lady Lilith were produced by Rossetti during this decade and they now hang in museums in the US.

The rediscovered picture will be offered at Sotheby’s London sale of Victorian, Pre-Raphaelite & British Impressionist Arton 13 July with an estimate of £400,000-600,000.2LadyLilith(Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington)Fanny CornforthSimon Toll, Sotheby’s Victorian Art Specialist, said:

“Rossetti’s work is a great passion of mine and I have been lucky enough to bring to auctionseveral important examples by him in recent years, breaking the world record for a watercolour, a drawing and an oil painting. ‘Lady Lilith’ has always been one of my favourites but Ihad never seen this particular picture‘in the flesh’. It was a moment of genuine excitement when I first saw itbeing unwrapped from the packing case in which it had been sent from Japan, its home for the last thirty years. Not only is the work in wonderful condition, it’s also in Rossetti’s original frame and with the artist’s hand-written poem attached to the backing-board. To find a picture in such an untouched conditionis exceptionally rare.”Rossetti met Fanny Cornforth (1835-1906) during the summer of 1856, apparently at a procession celebrating the return of soldiersfrom the Crimean war. In one of the many stories concerning their first meeting, Rossetti ‘accidently’ undid her hair in a restaurant –a gesture both provocative and intimate. Based upon the evidence of his paintings of Fanny alone, there can be little doubt of the physical nature of their relationship. Pairing the subject of Lilith with Fanny was no coincidence: Fanny was most likely the first woman that Rossetti slept with and Lilith was the first woman, created from the same earth as Adam before the creation of Eve.

Rossetti described Lilith as being ‘the first gold’, and it seems that this is how he regarded Fanny.The daughter of a Sussex blacksmith, Fanny Cornforthwas born Sarah Cox. Though coarse, ill-educated and light-fingered, Fanny had a deep well of affection, a wonderful sense of humour and an open-mindedness which must have been refreshing to Rossetti. With her sensuality, her sense of fun and a mass of golden hair that reached the ground, she offered him an energetic antidote to the ailing fragility of his future wife Lizzie Siddal, from whom he was separated at the time he met Fanny.

During the ten years of the artist’s protracted engagement with Lizzie, it is thought that their relationship was never consummated. After Lizzie’s suicide in 1862, Fanny moved into Rossetti’sstudio to be his ‘housekeeper’. Though he developed infatuations for other women as Fanny’s golden beauty faded, Rossetti never abandoned her, even remaining close through her two marriages and supporting her with money and possessions during times of financial difficulty. In 1882, Rossetti wrote to Fanny pleading for her to come to his death-bed. His circle of friends cruelly chose not to deliver his pleas and she was only told of Rossetti’s death days after his funeral.Rossetti began the first version of

Lady Lilith, 1866-68 (altered 1872-73)

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828-1882)

Oil on canvas, 38 x 33 1/2 inches

Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935

Lady Lilith (Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington), a large oil on canvas, in 1864 as the first commission for Frederick Richards Leyland, who would become the artist’s greatest patron. Leyland disliked the way Rossetti had painted Lilith’s face and asked him to scrape it out and repaint it with a different model –an event that many scholars consider one of the greatest Pre-Raphaelite travesties.

Fortunately Rossetti had made two watercolour replicas of Lady Lilith before the repainting was undertaken, both of them in 1867, the year the oil was completed in its original form.

One of these, made for the collector William Coltart, hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, whilst the other, made for Alexander Stevenson, is the version to be offered for sale.

Fanny was devastated when she learnt that her face had been obliterated from the oil version in 1872, to be replaced by the face of a professional model named Alexa Wilding, whose flame-red beauty ignited her jealousy. Rossetti tried to keep the news of what he had done to Lady Lilithfrom Fanny, knowing that she would be upset by having the celebration of her beauty destroyed in such a way. Fanny claimed that when he had removed her face from the picture, he sat down and wept “until the tears ran through his fingers, and said ‘I can’t do it over again, and you are not what you were!’”[letterfrom Fanny to the American art collector Samuel Bancroft, 18 August 1908].

Though prone to exaggeration, there may be some truth to Fanny’s remarks –by the 1870s, her youthful buxom charm had been replaced by a more expansively matronly heaviness. Fanny did not pose for another painting by Rossetti, although she did eventually forgive him for his slight. Rossetti perhaps felt guilty about acquiescing to his patron’s wishes and altering a picture so drastically.

In a letter to Ford Madox Brown he wrote,‘he [Leyland] has every reason to be pleased with the way I have worked for him lately... I have often said that to be an artist is just the same thing as being a whore, as far as dependence on the whims and fancies of individuals is concerned.’

The subject of Lilith can be found in Babylonian mythology from the 3rd and 4th centuries and was retold in Hebrew scripture. In a variation of her story from the 13th century, Lilith had refused to be subservient to Adam, abandoned the Garden of Eden, and coupled with the archangel Samael. By the 19th century the name Lilith had become synonymous with powerful female independence and primordial sexual allure –the original femme fatale.

In a letter to his doctor dated 21 April 1870, Rossetti made it clear that his intention had been to paint a picture that ‘represents a Modern Lilith combing out her abundant golden hair and gazing on herself in the glass with that self-absorption by whose strange fascination such natures draw others within their circle.’

In

Lady Lilith, Rossetti presents a remarkably intimate depiction of a woman only partially

dressed in her night-gown or under-dress with her hair loose on her shoulders.

In the 19th century, such frank observations of the bedroom activities that

would only be witnessed by a lover would have been considered shockingly

modern. Even the flowers in the picture are laden with symbolism and erotic

suggestion –the roses have an almost fleshy voluptuousness and whilst their

colour suggests purity, their showy exuberance seems to be more indicative of fulfillment.

The red flower in the foreground –possibly a poppy –plucked and contained in a

vase may represent the de-flowered ‘kept woman’. The only allusion to Lilith’s

malignancy is the poison digitalis on her dresser beside a pot of hair oil and

a mirror that reflects the view of the Garden of Eden.