June 4–August 27, 2017

Picasso: Encounters, on view at the Clark Art Institute June 4–August 27, investigates how Pablo Picasso’s (1881–1973) creative collaborations fueled and strengthened his art, challenging the notion of Picasso as an artist alone with his craft. The exhibition addresses his full stylistic range, the narrative themes that drove his creative process, the often-neglected issue of the collaboration inherent in print production, and the muses that inspired him, including Fernande Olivier, Olga Khokhlova, Marie-Thérèse Walter, Dora Maar, Françoise Gilot, and Jacqueline Roque.

Organized by the Clark with the exceptional support of the Musée national Picasso–Paris, Picasso: Encounters is comprised of thirty-five large-scale prints from private and public collections and three paintings including his seminal

Self-Portrait (end of 1901)

and the renowned Portrait of Dora Maar (1937),

both on loan from the Musée national Picasso–Paris.

The exhibition begins with a painting from Picasso’s Blue Period

(1901–1904). Self-Portrait embodies the despair, isolation, and poverty

that marked images created during this period. Following this, visitors

encounter

The Frugal Repast (1904) which was the artist’s first foray into large-scale printmaking, and was created at the end of the Blue Period. Picasso was living with his lover Fernande Olivier in Montmartre, a bohemian section of Paris, creating art that depicted individuals at the margins of society, such as the poor. The impression shown in this exhibition ––one of only two works by Picasso in the Clark’s permanent collection ––was printed by Eugène Delâtre (1864–1938), an artist and printer known to add his own creative touches to other artists’ prints. Delâtre’s hand is evident in this printing in the inky areas of tone on the plate, which gave texture and depth absent in later printings. Picasso did not utilize Delâtre when the publisher Ambroise Vollard (1866–1939) re-issued the print, perhaps indicating his displeasure with the printer’s interpretation.

The Frugal Repast (1904) which was the artist’s first foray into large-scale printmaking, and was created at the end of the Blue Period. Picasso was living with his lover Fernande Olivier in Montmartre, a bohemian section of Paris, creating art that depicted individuals at the margins of society, such as the poor. The impression shown in this exhibition ––one of only two works by Picasso in the Clark’s permanent collection ––was printed by Eugène Delâtre (1864–1938), an artist and printer known to add his own creative touches to other artists’ prints. Delâtre’s hand is evident in this printing in the inky areas of tone on the plate, which gave texture and depth absent in later printings. Picasso did not utilize Delâtre when the publisher Ambroise Vollard (1866–1939) re-issued the print, perhaps indicating his displeasure with the printer’s interpretation.

While still living in Montmartre, Picasso worked with the French artist

Georges Braque to co-invent Cubism. Picasso created a handful of Cubist

prints, the most important being

Still-Life with Bottle of Marc (1912). The composition includes fragments of a bottle, as well as drinking glasses and cards. The playing cards at the bottom half of the print, including the ace of hearts, have been said to signify Picasso’s new lover, Eva Gouel. The print was commissioned by the German dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, probably as a way to market Picasso to a wider audience through the dissemination of prints.

Still-Life with Bottle of Marc (1912). The composition includes fragments of a bottle, as well as drinking glasses and cards. The playing cards at the bottom half of the print, including the ace of hearts, have been said to signify Picasso’s new lover, Eva Gouel. The print was commissioned by the German dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, probably as a way to market Picasso to a wider audience through the dissemination of prints.

Following World War I, Picasso became involved in theater design. It was

through this interest that he met his first wife, the Russian dancer

Olga Khokhlova, who performed in the corps of the Ballets Russes. The

couple moved to a fashionable neighborhood in Paris where they began to

entertain and mingle with the elite, a changed atmosphere from Picasso’s

earlier bohemian circles. The artist’s upward mobility, both in the art

market and in the sophisticated lifestyle he shared with Khokhlova,

began to appear in his art. The drypoint

Portrait of Olga in a Fur Collar (1923) depicts Olga dressed in the height of fashion, serenely turning her head to the side.

Portrait of Olga in a Fur Collar (1923) depicts Olga dressed in the height of fashion, serenely turning her head to the side.

Marie-Thérèse Walter and The Minotaur

In 1927, Picasso met one of the most iconic muses of his artistic

career, Marie-Thérèse Walter. Walter would become both an erotic and

visual preoccupation for Picasso during an immensely productive time in

his life. Her youth and classical beauty are evident in

Visage (Face of Marie-Thérèse) (1928), which was created for a monograph on the artist by the Parisian collector and critic André Level.

Visage (Face of Marie-Thérèse) (1928), which was created for a monograph on the artist by the Parisian collector and critic André Level.

The numerous manifestations of Walter in other Picasso prints of the

1930s are less portrait-like than Visage; she frequently appears as a

thematic inspiration. During this time, Picasso’s imagery focused on

classical mythology and bullfighting.

In Minotauromachia (1935), the minotaur charges at a horse carrying a likeness of Marie-Thérèse Walter. Above the scene, two female spectators who resemble Walter peer out from the arched window of a tower with a dove perched on the sill. A young girl below them holds a candle. Her innocence, demonstrated by the purity of light, blinds the minotaur and halts him in his quest.

Picasso Prints: The Vollard Suite at the British Museum

In The Vollard Suite, printed by Picasso’s frequent collaborator Roger Lacourière (1892–1966), male minotaurs, fauns, and bulls enact creative or sexual fantasies with the objects of their desire—female mythical creatures or humans.In Minotauromachia (1935), the minotaur charges at a horse carrying a likeness of Marie-Thérèse Walter. Above the scene, two female spectators who resemble Walter peer out from the arched window of a tower with a dove perched on the sill. A young girl below them holds a candle. Her innocence, demonstrated by the purity of light, blinds the minotaur and halts him in his quest.

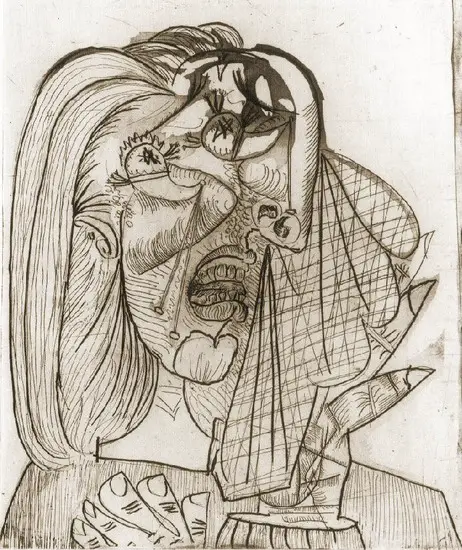

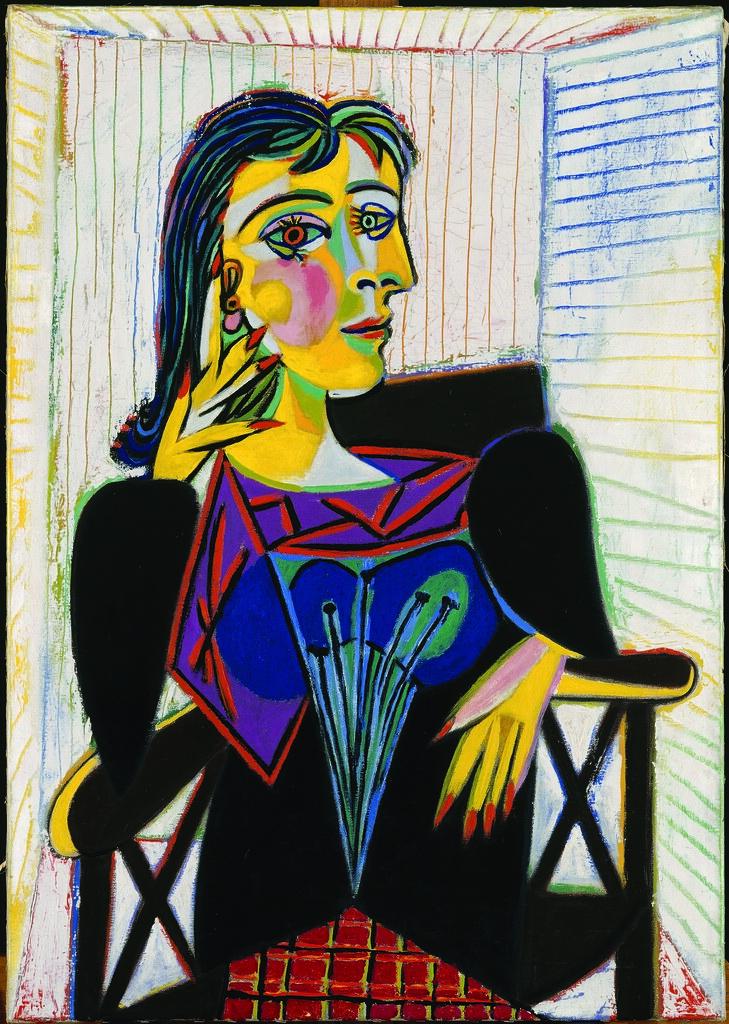

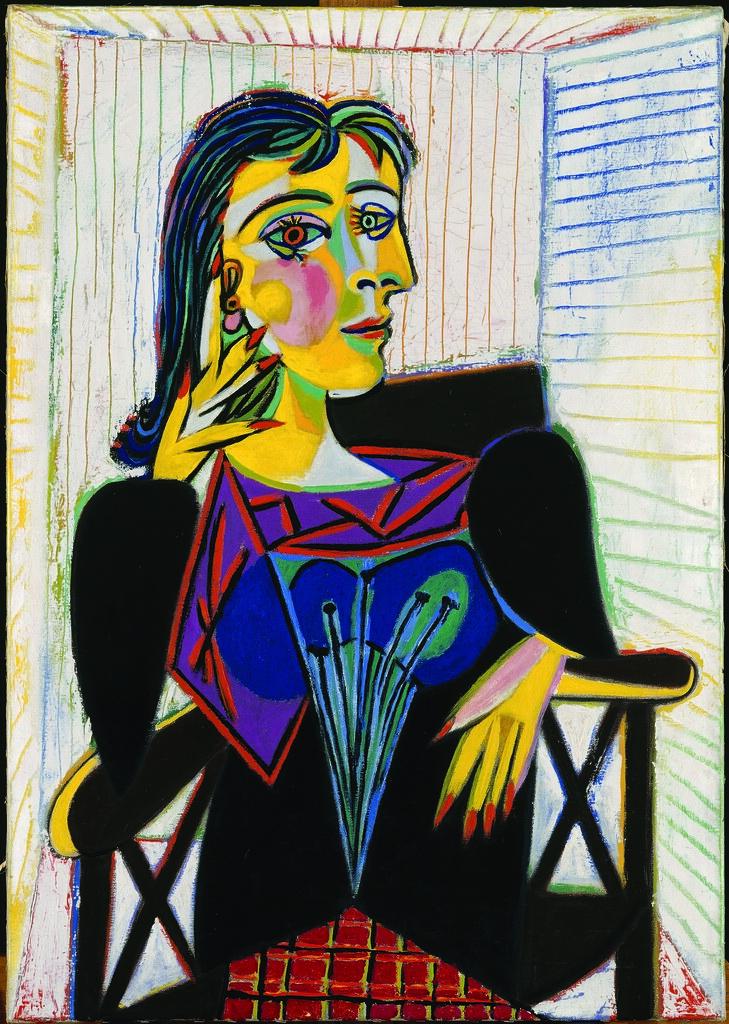

Dora Maar and The Weeping Woman

After Walter gave birth to their daughter Maya, and while Picasso was

still married to but separated from Khokhlova, he began a relationship

with the Surrealist photographer Dora Maar. Picasso’s new muse began to

appear frequently in his work, including the iconic painting

Portrait of Dora Maar (1937), on loan to the exhibition from the Musée national Picasso–Paris. The physiological elements in the painting, including sharp fingernails and coiffed black hair, also appear in one of Picasso’s most powerful graphic statements, the large-scale print

The Weeping Woman, I (1937).

Portrait of Dora Maar (1937), on loan to the exhibition from the Musée national Picasso–Paris. The physiological elements in the painting, including sharp fingernails and coiffed black hair, also appear in one of Picasso’s most powerful graphic statements, the large-scale print

The Weeping Woman, I (1937).

Picasso undertook a series of drawings, paintings, and prints depicting

the subject of the “weeping woman.” In the large-scale print, which was

printed by Lacourière, as in the two smaller manifestations of the

subject—

The Weeping Woman, III (1937)

and The Weeping Woman, IV (1937), printed by Jacques Frélaut (1913–1997)—the figure is distorted in a silent shriek of pain. The woman, who resembles Dora Maar, raises a scissor-like hand to wipe away the spiked tears that incise the overlapping planes of her contorted face.

The Weeping Woman, III (1937)

and The Weeping Woman, IV (1937), printed by Jacques Frélaut (1913–1997)—the figure is distorted in a silent shriek of pain. The woman, who resembles Dora Maar, raises a scissor-like hand to wipe away the spiked tears that incise the overlapping planes of her contorted face.

Françoise Gilot and Jacqueline Roque

In the 1940s Picasso became involved in politics, creating works

including

The Dove (1949)

for anti-war causes such as the First International Peace Conference.

By this time, his relationship with Maar had deteriorated and another muse, Françoise Gilot, had taken her place. The pair had two children, Claude and Paloma. In

Paloma and Her Doll on Black Background (1952) Picasso exercised a stylistic restraint reserved for his offspring whom, according to Gilot, he spent hours drawing and painting.

The Dove (1949)

for anti-war causes such as the First International Peace Conference.

By this time, his relationship with Maar had deteriorated and another muse, Françoise Gilot, had taken her place. The pair had two children, Claude and Paloma. In

Paloma and Her Doll on Black Background (1952) Picasso exercised a stylistic restraint reserved for his offspring whom, according to Gilot, he spent hours drawing and painting.

Two of Picasso’s last printed depictions of Gilot—

Woman at the Window (1952)

and The Egyptian Woman (1953)

—were large-scale tours de force, prints made with Lacourière using a newly invented process known as sugar-lift aquatint. The immediacy of the process, which allowed tonal areas to be directly painted on a plate, appealed to the impatient Picasso.

Woman at the Window (1952)

and The Egyptian Woman (1953)

—were large-scale tours de force, prints made with Lacourière using a newly invented process known as sugar-lift aquatint. The immediacy of the process, which allowed tonal areas to be directly painted on a plate, appealed to the impatient Picasso.

The final muse in Picasso’s life was his second wife and companion of

twenty years, Jacqueline Roque. He met Roque in the summer of 1952 while

she was working at the Madoura pottery works, during the same time that

his relationship with Gilot was falling apart.

Roque was a constant presence in his life and in his artistic production. Her dark hair, almond-shaped eyes, and aquiline nose are seen in the grisaille painting

Jacqueline Knitting (1954), which reveals her Mediterranean beauty. Jacqueline is depicted knitting, with her hands, body, hair, knitting needles, and yarn broken into crystalline forms. Her large hooded eye, high cheekbone, and nose are rendered in a more naturalistic manner.

Roque was a constant presence in his life and in his artistic production. Her dark hair, almond-shaped eyes, and aquiline nose are seen in the grisaille painting

Jacqueline Knitting (1954), which reveals her Mediterranean beauty. Jacqueline is depicted knitting, with her hands, body, hair, knitting needles, and yarn broken into crystalline forms. Her large hooded eye, high cheekbone, and nose are rendered in a more naturalistic manner.

Engaging with Old Masters

In the 1950s and 1960s Picasso frequently looked to the work of artists

who preceded him. His interpretations of Lucas Cranach, Rembrandt van

Rijn, Eugène Delacroix, and others number in the thousands. These

creative copies, or as Picasso called them, his “dialogues,” were made

in many media: paintings, prints, drawings, and sculpture. Picasso:

Encounters includes several examples of linoleum cuts created in

collaboration with printer Hidalgo Arnéra (1922–2007).

Picasso found the process of using different linoleum blocks for each

color cumbersome, so he collaborated with Arnéra to adopt a process

known as the reduction linocut. In this process Picasso successively cut

more and more away from one or two linoleum blocks. Arnéra printed

proofs of each color for Picasso to approve, and the printer then

created the final image. This reduction method required an extraordinary

feat of visualization. Picasso had to picture the final image with

precision, as each step was definitive and could not be changed or

reworked later.

Picasso: Encounters includes a series of four unpublished linocut trial

proofs modeled after Édouard Manet’s 1863 painting, Luncheon on the

Grass, offering a unique perspective on the artist’s and printer’s

process. The four proofs on view were eventually combined to create the

final linocut, which is also shown in the exhibition.

Picasso: Encounters is organized by the Clark Art Institute, with the

exceptional support of the Musée national Picasso–Paris.A 136-page, fully illustrated catalogue containing essays by exhibition curator Jay A. Clarke and Picasso expert Marilyn is distributed by the Clark and Yale University Press. This book features thirty-five of Picasso’s most important prints that showcase the artistic exchange vital to his process. It includes his first major etching from 1904, portraits of his lovers and family members, and prints that transform motifs by Rembrandt, Manet, and other earlier artists, such as an interpretation of Rembrandt’s Ecce Homo from 1970. Picasso | Encounters considers the artist’s major statements in printmaking throughout his career.